Iron Confederacy facts for kids

|

Nēhiyaw-Pwat ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐤ ᐸᐧᐟ

|

|

| Formation | unknown, before 1692 |

|---|---|

| Type | Confederation |

|

Membership

|

|

|

Official language

|

|

The Iron Confederacy was a strong group of Indigenous nations in what is now Western Canada and the northern United States. It was also known as the Cree-Assiniboine or Nēhiyaw-Pwat. This alliance brought together different groups like the Plains Cree, Assiniboine, Métis, Saulteaux, and Stoney. They worked together for hunting, trading, and protection against common enemies.

The Confederacy became very powerful during the North American fur trade. They acted as "middlemen," controlling how European goods (like guns) reached other Indigenous nations. They also controlled the flow of furs to the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) and North West Company (NWC) trading posts. Later, they played a big part in bison (buffalo) hunts and the pemmican trade. After the 1860s, the fur trade slowed down and the bison herds disappeared. This made the Confederacy weaker, and it could no longer stop the expansion of the U.S. and Canada.

Contents

How the Iron Confederacy Began

The Assiniboine people are thought to have come from the southern part of the Canadian Shield in what is now Minnesota. They became a separate group from their relatives, the Yanktonai Dakota, before 1640. At that time, they were called "rebels" by other Sioux speakers. By 1806, they were living in the Assiniboine River valley in Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

The Cree had contact with Europeans around 1611, when Henry Hudson arrived near Hudson Bay. Historians used to think that the Cree moved west and south to become traders for the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC). They would trade with other plains peoples, but only allowed the Assiniboine to access the HBC directly. However, new information from oral history and language studies suggests the Cree were already living west of Lake Winnipeg when the HBC arrived.

When the HBC opened its first trading posts in 1668 and 1688, the Cree became their main customers and traders. Before this, the Cree had only received old goods from the French trade system. With direct access to European tools and weapons, the Cree quickly expanded westward.

The earliest written records about the alliances west of Hudson's Bay come from Henry Kelsey's journal (around 1690–1692). He wrote that the Cree and Assiniboine were good friends with the Blackfoot. They were already allies against other groups, whose exact identities are not fully known today.

The history of the Stoney people before the mid-1700s is less clear. They speak a language called nakoda, which is similar to Assiniboine. Some believe Kelsey's journal might mention their ancestors. However, most agree they became a separate group from the Assiniboine around 1754–1755. At this time, Anthony Henday wrote about camping with "Stone" families near Red Deer, Alberta. The Stoney were already trading with the Cree and were military allies.

Growing Power and the Fur Trade

During the early 1700s, the Cree had conflicts with the Chipewyan to their northwest. With the help of a Chipewyan woman named Thanadelthur, the HBC helped make peace between the Cree and Chipewyan in 1715. By 1760, the Cree had expanded west to the Lesser Slave Lake area in northern Alberta. Here, they pushed out the Beaver people. These conflicts lasted until a smallpox epidemic in 1781 greatly reduced the Cree population. This led to a peace treaty at Peace Point, which gave its name to the Peace River. The river became the boundary between the Beavers and the Cree.

In the south, there are fewer records from this time. A Cree man named Saukamappee told David Thompson a story about the Cree helping the Piegan (Blackfoot) fight the Snake Indians around 1723. This battle was fought on foot with bows and arrows. By 1732, the Snakes had horses, which gave them an advantage. So, the Piegan asked the Cree and Assiniboine for help. This time, the Cree and Assiniboine used muskets (guns), which helped them win the battle. By 1750, it was noted that the Cree and Assiniboine were successfully raiding other groups.

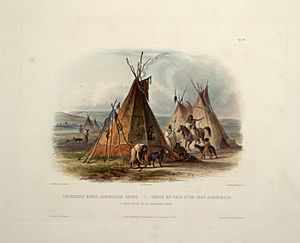

In 1754, Anthony Henday bought a horse from the Assiniboine near Battleford, Saskatchewan. He was the first European to see the Cree-Assiniboine trading with the Blackfoot. The trade was well-known: the Cree and Assiniboine traded European goods like guns, knives, and gunpowder to the Blackfoot. In return, they received horses, buffalo robes, and furs. The Blackfoot did not go to the HBC posts themselves because it was too far and they were not used to traveling by canoe. A gun was worth about 50 beaver pelts, and a horse was worth one gun.

Life on the Plains

As the HBC and NWC moved further west, the Iron Confederacy also moved to keep control of the trade. After 1760, the Cree were no longer just carrying furs. They found new opportunities supplying pemmican (dried bison meat) and other food to the fur traders. Some Cree, who traditionally lived in forests, began to live like plains people. They started hunting bison and riding horses. These new Plains Cree first allied with the Blackfoot, helping them push the Kootenay and Snake Indians across the Rocky Mountains. Many Assiniboine also moved west, and this led to the Nakoda (Stoney) people becoming a separate group around 1744.

The Confederacy fought many wars to control the trade of important goods on the plains. Before 1790, the Cree got horses from the Mandan people. They used these horses themselves and traded them to European fur posts. The Cree made good profits from trading with the Blackfoot. For example, a Cree trader might buy a musket for 14 beaver pelts and sell it to a Blackfoot warrior for 50. From the Mandan, they also got beans, corn, and tobacco in exchange for European goods.

By the mid-1800s, the Confederacy had lost control of the trade with the Mandan. From 1790 to 1810, they fought wars with their former horse suppliers to the south. The Gros Ventre people blocked the Confederacy from getting horses from the Arapaho. In 1790, the Gros Ventre joined the Blackfoot Confederacy, making the Iron Confederacy and the Blackfoot enemies. In response, the Plains Cree allied with the "Flathead" (Salish) Indians for new horses. The Battle River was named after a battle between the Cree and Blackfoot, who became long-term rivals. By the 1830s, mixed hunting groups of Cree, Assiniboine, and Métis reached Montana. The U.S. government even invited a Cree leader, Maskepetoon, to meet President Andrew Jackson in Washington D.C.

Many historical accounts of "the Cree" from this time actually refer to mixed groups of Cree, Assiniboine, and Saulteaux. Diseases like whooping cough (1819–1820) and smallpox (1780–1781) greatly reduced populations. This forced many bands to join with their neighbors.

By the 1850s, two groups, the "Cree-Assiniboine" and the Qu'Appelle, lived between Wood Mountain and the Cypress Hills. They traded on both sides of the international border.

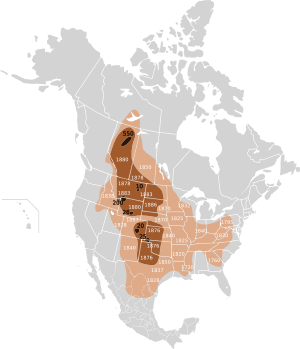

From about 1800 to 1850, the Iron Confederacy was at its strongest. They controlled trade with HBC posts like Fort Pitt and Fort Edmonton. Their expansion south peaked in the 1860s. At this time, the Plains Cree controlled most of southern Saskatchewan and east-central Alberta.

Decline of the Confederacy

Around 1850, the decline of the bison herds began to weaken the Iron Confederacy. Bison moved with the seasons, which often led to conflicts over hunting rights. Many plains peoples relied on the same herds. Overhunting by any group, including white settlers, affected everyone. The bison disappeared faster in the parkland areas where the Cree lived than in the southern prairies. The Cree blamed the HBC and Métis, but still needed them for trade. Bison could still be found in Blackfoot territories, which led Cree hunting groups to enter Blackfoot lands, causing more conflict. During these "buffalo wars," alliances changed, and the Iron Confederacy could not regain full access to the bison herds.

A story tells of a peace treaty between the Cree and Blackfoot at Wetaskiwin, Alberta, in 1867, but it did not last. Around 1870, the Gros Ventre left the Blackfoot Confederacy and allied with the Assiniboine. The Plains Cree fought one last major battle against the Blackfoot, the Battle of the Belly River, on October 25, 1870. They lost at least 200 warriors. After this, in 1873, Crowfoot, a Blackfoot leader, adopted Pitikwahanapiwiyin ("Poundmaker"), who was part Cree and part Assiniboine. This created a lasting peace between the Cree and Blackfoot.

In 1869, the Canadian government bought the HBC's land claims in western Canada. The Métis were upset because they were not consulted. They negotiated the Manitoba Act. However, the Métis could not get the Cree or Assiniboine to fully support their cause. The Wolseley expedition used military force to end the Red River Resistance.

By the 1870s, the disappearance of the buffalo caused a severe food crisis for the Confederacy's member groups. This forced them to seek help from the Canadian government. The government offered help in exchange for treaties that would end their land rights. The Iron Confederacy was always a loose group. When Canada negotiated treaties in the 1870s, they made agreements with individual bands, not with a central leader. Each band chose its own leader to sign the treaties.

Members of the Confederacy signed Treaty 1 (1871, southern Manitoba), Treaty 4 (1874–1877, southern Saskatchewan), Treaty 5 (1875–1879, northern Manitoba), and Treaty 6 (1876–1879, central Saskatchewan and Alberta). These were negotiated separately from Treaty 7 (1877) with the Blackfoot Confederacy. This showed that the Canadian government recognized the differences between the groups. Under these treaties, the Iron Confederacy bands accepted Canadian settlers on their lands. In return, they received emergency and ongoing aid to deal with the starvation caused by the disappearing bison. Not all bands agreed easily. Piapot's band signed a treaty but refused to choose a reserve site, preferring to remain nomadic. The "Battle River Crees" led by Big Bear and Little Pine refused to sign any treaty at all.

By 1878, the buffalo crisis was critical. Despite the treaties, little support came from the Canadian government. This forced more bands, both treaty and non-treaty, to hunt in Montana. By 1879 or 1880, the last buffalo disappeared from Canadian territory. Many Cree and Assiniboine bands moved south, often hunting in American territory or even living there year-round.

White settlers in Montana saw this as a threat. They feared that Indigenous groups from either side could attack Americans and then use Canada as a safe place. The United States began to build military forts in the region. In 1879, a Canadian report estimated that seven to eight thousand "British Indians" were hunting in Montana. This included famous leaders like Big Bear (Cree), Crowfoot (Blackfoot), and Louis Riel (Métis). Both the Canadian and U.S. governments wanted Indigenous people to stop their nomadic hunting and become farmers on reserves. This would open up the land for white settlers. Cree and Métis groups continued to hunt in Montana until late 1881. At that point, the U.S. Army began to arrest and deport them. This cut them off from one of the last bison populations, making them dependent on government food supplies.

The End of the Confederacy

In 1885, the Métis sought help for the North-West Rebellion. Many Cree and Assiniboine were unhappy with their situation. They felt the Canadian government was not keeping its treaty promises. However, deciding to fight was not easy. Different First Nations leaders had different views on the rebellion. Important war leaders like Big Bear and Poundmaker led their people into battle, even if they were reluctant. Others kept their people out of the conflict. This was one of the few times the Canadian government (after 1867) fought against First Nations peoples.

Initially, the Cree-Assiniboine alliance won the Battle of Cut Knife. However, Canada used its new railway and telegraph lines to quickly send militias from Ontario and Quebec to the West. These forces had more people, could move faster, and had better weapons. The Métis were defeated at Battle of Batoche, leaving the Cree-Assiniboine without allies. Poundmaker's mixed Cree-Assiniboine group surrendered. Three weeks later, Big Bear's band won a victory at Battle of Frenchman's Butte, but it was too late. The last group holding out (Big Bear and Wandering Spirit's) was scattered at Battle of Loon Lake on June 3, 1885.

After the rebellion, Big Bear and Poundmaker were briefly imprisoned. Wandering Spirit and six other Indigenous people were executed. A few members of Big Bear's band and other Cree sought safety in the United States. They were sent back to Canada, but most soon returned to the U.S. and settled on the Rocky Boy's Indian Reservation, where their descendants live today. Big Bear's son eventually returned to Canada and helped establish a reserve at Hobbema.

The disappearance of the buffalo, the treaties signed with the Queen, and the defeat in the North-West Rebellion all contributed to the Iron Confederacy losing its power as an economic, social, and independent group.

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |