White Sands National Park facts for kids

Quick facts for kids White Sands National Park |

|

|---|---|

|

IUCN Category V (Protected Landscape/Seascape)

|

|

Aerial view of dunefield

|

|

| Location | Otero County and Doña Ana County, New Mexico, United States |

| Nearest city | Alamogordo, New Mexico |

| Area | 145,762 acres (227.753 sq mi; 589.88 km2)+ |

| Established | January 18, 1933 (as a national monument) December 20, 2019 (as a national park) |

| Visitors | 729,096 (in 2023) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

|

White Sands National Monument Historic District

|

|

|

Former U.S. National Monument

|

|

Visitor center

|

|

| Built | 1936–38 (original NRHP buildings) |

|---|---|

| Architect | Lyle E. Bennett, et al. |

| Architectural style | Pueblo Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 88000751 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 23, 1988 |

White Sands National Park is a special place in New Mexico, USA. It is famous for its huge field of white sand dunes. These dunes are made of gypsum crystals, which is a rare type of sand. In fact, it's the biggest gypsum dunefield on Earth!

The park covers a large area of about 145,762 acres (590 km2). This includes a big part of the Tularosa Basin. The dunes can be as tall as 60 feet (18 meters). There are about 4.5 billion tons of gypsum sand here.

Long ago, about 12,000 years ago, this area had big lakes and grasslands. As the weather got warmer, rain and snow melted. This water dissolved gypsum from the nearby mountains. The water carried the gypsum into the basin. When the lakes dried up, they left behind selenite crystals. Strong winds then broke these crystals into tiny pieces. These pieces became the white sand we see today. This process still happens, making more gypsum sand.

Many animals live in the park, including thousands of tiny creatures. Some animals here are white or off-white. This helps them blend in with the sand. At least 45 species live only in this park. Forty of these are types of moths.

People have lived in the Tularosa Basin for a very long time. Paleo-Indians were here 12,000 years ago. Today, farmers, ranchers, and miners live in the area.

White Sands became a National Monument on January 18, 1933. President Herbert Hoover made it official. Since 1941, the park has been surrounded by military bases. These are the White Sands Missile Range and Holloman Air Force Base. On December 20, 2019, it became a full national park. This was signed into law by President Donald Trump.

It is the most visited NPS site in New Mexico. About 600,000 people visit each year. The park has a road that goes into the dunes. There are also picnic spots, hiking trails, and places to go sledding on the sand. Park rangers lead tours and nature walks.

Contents

History of White Sands

Ancient People of the Dunes

Scientists found some of the oldest human footprints in North America at White Sands. These footprints are buried in gypsum soil. They are thought to be between 21,000 and 23,000 years old. This means people were here much earlier than once thought! Other footprints of giant Ice Age animals, like ground sloths and Columbian mammoths, were found nearby. These animal prints seem to be from the same time as the human prints.

The Paleo-Indians lived by a large lake called Lake Otero. This lake covered much of the Tularosa Basin. They used stone from the mountains to make sharp points for their spears. They hunted large animals like mammoths, camels, and bison. As the climate changed, Lake Otero dried up. The basin became a desert. The giant animals disappeared, leaving only their fossil footprints.

Later, the Archaic people came to the Tularosa Basin about 4,000 years ago. They used a tool called an atlatl to throw spears. They also started to grow plants for food. They lived in small villages to take care of their fields. You can still find old fire pits, called hearth mounds, in the dunes. These hearths are preserved because the gypsum sand turns into a type of plaster when heated.

The Jornada Mogollon people lived here around 200 CE. They made pottery and built permanent houses. They farmed the Tularosa Basin until about 1350 CE.

Over 700 years ago, Apache groups arrived in the Tularosa Basin. They were nomadic hunters and gatherers. They lived in temporary homes like wickiups and teepees. The Apaches protected their lands from new settlers. Famous Apache leaders like Victorio and Geronimo fought battles with the US Army. Eventually, the Apaches were moved to the Mescalero Apache Indian Reservation. Today, the Mescalero Apache still feel a strong connection to this land.

European Settlers and the Park's Beginning

Spanish settlers mostly avoided the Tularosa Basin at first. It had no reliable water and was Apache territory. When they did enter, they used trails to get salt from the salt pans. Salt was important for processing silver.

Later, American settlers tried to claim the land. There was a dispute over who owned the salt flats. In 1854, a man named James Magoffin tried to charge people for gathering salt. This led to a conflict where some people were hurt. The courts decided that the salt flats should be free for everyone to use.

The US Army explored this area in 1849. Hispanic families started farming communities in the basin in the 1860s. They mixed gypsum sand with water to make plaster for their adobe homes. The white color helped keep their houses cool.

In the 1880s, more rain brought grasslands back to the basin. This attracted ranchers with their cattle, sheep, and goats. Ranching became very important for about 60 years. The Lucero family ranched near a lake that now bears their name, Lake Lucero. The National Park Service later took over these lands. You can still see parts of the old Lucero ranch today.

At the start of the 1900s, people found oil, coal, and other minerals. Many tried to mine in the Tularosa Basin. A plaster plant was even built to use the gypsum from the dunes. But when White Sands became a national monument, the plant closed.

Becoming a National Monument and Park

The idea to protect the white sands started in 1898. A group from El Paso, Texas, wanted to create a national park. But their plan included hunting, which didn't fit the idea of preserving nature.

From 1912 to 1922, Senator Albert B. Fall tried to create a national park here. His plan included several different areas. But the director of the National Park Service thought the areas were too spread out. Also, some people worried about using Native American land. So, the plan failed.

In the 1920s, a businessman named Tom Charles helped promote the white sands. He worked to get a better road built to the dunes. He also pushed for the dunes to become a national park. He was advised that a national monument would be easier to achieve.

On January 18, 1933, President Hoover officially made White Sands a National Monument. Tom Charles became its first manager. The visitor center and other buildings were built between 1936 and 1938. These adobe buildings are now part of a historic district.

The park is completely surrounded by military bases. This means the park sometimes closes for a few hours during missile tests. This helps keep visitors safe.

In the 1970s, oryx (a type of antelope) were released on the nearby missile range for hunting. Some of these animals entered the park. They competed with native animals for food. In 1996, a long fence was built to keep the oryx out of the park.

In 2008, White Sands was considered for a World Heritage Site listing. Some people supported this, thinking it would bring more visitors. Others worried it might affect military operations nearby. The local county commission opposed the idea.

In May 2018, Senator Martin Heinrich introduced a bill to make White Sands a national park. Many local groups and officials supported this. Some county commissioners, however, were concerned about potential changes to filming rules or increased regulations.

On December 20, 2019, President Donald Trump signed the bill. White Sands officially became a national park. This also added more land to the park.

White Sands in Movies

White Sands has been a popular place for filming movies. Many westerns have been filmed here, like Four Faces West (1948) and Hang 'Em High (1968). Other movies include King Solomon's Mines (1950), The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), and Transformers (2007). The band Wye Oak also filmed a music video here.

Geography of White Sands

White Sands National Park is in southern New Mexico. It's about 15 miles (24 km) southwest of Alamogordo and 52 miles (84 km) northeast of Las Cruces. The park sits in the Tularosa Basin. The land here is between 3,887 feet (1,185 meters) and 4,116 feet (1,255 meters) high.

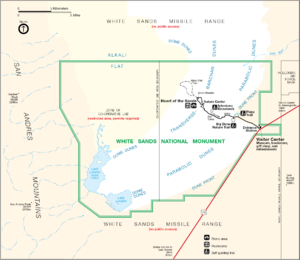

The main feature is the huge field of white sand dunes made of gypsum crystals. This is the largest gypsum dunefield in the world. The park protects about 115 square miles (298 km2) of this field. The rest of the dunefield is to the north, inside the White Sands Missile Range. The sand is about 30 feet (9 meters) deep. The tallest dunes are about 60 feet (18 meters) high. This amazing dunefield formed about 7,000–10,000 years ago.

The park covers about 148,588 acres (601 km2). In 2019, when it became a national park, more land was added. The missile range surrounds the park on all sides. Some areas on the western side of the park are called "cooperative use areas." You need a special permit to visit these parts. The San Andres Mountains are to the west. Holloman Air Force Base is a short distance to the east.

Climate at White Sands

White Sands National Park has a dry climate. It's often called a "cold semi-arid climate." This means it's dry, but not as hot as a true desert. The temperatures can change a lot between day and night.

The warmest months are from April to October. During this time, the average high temperature is often above 79°F (26°C). In June and July, afternoon temperatures can reach around 97°F (36°C). The hottest temperature ever recorded was 111°F (44°C) on June 22, 1981.

The cooler months are from November to March. The average low temperature is below 32°F (0°C). December and January are the coldest months. The lowest temperature ever recorded was -25°F (-32°C) on January 11, 1962.

The park gets about 9.81 inches (24.9 cm) of rain each year. August is usually the wettest month. Rain often falls from July to October. Snow can happen from November to March, but it's usually not much.

Geology of the White Dunes

Millions of years ago, shallow seas covered the area of White Sands. These seas left behind gypsum. Later, mountains formed, lifting some of this gypsum-rich land. Rain then dissolved the gypsum from the mountains. Rivers carried it into the Tularosa Basin, which has no outlet to the sea. The water either soaked into the ground or formed shallow pools that dried up. This left behind gypsum crystals called selenite.

During the last ice age, a huge lake called Lake Otero covered much of the basin. It was about 1,600 square miles (4,144 km2) in size. When this lake dried, it left a large flat area of selenite crystals. This area is now called the Alkali Flat.

Lake Lucero is a dry lakebed in the park. Rain and snowmelt from the mountains fill it with water that has dissolved gypsum. When the water evaporates, small selenite crystals form. Strong winds and water break these crystals into tiny grains. These grains become the white gypsum sand that forms the dunes.

The ground in the Alkali Flat and near Lake Lucero is covered with selenite crystals. Some can be up to 3 feet (1 meter) long! Over time, these crystals break down into sand. The wind then carries this sand, forming the white dunes. The dunes are always changing shape and slowly moving. After it rains, the gypsum sand can dissolve and then harden. This makes the sand more solid and resistant to the wind.

Even with the moving sand, some plants survive. Some plants grow fast enough to avoid being buried. Others form a hard base around their roots to stay stable.

There are different types of dunes in White Sands. Some are dome dunes, others are transverse or barchan dunes. Scientists use lasers and satellites to study the dunes. They look at the water below the dunes and how the sand grains are shaped.

The dunes on the western side are taller, over 50 feet (15 meters) high. They get smaller towards the eastern edge. The water underground is only a few feet from the surface and is very salty. The dunes on the western side move quickly and have little plant life. The dunes on the eastern side move slowly and have more plants. Scientists have even found old lake shores hidden beneath the dunes.

Ecology of White Sands

White Sands National Park is home to many living things. There are over 600 tiny creatures (invertebrates), 300 plants, 250 birds, 50 mammals, 30 reptiles, seven amphibians, and one fish species. Many animals here are nocturnal, meaning they are active at night.

Some animals have adapted to the white sand by becoming lighter in color. This helps them hide from predators. Many of these white animals live only in this park. Examples include the Apache pocket mouse, the bleached earless lizard, and many types of moths.

Plants of the Dunes (Flora)

The plants at White Sands help hold the dunes in place. They also provide food and shelter for animals. Native Americans used many of these plants for food, cloth, and medicine.

Plants here must be very tough. They live in dry, salty soil. They can handle temperatures from below freezing to over 100°F (38°C). Many of them love the high salt levels.

Plants like the cane cholla and soaptree yucca store water. This helps them survive hot summers and dry winters. Desert grasses like alkali sacaton and Indian rice grass grow well in the salty soil. Their seeds are food for small animals like pocket mice and kangaroo rats.

Native Americans used the soaptree yucca in many ways. Its young flower stalks are full of vitamin C. Its leaves were used to make rope, mats, and baskets. The roots made soap for washing.

Other plants include skunkbush sumac, Rio Grande cottonwood, and claret cup cactus. The sumac's berries were used for drinks, and its branches for baskets. The cottonwood's buds and flowers are edible. The claret cup cactus has very sweet fruit.

Animals of the Dunes (Fauna)

Over 800 animal species live in the park. Many are nocturnal. Some animals have changed color over time to match the white sand. This helps them hide from predators. The Apache pocket mouse, bleached earless lizard, and several moth species are examples of these white animals.

Tiny creatures called Invertebrates make up the largest group, with over 600 species. These include different kinds of spiders, wasps, beetles, and moths. Some spiders you might find are the Apache jumping spider and the tarantula. Other insects include the white-lined sphinx moth and the tarantula hawk wasp. The Maricopa harvester ant has very strong venom.

As of November 2019, 246 species of birds have been seen here. These include wrens, mockingbirds, and ravens. Larger birds like roadrunners and raptors also live here. Some common birds are the mourning dove, turkey vulture, and Chihuahuan raven. Cactus wrens build their nests in cacti. Birds are usually seen near the visitor center or the edges of the dunes.

Most mammals in the Tularosa Basin stay in their dens during the hot day. They come out at night to hunt and find food. You might see their footprints in the sand. Carnivorans like coyotes, bobcats, and kit foxes live here. Rabbits include desert cottontails and black-tailed jackrabbits. Jackrabbits can run very fast, up to 40 mph (64 km/h). Rodents like porcupines and Merriam's kangaroo rats are also found. The pallid bat is often seen flying around the visitor center at night.

Among reptiles, common lizards include the bleached earless lizard and the little white whiptail. Common snakes are the coachwhip and the western diamondback rattlesnake. All rattlesnakes are venomous. The only turtle here is the desert box turtle.

Seven species of amphibians live in the park. These include three types of toads and three types of spadefoot toads. Spadefoot toads have a hard "spade" on their back feet. They use it to dig into the ground to stay moist and hide. One salamander species, the barred tiger salamander, also lives here.

The White Sands pupfish is the only type of fish found in the park. It lives only in the Tularosa Basin. These small fish have silver scales and dark eyes.

Ancient Life (Paleontology)

Before the last ice age ended about 12,000 years ago, the Tularosa Basin was very different. It had large lakes, streams, and grasslands. The weather was cooler and wetter than it is today. Lake Otero was one of the biggest lakes in the southwest.

Giant ice age mammals lived by the shores of Lake Otero. These included Columbian mammoths, ground sloths, ancient camels, dire wolves, lions, and saber-toothed cats. As they walked on the muddy shores, they left behind fossil footprints. These fragile tracks are uncovered by the wind and then slowly disappear.

Scientists have found many fossilized footprints of these ancient animals. They often gather around where old pools of water used to be. In the 2010s, footprints of a dire wolf were found. They were next to ancient seeds that were over 18,000 years old. Human footprints have also been found interacting with these Ice Age animals. One set of prints shows humans tracking sloths. These human footprints are very important. They show that people lived in North America much earlier than many thought.

Ancient Meat-Eaters (Carnivores)

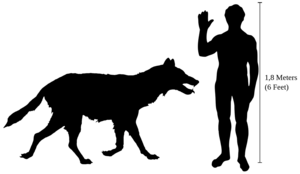

Dire wolfs lived in North and South America during the Ice Age. They were about the same size as modern gray wolves. But they were more muscular and had stronger jaws. They likely hunted in packs, going after large prey like horses and bison.

During the Ice Age, large cats like lions lived in North America. These lions were about four feet (1.2 meters) tall at the shoulder. They weighed over 500 pounds (230 kg). They had long legs for chasing prey. They hunted animals like deer, camels, and young mammoths.

Saber-toothed cats are famous for their huge canine teeth. These teeth could be seven to ten inches (17–20 cm) long! They were strong and muscular. They could take down big prey like sloths, bison, and young mammoths. Some evidence suggests they might have hunted in groups.

Ancient Plant-Eaters (Herbivores)

Columbian mammoths were enormous. They stood up to 14 feet (over four meters) tall at the shoulder. They weighed 18,000–22,000 pounds (8,000–10,000 kilograms). They had big tusks and ridged teeth for eating plants. Unlike woolly mammoths, they probably didn't have much hair.

Camels started in North America. The ancient western camel likely looked like modern, one-humped dromedary camels. But they had longer legs. They were opportunistic plant-eaters, grazing over wide areas.

Ground sloths are ancient relatives of modern tree sloths. The Harlan's ground sloth was huge. It could stand 10 feet (three meters) tall and weigh over a ton. These giant plant-eaters walked slowly. Their back feet rotated inward, leaving kidney-bean shaped footprints. Sometimes, their footprints looked like those of a giant human.

Visiting White Sands National Park

White Sands National Park is the most popular NPS site in New Mexico. About 600,000 people visit each year. Many visitors come in the warmer months, from March to August. But people also come year-round to sled and take photos. March and July are the busiest months.

The Dunes Drive goes 8 miles (13 km) into the dunes from the visitor center. There are three picnic areas. You can also camp overnight in the dunes at one of ten backcountry sites. Five marked trails, totaling 9 miles (14 km), let you explore the dunes on foot.

Park rangers lead tours and nature walks throughout the year. There are sunset strolls every evening. Lake Lucero hikes are offered once a month from November to April. Full moon guided hikes happen from April to October. The park also has a Junior Ranger Program with fun activities for kids.

Sometimes, the park and nearby U.S. Route 70 close for safety. This happens when tests are done at the White Sands Missile Range. The Dunes Drive might close for up to three hours. Park staff usually know about tests two weeks ahead of time. But sometimes, they get only 24 hours' notice. During these closures, all activities in the park are stopped. In 2020, visitors spent about $22.5 million in nearby towns. This helped the local communities.

See also

In Spanish: Parque nacional White Sands para niños

In Spanish: Parque nacional White Sands para niños

- List of national parks of the United States

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Otero County, New Mexico

- Trinity Site – where the first nuclear weapon was tested, at White Sands Missile Range

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |