Peter Hardeman Burnett facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Peter Hardeman Burnett

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 1st Governor of California | |

| In office December 20, 1849 – January 9, 1851 |

|

| Lieutenant | John McDougall |

| Preceded by | Bennet C. Riley (as military governor) |

| Succeeded by | John McDougall |

| 5th Supreme Judge of the Provisional Government of Oregon | |

| In office September 6, 1845 – December 29, 1846 |

|

| Preceded by | James Nesmith |

| Succeeded by | Jesse Quinn Thornton |

| Associate Justice of the California Supreme Court | |

| In office January 13, 1857 – October 12, 1857 |

|

| Appointed by | Governor J. Neely Johnson |

| Preceded by | Solomon Heydenfeldt |

| Succeeded by | Stephen J. Field |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 15, 1807 Nashville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | May 17, 1895 (aged 87) San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Santa Clara Mission Cemetery |

| Political party | Independent |

| Spouse |

Harriet Rogers

(m. 1828; died 1879) |

| Children | 6 |

| Signature | |

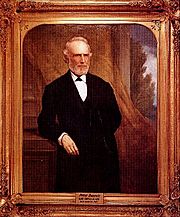

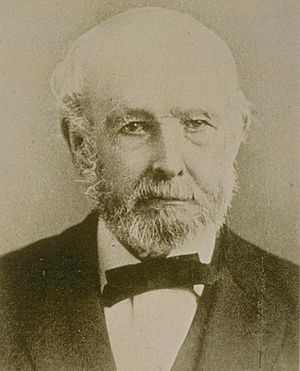

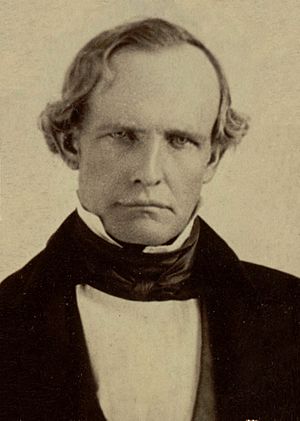

Peter Hardeman Burnett (November 15, 1807 – May 17, 1895) was an American politician. He served as the first elected Governor of California from December 20, 1849, to January 9, 1851. Burnett became Governor almost a year before California officially joined the United States as the 31st state in September 1850.

Burnett grew up in Missouri in a family that owned enslaved people. He moved west after facing money problems in his business career. First, he lived in Oregon Country, where he became a judge for the local government. While in Oregon, he supported laws to keep African Americans out of the territory. He even wrote a law that allowed for the whipping of any free Black people who refused to leave Oregon. This law was seen as too harsh and was never put into action. Voters later removed it in 1845.

In 1848, Burnett moved to California during the exciting time of the California Gold Rush. He restarted his political career and became a judge on the Supreme Court of California. In this role, he was involved in a case that sent a formerly enslaved man back to Mississippi. Even though Burnett had owned enslaved people himself, he did not want California to become a state where slavery was allowed. Instead, he pushed for laws to keep all African Americans out of California.

As Governor, Burnett signed a law called the "Act for the Government and Protection of Indians." This law allowed for the forced labor of Native Californians and played a part in their terrible treatment. In 1851, he said that a "war of extermination" would continue until the "Indian race becomes extinct." He also fought against efforts by federal leaders to protect some Native land rights. Burnett also supported keeping Chinese immigrant workers out of California. After his time as governor, he continued to support the federal Chinese Exclusion Act.

Contents

Early Life and Moving West

Peter Burnett was born in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1807. He grew up in rural Missouri. His family owned enslaved people, and he later owned two himself. In 1828, he married Harriet Rogers.

Burnett did not go to a formal school beyond elementary grades. However, he taught himself about law and government. After running a general store, he started a career in law. He once defended a group of Mormons who were accused of serious crimes. Burnett asked for their trial to be moved to a different place. While they were being moved, the people he was defending escaped.

Politics in Oregon

In 1843, Burnett was deep in debt from his business failures. He decided to move his family from Missouri to Oregon Country (which is now Oregon). He hoped to become a farmer there to pay off his debts, but this plan did not work out.

While in Oregon Country, Burnett started his political journey. He was elected to the provisional legislature from 1844 to 1848. In 1844, he helped build Germantown Road, which connected the Tualatin Valley to what is now Portland, Oregon. During his time in Oregon, Burnett, who was a Protestant, began to explore new religious ideas. By 1846, he and his family became Catholic.

While in the Oregon Legislature and later as a judge, Burnett supported Oregon's first laws to exclude Black people. In 1844, a law was passed that said slave owners could keep their enslaved people for up to three years. After that, all Black people, whether free or enslaved, had to leave Oregon Country or face being whipped. This harsh law was never put into practice.

Moving to California

When gold was discovered in Coloma, California, on January 24, 1848, Burnett and his family moved south. They wanted to join the California Gold Rush. After finding some gold, Burnett decided to pursue a law career in San Francisco. This city was growing very fast because of the Gold Rush.

On his way to the Bay Area, Burnett met John Augustus Sutter, Jr. He was the son of a famous Swiss pioneer, John Sutter. The younger Sutter offered Burnett a job selling land plots for the new town of Sacramento. Over the next year, Burnett made almost $50,000 selling land in Sacramento. This city was perfectly located near the Sierra Nevada mountains and the Sacramento River, which large ships could use.

In 1848, Burnett also helped found the city of Oregon City, California in Butte County, California.

Becoming Governor of California

In 1849, Burnett decided to return to politics. That year, the first California Constitutional Convention was held in Monterey, California. There, politicians wrote documents to help California become a state in the United States. During the vote to approve the California Constitution in 1849, Burnett decided to run for the new territory's first civilian governor. He was well-known in Sacramento and San Francisco and had experience in the Oregon government.

Burnett easily won the election against four other candidates, including John Sutter. He was sworn in as California's first elected civilian governor on December 20, 1849. The ceremony took place in San Jose, California, in front of what would soon become the California State Legislature.

Burnett's Time as Governor

In the first days of Burnett's time as governor, he and the California Legislature worked to create a state government. They set up state offices, departments, and divided the state into 27 counties. They also chose John C. Frémont and William M. Gwin as California's senators to the federal U.S. Senate.

Even though California leaders acted like it was already a state, the U.S. Congress and President Zachary Taylor had not yet officially approved statehood. This was partly because California was far away from the rest of the U.S. at the time. It was also because politicians and the public were very eager for California to join the Union quickly. After many debates in the U.S. Senate, California was finally admitted as a non-slavery state on September 9, 1850. This was part of a larger agreement called the Compromise of 1850. Californians did not find out about their official statehood until a month later. On October 18, the ship Oregon arrived in San Francisco Bay with a banner that read "California Is a State."

During these steps toward statehood, Burnett's popularity dropped. His relationships with the Legislature, the press, and the public became difficult. In early 1850, the Legislature passed bills to make Sacramento and Los Angeles official cities. Burnett vetoed both bills, saying that special city bills were against the constitution. He believed that county courts should handle city approvals. The Legislature failed to overturn his veto for Los Angeles but succeeded for Sacramento, making it California's first official city.

For California's legal system, Burnett suggested a mix of different laws. He wanted to combine parts of civil law (based on written codes) and common law (based on court decisions). He suggested using parts of Louisiana's civil laws and adopting American common law for crimes, evidence, and business. This caused a big debate among lawyers in California. Most wanted common law, while a few wanted civil law. In February 1850, a committee recommended adopting common law. Burnett signed this bill into law on April 13, 1850.

Burnett was seen as a distant politician who had little support from the Legislature and the press. He became frustrated as his plans stopped moving forward, and his way of governing was often criticized. Newspapers and lawmakers often made fun of him. After just over a year in office, Burnett, the first governor of California, became the first to resign. He announced his resignation in January 1851, saying it was for personal reasons. Lieutenant Governor John McDougall took over as Governor of California on January 9.

His Policies

Just like in Oregon, Burnett pushed for laws to keep Black people out of California. This angered people who wanted to bring the Southern system of slavery to the West Coast. However, his ideas were not approved by the Legislature.

Burnett also pushed for high taxes on immigrants from other countries. In 1850, he signed the Foreign Miners Tax Act. This law made every miner who was not from America pay $20. Burnett also strongly argued for more taxes and for using the death penalty for theft.

Burnett also tried to remove Native Americans and foreign miners from California. In 1851, federal leaders tried to make treaties with Native tribes in California. However, Governor Burnett blocked these treaties. He thought they were too generous in giving land to the tribes. Instead, because of the desire for gold, Burnett said that "a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct." He believed this was unavoidable.

After Being Governor

One year after leaving the governorship, Burnett was finally able to pay off the large debts he had from Missouri almost twenty years earlier. He took on several different jobs. He served briefly as a judge in the California Supreme Court from 1857 to 1858. He was also a member of the Sacramento City Council and worked as a lawyer in San Jose. He became a well-known supporter of Catholicism during the Victorian period. Later, he became the president of the Pacific Bank of San Francisco.

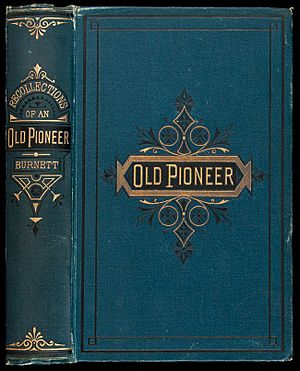

Although he did not get involved in politics much after the 1860s, Burnett strongly supported the federal Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. In 1880, he published his autobiography, called Recollections and Opinions of an Old Pioneer. He passed away on May 17, 1895, at the age of 87 in San Francisco. He is buried in the Santa Clara Mission Cemetery in Santa Clara, California.

Legacy

Peter Burnett's legacy is seen in a mixed way today. He is considered one of the founders of modern California in its early days. However, his racist views towards Black, Chinese, and Native American people have damaged his reputation.

Burnett's time in the Oregon Provisional Legislature helped lead to the exclusion of Black people from that state until 1926. In 1844, one of his ideas in Oregon was to force free Black people to leave the state. If they stayed, they could be whipped. This was called "Burnett's lash law." It was considered "unduly harsh" and was never put into action. Voters removed it in 1845.

His open dislike for foreign workers also influenced many state and federal lawmakers in California. This led to future laws that were against immigrants, like the Chinese Exclusion Act, which was passed 30 years after he left the governorship. Burnett also openly supported getting rid of local California Indian tribes. This policy continued with later state governments for several decades. They even offered money for proof of dead Native Americans.

San Francisco's Burnett Avenue, near the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood, is named after him.

The Burnett Child Development Center, a preschool in a mostly Black San Francisco neighborhood, was named after Burnett. However, when his racist views were rediscovered, the school was renamed in 2011. It is now called the Leola M. Havard Early Education School, honoring San Francisco's first African-American principal.

Similarly, the Peter H. Burnett Elementary School in Long Beach was recently renamed because of Burnett's views. It is now named after Bobbi Smith, the first African-American member of the Long Beach Unified School District's board.

In 2019, Peter Burnett Middle School in San Jose, California was renamed Muwekma Ohlone Middle School. This name honors the original inhabitants of that area.

In July 2020, Peter Burnett Elementary School in Hawthorne, California was renamed to 138th Street Elementary School.

See also

In Spanish: Peter Burnett para niños

In Spanish: Peter Burnett para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |