Sundown town facts for kids

Sundown towns, also called sunset towns or gray towns, were places in the United States where only white people were allowed to live. These towns used special rules, threats, or even violence to keep non-white people out. They were most common before the 1950s. The name "sundown town" came from signs that told "colored people" to leave town before sundown.

Similar rules also created sundown counties and sundown suburbs. After the civil rights movement ended in 1968, the number of sundown towns went down. However, some people say that certain practices today still act like a modern version of these towns.

It's important to know that sundown towns were different from towns that just happened to have no Black residents for other reasons. Sundown towns actively kept non-white people away. We know about these towns from old newspaper stories, local histories, and government records. These records often show that Black people were either completely absent or their numbers dropped sharply in these towns.

Contents

History of Sundown Towns

The idea of limiting where African Americans and other minority groups could go at night started a long time ago, even during America's colonial period. For example, in 1714, the area of New Hampshire passed a law that said:

No Indian, Negro, or Molatto is to be from Home after 9 o'clock.

This law was meant to stop "disorders" at night.

After the American Revolution, the state of Virginia was the first to stop all Free Negros (Black people who were not enslaved) from entering the state. Laws that limited where Black people could live were inspired by old English laws. These English laws tried to control where poor people could go. American officials used similar ideas to stop Black Americans from settling in their communities.

After the Reconstruction era ended, many towns and counties across the U.S. became sundown places. This was part of the Jim Crow laws and other rules that kept people separated by race. Often, it was official town policy or real estate agents used special agreements to control who could buy or rent homes. Sometimes, people were scared away through threats or harassment by police. Even though official sundown towns don't exist today, some still use the term for towns that practice other kinds of racial exclusion.

In 1844, Oregon, which had already banned slavery, also banned African Americans from the territory. If Black people didn't leave, they could be punished. While no one was actually whipped under this law, it showed how serious the ban was. Other laws against Black Americans entering Oregon were passed later and weren't removed until 1926.

Other places also used laws to stop Black people from living in their cities, towns, and states. In 1853, Illinois banned new Black residents. If new residents stayed more than ten days and couldn't pay a fine, they were forced to work. This law was very unpopular but wasn't removed until the end of the Civil War in 1865. Similar bans on Black migration were passed in Michigan, Ohio, and Iowa.

New laws continued into the 1900s. In 1911, the mayor of Louisville, Kentucky, suggested a law to stop Black people from owning property in certain parts of the city. This law was challenged in the U.S. Supreme Court in 1917. The Court decided that such laws were against the Constitution. This meant similar laws could not be passed in the future. However, this didn't stop towns from keeping Black residents out. Some city planners and real estate companies used their private power to keep neighborhoods segregated. Besides unfair housing rules, violence and harassment were sometimes used to make sure Black people left cities after sundown. White people in the North felt threatened by more minority groups moving into their neighborhoods, and racial tensions grew. Violence between races became more common, sometimes leading to race riots.

After the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, especially after the Fair Housing Act of 1968 made it illegal to treat people differently based on race when selling or renting homes, sundown towns slowly disappeared. Some unofficial sundown towns still existed into the 1980s. It's hard to know exactly how many sundown towns there were because most didn't keep records of their rules or signs. However, hundreds of cities in America were sundown towns at some point.

Being a sundown town meant more than just Black Americans not being able to live there. Any Black people found in these towns after sunset could face harassment, threats, and violence.

The U.S. Supreme Court case of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 said that separating schools by race was unconstitutional. This decision might have caused some towns in the South to become sundown towns. For example, Missouri, Tennessee, and Kentucky saw big drops in their African-American populations after this decision.

Today, most sundown towns are a thing of the past. However, some historians note that even after towns started to allow different races, the effects of their past segregation can still be seen.

How Sundown Towns Worked

Excluding Different Groups

African Americans were not the only group kept out of white towns. For example, in 1870, Chinese people made up one-third of Idaho's population. But after violence and an anti-Chinese meeting in Boise in 1886, almost no Chinese people remained by 1910.

The towns of Minden and Gardnerville in Nevada had a rule from 1917 to 1974 that made Native Americans leave the towns by 6:30 p.m. every day. A whistle, and later a siren, would sound at 6 p.m. to tell Native Americans to leave by sundown. In 2021, Nevada passed a law against using Native American images as school mascots and against sirens linked to sundown rules. Even so, Minden kept playing its siren for two more years, saying it was a tribute to first responders. Another state law in 2023 finally made Minden stop the siren.

In Nevada, the ban was also expanded to include Japanese Americans.

Some road signs from the early 1900s showed these rules:

- In Colorado: "No Mexicans After Night"

- In Connecticut: "Whites Only Within City Limits After Dark"

Some experts today worry that new immigration laws in certain towns could create similar situations for non-Black people, especially Hispanic Americans, even if the laws are meant for undocumented immigrants.

From 1851 to at least 1876, Antioch, California, had a sundown rule that stopped Chinese residents from being out in public after dark. In 1876, white residents forced the Chinese out of town and then burned down the Chinatown part of the city.

Chinese Americans were also kept out of most of San Francisco, which led to the creation of Chinatown.

Travel Guides for Safety

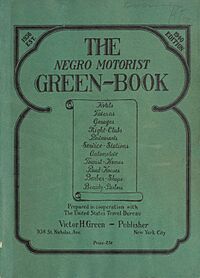

The Negro Motorist Green Book, often just called the "Green Book," was a special guide for African American drivers. It was published every year from 1936 to 1966, during the Jim Crow era when unfair treatment against non-white people was common. An important civil rights leader, Julian Bond, called it "one of the survival tools of segregated life."

Road trips for African Americans were difficult and sometimes dangerous because of racial separation, police stopping them for no reason, and the risk of disappearing in sundown towns. There were at least 10,000 sundown towns in the U.S. as late as the 1960s. In these towns, non-white people had to leave by dusk, or they could be arrested by police or face worse dangers. These towns were not just in the South; they were all over the country, including places like Levittown, New York, and Glendale, California. The Green Book even suggested that Black drivers wear a chauffeur's cap and, if stopped, say they were delivering a car for a white person.

In 2017, the NAACP, a civil rights organization, warned African-American travelers about visiting Missouri. This was the first time the NAACP issued a warning for an entire state. The NAACP president suggested that if Black travelers had to go to Missouri, they should carry bail money with them.

Sundown Suburbs

Many suburban areas in the United States were created after Jim Crow laws were put in place. Most suburbs were made up of only white residents from the very beginning. Most sundown suburbs were created between 1906 and 1968. By 1970, during the height of the Civil Rights era, some sundown suburbs had started to allow different races. However, harassment and other methods were used to keep African Americans out of new suburban areas.

List of Sundown Towns

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |