Oregon black exclusion laws facts for kids

The Oregon black exclusion laws were rules and laws made in the Oregon Country and later the state of Oregon. These laws tried to stop Black people from living or settling in Oregon. The first law started in 1844. It said that any Black person who stayed in the area could be whipped if they didn't leave. More laws were passed in 1849 and 1857. The last of these laws was finally removed in 1926. These laws came from beliefs that were against both slavery and Black people. People sometimes said they were needed because they feared Black people might cause Native American groups to rise up.

Contents

Oregon's Early Exclusion Laws

Many early white settlers in the Oregon Country were against slavery but also did not want Black people living near them. Many came from states like Missouri that had similar laws. These settlers thought banning slavery would avoid political problems. But they also worried that communities of freed slaves would compete with white people for power. One early settler wrote that many pioneers "hated slavery, but a much larger number of them hated free negroes worse even than slaves."

In 1843, the Provisional Government of Oregon created its first laws, which included banning slavery. However, it wasn't clear how this ban would be enforced. On June 26, 1844, the first Black Exclusion Law was passed. It repeated the ban on slavery in Oregon. It also forced Black and mixed-race settlers to leave Oregon within a few years. If they didn't, they could face severe physical punishment. This part of the law was changed in December 1844. The new rule allowed a freed slave to be temporarily sold again. But the owner had to agree to remove them from the territory later. This meant slavery was allowed for a short time. This law was removed in 1845, and no one was ever punished under it.

On September 21, 1849, the Oregon Territory passed its second exclusion law. This law said that no "negro or mulatto" could enter or live in Oregon unless they were already there. At least four Black people were punished under this law. One was Jacob Vanderpool, a sailor. Three others were later allowed to stay.

A census in 1850 showed fewer than 50 Black people living in Oregon. This included George Washington Bush, a mixed-race man from Pennsylvania. He was forced to move north of the Columbia River after the first exclusion law. George Washington, another free Black man, founded the town of Centralia, Washington.

In 1852, Robin Holmes, a Black slave, took his owner, Nathaniel Ford, to court. Holmes argued that he and his family were being held illegally. The case, Holmes v. Ford, went to the territorial Supreme Court. In June 1853, Judge George Henry Williams ruled that slavery was illegal in Oregon. Holmes's family later said that Ford had actually encouraged the lawsuit to help end slavery in the state.

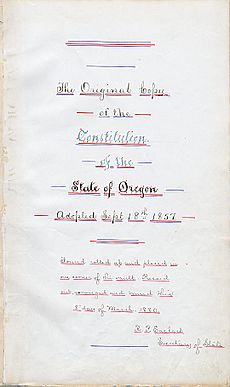

On November 7, 1857, Oregon's leaders met to write the state's Constitution. They suggested two main ideas: to allow slavery and to ban Black people from the state. This ban would also stop Black people from signing contracts or owning land. The idea to allow slavery failed. But the exclusion law passed. Oregon was the only state to join the United States with such a law. There are no records that this 1857 law was ever enforced. In 1865, the state legislature voted against a new law that would have allowed sheriffs to deport Black residents.

The 1844 Law and Its Changes

The Cockstock incident was a big reason the first Black exclusion law was passed. This event involved a fight between a Wasco Native American man named Cockstock and a free Black man named James D. Saules. They were arguing over a horse. The argument turned into a violent clash that killed three men. This led white settlers to fear that Black people could cause Native American tribes to rise up against them.

On June 24, 1844, just days after the Cockstock Incident, the Oregon Provisional Legislature quickly passed a bill. Peter Burnett proposed this bill "for the prevention of slavery." The bill was voted into law the next day. It included ways to enforce the ban on slavery, which was already in place. These laws also set a time limit for all free Black people to leave the territory. Free Black men had two years, and free Black women had three years. The first version of the law suggested a harsh punishment for those who didn't leave. This part was changed in December 1844. A week after the law passed, Burnett wrote that the bill was meant to "keep clear of that most troublesome class of population."

Years later, Burnett said the Exclusion Law was meant to keep Black people, who had no political power, from being around white people who did. He thought this would remind Black people of their "inferiority." He also suggested that their presence was "injurious to the dominant class itself." This meant he thought it was bad for white people because it might tempt them to be unfair. In his book, History of Oregon, William H. Gray called the law "inhuman." Burnett argued that Gray did not describe the law correctly.

We don't know exactly how this law affected Black people in Oregon. There are no records that it was ever directly enforced. However, the threat of this law made an African-American settler named George W. Bush and his group, the Bush-Simmons party, change their plans. They arrived shortly after the law was passed. They decided to create a new path of the Oregon Trail. They went north across the Columbia River into land controlled by the British. There, they started the first U.S. settlement on the Puget Sound, in what is now Washington State. Later, the U.S. Congress passed a special law to confirm Bush's right to his land. This was because people worried the Exclusion Law might apply to lands in Washington before it became a separate territory.

The 1844 law said that slavery was banned in Oregon. But it also said that if slave owners brought slaves into Oregon, they had three years to remove them. If they didn't, the slaves would become free. The law also stated that free Black or mixed-race people had to leave Oregon within two years for men and three years for women. If they didn't leave, they could be arrested and face severe physical punishment. If they still didn't leave after that, they would be punished again every six months until they left.

In December 1844, the law was changed. The parts about physical punishment were removed. Instead, if a free Black or mixed-race person didn't leave, they could be arrested. Then, they would be publicly hired out for a short time. The person who hired them had to promise to remove them from Oregon within six months after their work ended.

The 1849 Law

In September 1849, the legislature passed another exclusion law. It stated that it was "highly dangerous to allow free negroes and mulattos to reside in the Territory." It also claimed they might "intermix with the Indians, instilling in their minds feelings of hostility against the white race." The 1849 law ordered any Black people entering the territory to leave within 40 days. In 1851, this law was used against Jacob Vanderpool, a man from the West Indies who had moved to Oregon City. A white resident brought a case against Vanderpool. He was arrested and ordered to leave Oregon within 30 days.

The family of Abner Hunt Francis was also ordered to leave the state within 40 days. But they were allowed to stay after 225 citizens signed a petition. This petition led to an attempt to change the exclusion law to allow Black settlers to stay if they promised good behavior. This attempt failed. The Francis family moved to Canada in 1861. A petition was also used in 1854 to stop Morris Thomas and Jane Snowden from being deported.

Samuel Thurston, Oregon's representative in Congress, explained the law to Congress. He said that Black people "associate with the Indians and intermarry." He feared that if they were allowed to enter freely, a "mixed race would ensue inimical to the whites." He believed that if Native Americans were led by Black people, who knew more about white customs and language, they would become "much more formidable." He warned that "long and bloody wars would be the fruits of the commingling of the races." This law was removed in 1854.

The 1857 Law

In 1857, after Oregon voters chose to become a state, they held a meeting to write their constitution. The new constitution had 185 sections. Most of these sections (172) were taken from other state constitutions. The new parts mainly dealt with racial exclusion or money matters. The constitution included an Exclusion Law in Section 35 of Oregon's Bill of Rights. This section stated:

"No free negro or mulatto not residing in this state at the time of the adoption of this constitution, shall come, reside or be within this state or hold any real estate, or make any contracts, or maintain any suit therein." It also said the state legislature must create laws to remove such Black and mixed-race people from the state. It also said there would be punishment for anyone who brought them into the state, hired them, or gave them shelter.

John R. McBride, who later became a state senator, described this change. He said it was "largely an expression against any mingling of the white with any of the other races." He added that since there weren't many other races in Oregon yet, people believed they should not encourage them to come. He said they were building a new state and wanted to encourage "only the best elements to come to us, and discourage others."

The question of slavery itself was put to a public vote. People voted against slavery (7,727 to 2,645). But they voted in favor of the racial exclusion policies (8,640 to 1,081). The final constitution stopped "negroes, mulattos and Chinamen" from voting or owning land in the state.

Repeal of the Laws

Oregon's state constitutional amendment, Section 35, was made legally invalid after the Civil War. This happened when the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was approved in 1868. However, Section 35 officially remained in the state's constitution for another 58 years. In 1925, the Oregon legislature suggested formally removing Section 35. This idea was put to Oregon voters in 1926. They approved it with 62.5% of the votes.

Later, in 2002, Measure 14 was approved by voters (71% to 29%). This measure removed any remaining mentions of the 1857 referendum from the constitution.

Legacy of the Laws

From 1850 to 1860, Oregon's Black population grew by only 75 people. In comparison, neighboring California's Black population grew by 4,000 during the same time. Oregon's Black exclusion laws are linked to the state having a lower-than-average Black population, even today (around two percent). Historian Cheryl Brooks has suggested that Oregon's small Black population has made it harder for people in Oregon to see and understand problems with racial discrimination in the state.

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |