Lucy A. Delaney facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lucy A. Delaney

|

|

|---|---|

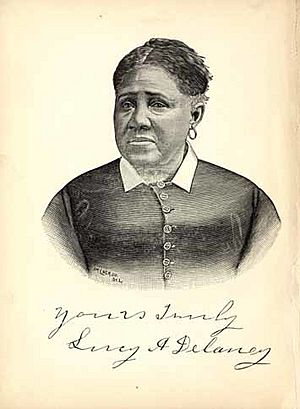

"Yours Truly", Lucy A. Delaney, The New York Public Library Digital Collections

|

|

| Born | Lucy Ann Berry c. 1828–1830 St. Louis, Missouri, United States |

| Died | August 31, 1910 (aged 79–80) Hannibal, Missouri, United States |

| Resting place | Greenwood Cemetery, St. Louis, Missouri |

| Occupation | Author, seamstress, community leader |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | American |

| Notable works | From the Darkness Cometh the Light, or, Struggles for Freedom |

| Spouse |

Frederick Turner

(m. 1845; died 1848)Zachariah Delaney

(m. 1849; died 1891) |

| Parents | Polly Berry |

Lucy A. Delaney, born Lucy Ann Berry (around 1828–1830 – August 31, 1910), was an African-American woman. She was a skilled seamstress, a writer, and a leader in her community. Lucy was born into slavery in St. Louis, Missouri.

As a teenager, Lucy was part of a special type of court case called a freedom suit. Her mother, Polly Berry, had lived in Illinois, which was a free state (meaning slavery was not allowed there), for more than 90 days. According to Illinois law, if enslaved people stayed in the state for over 90 days, they should be set free. Also, a rule called partus sequitur ventrem meant that if a mother was free when her child was born, the child should also be free.

Polly Berry, also known as Polly Wash, first sued for her own freedom. Then, in 1842, she filed a lawsuit for Lucy. While waiting for her trial, Lucy was held in a cold, damp, and smelly jail for 17 months.

In 1891, Lucy Delaney published her life story, called From the Darkness Cometh the Light, or, Struggles for Freedom. This book is the only firsthand account of a freedom suit. It's also one of the few stories by formerly enslaved people published after slavery ended. Her book tells about her mother's legal fight in St. Louis, Missouri, to free herself and her daughter from slavery.

For Lucy's case, Polly got help from Edward Bates. He was a well-known politician and judge. He later became the United States Attorney General for President Abraham Lincoln. Bates argued Lucy's case in court and won her freedom in February 1844. Lucy's and her mother's cases were two of 301 freedom suits filed in St. Louis between 1814 and 1860. Her book shares details about Lucy's life during and after these important lawsuits.

After gaining their freedom, Lucy and her mother lived in St. Louis for a short time. In 1845, Lucy married Frederick Turner, and they moved to Quincy, Illinois. Sadly, Turner died in a steamboat explosion in 1848. Lucy and her mother then returned to St. Louis. In 1849, Lucy married Zachariah Delaney. Lucy's mother lived with them in the Mill Creek Valley area of St. Louis. They had a comfortable life and were active leaders in their community. Lucy and Zachariah had at least four children, but sadly, some died young.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Lucy Ann Berry was born into slavery in St. Louis, Missouri, between 1828 and 1830. Her mother, Polly Berry, was born into slavery in Kentucky around 1803 or 1805. In October 1817, when Polly was about 14, she was taken to Edwardsville, Illinois. After 90 days in this free state, slaveholders were supposed to register their enslaved people as indentured servants, which meant they would eventually be free.

However, in April 1818, Polly was taken to central Missouri, a slave state, and sold. She lived there until about 1823. Then, she was sold to Major Taylor Berry and his wife, Frances (Fannie), in Howard County, Missouri.

Lucy Delaney later wrote about this sale:

Major Berry was immediately attracted by the bright and alert appearance of Polly, and at once negotiated with the trader, paid the price agreed upon, and started for home to present his wife with this flesh and blood commodity, which money could so easily procure in our vaunted land of freedom. Mrs. Fanny Berry was highly pleased with Polly's manner and appearance, and concluded to make a seamstress of her.

—Lucy A. Delaney

Polly married an enslaved man who belonged to the Berry family. They had two daughters, Nancy and Lucy. They lived in Franklin County, Missouri. Major Berry told Polly and her husband that they and his other enslaved people would be freed after his death and his wife's death. But when Major Berry died in a duel, his will did not say that any enslaved people should be freed.

After the major died, his widow Fannie Berry married Robert Wash of St. Louis. He was a lawyer who later became a judge on the Supreme Court of Missouri. Polly and her family remained enslaved, and Polly became known as Polly Wash. Fannie died in 1829. After this, Lucy's family's situation changed. Judge Wash sold Lucy's father to a large farm far down the Mississippi River.

Lucy's biggest fear was being sold and separated from her mother. Like other enslaved mothers in Missouri, Polly encouraged her daughters to plan for the day they could escape.

Lucy, her mother, and sister went to live with Mary, Taylor and Fannie Berry's daughter. Mary married Henry Sidney Coxe in 1837. Nancy, Lucy's sister, was taken with them on their honeymoon trip, which included a stop at Niagara Falls, New York. Polly had already told Nancy to escape into Canada, where slavery was against the law. In Niagara Falls, Nancy got help from a hotel servant and safely crossed the border into Canada.

While Polly was owned by the Coxes, she sometimes worked on riverboats along the Mississippi River and Illinois River. One day, Mary complained about Polly and sold her at a slave auction in St. Louis for $550. Joseph Magehan, a carpenter from St. Louis, bought Polly.

Lucy Delaney took care of Mary Berry and Henry Sidney Coxe's children. The couple had strong personalities and were sad after losing two of their own young children. Mary filed for divorce in 1845 but later changed her mind. They agreed to stay married but lived separately.

Fighting for Freedom

Polly's Freedom Suit

Polly had been held illegally as an enslaved person in Illinois. So, in October 1839, she sued for her freedom in court. Her case was called Polly Wash v. Joseph A. Magehan. When her case finally went to trial in 1843, her lawyer, Harris Sproat, convinced a jury that she had been in Illinois long enough to be free. Polly won her freedom. She then continued her efforts to help her daughter Lucy Ann Berry gain freedom, filing a lawsuit for Lucy in 1842.

Lucy's Freedom Suit

By 1842, Lucy was living with Mary's younger sister, Martha. Lucy was thought to be a gift to Martha when she married David D. Mitchell, who worked for Indian Affairs. Lucy was given the job of doing laundry, which she was not good at. Doing laundry back then was very hard work. It meant carrying many gallons of water, washing by hand with lye, and using heavy irons.

After Martha complained about the ruined clothes and called Lucy lazy, Lucy replied:

You don't know nothing, yourself, about it, and you expect a poor ignorant girl to know more than you do yourself. If you had any feeling you would get somebody to teach me, and then I'd do well enough. She then gave me a wrapper to do up, and told me if I ruined it that as I did the other clothes, she would whip me severely.

—Lucy A. Delaney

After Lucy ruined another piece of clothing, Mary tried to beat her with household items. Lucy managed to take them away. When Mary's husband refused to beat Lucy, they planned to sell her to a farm far away. Before they could, Lucy escaped to her mother's house, who then hid her at a friend's home.

On September 8, 1842, Polly filed a lawsuit for her daughter against David D. Mitchell. Even though Polly's own case had not been decided yet, she could still file a lawsuit for Lucy's freedom as a "next friend." This meant she was acting on behalf of her daughter.

The rule of partus sequitur ventrem meant that a child's status (enslaved or free) followed the mother's. Since Lucy was born to a woman who should have been free, Lucy should also be free. The judge set a $2,000 bond to make sure Mitchell would not try to take Lucy away. Mitchell wanted Lucy kept in St. Louis until the trial. So, Lucy was sent to jail, where she stayed for 17 months.

While in jail, Lucy became sick because of the bad conditions. The jail was crowded, cold, damp, and smelled bad. She did not have enough warm clothes. Her mother visited her, and the jailer's sister-in-law, Minerva Ann (Doyle) Lacy, was kind to her.

In February 1844, Lucy's case went to trial. Francis B. Murdoch, a lawyer from Illinois, prepared the case to free Lucy. He was very involved in freedom suits in St. Louis. The famous politician Edward Bates, who owned enslaved people himself, argued Lucy's case in court. He later became the US Attorney General under President Abraham Lincoln.

By the time Lucy's case went to trial, her mother's case had been settled, and Polly was free. Polly had statements from people who knew her and her daughter. Judge Robert Wash, Polly's former owner, confirmed that Lucy was Polly's child. With the principle of "once free, always free," Bates convinced the jury that Lucy should be freed. The judge announced that she was free. Lucy left jail the same day the decision was made. Once free, Lucy had to register with the city of St. Louis and find someone to support her registration.

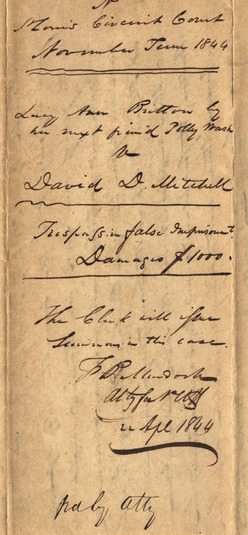

Polly also filed a second lawsuit for her daughter, Lucy Ann Britton v. David D. Mitchell, asking for $1,000 in damages from Mitchell for holding Lucy illegally. Polly and Murdoch might have done this to stop Mitchell from appealing the court's decision. They also wanted payment for the poor conditions Lucy suffered in jail. They later dropped this lawsuit.

Marriage and Family Life

After they were freed, Lucy and her mother worked as seamstresses in St. Louis. In 1845, Lucy met and married Frederick Turner, who worked on steamboats. They moved to Quincy, Illinois, and her mother lived with them. Sadly, Frederick died soon after in a boiler explosion on the steamboat The Edward Bates on August 12, 1848.

Lucy Ann married Zachariah Delaney in St. Louis on November 16, 1849. He was a free Black man from Cincinnati, Ohio. The Delaneys lived in a house on Gay Street in the Mill Creek Valley area of St. Louis. Lucy was a successful seamstress, and Zachariah worked as a porter, cook, and laborer. They were part of the middle class. The Delaneys were married for 42 years until Zachariah's death around 1891. Lucy's mother lived with them. They had four children, but two died when they were very young. Their other son and daughter both died in their early twenties.

After the Civil War, Lucy found her father near Vicksburg, Mississippi. She and her sister Nancy, who had escaped to Canada, were reunited with their father during a visit.

Lucy wrote about finding her father:

I frequently thought of father, and wondered if he were alive or dead; and at the time of the great exodus of negroes from the South, a few years ago, a large number arrived in St. Louis, and were cared for by the colored people of that city. They were sheltered in churches, halls and private houses, until such time as they could pursue their journey. Methought, I will find him in this motley crowd, of all ages, from the crowing babe in its mother's arms, to the aged and decrepit, on whom the marks of slavery were still visible. I piled inquiry upon inquiry, until after long and persistent search, I learned that my father had always lived on the same plantation, fifteen miles from Vicksburg. I wrote to my father and begged him to come and see me and make his home with me; sent him the money, so he would be to no expense, and when he finally reached St. Louis, it was with great joy that I received him. Old, grizzled and gray, time had dealt hardly with him, and he looked very little like the dapper master's valet, whose dark beauty won my mother's heart.

—Lucy A. Delaney

Community Involvement

Lucy Delaney was very active in women's clubs, church groups, and charity organizations. These groups grew quickly in both Black and white communities across the country after the Civil War. She joined the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1855. This church was founded in 1816 in Philadelphia as the first independent Black church in the United States.

Lucy was elected president of the Female Union, which was an organization for African-American women. She also served as president of the Daughters of Zion and the Free Union, another early society for African American women. She was also a leader in the Black women's Masonic movement.

After the Civil War, Lucy was secretary for a group of Black veterans. She belonged to the Col. Shaw Woman's Relief Corps, No. 34. This was a women's group that supported the Col. Shaw Post, 343, of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). The veterans' group was named after the white officer who led the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. This was the first Black unit in the United States Colored Troops and became famous for its bravery in the Civil War. Lucy dedicated her book to the GAR, which had fought to free enslaved people.

Her Published Memoir

In 1891, Lucy Delaney published her book, From the Darkness Cometh the Light, or, Struggles for Freedom. This is the only firsthand story of a freedom suit. Her book is also considered a slave narrative, most of which were published before the Civil War and the end of slavery.

Deborah Garfield, a writer, said this about Lucy's book:

Polly releases motherhood from its ties to 'pure womanhood's' fragility, realigning nurture with liberation. Hardly feminine genuflection, Polly's triumph in male-dominated courts is matched by her daughter's refusal to be whipped. Darkness culminates in Delaney's perpetuating her dead mother's legacy of freedom in her election to numerous civic posts, including the presidency of the 'Female Union'—the first society for African American women—and of the Daughters of Zion.

—Deborah Garfield, The Concise Oxford Companion to African American Literature

Later Life and Legacy

Lucy Delaney passed away at the Negro Masonic Home in Hannibal, Missouri, on August 31, 1910. This home was bought by the Freemasons in 1907 for older members and widows. Her funeral was held at the St. James African Methodist Episcopal Church in St. Louis, organized by the Heroines of Jericho. She was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in St. Louis.

The city of St. Louis often recognizes Lucy Ann Berry's important role in local and national Black History.

See also

In Spanish: Lucy Delaney para niños

In Spanish: Lucy Delaney para niños

- Charlotte Dupuy

- Dred Scott

- Marguerite Scypion

- List of slaves

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |