William Wells Brown facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Wells Brown

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 1814 or March 15, 1815 near Lexington, Kentucky, U.S.

|

| Died | November 6, 1884 Chelsea, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Occupation |

|

|

Notable work

|

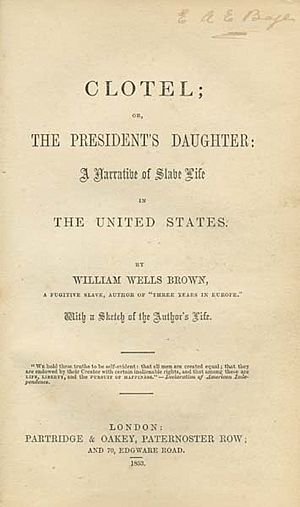

Clotel (1853), the first novel written by an African American |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 5, including Josephine |

| Relatives | Joe Brown (brother) |

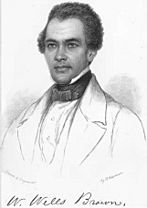

William Wells Brown (born around 1814 – died November 6, 1884) was a very important person in American history. He was an abolitionist, which means he worked to end slavery. He was also a writer, a playwright (someone who writes plays), and a historian.

William Wells Brown was born into slavery in Kentucky. At 19, in 1834, he bravely escaped to Ohio. He later settled in Boston, Massachusetts. There, he became a strong voice against slavery and wrote many books. Besides fighting slavery, he also supported other good causes. These included stopping people from drinking too much alcohol, giving women the right to vote, and making prisons better.

His novel Clotel, published in 1853, is thought to be the very first novel written by an African American. It was first printed in London, England, where he was living at the time. Later, it was published in the United States.

Brown was a pioneer in many types of writing, like travel stories, novels, and plays. In 1858, he became the first African-American playwright to have his work published. After the American Civil War, in 1867, he published what is considered the first history book about African Americans who fought in the American Revolutionary War. He was also one of the first writers to be honored in the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame, which started in 2013. A public school in Lexington, Kentucky is named after him.

William Wells Brown was giving speeches in England when the Fugitive Slave Law was passed in the U.S. in 1850. This law made it much more dangerous for escaped slaves, so he stayed in Europe for several years. He traveled all over Europe. In 1854, a British couple bought his freedom. After that, he and his two daughters returned to the U.S. He then continued giving speeches against slavery in the northern states.

Contents

Early Life and Escape from Slavery

William Wells Brown was born into slavery in 1814 (or March 15, 1815) near Lexington, Kentucky. His mother, Elizabeth, was a slave. She had seven children. William's father was George W. Higgins, a white plantation owner. Higgins said William was his son and asked William's master not to sell him. But William and his mother were sold anyway. William was sold many times before he turned 20.

William spent most of his youth in St. Louis. His masters often rented him out to work on steamboats. These boats traveled on the Missouri River, which was a busy route for trade and the slave trade. Working on the boats allowed him to see many new places.

In 1833, he and his mother tried to escape across the Mississippi River, but they were caught. In 1834, Brown tried to escape again. This time, he successfully slipped away from a steamboat when it stopped in Cincinnati, Ohio. Ohio was a free state, meaning slavery was not allowed there.

After gaining his freedom, he took the names Wells Brown. These names came from a Quaker friend who helped him with food, clothes, and money after his escape. He worked hard to learn to read and write. He read a lot to make up for the education he had missed. Around this time, he worked for Elijah Parish Lovejoy, a famous abolitionist, in his printing office.

Family Life

In 1834, at age 20, William married Elizabeth Schooner. They had two daughters who grew up: Clarissa and Josephine. William and Elizabeth later separated. Elizabeth died in the United States in 1851.

Brown had been in England since 1849 with his daughters. He was giving speeches against slavery. After his freedom was bought in 1854, Brown and his daughters returned to the U.S. They settled in Boston. On April 12, 1860, Brown, who was 46, married Anna Elizabeth Gray, who was 25, in Boston.

In 1856, William's daughter, Josephine Brown, published a book called Biography of an American Bondman. This book was an updated story of her father's life. It used a lot of information from his own autobiography, published in 1847. Josephine added details about the hardships he faced as a slave and new stories about his years in Europe.

Life in New York and Europe

From 1836 to about 1845, Brown lived in Buffalo, New York. He worked on steamboats on Lake Erie. He helped many escaped slaves reach freedom by hiding them on his boat. He took them to Buffalo, Detroit, Michigan, or across the lake to Canada. He later wrote that between May and December 1842, he helped 69 people escape to Canada.

Brown became very active in the abolitionist movement in Buffalo. He joined several anti-slavery groups. He often gave public speeches and used music in his talks. While in Buffalo, Brown also started a Temperance Society, which quickly grew to 500 members. At that time, only 700 black people lived in Buffalo.

In 1849, Brown left the United States with his two young daughters. He traveled to the British Isles to give speeches against slavery. He wanted his daughters to get the education he never had. That year, he also represented the U.S. at the International Peace Congress in Paris.

Because the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed in the U.S., it became very risky for escaped slaves to return. So, he chose to stay in England until 1854. In that year, British friends bought his freedom. As a well-known public figure, he was in danger of being captured and forced back into slavery.

Brown gave many speeches to anti-slavery groups in the UK. He wanted to gain support for the movement in the U.S. He often showed a metal slave collar to show how cruel slavery was. People in Britain were very impressed by him. An article in the Scotch Independent newspaper said he was a "remarkable man" and proved that black people were not inferior.

Brown also used this time to learn about different cultures and ideas in Europe. He felt he always needed to be learning to catch up with others who had received an education when they were young. In his 1852 book about his travels in Europe, he wrote:

He who escapes from slavery at the age of twenty years, without any education, as did the writer of this letter, must read when others are asleep, if he would catch up with the rest of the world.

At the International Peace Conference in Paris, Brown faced challenges because he was representing a country that had enslaved him. Later, he even confronted American slaveholders at the Crystal Palace.

Based on his travels, Brown wrote Three Years in Europe: or Places I Have Seen And People I Have Met. This travel book was popular with readers. He wrote about visiting famous places in Europe.

Abolitionist Speaker and Writer

After returning to the U.S., Brown gave speeches for the abolitionist movement in New York and Massachusetts. He focused on ending slavery. His speeches showed his belief that people could be convinced to support the cause through moral arguments and peaceful actions. He often criticized the idea of American democracy and how religion was sometimes used to make slaves obedient. Brown always argued against the idea that black people were less intelligent or capable.

Because he was such a powerful speaker, Brown was invited to the National Convention of Colored Citizens. There, he met other important abolitionists. When the Liberty Party formed, he chose to stay independent. He believed the abolitionist movement should not get too involved in politics. He continued to support the approach of William Lloyd Garrison, another famous abolitionist. Brown shared his own experiences and insights into slavery to convince others to join the cause.

Literary Works

In 1847, he published his memoir, Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave, Written by Himself. This book became a bestseller in the United States. It was second only to Frederick Douglass's own story. In his book, Brown criticized his master for not having Christian values and for the brutal violence slave owners often used.

While Brown lived in Britain, he wrote more works, including travel stories and plays. His first novel, Clotel, or, The President's Daughter: a Narrative of Slave Life in the United States, was published in London in 1853. It tells the fictional story of two mixed-race daughters of Thomas Jefferson and one of his slaves. This novel is believed to be the first written by an African American.

Most experts agree that Brown is the first published African-American playwright. Brown wrote two plays after he returned to the U.S.: Experience; or, How to Give a Northern Man a Backbone (1856, which is lost) and The Escape; or, A Leap for Freedom (1858). He often read The Escape aloud at abolitionist meetings instead of giving a typical speech.

Brown often struggled with how to truly show slavery "as it was" to his audiences. For example, in an 1847 speech, he said: "Were I about to tell you the evils of Slavery... I should wish to take you, one at a time, and whisper it to you. Slavery has never been represented; Slavery never can be represented."

Brown also wrote several history books. These include The Black Man: His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements (1863) and The Negro in the American Rebellion (1867). The latter is considered the first history book about black soldiers in the American Revolutionary War. His last book was another memoir, My Southern Home (1880).

Later Life and Legacy

Brown stayed abroad until 1854. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Law had made it very dangerous for him to return, even to free states. Only after the Richardson family in Britain bought his freedom in 1854 did Brown return to the United States. He quickly rejoined the anti-slavery lecture circuit.

During the American Civil War and the years that followed, Brown continued to publish books. This made him one of the most productive African-American writers of his time. He also helped recruit black soldiers to fight for the Union in the Civil War.

While still writing, Brown was active in the Temperance movement, giving speeches against alcohol. After studying homeopathic medicine, he opened a medical practice in Boston. In 1882, he moved to Chelsea.

William Wells Brown died on November 6, 1884, in Chelsea, Massachusetts, at the age of 70.

Honors and Achievements

- He was the first African American to publish a novel, Clotel, or, The President's Daughter: a Narrative of Slave Life in the United States, in 1853 in London.

- An elementary school in Lexington, Kentucky, where he spent his early years, is named after him.

- He was one of the first writers inducted into the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame.

- A historic marker shows where his home was in Buffalo.

- A portrait of Wells by artist Edreys Wajed is part of the Freedom Wall in Buffalo. This wall features 28 civil rights icons.

See also

In Spanish: William Wells Brown para niños

In Spanish: William Wells Brown para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |