Settlement of the Americas facts for kids

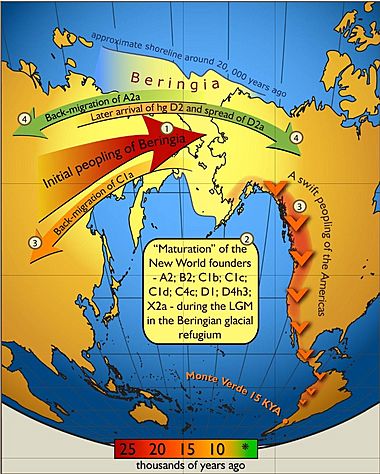

The settlement of the Americas began a very long time ago. Early hunter-gatherers, who lived by hunting animals and gathering plants, traveled from North Asia into North America. They crossed a land bridge called Beringia. This bridge connected northeastern Siberia and western Alaska. It appeared because sea levels were much lower during the Last Glacial Maximum (about 26,000 to 19,000 years ago).

These first people moved south from the huge Laurentide Ice Sheet. They quickly spread across both North and South America by 12,000 to 14,000 years ago. The very first groups in the Americas, before about 10,000 years ago, are known as Paleo-Indians. Scientists have found links between these Indigenous peoples of the Americas and Siberian groups. These links come from their languages, blood types, and DNA.

We don't know the exact date when people first arrived in the Americas. But new discoveries in archaeology, geology, and DNA analysis are helping us learn more. Most experts agree that people first came from Asia. However, how they traveled, when they arrived, and their exact starting points in Asia are still unclear. The "Clovis first theory" used to be popular. It said that the Clovis culture, about 13,000 years ago, was the first human group in the Americas.

But now, we have found older evidence of cultures that existed before Clovis. This means people might have arrived even earlier. Many archaeologists think humans reached North America south of the ice sheets between 15,000 and 20,000 years ago. One idea is that these early travelers followed herds of large, now-extinct animals. They used "ice-free corridors" between the massive ice sheets. Another idea is that they traveled down the Pacific coast, either walking or using simple boats. They might have gone as far south as Chile. Any old coastal sites would now be underwater because sea levels have risen a lot since then. Some findings even suggest people might have arrived more than 20,000 years ago, before the Last Glacial Maximum.

Contents

The Environment During the Ice Age

How the Bering Land Bridge Appeared and Disappeared

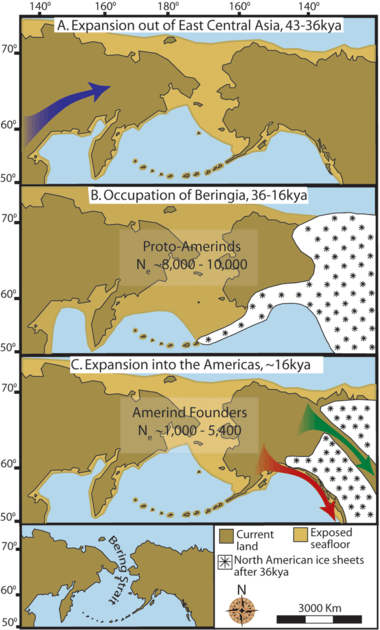

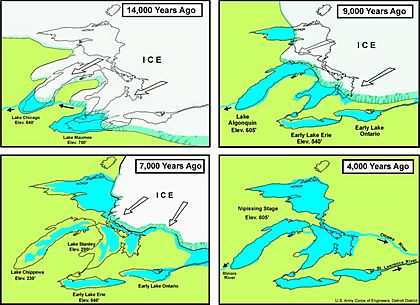

During the Wisconsin glaciation (a major ice age), a lot of Earth's ocean water turned into ice and was stored in huge glaciers. This caused the global sea level to drop. Scientists have figured out how sea levels changed over time by studying ocean cores and old coastlines. When the sea level dropped by about 60 to 120 meters (200 to 400 feet) around 30,000 years ago, it created Beringia. This was a large land bridge connecting Siberia and Alaska.

After the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), sea levels rose again. This caused the Beringian land bridge to be covered by water once more. Experts believe this happened around 11,000 years ago (Figure 1). New research might change this date, which could affect how we understand human migration into North America.

Giant Glaciers and Ice Sheets

After 30,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum, huge glaciers and ice sheets grew very large. They blocked the paths out of Beringia. By 21,000 years ago, the Cordilleran Ice Sheet and Laurentide Ice Sheet joined together east of the Rocky Mountains. This closed off a possible route into the middle of North America. Glaciers in the coastal mountains and the Alaska Peninsula also cut off Beringia's interior from the Pacific coast.

Even during this time, some areas along the coast remained free of ice. These "refugia" supported animals. As the ice melted, these areas grew larger. The coast became ice-free by 15,000 years ago. The glaciers on the Alaskan Peninsula melted, opening a path from Beringia to the Pacific coast around 17,000 years ago. The ice barrier between interior Alaska and the Pacific coast broke up around 16,200 years ago. The "ice-free corridor" into the middle of North America opened between 13,000 and 12,000 years ago.

Climate and Living Environments

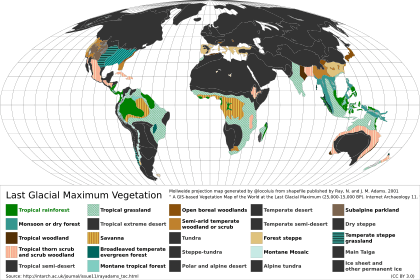

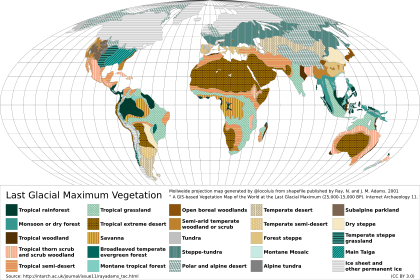

Scientists study old pollen and ice cores to understand the climate and plants in Siberia and Alaska during the Ice Age. Before the Last Glacial Maximum, the climate in eastern Siberia changed between warm and cold periods. During warmer times, many large animals (megafauna) lived there.

As the LGM approached, forests and shrubs in Siberia were replaced by cold, dry "herb tundra." This might be why there are no human sites from the LGM in northern Siberia. In Alaska, the changes were less dramatic, but herb tundra still took over. Large animals were present, though perhaps not in huge numbers.

Coastal areas were also complex. Lower sea levels created a coastal plain. While much of it was covered in ice, some ice-free areas (refugia) existed on islands like Haida Gwaii. These areas supported land animals. Pollen shows mostly herb/shrub tundra plants. The ocean along the coast was still full of life, with seals and productive kelp forests. These kelp forests might have attracted people traveling along the coast.

Environmental Changes During Ice Melt

Pollen data shows a warm period between 17,000 and 13,000 years ago, followed by a cooler time. Coastal areas quickly became ice-free as glaciers melted. This melting sped up as sea levels rose. The coast was fully ice-free between 16,000 and 15,000 years ago. Ocean life began to grow along the new shorelines. Coniferous forests started to replace the herb/shrub tundra by 15,000 years ago. Rising sea levels caused more flooding.

The huge ice sheets inland melted more slowly. The "ice-free corridor" didn't fully open until after 13,000 to 12,000 years ago. This corridor was initially filled with meltwater and ice-dammed lakes. It took a while for plants and animals to grow there. The earliest time it might have been possible for humans to use this route was around 11,500 years ago.

Birch forests began to grow in Beringia by 17,000 years ago as the climate improved. This shows the land was becoming more productive. Some studies suggest early humans might have used fire in Beringia as early as 34,000 years ago. They might have used fire to help hunt large animals.

When, Why, and From Where Did People Migrate?

Archaeological finds show that Indigenous peoples have been in the Americas for about 15,000 years. However, newer research suggests humans might have been here between 18,000 and 26,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum.

There are still some questions about the exact dates of ancient sites. Also, studies of modern Native American population genetics continue to provide new insights.

Timeline of Migration

In the early 2000s, there were two main ideas about when people migrated:

- The short chronology theory says the first migration happened after the Last Glacial Maximum, which ended around 19,000 years ago. Then, more groups followed.

- The long chronology theory suggests that the first people entered Beringia (including ice-free parts of Alaska) much earlier, possibly 40,000 years ago. A second wave of migrants came much later.

The Clovis First theory, which said Clovis people were the first, was very popular for a long time. But in the 2000s, archaeologists found sites in the Americas that were clearly older than 13,000 years. This challenged the Clovis First idea.

The oldest widely accepted archaeological sites in the Americas are about 15,000 years old. These include the Buttermilk Creek Complex in Texas, Meadowcroft Rockshelter in Pennsylvania, and Monte Verde in southern Chile. The Topper Site in South Carolina might be 16,000 years old, which was during the glacial maximum when coastlines were lower.

It was once thought that an ice-free corridor in what is now Western Canada allowed migration before the current warm period (Holocene). However, a 2016 study suggested this corridor was covered by forests. It concluded that Clovis people likely came from the south, perhaps following animals like bison.

Another idea is coastal migration. People might have traveled along the Pacific coast by boat after it became ice-free around 16,000 years ago.

Evidence for Humans Before the Last Glacial Maximum

New discoveries support the idea of migration across Beringia into the Americas before the Last Glacial Maximum. In 2021, human footprints were found in New Mexico's White Sands National Park. These footprints suggest people were there between 18,000 and 26,000 years ago. This age is based on dating seeds found in the same layers of earth.

Other sites, like Bluefish Caves and Old Crow Flats in the Yukon Territory, and Meadowcroft Rockshelter in Pennsylvania, also have possible pre-LGM dates. At Old Crow Flats, mammoth bones with signs of human butchery have been found, dating back 25,000 to 40,000 years. Stone tool fragments were also found.

However, some experts have questioned these findings, especially the butchery marks and how the bones were found.

In 2020, evidence from Chiquihuite cave in Mexico suggested human presence 26,000 years ago, based on stone tools.

In South America, the controversial Pedra Furada site in Brazil has evidence of controlled fire use from over 40,000 years ago. The fossil of Luzia Woman was once thought to be from a different group, but DNA tests in 2018 showed she was fully Amerindian.

The oldest confirmed artifacts at the Meadowcroft site are from after the LGM (13,800–18,500 years ago).

Stones found at the Cerutti Mastodon site in southern California might be tools used to process a mastodon skeleton. This skeleton was dated to 130,700 years ago. However, no human bones were found, and many experts doubt these claims.

The Yana River site in Siberia shows human activity 31,300 years ago. Some see this as proof that migration into Beringia was about to happen. But other evidence suggests that people in Siberia moved south as the climate got colder.

The oldest archaeological sites in Alaska are about 14,000 years old. It's possible a small group entered Beringia before then. But there aren't many human sites from closer to the LGM in either Siberia or Alaska. Biomarker studies from Alaskan lakes suggest humans were there as early as 34,000 years ago. These might be the only signs left of humans living in Alaska during the last Ice Age.

Clovis-first supporters still don't accept these older findings. They argue that if humans crossed the ice sheets much earlier, there should be clear sites with many artifacts. So far, they say, such evidence is missing.

DNA Age Estimates

Scientists study the DNA of modern Native Americans and Asian groups to understand their history. They look at specific DNA markers (haplogroups) to figure out when different groups branched off from each other.

One model suggests migration into Beringia happened between 30,000 and 25,000 years ago (Figure 2). Then, after 10,000 to 15,000 years of isolation, a small group moved into the Americas. Another model suggests migration into Beringia around 36,000 years ago, followed by 20,000 years of isolation there. A third model suggests migration into Beringia between 40,000 and 30,000 years ago, with some people moving into the Americas before the LGM.

Some studies have found a small amount of DNA from Australo-Melanesian people in Amazonian groups. This is still a mystery.

Tracing Megafauna Migrations

Besides human DNA, the DNA of large animals can help us trace early human movements. Early humans were often nomadic, meaning they moved around following their food sources. So, tracing animal movements can show us where humans might have gone.

Bison are a good example. Their DNA shows a "bottleneck" (a sharp drop in population) that can help test migration ideas. Unlike other large animals like mammoths and horses, bison survived the extinction event at the end of the Ice Age.

The grey wolf originally came from the Americas and moved into Eurasia before the Last Glacial Maximum. It was thought that wolves in North America were cut off during the LGM. But Radiocarbon dating of ancient wolf remains in Alaska shows that wolf populations kept moving between the two continents. This means there was a path open for them.

The ability of these animals to move between continents during the LGM, along with human genetic evidence, supports the idea of human migrations into the Americas even before the Clovis culture.

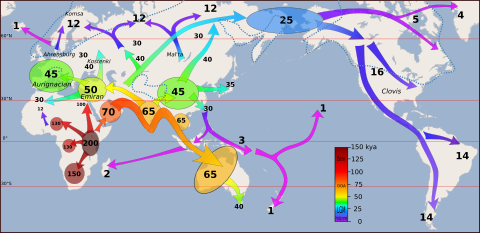

Where Did the First Americans Come From?

Most experts agree that the first people to migrate into the Americas came from an area east of the Yenisei River in Siberia. Specific DNA groups (Haplogroups A, B, C, D, and X) are common in both eastern Asian and Native American populations. The highest number of these groups is found in the Altai-Baikal region of southern Siberia.

A 2019 study suggested that Native Americans are closely related to 10,000-year-old fossils found near the Kolyma River in northeastern Siberia.

Human DNA Models

Advanced DNA analysis helps us understand Native American DNA groups even better. For example, the wide spread of haplogroup X once made some think of a European origin (the Solutrean hypothesis). But further study showed that a specific Native American haplogroup (X2a) is unique to them.

Scientists are constantly refining their search for the closest related groups in Asia. Some specific DNA groups found in Native Americans (like D1 and D4h3) were thought to be unique to them. But now, D1a has been found in the Ulchis of the lower Amur River region and in ancient Jōmon skeletons from Hokkaidō. This suggests a possible source population from that area, different from the Altai-Baikal region.

D4h3 has also been found in Han Chinese people. Its parent group, D4h, is thought to have appeared in East Asia, not Siberia. D4h3 is linked to coastal migration in the Americas. A 2022 study suggested that people from southern China might have contributed to the Native American gene pool, based on 14,000-year-old human fossils.

The differences between ancient Jōmon skeletons and modern Ainu show how tricky it is to use modern DNA to find original source populations. As more DNA results come in, and we better understand ancient populations, these models will become more accurate.

Physical Anthropology

Some very old human skeletons found in the Americas, like Kennewick Man and Luzia Woman, have skull shapes that look different from most modern Native Americans. This led some physical anthropologists to suggest a "Paleoamerican" population that came from a group similar to Australoid people, not Siberians. The main difference is the skull shape, which is longer and narrower. Some modern groups, like the Pericúes and Fuegians, also show this trait.

However, other anthropologists believe that the skull shapes changed over time. They suggest that the original Beringian people evolved, and then later, their features became more like modern Native Americans. Genetic studies do not support the idea of an Australoid origin. They strongly suggest that all Paleo-Indians and modern Native Americans came from one ancient population that migrated into the Americas. Only a very small amount (about 3%) of Australasian ancestry has been found in one ancient skeleton and a few modern Amazonian groups, which is still being studied.

A 2015 study looked at skull differences between early and later Native Americans. It noted that DNA studies mostly support a single migration from Asia, with a stop in Beringia. But skull studies sometimes suggest two entries into the Americas. A third idea, the "Recurrent Gene Flow" model, tries to combine these. It suggests that gene flow around the Arctic after the first migration could explain the changes in skull shape.

Stemmed Points (Tools)

Stemmed points are a type of stone tool that is different from tools found in Beringia and Clovis sites. They have been found from coastal East Asia all the way to the Pacific coast of South America. These tools first appeared in Korea during the Upper Paleolithic period. The presence and spread of stemmed points suggest a cultural link to a source population from coastal East Asia.

Migration Routes

The Inland Route

For a long time, the main idea was that people migrated from Beringia through the middle of North America. When artifacts were found with ancient animal remains near Clovis, New Mexico, in the 1930s, it showed that people were here when glaciers were still huge. This led to the idea of an ice-free path between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets.

The Clovis site had a special type of spear point with a groove, called a Clovis point. This type of tool was later found across much of North and South America. The Clovis First theory said that these big game hunters migrated out of Beringia and spread across the Americas.

New dating of Clovis sites shows they are from 13,000 to 12,600 years ago. This is a bit later than earlier estimates. Many Clovis sites have "problematic" dates and should be re-evaluated. Comparing Clovis dates with other sites and the opening of the ice-free corridor creates challenges for the Clovis First theory. For example, the Monte Verde site in Southern Chile is dated at 14,800 years ago. The Paisley Cave site in Oregon has human DNA and tools from 14,500 years ago. Other non-Clovis tools from before Clovis times have been found in eastern North America.

Geological findings also challenge the idea that Clovis people came through the ice-free corridor after the Last Glacial Maximum. The corridor might have closed around 30,000 years ago and only reopened between 12,000 and 13,000 years ago. Its earliest possible use for human migration is estimated at 11,500 years ago. This is later than the dates of Clovis and pre-Clovis sites. Dated Clovis sites suggest the Clovis culture spread from south to north.

Some suggest that people migrated into the interior before the LGM to explain the older pre-Clovis sites. However, sites like Meadowcroft Rock Shelter, Monte Verde, and Paisley Cave have not yet confirmed pre-LGM dates.

Dené–Yeniseian Language Family

Some linguists have suggested a link between the Na-Dene languages of North America (like Navajo) and the Yeniseian languages of Siberia. This idea, first proposed in 1923, has gained support from linguistic, archaeological, and genetic studies.

The Arctic small tool tradition in Alaska and the Canadian Arctic might have come from East Siberia about 5,000 years ago. This is linked to the ancient Paleo-Eskimo peoples.

The inland route fits with the spread of the Na-Dene language group and a specific DNA group (X2a) into the Americas after the earliest migrations. However, some scholars think the ancestors of western North Americans speaking Na-Dene languages might have traveled by boat along the coast.

The Pacific Coastal Route

The Pacific coastal migration theory suggests that people first reached the Americas by traveling along the coastlines from northeast Asia. This idea was first proposed in 1979 as an alternative to the inland corridor theory. This model helps explain how people could have quickly reached coastal sites far from the Bering Strait, like Monte Verde in southern Chile.

A similar idea, the marine migration hypothesis, says that boats were the main way people traveled. Using boats would mean that a continuous ice-free coast wasn't needed. Migrants could have bypassed ice barriers and settled in scattered coastal areas. This idea requires that the source population in coastal East Asia knew how to use boats.

A 2007 article proposed the "kelp highway hypothesis." This idea suggests that people followed kelp forests along the Pacific Rim, from Japan to Beringia, and all the way down to South America. Once the coasts of Alaska and British Columbia were ice-free (around 16,000 years ago), these kelp forests would have provided an easy, food-rich path at sea level. A 2016 DNA study of plants and animals supports the idea that a coastal route was possible.

A rare DNA group (D4h3a) found along the west coast of the Americas is linked to coastal migration. This DNA was found in a skeleton called Anzick-1 in Montana, found with Clovis artifacts and dated to 12,500 years ago.

Challenges with Coastal Migration Models

Coastal migration models offer a different view, but they have their own challenges. One big problem is that global sea levels have risen over 120 meters (400 feet) since the last Ice Age. This means the ancient coastlines that people might have followed are now underwater. Finding and digging up these submerged sites is very difficult and expensive.

To find these sites, scientists look for potential areas on submerged ancient shorelines. They also look for sites in areas that have been lifted up by Earth's movements or for river sites that might have attracted coastal migrants. There is evidence of ancient marine tools found in the Channel Islands of California from around 10,000 BCE. If there was an early coastal migration before Clovis, it's also possible that some attempts to settle failed.

|

See also

In Spanish: Poblamiento de América para niños

In Spanish: Poblamiento de América para niños

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |