Aletta Jacobs facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Aletta Jacobs

|

|

|---|---|

Jacobs, 1895-1905, by Max Büttinghausen

|

|

| Born |

Aletta Henriëtte Jacobs

9 February 1854 Sappemeer, Netherlands

|

| Died | 10 August 1929 (aged 75) |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Alma mater | University of Groningen |

| Known for | First Dutch female to complete a university degree (medical doctor) |

| Spouse(s) | Carel Victor Gerritsen |

| Children | 1 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Medicine |

| Influenced | Feminism in the Netherlands |

Aletta Henriëtte Jacobs (born February 9, 1854 – died August 10, 1929) was a Dutch doctor and a strong supporter of women's suffrage (the right for women to vote). She was the first woman to officially attend a Dutch university. This made her one of the first female doctors in the Netherlands.

Aletta Jacobs was a leader in both the Dutch and international women's movements. She worked hard to improve working conditions for women. She also promoted peace and fought for women's right to vote.

Born in the mid-1800s, Aletta wanted to be a doctor like her father. Even though it was very hard for women to get a higher education then, she succeeded. She graduated in 1879 with the first medical doctorate earned by a woman in the Netherlands.

She provided medical care to women and children. She became worried about the health of working women. She saw that laws did not protect their health enough. This also affected their ability to earn money. She opened a free clinic to teach poor women about staying clean and caring for children. Aletta continued to be a doctor until 1903. But she spent more and more time working to improve women's lives.

From 1883, Aletta Jacobs challenged the authorities about women's right to vote. She worked her whole life to change laws that limited women's equality. She successfully campaigned for mandatory break laws for retail workers. She also helped Dutch women get the right to vote in 1919.

Aletta was involved in the international women's movement. She traveled worldwide, speaking about women's issues. She also wrote about the social, economic, and political situation of women. She helped start the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. She was also very active in the peace movement. She is known around the world for her important work for women's rights and status.

Contents

A Young Dreamer (1854–1879)

Aletta Henriëtte Jacobs was born on February 9, 1854, in Sappemeer, Netherlands. She was the eighth of 11 children. Her family was of Jewish heritage. Her father was a doctor. From a young age, Aletta became interested in medicine because of him.

She went to the village school and learned needlecrafts. She finished school in 1867. At that time, there were no higher education options for women. She tried a "finishing school" for two weeks. But she felt it was a waste of time. To keep learning, Aletta worked as a dressmaker's helper. She also studied at home. Her mother taught her French and German. Her father taught her Greek and Latin.

Aletta wanted to be a doctor like her father. But higher education in the 1800s was not open to women. A family friend, Levy Ali Cohen, encouraged her. He suggested she become a pharmacy assistant. In 1869, a woman was allowed to take that exam. Aletta studied with her father, her pharmacist brother Sam, and Cohen. She passed the exam in July 1870 and got a diploma.

Cohen and Samuel Siegmund Rosenstein, a university leader, encouraged her to study more. They wanted her to prepare for the university entrance exam. She got permission to listen to classes at the local high school. This made her the first Dutch woman to attend high school.

Aletta learned that a male student who passed his pharmacy exam was allowed into university without the entrance exam. So, Aletta secretly wrote to the head of the Dutch government, Johan Rudolph Thorbecke. She asked for permission to start university studies early. Thorbecke gave her temporary approval to attend for one year.

On April 20, 1871, Aletta entered university. She knew that her success would affect other women's chances for education. A few months later, Thorbecke became very ill. Aletta's father insisted she be allowed to register without probation. On May 30, 1872, Aletta officially became a medical student.

Despite getting sick sometimes, she passed her first medical exam in April 1877. She passed the final test in April 1878. She got her license to be a general practitioner in 1878. Then she started her final project, called a doctoral thesis. It was about how the brain works. At that time, the brain was not studied much.

She graduated on March 8, 1879. Aletta Jacobs was the first woman to attend a Dutch university. She was also the first Dutch woman to get a medical degree. And she was the first to earn a medical doctorate.

News of her achievements was in newspapers across the country. Aletta received many congratulatory letters. One was from Carel Victor Gerritsen, a social reformer. He encouraged her and introduced her to other women doctors. Aletta and Gerritsen started writing to each other. They would not meet for several years.

After graduating, she learned more by watching women doctors in London hospitals. She met Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the first woman doctor in England. She also met Elizabeth's sister, Millicent Fawcett. Both women were deeply involved in the fight for women's suffrage. Aletta also met other reformers. These people influenced her ideas about social change.

Helping Others (1879–1887)

Aletta returned to the Netherlands in September 1879. She planned to attend a medical conference. But she received so many requests for medical help. So she decided to stay and open her own practice. She treated women patients. She was helped by Cornélie Huygens. At that time, women doctors were not allowed to treat men.

Aletta became more and more concerned about working-class women. She saw their poor living and working conditions. She realized that poor women did not know much about staying clean or caring for children. She started free clinics twice a week to advise them. But so many people came that she had to offer more sessions.

In 1883, during elections, Aletta learned that women were not specifically forbidden from voting. So she wrote to the mayor of Amsterdam. She asked why she was not on the voter list. She showed that she met all the requirements to vote. The city replied that while women might not be banned, tradition meant she would need to prove women deserved full citizenship.

Aletta appealed to the Amsterdam District Court. The court said women were not citizens. She then appealed to the Supreme Court. This court ruled that since husbands and fathers paid taxes for married women and children, women were not citizens who could vote. This ignored the fact that Aletta paid taxes as an unmarried woman. By 1884, Aletta's friendship with Gerritsen became a romance.

Aletta joined a group called the Neo-Malthusian League of Holland. She and her husband worked to improve conditions for the poor. In 1886, Aletta started a campaign. She wanted stores to provide benches for employees to rest. At that time, female employees often stood for over 10 hours. This caused serious health problems. Twenty years later, laws were passed to require breaks.

In 1885, a change to the constitution was suggested. It would add the word "man" to the voting rules. The Constitution of 1887 was adopted. It clearly gave voting rights only to male residents.

Fighting for Change (1888–1903)

In 1888, Gerritsen helped start a progressive political group. He was elected to the City Council of Amsterdam. He strongly supported voting rights for everyone. He also wanted required education and social reforms. These included minimum wages and limits on working hours. In 1892, he helped start the Radical League. This was the first Dutch political party to allow women members. Both he and Aletta were active in the party. It supported voting rights for all and separation of church and state.

Aletta and Gerritsen decided to get married on April 28, 1892. They wanted to have children. On September 9, 1893, Aletta gave birth to a son. She kept her own name after marriage. Sadly, the baby lived only one day. This was due to a problem during the birth.

Aletta was one of the founders of the Vereeniging voor Vrouwenkiesrecht (Society for Women's Suffrage) in 1894. But she could not attend the first meeting. She had surgery after her child's birth. Around the same time, she closed her free clinics for the poor.

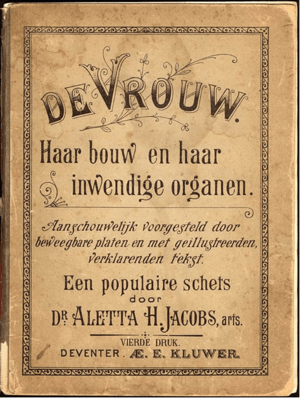

From 1880 to the late 1890s, Aletta focused on her medical practice and politics. She wrote articles and traveled with Gerritsen. In 1894, she wrote articles in newspapers about the health of shop workers. In 1897, Aletta published a book called De Vrouw: Haar bouw en haar inwendige organen (The Woman: Her construction and her internal organs). This was an important book. It described a woman's body and reproductive system. It had movable pictures with explanations. The book was reprinted six times.

In 1899, Aletta published Vrouwenbelangen: Drie vraagstukken van aktuelen aard (Women's interests: Three current issues). This book talked about women being financially independent. It also discussed women's right to plan their family size. She argued that women should be economically and politically independent. She believed women should decide how many children to have.

She attended a big women's conference in London in 1899. This greatly affected her. She started to think about focusing all her efforts on getting women the right to vote. She saw this as a way to remove other barriers for women. By 1900, the Society for Women's Suffrage had about 20,000 members.

In May 1900, Aletta helped start a group to improve opportunities for nurses. She wrote articles about international nursing. She also edited the group's journal. Starting in 1900, Aletta translated feminist books into Dutch. In 1901, she and Gerritsen joined a new political party. Aletta regularly wrote articles about women's working conditions. In 1903, a draft law was published to improve working conditions. Aletta retired from her medical practice in 1903. After that, she spent all her time on women's right to vote. She paid for her work by selling her private library.

The Fight for the Vote (1903–1919)

In 1903, Aletta became president of the Society for Women's Suffrage. She held this position for 16 years. In 1904, she traveled with her husband to Berlin. They attended a conference for women's groups. There, she joined suffragists who formed the International Alliance of Women (IWSA). After the conference, they traveled across the United States. They wrote a book about their trip.

During their travels, Gerritsen became ill. He died in 1905 from cancer. Aletta was very sad. After recovering, she continued her work for voting rights in 1906. She toured with Carrie Chapman Catt through the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Aletta led the organization of the 1908 IWSA Congress. This was the first one held in the Netherlands. It took place in Amsterdam in June. Many international delegates came. This helped the Dutch suffrage movement grow. In 1910, she traveled to South Africa. Activists invited her to help them organize. She toured from Cape Town to Johannesburg. She gave speeches on voting rights, hygiene, and cleanliness.

In 1911, after another IWSA conference, Aletta and Catt went on a 16-month tour. They wanted to see women's legal and social situations. They also wanted to encourage women to fight for improvements. The trip took them to South Africa, the Middle East, India, Sri Lanka, the Dutch East Indies, Myanmar, the Philippines, China, and Japan. Aletta paid for the trip by writing articles about their adventures for a newspaper.

In 1914, soon after World War I started, Aletta suggested holding the International Women's Congress in The Hague. The Netherlands was neutral in the war. This meeting was for women from all over the world. They met to discuss opposing the war. The meeting was led by Jane Addams, a pacifist from Chicago.

Aletta, Mia Boissevain, and Rosa Manus organized the conference. It opened on April 28, 1915. There were 1,136 participants from neutral and non-fighting countries. This conference led to the creation of an organization. It would later become the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). Aletta became the vice-president of both the international organization and the Dutch chapter of WILPF.

After the conference, Addams and Jacobs, along with others, formed two groups of women. They traveled to meet European leaders. They wanted to discuss peace. The women got leaders to agree to participate in a neutral mediating body. This would happen if other nations agreed and if US President Woodrow Wilson started it. But Wilson refused during the war.

In 1917, Dutch women gained the right to run in elections. But they still could not vote. Aletta ran as a candidate in the 1918 election. She received more votes than any other woman candidate. But she was not elected. In 1918, Aletta helped start a journal. She wrote several articles for it. A bill for women's suffrage was introduced and passed in 1919. Queen Wilhelmina signed it on September 18, 1919. Soon after, Aletta resigned as president of the Society for Women's Suffrage.

Later Life (1919–1924)

After women won the right to vote in 1919, Aletta left Amsterdam. She moved to The Hague. From 1922 to 1923, Aletta was on the advisory board of the Voluntary Parenthood League. This group was started by Mary Dennett. The next year, Aletta was a special guest at their annual conference in New York City.

Aletta lost most of her money in bad investments. Her friend Mien van Wulfften Palthe-Broese van Groenou supported her. From 1923 to 1924, Aletta worked on her autobiography (the story of her own life). She lived in her own home so she could spread out her papers and journals. After finishing her autobiography, she lived with the Broese van Groenou family. She continued to attend conferences for women's groups until she died.

Death and Legacy

Aletta Jacobs died on August 10, 1929, in Baarn. She was on holiday at a hotel. After her body was cremated, her ashes were placed in a family mausoleum until 1931. Then they were placed with her husband's ashes in a cemetery in Driehuis.

In the Netherlands, many awards and places are named after her. For example, the Aletta Jacobs Prize is given by the University of Groningen. There is also a college in Hoogezand-Sappemeer. A small planetoid is named after her. A plaque with her picture is on her former house in Amsterdam. From 2009 to 2013, a women's history institute was named the Aletta Institute for Women's History in her honor. Her personal papers are kept at this institute. Her life was made into a film in 1995.

In 1903, when she retired, Aletta sold her collection of 2,000 books, magazines, and pamphlets about women's history. These went to a library in Chicago. The library added English books to her collection, which mostly had Dutch, French, and German titles. This doubled the collection size. In 1954, the University of Kansas bought this collection. It has books from the 1500s, but mostly focuses on women from the 1800s and early 1900s. It includes works on anti-feminist views, women's education, women's legal status, voting rights, and women's economic and work history. It is an important resource for studying women's history.

At a time when married women often had to give up their names and jobs, Aletta kept her own identity. She continued to work outside her home. This inspired others to do the same. Her pioneering clinic was opened decades before similar clinics in the United States and England. Aletta played an important role in helping women who followed her. She helped establish clinics across Europe and the United States by the time she died.

Her campaigns for better working conditions for women and the right to vote were successful. They changed Dutch law. Her work in the peace movement led to the creation of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. Aletta wrote a letter in 1928 about her own career. She said she was happy that three big goals of her life came true:

- Women could study and practice in all fields.

- Motherhood became a choice, not just a duty.

- Women achieved political equality.

Selected works

English version: Memories; My Life as an International Leader in Health, Suffrage, and Peace translated by Annie Wright Translations & edited by Harriet Feinberg. The Feminist Press at CUNY, 1996.

See also

In Spanish: Aletta Jacobs para niños

In Spanish: Aletta Jacobs para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |