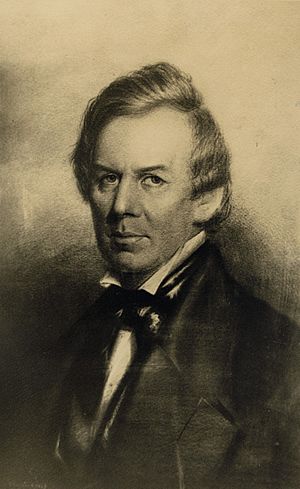

Robert Wash facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Robert Wash

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Missouri Supreme Court Justice | |

| In office 1825–1837 |

|

| Preceded by | Rufus Pettibone |

| Succeeded by | John Cummins Edwards |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 29, 1790 Louisa County, Virginia |

| Died | November 30, 1856 (aged 66) St. Louis, Missouri |

| Resting place | Bellefontaine Cemetery |

| Spouses | Frances Christy Berry Eliza Catherine Lewis Taylor (1837–1856) |

Robert Wash (born November 29, 1790 – died November 30, 1856) was an important judge in Missouri. He served on the Supreme Court of Missouri from September 1825 to May 1837. During his time as a judge, he lived in a period when slavery was legal. He also owned enslaved people. Judge Wash wrote opinions that disagreed with freeing enslaved people in several important cases called "freedom suits." These cases included Milly v. Smith, Julia v. McKinney, and Marguerite v. Chouteau. However, he did agree with the decision to free an enslaved woman in the famous case of Rachel v. Walker.

Judge Wash's decision to separate an enslaved family he owned led to a freedom lawsuit by Polly Wash. Her daughter, Lucy, later wrote a book about her experiences.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Robert Wash was born on November 29, 1790, in Louisa County, Virginia. He was the youngest of seven children. His parents were wealthy and sent him to William and Mary College. He finished college in 1808 when he was 18. For the next two years, he studied law. After that, he was allowed to practice law as a lawyer.

In 1810, he moved to St. Louis in the Louisiana Territory. This area later became the Missouri Territory when Louisiana joined the United States. In St. Louis, he started his own law practice.

Early Public Service

In November 1811, the acting governor, Frederick Bates, chose Robert Wash to be the Deputy Attorney General for the Louisiana Territory. This was an important legal job.

During the War of 1812, Wash served in the military. He was a lieutenant and later helped a general named Benjamin Howard. Wash traveled with General Howard on a trip up the Mississippi River. Their goal was to fight against some Native American groups who were helping the British. However, there was not much fighting in their area.

When Missouri became a state in 1821, St. Louis became an official city. Wash was elected as one of the first nine city leaders, called aldermen. He worked hard to improve the city's roads, sidewalks, and harbor. He believed that strong walls, called dikes, were needed along the river. He thought this would stop sand from blocking the river channel, which eventually happened later.

During his first term as alderman, President James Monroe appointed Wash as the U.S. District Attorney for St. Louis. This meant he was the chief lawyer for the federal government in that area.

Serving on the Missouri Supreme Court

After Judge Rufus Pettibone passed away, Robert Wash was chosen to join the Supreme Court of Missouri. He started his duties in September 1825 and served until he resigned in May 1837. At that time, the state's highest court had only three members. The head of the court was called "Justice," and the other members were called "Judge."

Many important cases were decided while Judge Wash was on the court. A large number of these cases were "freedom suits." These were lawsuits where enslaved people tried to win their freedom. In 1824, Missouri passed a law that made it easier for enslaved people to sue for their freedom. The years between 1824 and 1844 are often called the "golden age" for freedom suits because many enslaved people won their cases during this time. Later, after the famous Dred Scott decision, it became much harder for enslaved people to win their freedom in court.

Here are some important cases that Judge Wash heard:

The Milly v. Smith Case (1829)

In 1826, a man named David Shipman was in debt. His creditors took and sold two of his enslaved people. To avoid losing more, Shipman asked his nephew, Stephen Smith, for help. Shipman then ran away to Indiana with his other seven enslaved people. In Indiana, he signed papers to free them. This included Milly, her three children, and two young men.

The group then moved to Illinois and lived in a Quaker community. Shipman told his new neighbors that the Black people in his home were free. These neighbors later said that the formerly enslaved people could go wherever they wanted.

Meanwhile, Stephen Smith was upset that his uncle had left and that he was responsible for Shipman's debt. Smith wanted to find his uncle and get the enslaved people back, seeing them as valuable property.

Smith found Shipman in Illinois. Shipman admitted his debt but said he had left enough property in Kentucky to cover it. However, Smith wanted the enslaved people. In early 1827, he took five of them and brought them to St. Louis. Members of the Quaker community followed Smith and took the group back, planning to return them to Illinois.

Because of this dispute, the five freed people sued Smith in St. Louis to get their freedom back. Milly and her children spent much of the next five years in jail while their cases went through the courts. In March 1828, a jury decided in Smith's favor.

Two appeals went to the Missouri Supreme Court. In the end, Milly was freed. The court was split 2–1, with Judge Wash disagreeing. He believed that the person who held the mortgage on the enslaved people was the legal owner. He felt that Shipman, who was in debt, did not have the right to free Milly.

The Julia v. McKinney Case (1833)

In Julia v. McKinney, the Missouri Supreme Court had to decide if an enslaved person should be free based on the laws of a free territory or state. Lucinda Carrington, who owned an enslaved woman named Julia, lived in Kentucky. When Carrington said she planned to move to Illinois with Julia, a neighbor warned her that Julia would become free there. To try and avoid this, Carrington went to Pike County, Illinois, with Julia. But she said she planned to hire Julia out in Missouri. Julia stayed with Carrington in Illinois for a month. Then she was hired out in Louisiana, Missouri. When Julia got sick, Carrington had her return to Illinois. After she recovered, Carrington sent her to St. Louis, where she was sold to S. McKinney.

Julia sued McKinney for her freedom in St. Louis. She argued that she and Carrington had lived in Illinois, a free state, for a period of time. The court's instructions to the jury focused on Carrington's intentions, not her actions. The jury was told that if Carrington did not intend to make Illinois Julia's home, then Julia was not free.

The jury decided against Julia. She then appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court. The higher court decided in Julia's favor, with a 2–1 split. Judge Wash disagreed with the majority. The majority said that Illinois's constitution clearly stated that slavery would not be allowed. They believed that Carrington's actions of living in Illinois with Julia, even for a short time, meant she had introduced slavery into a free state.

Judge Wash agreed that the lower court's instructions were wrong. However, he still believed that the owner's intention was important. He argued that simply moving into a state, without intending to live there, should not be enough to make an enslaved person free.

The Marguerite v. Chouteau Case (1834)

Marguerite v. Chouteau was one of several freedom suits that started around 1805. It began with a petition from an enslaved woman named Catiche. She was the granddaughter of a Natchez Indian woman. Catiche was owned by a member of the Chouteau family, who helped found St. Louis. A court first decided in favor of Jean-Pierre Chouteau Sr. But then, a different court reversed that decision.

As Catiche's case continued, her sister Marguerite also sued Chouteau for her freedom. The 1826 case depended on whether Marguerite was considered Native American or Black. It also looked at whether the enslaved status of a Native American person, who had been enslaved before Louisiana was transferred to Spain, continued under Spanish and then U.S. law. Under French and Spanish law, Black people could be enslaved. However, under Spanish law, Native Americans were supposed to be free. The first court decided in favor of Chouteau. Marguerite then appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court.

On appeal, the lower court's decision was upheld because the Supreme Court was evenly split. Judge Tompkins sided with Marguerite, Judge Wash was against her, and Justice McGirk did not participate. With everyone's agreement, the appeal was heard again by the full court. This time, Justice McGirk and Judge Tompkins decided in favor of Marguerite. They said the first court had given wrong instructions to the jury. They ordered a new trial.

In his disagreement, Judge Wash argued that the rights of owners of Native American enslaved people were protected. He said this was true even when territories were transferred between countries. The new trial was moved to Jefferson County. After two trials there, Marguerite was set free. The Missouri Supreme Court confirmed this decision.

This case is seen as the official end of Native American slavery in Missouri.

The Rachel v. Walker Case (1834)

This freedom suit involved an enslaved woman of color named Rachel. The main question was whether an enslaved person became free if they were taken into a territory where slavery was not allowed. Rachel's claim was based on a legal idea that allowed enslaved people to ask for freedom if they were considered "poor people" with "limited rights."

Rachel had traveled with her owner, Lieutenant Thomas Stockton, to Fort Snelling and Fort Crawford. These forts were in Michigan Territory, where Stockton was stationed. According to the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, slavery was against the law in this region. While at Fort Crawford, Rachel gave birth to her son, James Henry. Stockton later sold Rachel and her son to William Walker of St. Louis.

Rachel sued Walker for her freedom in 1834. She argued that she had lived in a free territory. Based on the idea of "once free, always free," she believed she was no longer enslaved. The St. Louis court decided against Rachel. They said that Stockton had no choice about where he lived because the Army decided it. They reasoned that since it wasn't his choice to take Rachel to a free territory, she had no claim to freedom.

Rachel appealed her case to the Missouri Supreme Court in 1836. In a decision that all the judges agreed on, they sided with Rachel. Judge McGirk, speaking for the court, said that Stockton's actions were his own choice, not a necessity. He stated that those who claimed ownership under Stockton had to accept the results of bringing slavery into territories where it was against the law. The court reversed the earlier decision, meaning Rachel won her freedom.

The ruling in Rachel v. Walker was later used as an example in the famous Dred Scott trials.

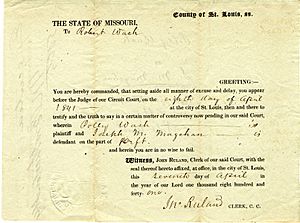

Polly Wash v. Joseph M. Magehan (1839)

Judge Wash was a witness in the freedom suit of Polly Wash v. Joseph M. Magehan. He also testified in the case of Polly Wash's daughter, Lucy. Polly had been bought by Major Taylor Berry as a house servant. When Major Berry died, his widow married Judge Robert Wash. This made Judge Wash responsible for Polly. Polly was married and had two daughters while living with the Berry and Wash families. Polly was eventually sold to Joseph Magehan. Because Polly had lived for a time in the free state of Illinois before she came to the Berry and Wash homes, she sued Joseph Magehan for her freedom. Polly won her freedom. She then filed another freedom suit for her daughter, Lucy, which began in February 1844.

Judge Wash testified in Lucy's case. He said that Lucy was a baby when he took over Mrs. Fannie Berry's property. He often saw Lucy with her mother, Polly, and believed Lucy was Polly's child. Harry Douglas, who used to manage Wash's farm, confirmed this statement. Since Polly should have been free when she gave birth to Lucy, Lucy should also have been free. This was based on a legal idea that a child's status followed their mother's status. The jury decided in Lucy's favor, and she won her freedom.

Personal Life

Judge Wash was married twice. His first wife was Frances (Fannie) Christy Berry. She was the daughter of Major William Christy. They had one daughter, Frances. Sadly, Frances traveled to Pensacola, Florida for her health and died there by February 1829. His second wife was Eliza Catherine Lewis Taylor. She was the daughter of Colonel Nathaniel P. Taylor. They had four sons: Robert, William, Clark, and Pendleton. They also had five daughters: Elizabeth, Virginia, Julia, Medora, and Edmonia.

Wash was a member of the Episcopal Church and served on the church's board.

He was also a big supporter of the City of St. Louis. He believed the city had a great future. As soon as he had enough money, he started buying land. These properties helped him build a large fortune that he enjoyed throughout his life.

In May 1818, Judge Wash was part of a group that planned to build a theater. They bought land and started building the foundation. But they ran out of money, and the project was stopped. A stable for horses was built on the site instead.

Judge Wash's friends and colleagues knew he loved hunting. He kept a group of hunting dogs. There's a story that once, while he was judging a case, a lawyer whispered to him that three foxes had been seen near his home. Judge Wash suddenly got "severe cramps" and had to end court early. Within an hour, he was on his horse, following his dogs. These "sudden attacks" happened often!

After he retired from the court, Judge Wash lived at his St. Louis home with his family and friends. He passed away on November 30, 1856. Robert Wash is buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery.

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |