1964 Monson Motor Lodge protests facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 1964 Monson Motor Lodge protest |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of St. Augustine movement in the Civil Rights Movement |

|||

James Brock pouring acid into his pool

|

|||

| Date | June 18, 1964 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

|

||

| Goals | Desegregation | ||

| Resulted in |

|

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

The 1964 Monson Motor Lodge protest was a key event during the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. It happened on June 18, 1964, at the Monson Motor Lodge in St. Augustine, Florida. Leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Hosea Williams organized protests in St. Augustine. They chose this city because it had strong racial segregation but also relied on money from northern tourists. The city was also about to celebrate its 400th anniversary, which would bring more attention to the protests.

During this time, the Civil Rights Bill was being debated in the U.S. Senate. On June 10, the debate ended, making the bill's passage likely. The next day, Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested in St. Augustine. He tried to eat lunch at the Monson Motor Lodge, but the owner, James Brock, refused to serve him. King was jailed for trespassing. From jail, he asked Rabbi Israel Dresner to bring other rabbis to St. Augustine to help.

On June 18, 17 rabbis were arrested at the Monson, the largest group of rabbis ever arrested in American history. At the same time, black and white activists jumped into the Monson's swimming pool to protest. James Brock, the owner, poured muriatic acid into the pool. This was a cleaning fluid, but it looked like he was trying to harm the protesters. Photos of this, and of a policeman jumping into the pool to arrest them, became famous worldwide.

Even after the Civil Rights Act passed, many businesses in St. Augustine were slow to end segregation. Courts eventually forced Brock to integrate his businesses. Soon after, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), who were against desegregation, firebombed the Monson. The judge felt Brock had brought this violence on himself by supporting segregation earlier.

On June 30, Florida Governor Farris Bryant created a committee to help improve race relations in St. Augustine. Brock struggled to get bank loans for the damage and declared bankruptcy the next year. In 1965, St. Augustine celebrated its 400th anniversary, but racial tension remained. Tourism was badly hurt, costing the city millions of dollars.

Contents

- How the Protests Started

- The Protest at the Monson

- What Happened Next

- Brock's Reaction

- Official Reactions

- Beach Protest

- Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Desegregation in St. Augustine

- Segregationist Protests at Monson

- Re-segregation of the Monson Motor Lodge

- Legal Hearings

- Dr. King Visits St. Augustine Again

- Segregationist Backlash

- Tourism Downturn

- Racial Tensions

- Brock's Bankruptcy

- Official Report

- What Happened Later

- In Photographs and Film

How the Protests Started

Planning the Campaign

The protests in St. Augustine began on Easter Sunday, March 29, 1964. They specifically targeted the city's food and tourism businesses. These businesses were chosen because they showed how much race and social class mattered in the city. The Monson Motor Lodge was a main target. It was a "big posh lily white" motel. The owner, James Brock, was a well-known local businessman. Reporters often stayed at the Monson, making it easy to get media attention.

An interracial group, including the 72-year-old mother of Massachusetts' Governor, tried to enter the motel's restaurant. They were arrested, and the news made headlines across the country. The mayor called the protesters "scalawags" from the north. This arrest brought national attention to St. Augustine's racial issues. Soon, leaders from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) arrived. They started workshops on non-violent protest.

The SCLC focused on local businesses like the Monson. They hoped to put financial pressure on them to end segregation. By the end of May, the motel faced almost daily sit-ins. Martin Luther King Jr. and the SCLC learned from past protests that strong images of black and white protesters facing white supremacists moved the nation. To increase pressure, they started "wade-ins" to integrate public pools and beaches. In response, many Ku Klux Klan (KKK) members came to St. Augustine. There were clashes day and night.

Sit-in Protest at Monson

King arrived in St. Augustine on May 31 and stayed in Lincolnville, a black community near the Monson Motor Lodge. King wanted to be arrested to make the struggle more intense. He planned to take part in a sit-in at the Monson's restaurant. On June 11, King and his colleagues arrived at the Monson for lunch. The SCLC had told the press, so many reporters were there.

The motel manager, James Brock, met them. He told them they were on private property. Brock tried to speak privately with King, but microphones were pushed between them. News reporters crowded around. Brock told King that the restaurant did not serve black people. King said they would wait until it did, and some of his group began a sit-in. Their conversation was polite at first. Brock said he would only allow them in with a federal court order or if local businessmen agreed.

Their discussion lasted about 15 minutes. It was described as having a "carnival atmosphere." Brock eventually asked King and his group to leave. King, however, intended to be arrested. Brock became angry, asking King to take his "nonviolent army somewhere else." King replied, "we'll wait in the hope that the conscience of someone will be aroused." Brock told reporters that the only black people allowed were servants of white guests, who could eat in the service area. King asked Brock if he understood the "humiliation our people go through." Brock, in turn, asked King to understand his position as a respected businessman. He announced, "We expect to remain segregated."

Activists Arrested

Brock became very frustrated and called the police. The police chief and sheriff arrived with arrest warrants for King and his colleagues. King and his companions were arrested under Florida's "unwanted guest" law. They refused to pay bail, so they were jailed in the crowded St. John's County Jail. Because of fears for his safety, King was moved to Jacksonville.

Civil Rights Bill Debates

At the same time, the Civil Rights Bill was being debated in the Senate. King's arrest brought more attention to the bill. The debate had lasted 75 days. On the same night King was arrested, the Senate voted to end the debate. This was the first time the Senate had stopped a debate on civil rights. The bill's passage was now almost certain. Some believed that if white people in St. Augustine had not reacted violently, the protests might have ended. But the SCLC often provoked white racists to draw attention.

King's Release and Tensions

King was released from jail the next day. He looked tired and scared. He left St. Augustine immediately, going to Harvard University and then to Washington, D.C. King made sure the nation focused on the KKK's actions and St. Augustine officials' strong stand against protests. Klan demonstrations continued for several days.

The same day King was released, city business leaders met at the Monson. They suggested creating a committee to study racial tensions. This committee was first planned to have no black members, but this was changed. The mayor, however, refused, seeing it as giving in to the SCLC. The committee was not meant to negotiate with King or other SCLC leaders.

City authorities offered to set up a committee with five black and five white members. This committee would investigate segregation complaints if protests and meetings ended. The SCLC supported this as a fair compromise. A secret meeting of St. Augustine businessmen also approved the new committee. A Grand Jury was expected to decide on this issue soon.

Protest Meetings

On June 17, Rabbi Albert Vorspan and 16 other rabbis from different states joined a meeting at the St. Augustine Baptist Church. King announced their arrival to an excited crowd. Rabbi Dresner, who had experience with such meetings, spoke to the crowd. The rabbis then marched with Fred Shuttlesworth, Andrew Young, and 300 others to the old St. Augustine Slave Market. This market was a key symbol of protest in the city.

King used night marches to create "creative tension" and get national attention. The Sheriff told leaders that no permits would be given for more marches. The SCLC had created the tension they needed.

The Protest at the Monson

Protesters Enter the Motel

Shuttlesworth and C. T. Vivian led about 50 supporters to the Monson Motor Lodge around 12:40 p.m. King watched from a park across the street. Again, Brock met the integrated group and said his business was segregated. By now, the daily protests and pressure from segregationists had made Brock irritable. He had also received death threats. Brock locked the doors when the group arrived.

Jewish Prayers

To distract the motel staff, Rabbi Israel Dresner led 15 other rabbis in an open-air Hebrew prayer meeting in the parking lot. The rabbis asked Brock to let them eat in his restaurant, but he refused. Brock, a Baptist deacon, seemed to lose his temper when the rabbis knelt to pray for him in his car park. Police were already there. Brock pushed each kneeling rabbi towards the police to be arrested.

Protesters Enter the Pool

Meanwhile, SCLC activists Al Lingo and J. T. Johnson led a group to integrate the swimming pool. The press had been told about this plan. Seven minutes after the rabbis arrived, shouts came from the pool. Young black and white people were swimming together. Two white activists, who were guests, said they had invited friends to use the pool.

Brock's Actions Against Protesters

News cameras started filming. Brock told the white swimmers, "you're not putting these people in my pool." He went to his office and brought out a large drum of muriatic acid. He poured it into the pool, yelling that he would "burn them out." This was a cleaning fluid, and the threat was mostly harmless, but it looked very dramatic. Brock also yelled that he was "cleaning the pool," implying it was now "racially contaminated." One report even said he let an alligator into the pool.

Crowds and Dr. King's Arrival

As the swimmers tried to leave the pool, the crowd shouted threats. Police held the crowd back. Brock seemed to lose control, weeping and shouting, "I can't stand it." King and his group approached the motel but were surrounded by hecklers. Hosea Williams later said he feared being thrown into the pool, as he couldn't swim.

Arrest of Protesters

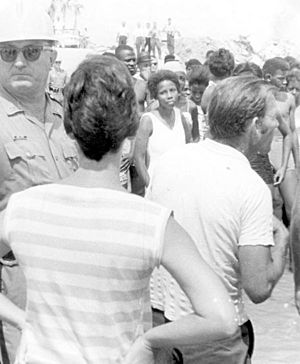

Brock's attempt to force the protesters out didn't work. An officer, James Hewitt, announced that all the swimmers were under arrest. An off-duty policeman, Officer Henry Billitz, jumped into the pool fully clothed (except for his shoes) to drag them out. He also hit them. A state attorney later heard a "near riot" from his office near the motel. Over 100 people were watching by the poolside. This new tactic had a big impact. It also made the St. Augustine business community even more against the protests. White people were told this was what would happen if black people gained more rights.

Three days before the pool integration, Governor Farris Bryant ordered state officers to handle arrests during riots. However, local officers were also present. One local deputy hit an arrested swimmer as he was being taken from the pool to a police car. The swimmers, still wet, were arrested for trespassing.

The arrest of Rabbi Dresner and his colleagues was the largest number of rabbis ever arrested at one time. While in prison, the rabbis wrote a document called "Common Testament." After their arrests, a wave of anti-Jewish feelings spread through St. Augustine.

What Happened Next

Brock's Reaction

Brock was very angry and felt betrayed. He drained and refilled his pool to "purify" it after the integration. He also hired armed guards for the pool and raised the Confederate flag above the motel. This event is considered one of the most important in the St. Augustine Civil Rights Movement. Business leaders withdrew their support for the biracial committee. They were worried that King intended to "put the Monson out of business." Brock's entire business depended on the Monson, and protests threatened his profits.

Official Reactions

Two days after the pool integration, Governor Bryant banned public demonstrations, but the violence continued. The all-white grand jury called witnesses to the Monson integration. Instead of approving the biracial committee, they issued a new report. They claimed St. Augustine had "harmonious race relations" and "non-discrimination in governmental affairs."

The jury attacked King and the SCLC. They asked if the SCLC truly wanted St. Augustine's problems solved. If so, they told King and others to leave the community for 30 days. If they did, the jury said it would confirm the biracial commission. However, all its white members resigned, and the commission never met. The Governor had only intended the commission to help solve the crisis quickly. The Monson motel integration had a major impact on the jury's decision.

Beach Protest

The same protest strategy was used less than a week later. SCLC activists did a "wade-in" at the whites-only St. Augustine beach. This time, violence broke out as segregationists attacked the protesters. Many arrests were made by Florida Highway Patrol officers. Armed groups of both black and white people drove around at night, shooting at cars and windows.

Civil Rights Act of 1964

On July 2, 1964, the Civil Rights Act became a United States Federal law. This law made discrimination illegal in hotels, restaurants, theaters, and other public places. It also banned job discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. The law stopped federal funding for programs that discriminated.

The Civil Rights Act passed the Senate the day after the Monson Motel swim-in. Some argue that the St. Augustine protests directly helped the act pass. However, locals paid a high price. Unemployment increased as many people were fired from their jobs. An SCLC official later said St. Augustine was the "toughest nut to crack." King called it the "most lawless" place he had protested in.

Desegregation in St. Augustine

Brock led a meeting of 80 local businessmen to decide how to respond to the new law. Brock told reporters that most of his colleagues, though against it in principle, agreed to follow the law. They were worried about how the KKK would react. Brock asked for U.S. Marshals to protect them from "mob action." However, the government refused to send federal marshals. St. Augustine became a "nightmare" for King and the SCLC. On July 4, Brock, speaking for the hotel and restaurant owners, said they wanted to "get our community back to normal."

Segregationist Protests at Monson

On July 9, 1964, James Brock welcomed the first black guests to the Monson Motor Lodge restaurant. Protesters greeted visitors at the entrance, and the Confederate flag flew. Black people who tried to eat at Monson were beaten and driven away.

The Monson Motor Lodge and its restaurant became the center of a violent battle between civil rights supporters and white supremacists after black people were banned from the facility in June 1964. The business kept changing between segregation and integration as the manager, James Brock, tried to keep his business open during the rising racial violence after the Civil Rights Act passed that summer. In a few weeks, the business faced protests from thousands of civil rights supporters—including seventeen rabbis and Jewish activists who came at the request of Reverend Martin Luther King Jr—a Klan-sponsored fire-bombing of the restaurant, and Brock pouring acid on black customers in the motel pool.

Re-segregation of the Monson Motor Lodge

By July 16, Brock had re-segregated, possibly to avoid punishment from local KKK members. However, this didn't stop the violence. The Monson was firebombed by an out-of-state gang. A few days later, the KKK held their biggest march yet. The SCLC had sued about 30 St. Augustine restaurants to force them to integrate. Brock testified in court about his frustration in trying to follow the new law. He asked the court to stop the KKK picketers.

Legal Hearings

After a two-day hearing, Florida Chief Justice Simpson ordered that black people be allowed to eat at two restaurants in St. Augustine. Brock testified that he had asked a local KKK leader to stop the picketing when he first started serving black customers. Brock told the court he was "a little bit afraid to be talking like this" and asked the judge not to make him answer who was with the KKK leader. Simpson ordered Brock to have a bodyguard for the rest of the hearings.

Simpson's judgment was the first federal ruling under the new Civil Rights Act. All parties were ordered to stop breaking the law. Brock and his colleagues had to desegregate again, "regardless of threats." Brock did so, despite threats from the KKK. On July 23, businessmen met at the Monson to discuss legal options. The next morning, two white men threw a molotov cocktail into the Monson lobby, causing damage. After this, businesses that had started serving black customers stopped again.

Dr. King Visits St. Augustine Again

On August 5, King returned to St. Augustine. He was concerned because the struggle there had taken a lot of time and effort. King had many other events planned.

Segregationist Backlash

The next day, the Monson Motel was firebombed. Judge Simpson ordered Brock and his colleagues to obey the law and integrate again. This gave them an excuse to take down "WHITES ONLY" signs. They could say, "what else can we do?" Simpson also issued a restraining order against local KKK leaders. Not everyone felt sorry for the St. Augustine businesses. The State Attorney believed businesses had encouraged white thugs to confront black protesters. He felt they couldn't complain now that the "monster" they created was out of control. Some restaurant owners even held KKK fundraisers and gave free meals to KKK leaders.

Brock released another statement saying, "We deplore the action of the Congress and the Courts in enforcing integration...integration of places of accommodation is obnoxious to us." Some of Brock's colleagues put signs above their cash registers saying money from black customers would go to Barry Goldwater's presidential campaign, as he was against integration.

Tourism Downturn

The civil rights protests in June–July 1964 severely damaged St. Augustine's tourism. One report said tourism was down by at least 50 percent, and many motel owners faced bankruptcy. It's estimated that St. Augustine lost about 122,000 tourists and millions of dollars because of the protests. An investigative committee blamed King, the KKK, newspapers, and television for the problems. They said the problems could have been solved peacefully without "outside agitation." The committee also said St. Augustine taxpayers effectively paid for King's visit.

Racial Tensions

St. Augustine celebrated its 400th anniversary the next year. Tourists came, but racial tension remained. Although businesses changed their policies by 1965, black people were still unsure where they stood. Few dined out in white motels or restaurants. One person later said, "You can be pretty sure that if you eat at a white restaurant and they know who you are, your boss will be told that you're trying to stir up trouble."

Brock's Bankruptcy

Tourism helped the city's economy, and hotels were fully booked. However, Brock did not do well. St. Augustine's main bank refused to give him loans for costs from the protests. On May 2, 1965, he declared bankruptcy. He said he had hoped something good would happen, but since June 11, the day he had Martin Luther King Jr. jailed, there had been a "stigma" he couldn't shake. He claimed he had always been moderate and would integrate if the bill passed.

Official Report

Nearly two years after the protests, in June 1965, the Florida investigative Committee published its report, Racial and Civil Disorders in St. Augustine. The committee blamed both the KKK and the SCLC equally. They emphasized that "out of town" people, not local residents, caused the trouble. Wade-ins and swim-ins remained a key tactic for black Floridians even after the Civil Rights Act passed. These protests helped integrate other areas of society, like parks and schools.

What Happened Later

Fate of the Monson Motor Lodge

Brock sold the Monson in 1998. The motel and pool were torn down in March 2003 after five years of protests. Those who opposed the demolition argued that it would destroy an important landmark of the civil rights movement. Author David Nolan said people claimed the motel had no historical importance, even though a major civil rights protest happened there. The owner wanted to build a new hotel. Opponents believed the site could attract more black tourists to Florida. A city planner said, "the Monson is not the only historical site [in St. Augustine]...This one just happens to have Martin Luther King involved." The Hilton Bayfront Hotel was built on the site. The steps of the Monson, where Brock and King talked, have been saved with a plaque to remember King's activism. Brock, interviewed in 1999, said he had "nothing to be ashamed of" because he was following the law at the time.

Jewish Commemoration

On June 18, 2015, the St. Augustine Jewish Historical Society remembered the arrest of the rabbis 41 years earlier. The event, called "Why We Went to St. Augustine," included a public reading of the letter the rabbis wrote together in jail that night.

In Photographs and Film

Many famous photographs were taken during the integration. One, by an Associated Press photographer, showed Officer Billitz jumping into the pool. This photo appeared on the front pages of the Miami Herald and New York Times the next day. Photos of Brock pouring acid into the pool made international news. They also helped King's "war of images." This photograph has been called "infamous." Because of the timing, the swim-in was guaranteed to be headline news on ABC, CBS, and NBC evening news bulletins.

|

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |