Peter Jones (missionary) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Peter Jones

|

|

|---|---|

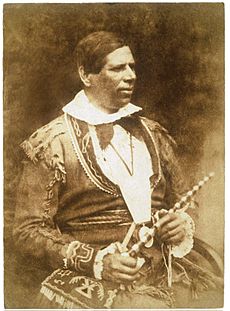

Portrait of Jones by William Crubb

|

|

| Born | January 1, 1802 |

| Died | June 29, 1856 (aged 54) |

| Resting place | Brantford, Ontario |

| Other names | Kahkewāquonāby Desagondensta |

| Spouse(s) | Eliza Field |

| Children | Five sons:

|

| Parent(s) | Augustus Jones Tuhbenahneequay |

| Signature | |

|

|

Peter Jones (born January 1, 1802 – died June 29, 1856) was an important leader for the Ojibwe people in Upper Canada (now Ontario). His Ojibwe name was Kahkewāquonāby, which means "Sacred Waving Feathers." He was also called Desagondensta in Mohawk, meaning "he stands people on their feet."

Peter Jones was a Methodist minister, a translator, a chief, and an author. He helped his people, the Mississaugas, survive and thrive during a challenging time. He acted as a bridge between the Indigenous communities and the European settlers.

Peter was raised by his mother, Tuhbenahneequay, learning the traditional ways of the Mississauga Ojibwe. When he was 14, he went to live with his father, Augustus Jones, who was of Welsh background. There, Peter learned English and the customs of the European settlers. He also learned how to farm.

At 21, Peter became a Methodist Christian. Church leaders saw that he could connect with both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. He became a preacher, translating hymns and Bible stories into Ojibwe and Mohawk. This helped many Mississaugas and Haudenosaunee people understand Christianity. Peter also traveled to the United States and Great Britain to raise money for the Canadian Methodists. He became very popular, drawing huge crowds.

Peter was also a strong political leader. In 1825, he wrote a letter to the British Indian Department. This was the first letter they had ever received from an Indigenous person. He worked with government officials to get support for the Credit Mission. This was a settlement where Mississaugas could live and learn European farming and Christian ways. In 1829, he was elected a chief of the Mississaugas of the Credit Mission. He spoke for his people to the government. He even met with King William IV and Queen Victoria in Britain. He asked Queen Victoria to give his people official land ownership documents, called "title deeds."

Although he faced many challenges, Peter helped the Mississaugas gain more control over their money. In 1847, he led his people to a new settlement called New Credit. This land was given to them by the Six Nations. The Mississaugas of New Credit still live on this land today. Peter's health declined, and he passed away in 1856.

Contents

Becoming a Minister

Finding His Faith

Peter Jones was drawn to the Methodist faith because it encouraged a different way of life. In June 1823, he went to a Methodist camp meeting with his half-sister Mary. This experience deeply affected Peter, and he decided to become a Christian.

A Methodist leader named Reverend William Case saw Peter's potential. He realized Peter could help bring the Christian message to the Mississauga people. Peter could speak both Ojibwe and English, and he understood both cultures. This made him perfect for connecting with both Indigenous and European Christian communities.

Soon after, a church group formed around Peter and Chief Thomas Davis. This group was made up entirely of Indigenous members. They encouraged other converted Indigenous people to settle near Davis's home. This area became known as "Davis' Hamlet." Peter and Seth Crawford taught Sunday school there. Many of Peter's relatives, including his mother, quickly joined the community.

In 1825, Peter received his first official church role as an "exhorter." This meant he could speak at services and help traveling preachers. Church leaders knew they needed someone fluent in Ojibwe to translate hymns and Bible stories. Peter was given the job of teaching at the Grand River mission. He also started speaking to groups about Methodism. By 1825, more than half of his community had become Christian. Peter decided to dedicate his life to missionary work.

The Credit Mission

In 1825, Peter Jones wrote a letter to the Indian Agent, James Givins. This was about the yearly gifts due to the Mississaugas from land agreements. It was the first letter Givins had ever received from an Indigenous person. Givins arranged a meeting with Peter. Peter arrived with about 50 Christian Indigenous people. His former adoptive father, Captain Jim, came with about 150 non-Christian Indigenous people. During this meeting, 50 more people from Peter's community converted to Christianity.

Givins was with important leaders, including Bishop John Strachan. They were impressed by Peter's group, especially their Christian clothes and their singing of hymns in Ojibwe. Even though Strachan was not a Methodist, he saw a chance to Christianize the Indigenous people through Peter. The government had promised to build a village for the Mississaugas on the Credit River in 1820, but nothing had happened. Strachan promised to fulfill this agreement.

Construction of the settlement, called the Credit Mission, began soon after. Peter moved there in 1826. By the summer of 1826, the rest of the community had joined the Methodist church and settled at the Credit Mission. Peter became good friends with Reverend Egerton Ryerson, who was assigned to the mission. This allowed Peter to travel more for missionary work. Between 1825 and 1827, Peter traveled to many areas, preaching in the native language. This helped small groups of Indigenous people convert to Christianity.

Peter's knowledge of English and his connections with important settlers helped him speak for his people. In 1825, he and his brother John asked the government to stop European settlers from fishing for salmon on the Credit River. This request was granted in 1829. In 1826, they returned to York because the Indian Department had not paid the full amount of money owed to their community from a land agreement.

At the Credit Mission, Peter also taught people how to farm. He believed that adopting Christianity and an agricultural lifestyle was vital for his people's survival. By 1827, each family had their own small farm plot. The success of the settlement and Peter's work made him well-known. His sermons were popular, and people donated money and goods to the community. In 1827, Peter received a special license to preach as a traveling minister.

Becoming a Chief

In 1829, the Mississaugas of the Credit Mission chose Peter Jones as one of their three chiefs. He replaced Chief John Cameron, who had recently passed away. Peter's ability to speak English and deal with missionaries and the government was a key reason for his election.

As chief, Peter continued his missionary work. He helped convert many Mississaugas at Rice Lake and the Muncey Mission. He also worked with Ojibwe people around Lake Simcoe and Lake Huron. Peter and his brother John also began translating the Bible into the Ojibwe language.

Travels to England

In 1829, Peter traveled to the northern United States with Reverend William Case to raise money for Methodist missions. They raised a lot of money. After returning, Peter was named "A Missionary to the Indian Tribes." In 1830, he was also ordained as a deacon.

By 1831, the Canadian Methodists needed more money. Peter traveled to the United Kingdom with George Ryerson. There, he gave over sixty sermons and one hundred speeches, raising more than £1000. He often wore his traditional Indigenous clothing during these speeches. This, along with his Indigenous name, made people very curious. Thousands of people came to hear him speak.

Peter met many important people in England, including Methodist leaders. He also met King William IV on April 5, 1832, shortly before returning to Canada. During this trip, he met Eliza Field, and they decided to marry. Eliza came to North America in 1833, and they married on September 8, 1833. Eliza came from a wealthy family, but she learned domestic skills to prepare for her new life. She worked with Peter at the Credit River settlement, teaching Indigenous girls sewing and other skills. The Mississaugas called Eliza "Kecheahgahmequa," meaning "the lady from beyond the waters."

Peter's translation of the Gospel of Matthew was published in 1832. He also helped edit his brother John's translation of the Gospel of John. On October 6, 1833, Peter was ordained as a minister in York, Upper Canada. He was the first Ojibwe person to become an ordained Methodist preacher.

Around this time, the Canadian Methodists joined with the British Wesleyans. This change meant that British leaders now ran the combined church. Peter sometimes felt overlooked for important positions, even though he was very skilled. He felt that his abilities were not fully recognized.

Fighting for Land Rights

In the mid-1830s, Lieutenant Governor Francis Bond Head wanted to move the Ojibwe people from the Credit River and other southern Upper Canada communities to Manitoulin Island. He believed Indigenous people needed to be completely separate from European settlers. Peter Jones strongly opposed this plan. He knew the soil on Manitoulin Island was poor, and moving there would force his people to stop farming and return to a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

After another land agreement, Peter became convinced that the only way to protect his people was to get official "title deeds" for their lands. These deeds would prove they owned the land forever. In 1837, Peter traveled to England again to speak directly with the Colonial Office. His wife and niece joined him.

Peter met with Lord Glenelg, the Colonial Secretary, in 1838. The meeting went very well. Glenelg promised to help Peter secure title deeds for the Mississaugas. Glenelg also arranged for Peter to meet Queen Victoria. Peter met her in September 1838. He presented a petition from the Mississauga Ojibwe chiefs, asking for title deeds to their lands. The petition was written in English and signed by the chiefs using their traditional pictographs. Peter, dressed in his Ojibwe regalia, explained the petition to Queen Victoria. She approved her minister's recommendation that the Mississaugas be given title deeds. Peter returned to Upper Canada shortly after.

Challenges and New Beginnings

When Peter returned to Upper Canada, some people in his community began to question his leadership. They felt he was making the Mississaugas too much like "Brown Englishmen." They worried about strict rules, the use of voting instead of traditional consensus, and the loss of Indigenous culture. By 1840, the Credit Mission faced many problems, including pressure from settlers and uncertainty about land ownership. The community council started thinking about moving.

Peter's influence with the government remained small despite his efforts. The Mississaugas of the Credit had been promised title deeds, but Peter's meeting with Lieutenant Governor George Arthur did not produce them. The Indian Agent, Samuel Jarvis, ignored the Mississaugas' concerns.

These community problems, along with Peter's new responsibilities as a father, made it harder for him to travel. His first son, Charles Augustus, was born in 1839. Peter and Eliza had previously experienced miscarriages and stillbirths, so they took great care in raising Charles.

In 1841, Peter was assigned to the Muncey Mission. This mission worked with three different Indigenous tribes, each speaking a different language. This made Peter's work challenging. Two more of his children were born here: John Frederick and Peter Edmund.

Peter's health began to worsen due to the stress of his work. In 1844, he was declared a "supernumerary" by the Methodist conference, meaning he was unable to perform all his duties due to ill health. The same year, the unhelpful Indian Agent Jarvis was removed from office. Peter was then able to meet with Lieutenant Governor Charles Metcalfe. Metcalfe was impressed by Peter. He provided money to build two schools at the Muncey Mission. He also gave the Credit Mississaugas control over their own money, making them the first Indigenous community in Canada to manage their own funds.

In 1845, Peter traveled to Great Britain for a third fundraising tour. He drew huge crowds, but he felt sad inside. He believed people came only to see him as an "exotic Indian" in his native costume, not for his Christian message. Despite his feelings, he raised £1000. During this trip, on August 4, 1845, Peter was photographed in Edinburgh by Robert Adamson and David Octavius Hill. These are the oldest surviving photographs of a North American Indian.

Moving to New Credit

When Peter returned to the Credit Mission, he believed the most important issue was getting clear ownership of their land. The settlement had successful farms and was becoming self-sufficient. However, the Indian Superintendent, Thomas G. Anderson, pressured the community to move. He wanted to group Indigenous people into larger settlements where schools could be better funded. He promised title deeds if they moved.

The Saugeen Ojibwa invited the Credit Mississaugas to move to the Bruce Peninsula. The Credit Mississaugas thought this was their best chance to get land deeds. They gave their Credit lands to the province. But a survey showed the Bruce Peninsula's soil was terrible for farming. Having given up their old land, the Mississaugas faced an uncertain future.

The Six Nations heard about their difficult situation. They remembered that the Mississaugas had given them land when the Six Nations first came to Upper Canada. So, the Six Nations offered a part of their own land to the Credit Mississaugas. In 1847, the Mississaugas moved to this new land along the Grand River. The settlement was named New Credit. Peter continued to be a community leader, asking the government for money to build the new settlement.

Peter's health continued to decline through the 1840s. By the time the Mississaugas moved to New Credit, he was too ill to move to an undeveloped settlement. He returned to Munceytown with his family. Peter resigned from his official position in the Methodist church but continued to work when his health allowed. In 1851, he moved to a new home near Brantford, which he called Echo Villa. This allowed him to be close to New Credit.

Even though his health was failing, Peter continued to work. He started woodcarving and won an award for his work. He also wrote for a publication called The Colonial Intelligencer; or, Aborigines' Friend. In the 1850s, Peter spent more time with his wife and children. His son Charles went to college and studied law. Peter still traveled when he could, visiting different places for missionary meetings and conventions.

The New Credit settlement faced some early challenges, but it soon began to do well. White settlers who had taken land illegally were eventually removed. Peter Jones became very ill in December 1855 and passed away at his home on June 29, 1856. He was buried in Brantford. After his death, his wife Eliza made sure his books were published. Life and Journals came out in 1860, and History of the Ojebway Indians in 1861.

Remembering Peter Jones

In 1857, a monument was built in Peter Jones's honor at New Credit. It reads: "Erected by the Ojibeway and other Indian tribes to their revered and beloved Chief Kahkewaquonaby (the Rev. Peter Jones)."

Inside the church at New Credit, built in 1852, there is a marble tablet that says:

In Memory of KAHKEWAQUONABY, (Peter Jones), THE FAITHFUL AND HEROIC OJIBEWAY MISSIONARY AND CHIEF: THE GUIDE, ADVISOR, AND BENEFACTOR OF HIS PEOPLE. Born January 1st, 1802. Died June 29th, 1856. HIS GOOD WORKS LIVE AFTER HIM, AND HIS MEMORY IS EMBALMED IN MANY GRATEFUL HEARTS.

In 1997, Peter Jones was recognized as a "Person of National Historic Significance" by the Canadian government. A celebration was held at New Credit to honor him and his role in helping the Mississaugas survive. The Ontario Archaeological and Historic Sites Board also put up a historical plaque at Echo Villa, where Peter lived before he died.

However, some descendants of the Mississaugan people have mixed feelings about Peter Jones. They see him as someone who fully adopted the settlers' ways of life.

Images for kids

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |