David Nelson (abolitionist) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

David Nelson

|

|

|---|---|

Reverend David Nelson, M.D.

|

|

| Born | September 24, 1793 Jonesborough, Tennessee, U.S.

|

| Died | October 17, 1844 (aged 51) Quincy, Illinois, U.S.

|

| Education | Washington College, Tennessee College of Physicians of Philadelphia |

| Organization | Presbyterian Church Marion College American Anti-Slavery Society Mission Institute Underground Railroad |

| Known for | Founder of two colleges Fugitive in Marion County Lyrics to "The Shining Shore" Mentor to Elijah Lovejoy The Cause and Cure of Infidelity |

| Spouse(s) | Amanda Frances Deaderick (m. 1822) |

| Children | Survived by 11 children |

David Nelson (born September 24, 1793 – died October 17, 1844) was an American Presbyterian minister and doctor. He was also a strong activist against slavery, known as an abolitionist. He started Marion College and was its first leader. This college was the first higher education school officially recognized in Missouri.

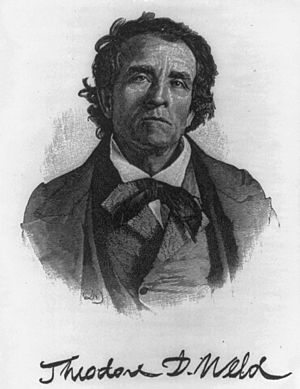

David Nelson was born in Tennessee. He used to own slaves, but he became a passionate abolitionist after hearing a speech by Theodore D. Weld. Because he was against slavery, many people who supported slavery in Missouri did not like him. He left his role at Marion College in 1835.

In 1836, Nelson had to leave Missouri and go to Quincy, Illinois. This happened after a slave owner was hurt during one of his sermons. Nelson stayed in Quincy and started the Mission Institute. This school trained young people to become missionaries. The Mission Institute was openly against slavery, and two of its locations became important stops on the Underground Railroad. They helped African Americans escape to Canada to be free from slavery.

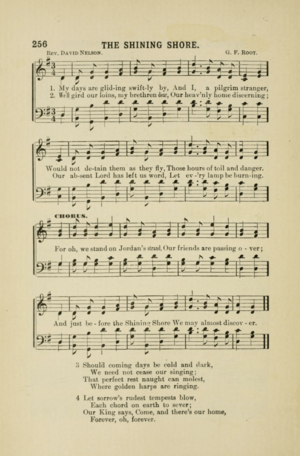

Nelson wrote a book called The Cause and Cure of Infidelity, which shares his journey to becoming a Christian. He also wrote the words for "The Shining Shore," a popular hymn. People say he wrote this poem while he was hiding in Marion County, Missouri, looking across the Mississippi River towards Quincy, Illinois.

Contents

Early Life and Education

David Nelson was born in 1793 near Jonesborough in East Tennessee. His parents, Henry and Anna Nelson, were from Virginia. His father was a leader in the Presbyterian Church, and his mother was a teacher. Both taught at Washington College. David went to Washington College and finished his studies in 1809 when he was sixteen.

Becoming a Doctor

Nelson first studied medicine in Danville, Kentucky, with Ephraim McDowell, a pioneering surgeon. Then he went to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, where he earned his medical degree in 1812. At age nineteen, he planned to practice medicine in Kentucky. But the War of 1812 started, so he joined a Kentucky army group and went to Canada as a military doctor.

After the war, he returned to Jonesborough, Tennessee. He opened a medical practice and earned a good income. In 1816, he married Amanda Frances Deaderick. Her father did not approve of Nelson, who was known for playing cards and gambling. So, they ran away to get married.

At this time, newspapers against slavery were being published in Jonesborough. However, Nelson owned slaves for many years in Tennessee and Kentucky. He only became against slavery much later when he moved to Missouri.

Becoming a Minister

Nelson had doubted his faith for a while, but he had a change of heart. He began studying religion privately with Reverend Robert Glenn. He was inspired by a missionary named Elias Cornelius, who gave a sermon in Tennessee. In 1825, Nelson was allowed to preach, and six months later, he became an ordained minister in Rogersville, Tennessee. For two years, Nelson preached in East Tennessee. He also traveled with Frederick Augustus Ross through Ohio, Tennessee, and Kentucky, preaching in churches and at revival meetings.

In 1828, David Nelson became the pastor of the Presbyterian Church in Danville, Kentucky. He also traveled a lot in Kentucky, teaching medicine classes. Reverend Nelson became known as a very skilled speaker and preacher. He was tall, strong, and had a powerful singing voice, which he used well during church services.

Starting Marion College

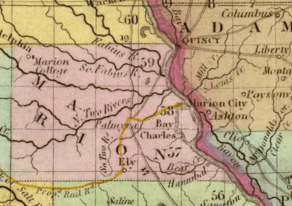

In 1830, Reverend Dr. David Nelson moved to Missouri. He settled in what is now Union Township, about 13 miles northwest of Palmyra, in Marion County. He was sent there by the American Home Missionary Society, along with other Presbyterian ministers.

Nelson soon had the idea to start a Protestant college. He wanted to educate "hardworking young men, farmers and mechanics." He got financial help from two partners: Dr. David Clark and William Muldrow, a farmer and investor. The three founders imagined a manual labor college that would eventually support itself. Students would work on the land for three hours a day. Later, they decided to add a seminary for religious studies, a preparatory school, and a literature department.

In 1830, Nelson and his partners asked the Missouri legislature to approve Marion College. On January 15, 1831, Marion College became the first higher education school to be officially recognized in the state. It was also allowed to give out college and university degrees. The founders received eleven acres of land and built their first school building, a log cabin. In 1832, Dr. Nelson became the first president of Marion College and its first teacher.

Nelson traveled to raise money for the school. The Presbyterian Church's education board promised $10,000 to buy more land, but the agreement fell apart. In 1833, Muldrow, Nelson, and Clark got a $20,000 loan from a New York City bank to buy 4,000 acres of land. In 1834, the three founders collected $19,000 in donations from people in the East.

By the winter of 1834, Marion College had one main building and several small cottages. A local newspaper estimated there were only 20 to 30 students. However, a supportive religious almanac said there were as many as 60 students. By the fall of 1835, the college had 80 students, with 52 of them from other states like New York and Ohio.

In 1835, Dr. Nelson resigned as president of Marion College. He likely did this to calm down groups in Missouri who supported slavery. Reverend William S. Potts took over as president. Marion College faced money problems and eventually closed by 1844.

Fighting Against Slavery in Missouri

In early 1832, the First Presbyterian Church in St. Louis held a big revival meeting. Reverend William S. Potts invited Reverend David Nelson to speak. Nelson helped the church gain 126 new members that year. One of these new members was Elijah Parish Lovejoy, who decided to become a minister.

Around this time, the abolitionist Theodore Weld was in St. Louis. Reverend Dr. David Nelson became an antislavery activist after hearing one of Weld's talks. It is said that Nelson declared, "I will live on roast potatoes and salt before I will hold slaves."

Nelson was a major influence on Elijah Lovejoy, both in their shared faith and their fight against slavery. Nelson later wrote about the teachings of Charles Finney and the Second Great Awakening and how they related to slavery. These writings appeared in the St. Louis Observer, an evangelical newspaper run by Lovejoy.

In 1835, Nelson attended a Presbyterian Church meeting in Pittsburgh and heard Theodore Weld speak again. The American Anti-Slavery Society then chose David Nelson to be one of its agents. Another professor from Marion College, Job Halsey, was also chosen. As an agent, Nelson recruited white and Black antislavery activists in Marion County. He and his followers started Sunday schools to teach African Americans to read the Bible. They also shared writings against slavery, which angered many local people.

Growing Tensions in Marion County

In 1836, many people from Pennsylvania, Ohio, and other Eastern states moved to Marion County. Many of these newcomers were against slavery. Local residents who supported slavery did not trust them and saw them all as "abolitionists."

Two men named Garrett and Williams, who worked for the American Colonization Society, moved to Philadelphia, Missouri. They were bringing hundreds of pamphlets into Marion County. These pamphlets supported colonization, which was the idea that enslaved people should be freed and sent to Africa. A group of armed men led by Captain Uriel Wright found Garrett and Williams. They took them prisoner and found a box of pamphlets hidden. The mob threatened to kill Garrett and Williams unless they left Missouri for good. The mob then publicly burned the pamphlets in Palmyra.

That same day, a group rode to Dr. Nelson's house and surrounded it. They demanded that he hand over any antislavery pamphlets. Nelson warned them to leave, and the mob left, threatening to return for him.

After this, many public meetings were held in Marion County. People spoke out against anyone suspected of being against slavery, and many citizens vowed to force them out. On May 21, 1836, Professor Ezra Stiles Ely had to explain Marion College's role in the abolition movement. Ely admitted he was against slavery but denied supporting abolitionism and claimed to own a slave. Garrett and Williams left for Illinois and later became Nelson's students in Quincy.

Life as a Fugitive

On May 22, 1836, David Nelson was forced to flee to Illinois after violence broke out in Marion County. Reverend Nelson had just given a Sunday sermon at his church. After his sermon, William Muldrow gave him a paper to read. It was a request for donations to help free slaves and send them to Liberia. Nelson was worried it would cause trouble again, but Muldrow convinced him to read it.

Attack on Dr. John Bosely

Dr. John Bosely, a slave owner and church member, was angry that Nelson had talked about slavery. He rushed toward Nelson with a cane. Muldrow tried to stop Bosely, explaining that he had insisted Nelson read the paper. A fight started. Nelson's son said that several men with red handkerchiefs rode off to gather a mob. Nelson started for home, but his wife convinced him to go to Quincy instead.

Escape to Illinois

For the next three days, Nelson hid and traveled only at night until he reached the Mississippi River. He avoided many people looking for him. Meanwhile, two of his friends went to Hannibal, crossed the river, and sent a message to his contacts in Quincy, Illinois. It is believed that Nelson wrote his famous poem, "The Shining Shore," while hiding near the riverbank, waiting to escape.

At dusk, two church members from Quincy pretended to go fishing. They followed signs until Nelson appeared from hiding. On the boat, they fed him. Nelson then went to stay at a hotel in Quincy. The next day, a group of people from Quincy and Missouri came to the hotel. They protested Nelson's arrival and demanded he be given to them. Nelson refused, saying they had no legal papers. John Wood, the founder of Quincy, who later became governor, came to the hotel with 30 armed men to break up the mob.

Back in Missouri, William Muldrow was arrested but later found not guilty. Dr. John Bosely recovered from his injuries. David Nelson arranged for his wife, Amanda, and their many children to wait at a friend's house in Missouri. He arrived at night to take them back to Quincy.

Once settled in Quincy, Nelson sent an open letter to slave-owning Presbyterians in Missouri. It was published in Elijah Lovejoy's newspaper, the St. Louis Observer. The letter asked slave owners to rethink their moral beliefs. In the following years, Nelson avoided public appearances in Missouri because of the ongoing opposition to him.

Opposition in Adams County

On June 10, 1836, a public meeting was called for citizens of Adams County, Illinois. They wanted to oppose the creation of abolitionist groups and any talk about abolition from church pulpits. Before the event, another minister, Reverend Asa Turner, warned church leaders. He prepared for possible mob violence by placing loaded guns under his church pulpit. Turner then gave a controversial sermon. He spoke out against mob violence and slavery, showing his support for Nelson.

Both Nelson and Turner became targets to be "removed" from Quincy. On June 18, a large crowd gathered in Quincy. Joseph T. Holmes, acting as a justice of the peace, warned the group leaders that if they formed a mob, he would use force. After passing a resolution against abolition, the pro-slavery gathering broke up without causing a major incident.

Mission Institute and the Underground Railroad

David Nelson helped set up the Quincy chapter of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1836. He also played a key role in starting the Illinois Anti-Slavery Society in 1837. This society held a meeting in Alton, Illinois, which Nelson attended with his son. The meeting supported Elijah Lovejoy, who had moved his antislavery newspaper to Alton and continued to face mob violence. Lovejoy was killed less than two weeks later, becoming an important figure in the antislavery movement.

When Nelson was an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society in Missouri, he focused on helping slave owners understand that slavery was wrong. Once he moved to Illinois, a free state, he focused on helping enslaved African Americans gain their freedom.

In 1838, Nelson founded an abolitionist college called the Mission Institute. In the years that followed, he helped make Quincy a major entry point for the Underground Railroad. His presence in Quincy made local citizens choose sides in the slavery debate. It inspired many people who were quietly against slavery to take action. Because Quincy was close to Missouri, local residents saw the harshness of slave owners. These owners placed ads in the Quincy Herald and came to Adams County to hunt down runaway slaves. Thanks to Nelson and others, Adams County had more white residents involved in the Underground Railroad than any other county in Illinois.

Starting the Mission Institute

On October 30, 1838, Dr. and Mrs. Nelson gave 80 acres of land for a new college, the Mission Institute. This was in Melrose Township near Quincy and became Mission Institute Number One. It included a chapel and twenty log cabins built by students. In 1840, Nelson started Mission Institute Number Two on an 11-acre site. It eventually had a two-story brick school and 20 to 30 cabins.

The Mission Institute focused on training young people for missionary work in other countries. Graduates went on to serve as missionaries in places like New Zealand and Africa. Others became missionaries in North America, working in Oregon, Iowa, and Canada among people who had escaped slavery.

As more students joined, the Mission Institute received more land from supporters in Quincy. Nelson partnered with Moses Hunter, an abolitionist theologian. Hunter was put in charge of Mission Institute Number Four, also called "Theopolis," which focused on religious studies.

The school itself was later seen as a failure. However, the Mission Institute played a very important role in the Underground Railroad. The leaders, teachers, and students of the Mission Institute were all strongly against slavery. This made it unpopular with local residents. Nelson sent students and graduates to Missouri to preach to African Americans and help many slaves escape to freedom.

The Underground Railroad in Quincy

The Underground Railroad had been active in Quincy since as early as 1830. Because of Nelson's efforts, Mission Institute Number One became the most famous Underground Railroad station in Quincy. The Nelson family home, called "Oakland," was nearby and had a hidden place for people escaping slavery. Mission Institute Number Two also became an important Underground Railroad station.

Quincy became a key entry point for the Underground Railroad in Illinois. The route from Quincy was very similar to the later Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad line.

On March 9, 1843, people who supported slavery set fire to Mission Institute Number Two in Illinois. Historians say that the Mission Institute had become "the special object of hatred by the slaveholders of Missouri." They called it "Nelson College" or the "abolitionist factory." The buildings were burned down by a group of men from Palmyra, Missouri, who crossed the frozen Mississippi River. No one was arrested. Many saw the fire as "fair payback" for the large number of slaves who had escaped from Marion County to freedom through Quincy, Illinois. David Nelson started rebuilding the Mission Institute after it was burned down.

Death and Legacy

David Nelson died on October 17, 1844, in Quincy, Illinois, at age 51. He had been suffering from epilepsy. His partner at the Mission Institute, Moses Hunter, died a few months later. With both leaders gone, the Mission Institute could not continue. In February 1845, the Mission Institute buildings were taken over by another seminary. In the years that followed, the frequent conflicts between groups for and against slavery in Adams County and Marion County seemed to calm down. Nelson is buried at Woodland Cemetery in Quincy, where a marble monument stands in his memory.

"The Shining Shore"

Ten years after Nelson's death, composer George Frederick Root put David Nelson's poem "The Shining Shore" to music. Root's mother found the poem in a religious newspaper and gave it to him. Root only later found out that Nelson had written the words. "The Shining Shore" became very popular during the American Civil War. It is even mentioned in the book Specimen Days by Walt Whitman. In 1907, a book about hymns noted that "The Shining Shore" was "exceedingly popular." More recently, the music group Anonymous 4 performed "The Shining Shore" on their album Gloryland in 2006.

Discovery of a Secret Room at Oakland

In the 1960s, Ruth Deters's family found a hidden room under a trap door in their home, east of Quincy, Illinois. One of her young sons hid from a babysitter, leading to the discovery. Although Ruth and her husband knew Dr. Nelson had built the house, they did not know that "Oakland" had been an Underground Railroad station. It had a secret room and a tunnel that once led out of their basement. Deters then spent decades researching. Her 2008 book, The Underground Railroad Ran Through My House!, explores over 32 Underground Railroad stations in Quincy, including the Mission Institute sites.

Written Works by David Nelson

Books

- The Cause and Cure of Infidelity: A Notice of the Author's Unbelief and the Means of His Rescue

- An Appeal to the Church in Behalf of a Dying Race: From the Mission Institute Near Quincy, Illinois

- Dr. Nelson's Lecture on Slavery

Hymns

- "The Shining Shore" / "My days are gliding swiftly by"

- "Death and Heaven" / "This world explore, from shore to shore"

- "A Better World in Prospect" / "'Twas told me in my early day"

- "Elizabeth Town C. M." / "O Lord, be thou with those who sail"