Treaty of Old Crossing facts for kids

The Treaty of Old Crossing (1863) and the Treaty of Old Crossing (1864) were important agreements between the United States and two groups of the Ojibwe people: the Pembina and Red Lake bands. These treaties involved the Ojibwe giving up their rights to a large area of land called the Red River Valley.

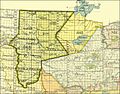

This land was located in what is now Minnesota and North Dakota. On the Minnesota side, it included lands west of a line from the Lake of the Woods to Thief Lake, then southeast to the Wild Rice River. On the North Dakota side, it covered the Red River Valley north of the Sheyenne River. This huge area, about 11 million acres, was rich with prairies and forests.

These agreements are known as the Old Crossing Treaty because the main talks happened at a place called "Old Crossing" on the Red Lake River. This spot, now known as Huot, was a common stopping point for Red River ox carts traveling between Pembina and places like Mendota and St Anthony.

Contents

Why the Treaties Happened

For a long time, the Ojibwe and Dakota (also called "Sioux") tribes had disagreements over hunting lands in the Red River Valley. However, the Ojibwe were the main group living there when European fur traders first arrived in the late 1700s. As trade grew between Pembina and St. Paul, people wanted to settle and develop the flat valley lands.

Even before Minnesota became a state in 1858, there was pressure to remove Native Americans from the Red River Valley. In 1849, U.S. Army Major Samuel Woods was sent to find a military post location and also to talk with the tribes. He was asked to see if their lands could be bought for white settlement. Major Woods met with Dakota, Ojibwe, and Métis people but didn't reach a land agreement.

Earlier Talks with the Ojibwe

In 1851, the Dakota gave up their claims to the Red River Valley in the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux and other Minnesota lands in the Treaty of Mendota. Soon after, the U.S. also tried to make a treaty with the Ojibwe at Pembina. The Red Lake and Pembina Ojibwe bands signed away rights to over 5 million acres of Red River Valley land.

However, the U.S. Senate did not approve this treaty. Some politicians were worried about new states joining the Union. So, the Ojibwe land deal failed at that time.

Throughout the 1850s, people continued to push for development in Northwest Minnesota. Steamboats started running on the Red River, and there were plans for railroads. Fur traders and others often entered Ojibwe territory. One trader even started a town called "Douglas" at the Old Crossing. The Ojibwe were unhappy about this town being built on their land. The county seat was later moved, but demands to deal with the Ojibwe land claims continued to grow.

After the American Civil War began, the U.S. renewed efforts to get the Red River Valley from the Ojibwe in 1862. Several Ojibwe chiefs were invited to talk. But then, the Dakota War of 1862 (also called the Sioux Uprising of 1862) spread to the Red River Valley. This forced the U.S. negotiators to leave. After the conflict, U.S. troops pushed the Dakota out of the valley. Traders and steamship operators again pushed politicians to get the land from the Ojibwe.

Alexander Ramsey and the Dakota Conflict

Alexander Ramsey was the main U.S. negotiator for the Old Crossing Treaties. He had been the first governor of Minnesota. After the "Sioux Outbreak," Ramsey became an Indian Commissioner in 1863.

When the Old Crossing treaty talks started again in 1863, settlers, soldiers, and politicians were still very worried from the Dakota Conflict of the previous summer. State and federal officials had started actions to remove the Dakota. Tensions were high between settlers and all Native American groups. There were rumors that the Dakota and Ojibwe might join forces.

Governor Ramsey had ordered strong actions against Dakota settlements in 1862. He famously said that the Dakota "must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of the state." After this, all treaties with the Dakota were canceled, and they were ordered to leave Minnesota.

In the spring and summer of 1863, Minnesota and U.S. forces were carrying out military actions against Dakota groups in the Red River Valley. Many of these actions happened close to the Old Crossing treaty site.

Before the Old Crossing Treaty, Commissioner Ramsey had already made several treaties with Ojibwe tribes across Minnesota. These treaties secured land for the U.S. in exchange for small payments and reservations. At the same time, Minnesota's new governor offered rewards for Native American scalps. Some people did not distinguish between Dakota and other tribes like the Ojibwe. Military groups also patrolled the Red River Valley. These actions were mainly against the Dakota, but they also aimed to intimidate the Ojibwe.

It was in this atmosphere of fear and pressure that Commissioner Ramsey tried again to get the Ojibwe lands in Northwest Minnesota for the United States. Ramsey had tried before in 1851 to get the Red River Valley from the Ojibwe. He had convinced the Red Lake and Pembina bands to sign a treaty that would have given up over 5 million acres for about five cents an acre. But that treaty was not approved.

The 1863 Treaty

When Alexander Ramsey arrived at the treaty site on September 21, 1863, he had a large group of 290 army men, many animals, and wagons. Soldiers set up a large gun pointed at the Ojibwe on the other side of the river. A day or two later, the Pembina band arrived, and talks began.

Ramsey first offered a small amount of $20,000 just for a "right of passage" through the land. The Ojibwe rejected this offer. Over several days, Ramsey tried to pressure the Ojibwe, who mostly did not want to sell their land. Finally, on October 2, 1863, Ramsey and another commissioner convinced the leaders of the Pembina and Red Lake bands to sign the Treaty of Old Crossing (1863).

The U.S. negotiators had made it seem like the treaty was only about allowing people to travel through Ojibwe lands. Ramsey told the Ojibwe that the U.S. did not really want their land. He said the U.S. only wanted its people to travel safely through their country on steamboats and wagons. He even suggested that if they sold the land, the Ojibwe could still live and hunt on it for a long time.

However, the actual treaty text said that the Ojibwe gave up all their control and ownership of the territory to the United States. In return, the Ojibwe bands would receive $20,000 per year for twenty years. The treaty also set aside $100,000 to pay claims from white people for past wrongs by Native Americans. It also gave the chiefs of two bands 640 acres of land each. Additionally, Métis (mixed-blood) relatives of the Ojibwe who were U.S. citizens could get "scrip," which allowed them to claim 160 acres of land.

1863 Treaty Signatories

| Affiliation | Title as Recorded | Name / Spelling in Treaty, (& English Translation) |

|---|---|---|

| Red Lake | Chief of Red Lake | Moozomoo / Mons-o-mo (Moose Dung) |

| Red Lake | Chief of Red Lake | Wawaashkinike / Kaw-wash-ke-ne-kay (Crooked Arm) |

| Red Lake | Chief of Red Lak(e) | Esiniwab / Ase-e-ne-wub (Little Rock) |

| Pembina | Chief of Pembina | Miskomakwa / Mis-co-muk-quoh (Red Bear) |

| Pembina | Chief of Pembina | Esens / Ase-anse (Little Shell) |

| Red Lake | Warrior of Red Lake | Miskokonaye / Mis-co-co-noy-a (Red Robe) |

| Red Lake | Warrior of Red Lake | Gichi-anishinaabe / Ka-che-un-ish-e-naw-bay (Big Indian) |

| Red Lake | Warrior of Red Lake | Niiyogiizhig / Neo-ki-zhick (Four Skies) |

| Pembina | Warrior of Pembina | Niibini-gwiingwa'aage / Nebene-quin-gwa-hawegaw (Summer Wolverine) |

| Pembina | Warrior of Pembina | Joseph Gornon |

| Pembina | Warrior of Pembina | Joseph Montreuil |

| Red Lake | Head Warrior of Red Lake | Mezhakiiyaash / May-shue-e-yaush (Dropping Wind) |

| Red Lake | Warrior of Red Lake | Min-du-wa-wing (Berry Hunter) |

| Red Lake | Chief of Red Lake | Naagaanigwanebi / Naw-gaun-a-gwan-abe (Leading Feather) |

"Signed in the Presence Of:"

| Affiliation | Title as Recorded | Name (& English Translation) |

|---|---|---|

| Unstated (Red Lake) | Special Interpreter | Paul H. Beaulieu |

| Unstated | None | Peter Roy |

| United States | United States Interpreter | T. A. Warren |

| United States (assumed) | Secretary | J. A. Wheelock |

| United States (assumed) | Secretary | Reuben Ottman |

| United States (Minnesota) | Major (Eighth Regiment Minnesota Volunteers) | George A. Camp |

| United States (Minnesota) | Captain Company K (Eighth Regiment Minnesota Volunteers) | William T. Rockwood |

| United States (Minnesota) | Captain Company L (First Regiment Minnesota Mounted Rangers) | P. B. Davy |

| United States (Minnesota) | Second Lieutenant (Third Minnesota Battery) | G. M. Dwelle |

| United States (Minnesota) | Surgeon (Eighth Regiment Minnesota Volunteers) | F. Rieger |

| United States (Minnesota) | First Lieutenant Company L (First Minnesota Mounted Rangers) | L. S. Kidder |

| Unstated | None | Sam B. Abbe |

| Unstated | None | C. A. Kuffer |

| Unstated (Red Lake) | None | Pierre x Bottineau |

Changes to the Treaty in 1864

After the 1863 treaty, some said the Ojibwe signers did not fully understand what they had agreed to. Bishop Henry Whipple even called it a "fraud." The main translator, Paul H. Beaulieu, may not have fully understood the Ojibwe language used by the Red Lake Band. Even if the translation was accurate, the treaty gave away over 10 million acres for about 5 cents an acre. Ramsey later boasted this was the lowest price ever paid for Native American land.

The U.S. Senate refused to approve the 1863 treaty, saying it was "too generous to the chiefs." They sent it back with changes. The Senate wanted any unused money from the $100,000 fund to go directly to all members of the bands, not just the chiefs. They also added a rule that the "half-breed scrip" could not be sold until after the land claim was fully proven.

Because of these changes, some of the original Ojibwe signers refused to sign the new version. However, the "treaty" was signed again by U.S. Commissioners and some Ojibwe representatives who had been taken to Washington, D.C., on April 12, 1864. President Abraham Lincoln then signed this version in May 1864.

The 1864 Supplemental Treaty

One of the unhappy Red Lake chiefs asked Bishop Whipple for help to improve the treaty benefits for the Ojibwe. This led to a second agreement, sometimes called the Treaty of Old Crossing (1864), which was negotiated in Washington, D.C. This supplemental treaty changed some things, making some benefits better but also ensuring that much of the money would not go to the tribes.

The 1864 supplement reduced the yearly payment from $20,000 to $15,000. It specifically gave $10,000 per year to the Red Lake band and $5,000 to the Pembina band. These payments would be given directly to individual members. The payments would continue as long as the President wished, not for a fixed 20 years. An extra $12,000 per year was added for 15 years, to be used for farming help and materials for clothing and other useful items. The U.S. also promised to provide a sawmill, a blacksmith, a doctor, a miller, and a farmer, along with tools. These changes meant the U.S. paid about 6 cents an acre for the land.

Other changes in the 1864 supplemental treaty caused arguments. The $100,000 fund was changed so that $25,000 would go immediately to the chiefs. The rest of the money was specifically for claims from Euro-American traders for goods taken by Native Americans or for payments demanded from steamboat operators. The decision on these claims was left entirely to the "agent for said bands," not a joint commission. This meant the white Indian agent controlled the money, and little of it went to the Native Americans themselves.

The 1864 supplemental treaty also changed the rules for "half-breed scrip." It limited claims to land within the ceded territory but removed rules about selling the scrip or proving up claims. The Red Lake Band has since said that the people who signed for them were not true leaders. They also argue that most of the Métis who benefited were not citizens and used the scrip to get timberlands that belonged to the Red Lake Band.

1864 Signatory Representatives

| Affiliation | Title as Recorded | Name / Spelling on Treaty, (& English Translation) |

|---|---|---|

| Red Lake | Principle Red Lake Chief | Medweganoonind / May-dwa-gua-no-nind (He That Is Spoken To) |

| Red Lake | Red Lake Chief | Moozomoo / Mons-o-mo (Moose Dung) |

| Red Lake | Red Lake Chief | Esiniwab / Ase-e-ne-wub (Little Rock) |

| Pembina | Principle Pembina Chief | Miskomakwa / Mis-co-muk-quah (Red Bear) |

| Red Lake | Red Lake Headman | Naagaanigwanebi / Naw-gon-e-gwo-nabe (Leading Wing-Feather) |

| Red Lake | Red Lake War[r]ior | Gwiiwizens / Que-we-zance (The Boy) |

| Red Lake | Red Lake Headman | Mezhakiiyaash / May-zha-ke-osh (Dropping Wind) |

| Red Lake | Red Lake Headman | Bwaanens / Bwa-ness (Little Sioux, recorded as "Little Shoe") |

| Red Lake | Red Lake Headman | Waabaanikweyaash / Wa-bon-e-qua-osh (White Hair[ed Wind]) |

| Pembina | Pembina Headman | Dibishko-giizhig / Te-bish-co-ge-shick (Equals the Sky, recorded as "Equal Sky") |

| Red Lake | Red Lake Warrior | Dibishko-bines / Te-besh-co-be-ness (Like a Bird, recorded as "Straight Bird") |

| Red Lake | Red Lake Warrior | "Osh-shay-o-sick" (No interpretation) |

| Red Lake | Red Lake Warrior | Zesegaakamigishkam / Sa-sa-goh-cum-ick-ish-cum (He That Makes the Ground Tremble) |

| Red Lake | Red Lake Warrior | "Kay-tush-ke-wub-e-tung" |

| Pembina | Pembina Warrior | Ayaanjigwanebi / I-inge-e-gaun-abe (Be Molting Feathers, recorded as "Wants Feathers") |

| Red Lake | Red Lake Warrior | Gwiiwizhenzhish / Que-we-zance-ish (Bad Boy) |

Legacy of the Treaties

Governor Ramsey later admitted that he had told the Ojibwe that the U.S. did not want their land for settlement. He said the U.S. only wanted a "free passage" through it. However, the treaty clearly stated that the Ojibwe "cede, sell, and convey to the United States all their right, title, and interest in and to all the lands." The U.S. goal was to end all Ojibwe claims to the land. This was stated in Ramsey's communications to others, but not to the Ojibwe during the talks.

Much of the money from the treaty's indemnity fund ended up with Norman Kittson. He was a businessman who ran steamboats on the Red River. The Ojibwe had accused Kittson of entering their territory without permission and causing problems. They had even demanded payment for the right to use the river. The treaty payments helped Kittson financially.

Even though the Ojibwe were not involved in the Dakota War of 1862, some white officials and newspapers linked them to the Dakota. They argued for fewer benefits for Native Americans because of the "Sioux Uprising." Some historians described the treaty as satisfying the Ojibwe who "wanted to sell their land." They also claimed the Ojibwe had "plundered" traders' property. Even in later years, the treaties were sometimes called "peace treaties." However, Ojibwe negotiators at Old Crossing had said they were not interested in selling their people's lands.

One Minnesota history book notes that while the treaties happened after the Dakota War, they were not a direct result of it. Plans for a treaty had been interrupted by the conflict.

Many people involved in the fur trade and early development of the region were connected. Norman Kittson, who benefited greatly from the treaty, had worked with others to develop towns on Ojibwe land. He and James J. Hill later built the first railroads through the Red River Valley.

Pierre Bottineau, a scout and interpreter, played a role in many of these events. He had guided expeditions and helped with earlier treaty talks. He also guided Ramsey during the 1863 Old Crossing Treaty negotiations and signed the treaty himself. After the treaty, Bottineau helped found towns like Red Lake Falls and Huot on the newly ceded Ojibwe lands.

Images for kids

See also

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |