Wolseley expedition facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Wolseley expedition |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Red River Rebellion | |||||||

Red River Expedition at Kakabeka Falls by Frances Anne Hopkins, 1877 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Garnet Wolseley | Louis Riel | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None | No immediate casualties; At least one later killed by militia |

||||||

The Wolseley expedition was a military journey in 1870. It was sent by Canadian Prime Minister John A. Macdonald to deal with Louis Riel and the Métis people during the Red River Rebellion. This happened at the Red River Colony, which is now part of Manitoba.

The expedition also aimed to stop American ideas of expanding into western Canada. The soldiers left Toronto in May and reached Fort Garry on August 24. After a tough three-month trip, they captured Fort Garry. This ended Riel's temporary government and helped secure western Canada for Canada.

Contents

Why Was the Wolseley Expedition Sent?

The Métis and the Canadian Government

Before the Wolseley Expedition, there were problems led by Louis Riel. The Métis people at Red River were unhappy with a land deal. The Canadian government had made a deal with the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) to take over Rupert's Land.

Riel was upset because the people at Red River were not told about a new governor. This new governor, William McDougall, was sent to take control.

Early Clashes and Riel's Government

The first big problem of the Red River Rebellion happened on October 11, 1869. Government land surveyors arrived at the Red River Settlement. A group of Métis soldiers stopped their work and made them leave.

After this, Riel stopped McDougall from entering Rupert's Land. Riel then took over Upper Fort Garry. He also set up a temporary government.

Prime Minister John A. Macdonald wanted to send a police force to Manitoba. He hoped this force would help control the Métis. This idea was later changed into the military expedition led by Garnet Wolseley.

Tensions Rise: The Thomas Scott Incident

In early 1870, Riel tried to negotiate with the government and the HBC. These talks did not go well. On March 4, 1870, a man named Thomas Scott was killed. Scott was a strong supporter of the Canadian government.

There are different ideas about why Scott was killed. Some say it was to make the Canadians negotiate seriously. Others say Riel simply disliked Scott. An eyewitness, Peter McArthur, said Scott was very vocal about his opinions. This might have angered Riel.

The Expedition's Difficult Journey

The expedition began in May 1870 from Toronto's New Fort York. It was led by Colonel Garnet Wolseley. Their goal was to reach Riel.

Before this, British and Canadian officials could travel through the United States to reach western Canada. However, the U.S. government refused to let British or Canadian troops cross their land. Many thought it was impossible to move a military force to Western Canada using only Canadian routes. The Dawson Road had only been mapped three years earlier, and a railway was still years away.

Building the Dawson Road

The Dawson Road was named after its designer, S.J. Dawson. He was hired to build a road wide enough for wagons pulled by horses. This road would stretch from Lake Superior to the rivers in the interior.

Dawson was supposed to finish the road by May 1, when the expedition would arrive. But bad weather, including rain and forest fires, delayed the work. Wolseley ordered soldiers to help build the road. They worked from May 25 until mid-July. Wolseley then made a new path from the road to the Winnipeg River.

Challenges on the Waterways

Another problem was getting lost in the Lake of the Woods. Wolseley and his boats were lost for several days. They finally found their way. Wolseley sent Indigenous paddlers back to help the other boats cross the lake. Despite these difficulties, the force reached Winnipeg in August.

The expedition traveled to Georgian Bay. Then they went by steamer across Lake Huron to the U.S. Sault Canal. Here, men and supplies had to be moved on the Canadian side of the river. The Canadian government hired two steamers, the Algoma and the Chicora.

The St. Mary's canal system went through U.S. territory. It was important for moving supplies north. The Algoma made it through, but the Chicora was stopped. American border agents stopped the steamers because they were moving soldiers and war supplies. They saw this as a threat.

The U.S. authorities made Wolseley unload all soldiers and war materials from the Chicora. Only then was it allowed to pass. Wolseley then arranged for the soldiers and materials to be carried 3 miles upriver on the Canadian side. They were then loaded back onto the waiting Algoma.

Reaching Fort Garry

The expedition then crossed Lake Superior to a public works station at Thunder Bay. Wolseley named this place Prince Arthur's Landing on May 25. He named it after Queen Victoria's third son.

From there, the troops carried small boats to Lake Shebandowan. On August 3, the first groups of canoes started their trip towards Fort Garry. They left from the shores of Shebandowan. The groups followed the old HBC fur trapping route. When they reached Kashabowie Lake, they took a new route that Dawson had found.

Traveling further west, they passed through Fort Frances, arriving on August 4. Wolseley reached Lake of the Woods but got lost. On August 15, he finally reached Rat Portage with his boats. He sent Iroquois guides back to help the other groups cross the river. They continued down the Winnipeg River and across Lake Winnipeg to the Red River. They finally arrived at Fort Garry in late August.

Capture of Fort Garry

Wolseley gathered his troops and immediately moved towards Upper Fort Garry. Eyewitness accounts say the fort's southern gate was open, and the fort was empty. Fort Garry was officially taken back by the Canadian government on August 24. The Union Jack flag was raised in a ceremony.

Louis Riel and his followers had left Fort Garry. This meant Wolseley's victory was "bloodless," meaning no fighting happened. The lack of resistance is thought to be because the location was so remote. Also, the government tried to avoid making the local people rebel more.

An eyewitness, William Perrin, wrote about the expedition's arrival. Perrin was a British soldier. His account appeared in the Manitoba Free Press in August 1900. This was 30 years after the event.

A Very Tough Journey

Military historians consider this expedition one of the hardest in history. Over 1000 men had to carry all their food and weapons, including cannons. They traveled hundreds of miles through the wilderness. At many places where they had to carry boats, they built temporary roads from logs.

While doing these jobs, the troops lived in the wilderness for over two months. They faced summer heat and many blackflies and mosquitoes.

Wolseley kept his British soldiers disciplined. However, the Canadian militiamen wanted to get revenge for Thomas Scott's death. The British soldiers soon returned to Ontario. This left the militia to guard the community. The militia's actions against the Métis made feelings worse, and at least one person was killed later.

Who Was Part of the Expedition?

British Military Forces

- 1st Battalion, 60th (The King's Royal Rifle Corps) Regiment of Foot: This was a battalion from the British Army. Colonel R.J. Feilden was in charge. He was second in command of the whole expedition. He led 26 officers and 350 men. These forces were called the 'Regulars'.

- Detachment of Royal Artillery: Lieutenant Alleyne led this group. It included 19 soldiers with four small cannons.

- Detachment of Royal Engineers: Lieutenant Hencage led these 19 engineers. Their main job was to help build the Dawson Road for the main expedition.

- Detachment of Army Service Corps

- Detachment of Army Hospital Corps

Canadian Militia

- 1st (Ontario) Rifles: This was a group of volunteer soldiers from Ontario. People in Ontario were eager to march to the Red River Colony because Thomas Scott, who was from Ontario, had died. Lieutenant-Colonel Jarvis led 28 officers and 350 volunteer soldiers.

- 2nd (Quebec) Rifles: This battalion was from Quebec. Reports from that time say there was little interest in Quebec for the expedition. At first, only 88 out of 350 soldiers in the battalion spoke French. The rest were English speakers. Lieutenant-Colonel Casault led this battalion with his 28 officers.

Transportation Workers

The expedition needed voyageurs and teamsters for transport. Over 400 Indigenous voyageurs were hired to handle the canoes. Reports say that 100 Iroquois voyageurs from Montreal were the most reliable. They were best at handling fast-moving water.

Besides boats, 150 horses and 100 teamsters were hired. Teamsters are people who handle horses and wagons. These men mainly transported supplies and people from Thunder Bay to Shebandowan Lake along the Dawson Road.

The North-West Mounted Police, which was created three years later in 1873, did not take part in this expedition.

What Was the Expedition's Impact?

After the expedition was successfully completed, Wolseley wrote a special message. He praised his men for their amazing efforts.

The expedition could not sail through the Soo Locks on the U.S. side of the river. This led the Canadian government to build a water passage on the Ontario side. This resulted in the building of the Sault Ste. Marie Canal, finished in 1895. That canal is now used for recreational boating. It is part of the national park system and is a National Historic Site managed by Parks Canada.

The Red River Expedition of 1870 was named a National Historic Event on January 12, 2018.

A street next to where Wolseley landed in Thunder Bay is named Wolseley Street.

Images for kids

-

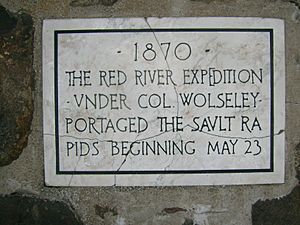

Cairn in Sault Ste. Marie commemorating the Wolseley Expedition's portage around the St. Marys Rapids.

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |