Timeline of First Nations history facts for kids

The history of First Nations in Canada is a long and amazing journey. It covers the time before Europeans arrived, and continues right up to today. First Nations people have lived in North America since "time immemorial," which means for as long as anyone can remember. Their oral stories and traditional knowledge, along with findings from archaeologists, help us learn about their deep roots in this land.

Many experts believe that people first came to North America from Asia thousands of years ago. They might have traveled by sea or across a land bridge that once connected the two continents. Evidence of humans living in what is now Canada and Alaska dates back as far as 18,000 to 10,000 years ago. Important early sites include places in Alaska, Haida Gwaii in British Columbia, Vermilion Lakes in Alberta, and Debert in Nova Scotia.

Contents

Ancient Times: Before Contact

A report from 1996 by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples described four main periods in Canadian history for Indigenous peoples. These periods often overlapped and happened at different times in various regions. They are:

- Pre-contact: Different Worlds (before 1500s)

- Early Colonies: (1500–1763)

- Displacement and Assimilation: (1764–1969)

- Renewal to Constitutional Entrenchment: (1969 to today)

First People Arrive: 50,000 to 20,000 Years Ago

Some experts believe that humans could have reached North America as early as 50,000 years ago. Evidence of caribou, an important animal for early peoples, dates back 1.6 million years in the Yukon.

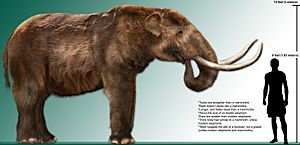

Around 30,000 to 20,000 years ago, possible signs of human activity have been found. For example, chipped mammoth bones were discovered in Bluefish Caves in the Yukon. Some archaeologists think people might have lived in the Americas even before the well-known Clovis culture.

During this time, there was an ice-free path through what is now Alberta. Stone tools found in Alberta suggest that nomadic humans might have lived there before the glaciers covered the land. DNA studies also suggest that people entered the Americas around 25,000 years ago.

Early Hunters and Settlements: 20,000 to 11,000 Years Ago

The Old Crow Flats and Bluefish Caves in the Yukon are some of the oldest known places where humans lived in Canada. This area was not covered by glaciers during the Ice Ages, making it a safe place for plants, animals, and people.

Around 14,000 years ago, the Heiltsuk Nation's oral history describes a coastal land that was a refuge during the ice age. Archaeologists found what seems to be this ancient settlement on Triquet Island in British Columbia. They found a hearth (fireplace) that is about 14,000 years old, making it one of the oldest human settlements found in North America. They also found fish hooks, tools for starting fires, and stone tools.

Between 12,000 and 11,000 years ago, early people hunted large bison, which were bigger than today's bison. These animals were a main food source for First Nations on the Plains and in the Rocky Mountains. The oldest known bison hunting sites date back about 11,000 years.

Life After the Ice Age: 11,000 to 9,000 Years Ago

From 11,200 to 10,500 years ago, archaeologists have found fluted spear points across Canada. These were used for hunting bison and caribou. The Crowsnest Pass in the Canadian Rocky Mountains is a very rich archaeological area, with tools from the Clovis culture dating back 11,000 years.

The Plano cultures lived in Canada from 11,000 to 6,000 years ago. They used special spear points and were skilled bison hunters, often using techniques to make bison stampede off cliffs. They also hunted other animals like deer and elk. They preserved meat with berries and animal fat and stored it in hide containers. As glaciers melted, new areas opened up, and caribou became a major prey animal in northern and eastern regions.

Charlie Lake Cave in British Columbia has continuous evidence of human life for at least 11,000 years. This site suggests that people might have moved north, following bison herds, rather than just south through the ice-free corridor. The Dane-zaa First Nation are descendants of these early people.

Around 11,000 years ago, a salmon-based culture developed on the Northwest Coast. Trade routes for valuable materials like obsidian (a sharp volcanic glass) were also established. Archaeological sites in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia show Aboriginal campsites dating back about 11,000 years. The Debert Palaeo-Indian Site in Nova Scotia is a National Historic Site.

Growing Communities: 10,000 to 5,000 Years Ago

The Vermilion Lakes area in Alberta shows early human activity from 10,800 to 9,000 years ago. From 10,500 to 7,750 years ago, different groups of big-game hunters lived in Alberta, using various stone tools.

The area of Banff National Park has been home to people for 10,000 years, with over 700 archaeological sites found. The Stó:lo people lived in the Fraser River Valley, with evidence of settlements dating back 8,000 to 10,000 years.

Around 8,500 years ago, the Paskapoo Slopes in Calgary, Alberta, were important sites for First Nations. The high ridges offered great views for hunting bison, and river banks were used for winter camps. The steep cliffs were perfect for "buffalo jumps," a clever hunting method similar to the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Around 6,800 years ago, a volcano called Mount Mazama erupted, covering much of western Canada with ash. Archaeologists use this ash layer to help date ancient sites.

About 6,000 years ago, First Nations people made "petroforms" (stone shapes) in Whiteshell Provincial Park in Manitoba. There's also evidence of ancient copper trading and stone tool making in this area. The Ojibway and Anishinaabe peoples used this land for hunting, fishing, and gathering wild rice for thousands of years.

Ancient Burial Sites and Arctic Peoples: 5,000 to 2,000 Years Ago

From 5,000 to 360 years ago, the Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung National Historic Site of Canada in Ontario was a major center for early habitation and ceremonial burials. It has many ancient burial mounds.

Around 4,500 years ago, Palaeoeskimo peoples (ancestors of today's Inuit) arrived in the Arctic from Asia and Alaska. They spread across Greenland and Labrador.

In 1997, a 4,300-year-old dart shaft was found in the Yukon as ice melted, showing how ancient tools can be preserved.

Around 4,000 years ago, the area of L'Anse-aux-Meadows in Newfoundland was occupied by different Aboriginal groups before the Norse arrived. The Dorset people lived there about 200 years before the Norse.

Human sites dating back about 3,000 years have been found on the Slate Islands (Ontario) in Lake Superior. The Pukaskwa Pits, depressions left by early inhabitants, likely Algonkian people, were used for seasonal homes, hunting blinds, or food storage.

Around 2,400 years ago, spear-throwing tools were found in the Mackenzie Mountains, showing the ancient hunting skills of the Mountain Dene people. Corn and farming were introduced to northeastern North America by Indigenous groups as early as 2,300 years ago.

Early Contact and European Influence (1500–1763)

First Encounters and Alliances

Around 1536 to 1632, Basque whalers regularly visited North America, especially Red Bay. They had friendly trade with the Mi'kmaq people, leading to a mixed language (pidgin) that helped them communicate.

By 1580, European goods had reached the Iroquois in the St. Lawrence Valley. In 1603, Samuel de Champlain met the Mi'kmaq people in New Brunswick and Quebec. He noted their large camps and use of copper.

From 1608 to 1760, a strong alliance formed between the French and First Nations. Indigenous peoples taught the French how to survive winters, navigate the land, use birch bark canoes, and make maple sugar. This was a time of important cultural exchange.

In 1610, Henri Membertou, a Mi'kmaq Grand Chief, and many of his family members were baptized, starting a relationship between the Mi'kmaq and the Catholic Church. Chief Membertou was a respected leader who encouraged his people to convert.

Conflicts and Trade

The Beaver Wars (1629–1701) were conflicts between Indigenous peoples in the Great Lakes region, made worse by European trade and the demand for beaver furs. The Iroquois, supported by England and the Dutch, fought against Algonquian allies of the French, including the Huron and Ojibwe.

In the late 1600s, European traders brought diseases like smallpox, influenza, and measles to Indigenous communities. These diseases spread quickly and caused many deaths, especially in busy trading centers.

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) established fur-trading posts, like Moose Fort (now Moose Factory), in the late 1600s. In 1755, the British created the Indian Department to build alliances with First Nations against the French and later the Americans.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was a key document that recognized Aboriginal title to land and the right of Aboriginal self-government.

Changing Lands and Lives (1764–1969)

New Trails and New Ways

In 1793, Nuxálk and Carrier guides helped Alexander MacKenzie travel along ancient trade routes, known as "grease trails," to the Pacific Ocean. These trails were used for communication and trading, especially for eulachon grease.

Around 1799, Makenunatane, also known as "Swan Chief," a leader of the Dane-zaa (Beaver Nation), saw that changes were coming. He encouraged his people to become fur trappers and traders and to accept Christianity.

During the War of 1812, a strong alliance formed between British leaders and First Nations leaders like Tecumseh of the Shawnee. After the war, the roles of Indigenous peoples in colonial society changed rapidly.

In 1839, Upper Canada passed a law to protect Indian reserves, treating them like Crown lands.

Residential Schools and Government Control

The first Indian residential schools were set up in the 1840s. These schools, run by churches and the government, aimed to assimilate Indigenous children into European culture. The last residential school closed in 1996.

In 1867, the Constitution Act, 1867 established Canada as a self-governing country. The government created departments to manage affairs, including a "superintendent-general of Indian affairs."

The Rupert's Land Act 1868 allowed the British Crown to take control of Rupert's Land from the Hudson's Bay Company. This vast area became part of Canada in 1870, but only after treaties were made with the Indigenous nations who lived there.

The first of the numbered treaties, Treaty 1, was signed in 1871 with several Ojibwe and Cree nations in Manitoba. These treaties promised land for First Nations to use forever, where "the white man" would not intrude.

In 1873, a group of American hunters killed over twenty Nakoda Assiniboine people in what became known as the Cypress Hills Massacre. This event led to the creation of the North-West Mounted Police.

The Indian Act, first passed in 1876, is a Canadian law that still governs how the Canadian government interacts with First Nations. It has been changed many times and is a source of much debate.

In 1879, the Blackfoot Confederacy experienced a time they called "when first/no more buffalo," as the American bison herds were nearly wiped out. This greatly impacted their way of life.

Prime Minister John A. Macdonald's National Policy focused on building the Canadian Pacific Railway. Historians have described how the government used starvation to force First Nations onto reserves, clearing the way for the railway.

In 1883, Sir Hector-Louis Langevin, a Father of Confederation, played a role in setting up the residential school system. He believed that separating children from their families was necessary to make them "civilized."

The "pass system" was introduced in 1885, preventing Aboriginal people from leaving reserves without permission and outsiders from entering. This system was not a law but was enforced by Indian agents.

In 1887, the Nisga'a people challenged the distribution of their traditional lands, arguing it violated the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

In 1907, the Horden Hall Residential School in Moose Factory, run by the Anglican Church, served communities in the James Bay area. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission later investigated this and other residential schools, finding high rates of child deaths, especially from tuberculosis.

In 1922, Peter Henderson Bryce published "The Story of a National Crime," raising serious concerns about the conditions in Indian residential schools. He noted overcrowding, poor nutrition, and lack of hygiene led to many deaths.

By 1930, caribou in Newfoundland, vital for the Mi'kmaq, were almost extinct due to overhunting.

In the 1940s, nutrition experiments were conducted on isolated Indigenous communities and in residential schools.

The Sixties Scoop, starting in the 1960s, saw a high number of Aboriginal children removed from their families and placed in foster care or adopted by non-Indigenous families.

In 1967, the Hawthorn Reports concluded that Aboriginal peoples were Canada's most disadvantaged group due to failed government policies, especially the residential school system.

Moving Towards Renewal (1969 to Today)

Seeking Equality and Rights

In 1969, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau's government proposed the "White Paper," which aimed to abolish the Indian Act and end the special legal relationship between Aboriginal peoples and the state. This was met with strong opposition from Aboriginal leaders, who saw it as a way to erase their distinct status. The plan was abandoned in 1970.

In 1973, the Supreme Court of Canada made a landmark decision in Calder v. British Columbia (Attorney General). For the first time, Canadian law recognized that Aboriginal title to land existed before colonization.

The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement in 1975 was a major land claim settlement with the Cree and Inuit of northern Quebec.

Section Thirty-five of the Constitution Act, 1982 (1982) gave constitutional protection to Aboriginal and treaty rights in Canada.

In 1984, the Guerin case further clarified Aboriginal rights, stating that the government has a special duty to First Nations and that Aboriginal title is a unique right.

Important Events and Reconciliation Efforts

The Meech Lake Accord in 1987, a proposed constitutional change, was negotiated without input from Indigenous peoples. In 1990, Elijah Harper, a First Nations politician, famously refused to support the Accord because it did not address Indigenous concerns, leading to its failure.

The Oka Crisis in 1990 was a land dispute between the Mohawk community of Kanesatake and the government, becoming a well-known conflict between First Nations and Canada.

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was established in 1991 to address issues of Aboriginal status. Its 1996 report proposed a 20-year plan for changes.

In 1995, Dudley George was fatally shot by police during a protest at Ipperwash Provincial Park, leading to a public inquiry.

The Nisga'a Final Agreement in 1996 was the first modern treaty signed by a First Nation in British Columbia since 1899. It gave the Nisga'a control over their land and resources.

The 1997 Delgamuukw v. British Columbia Supreme Court decision set a precedent for how treaty rights are understood. It confirmed that oral testimony from Indigenous people is valid evidence and that Indigenous title includes the right to extract resources from the land.

In 2001, the term "First Nation" began to replace "Indian" in Canada, as many communities preferred it.

The Kelowna Accord in 2005 was a plan between the Canadian government, provinces, and Aboriginal leaders to improve Indigenous education, employment, and living conditions with a $5-billion investment. However, the new government in 2006 did not fully support it.

Truth, Reconciliation, and Moving Forward

In 2006, the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA) was reached, the largest class action settlement in Canadian history. It provided compensation to survivors and established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

The TRC was created in 2008 to document and preserve the experiences of residential school survivors. In June 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper formally apologized to residential school survivors in the House of Commons.

In 2007, Canada was one of four countries to vote against the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). However, in 2010, Canada officially endorsed UNDRIP, and in 2016, the government announced its intention to fully adopt and implement it.

The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) was established in 2016 to investigate the systemic causes of violence against Indigenous women, girls, and LGBTQ2S people. Its final report was published in 2019.

In 2017, the Canadian government created two new ministries: Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada and Indigenous Services Canada, to better manage relationships and services for Indigenous peoples.

In 2020, the Wetʼsuwetʼen pipeline and railways protests highlighted ongoing land rights issues. Also in 2020, the tragic death of Joyce Echaquan, an Atikamekw woman, in a Quebec hospital brought attention to racism in the healthcare system.

In May 2021, the Tkʼemlúps te Secwépemc First Nation announced the discovery of the remains of 215 children at the site of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School. This led to the creation of the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation on September 30, a day to remember survivors and reflect on the legacy of residential schools.

In July 2021, Mary Simon, an Inuk leader, became the first Indigenous Governor General of Canada.

In July 2022, Pope Francis apologized for the role of the Catholic Church in the residential school system during a visit to Canada.

These events show the ongoing journey of reconciliation and the importance of understanding the rich and complex history of First Nations in Canada.

See also

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |