Treaty of Traverse des Sioux facts for kids

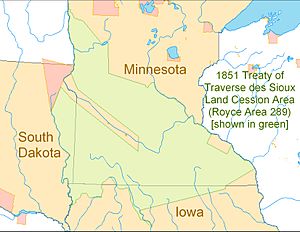

The Treaty of Traverse des Sioux was signed on July 23, 1851. It took place at a spot called Traverse des Sioux in what was then the Minnesota Territory. This important agreement was made between the United States government and the Upper Dakota Sioux groups. In this treaty, the Sisseton and Wahpeton Dakota bands sold a huge amount of land – about 21 million acres. This land is now part of Iowa, Minnesota, and South Dakota. The U.S. government paid them $1,665,000 for it.

The idea for this treaty came from Alexander Ramsey, who was the first governor of Minnesota Territory, and Luke Lea, a top official for Native American affairs in Washington, D.C.. They also had help from Henry Hastings Sibley, who represented the territory in Congress. Fur traders also pushed for the treaty because they wanted to get paid back for money they said the Dakota people owed them.

Governor Ramsey and Commissioner Lea told the United States Congress that the treaty was needed because many people were moving west. They said this "overwhelming tide of migration" was "increasing and irresistible." But really, they were also listening to land speculators. These were people who bought land hoping its price would go up. They wanted to encourage people to move to Minnesota instead of the newer states of Iowa and Wisconsin.

Contents

Why the Treaty Happened

In 1849, Governor Alexander Ramsey tried to buy land from the Dakota people, but he didn't succeed. He first offered less than three cents per acre, which wasn't enough to interest the Dakota leaders.

At that time, there was a big problem across the country. Money from past treaties had often gone to fur traders instead of directly to Native American families. Because of this, the United States Congress passed a law on March 3, 1847. This law said that in all future treaties, money and goods could only be paid to the heads of families or individuals. But Henry Hastings Sibley was still determined to get money for the traders.

Sibley told Governor Ramsey that he would not support any future land treaties unless the Dakota were "allowed" to pay off their "past debts." Ramsey soon realized that Sibley and other traders had a lot of influence with the Dakota. He knew he would have a better chance of success with their help.

By 1850, Ramsey and Sibley had reached an agreement. Governor Ramsey agreed to offer more money for the land, raising his offer from 2.5 cents to 10 cents per acre. He also agreed to find a way to get money for the traders and their "mixed-blood" (people of both Native American and European heritage) clerks and relatives. Sibley also encouraged Ramsey to replace the previous treaty commissioner, John Chambers, with someone who would be more open to these ideas.

Sibley then worked to build support for a new treaty. To convince the Dakotas, he told his traders to start giving credit and gifts freely again. This helped strengthen their family-like connections, even if it meant losing money in the short term. To win over the "mixed-blood" community, he promised to push for the sale of the Half-Breed Tract. This was a piece of land near Lake Pepin that had been given to them in the 1830 Treaty of Prairie du Chien. The land was mostly empty and owned by the community, but they couldn't sell it.

To get the missionaries on board, Sibley explained that selling a lot of land would make it impossible for the Dakota to hunt. This would force them to become farmers. He believed that if the Dakota owned individual farm plots instead of communal lands, they would become more "civilized" and more likely to accept Christianity.

A trader named Martin McLeod advised Sibley to talk to the Upper Dakota bands first – the Sisseton and Wahpetons. McLeod reported that after several hard winters, these western bands were very hungry and desperate for help. He was sure that "they would sign almost anything." The plan was that once the Upper Dakota signed a treaty, the Mdewakantons and Wahpekutes would surely follow.

A former fur trader named Joseph R. Brown asked his mixed-blood brother-in-law, Gabriel Renville, to help get support for the treaty among Sisseton and Wahpeton leaders. Historian Gary Clayton Anderson wrote that Renville likely believed he was helping his people out of a very difficult situation.

Treaty Discussions

On June 29, 1851, at 5:30 in the morning, the treaty officials left Fort Snelling. They traveled on a steamboat called the Excelsior. A large group went with them, including newspaper reporters, traders, and mixed-blood assistants connected to Henry Hastings Sibley. They arrived at Traverse des Sioux before noon the next day.

The Wahpeton and Sisseton bands of the Upper Dakota were not eager to give up so much land. However, older members of the tribes felt that what happened in the 1825 First Treaty of Prairie du Chien and the Black Hawk War meant they had limited choices.

What the Treaty Said

The Wahpeton and Sisseton bands gave up their lands in southern and western Minnesota Territory. They also gave up some lands in Iowa and Dakota Territory. In return, the United States promised to pay them $1,665,000 in cash and yearly payments.

Through the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux and another agreement called the Treaty of Mendota, the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute bands of the Lower Sioux gave up nearly 24 million acres of land. The U.S. paid the Dakota about 7.5 cents per acre each year. Meanwhile, settlers were charged $1.25 per acre to buy this land.

The U.S. government also set aside two reservations for the Sioux along the Minnesota River. Each was about 20 miles wide and 70 miles long. Later, the government said these reservations were only temporary. This was an attempt to force the Sioux out of Minnesota completely.

The Upper Sioux Agency was built near Granite Falls, Minnesota. The Lower Sioux Agency was built about 30 miles downstream near what is now Redwood Falls, Minnesota. The Upper Sioux were not happy with their reservation because there wasn't much food. But since it included some of their old villages, they agreed to stay. The Lower Sioux were moved away from their traditional woodlands. They were unhappy with their new territory, which was mostly open prairie.

The Sioux also disliked a separate "trader's paper" that was part of the treaty. This paper said that $400,000 of the promised treaty money would go to fur traders and mixed-blood people. These individuals claimed the tribes owed them money from past trades. The "trader's papers" listed the names of traders who were supposed to get money from the Dakota's treaty payments. The Dakota agreed to sign the main treaty and asked for a copy. After signing the copy, they were asked to sign a third paper. They believed this was just another copy. However, the Dakota were tricked into signing these "trader's papers" because the interpreters did not correctly explain what the document meant.

What Happened Next

Even with these problems, many settlers kept moving into the area. This meant more European-American people were moving onto Sioux land. The U.S. had promised more yearly payments if the Sioux gave up more land. So, Sioux leaders went to Washington, D.C., in 1858 to sign two more treaties. These treaties gave up the reservation land north of the Minnesota River.

The U.S. government wanted these treaties to encourage the Sioux to stop being nomadic hunters and gatherers. They wanted them to become farmers like the European-Americans. The government offered them money to help with this change. But this forced change in lifestyle and the much lower payments than expected from the government caused economic hardship. It also increased tensions within the tribes. These tensions eventually led to the Dakota War of 1862.

Treaty Details

The treaty begins by stating:

Articles of a treaty made and concluded at Traverse des Sioux, upon the Minnesota River, in the Territory of Minnesota, on the twenty-third day of July, eighteen hundred and fifty-one, between the United States of America, by Luke Lea, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, and Alexander Ramsey, governor and ex officio superintendent of Indian affairs in said Territory, commissioners duly appointed for that purpose, and See-see-toan and Wah-pay-toan bands of Dakota or Sioux Indians ...

—Treaty with the Sioux-Sisseton and Wahpeton Bands, 1851

Here are the main points of the treaty:

- Peace and friendship were to last forever.

- Land was to be given up.

- One section was removed by the U.S. Senate.

- Payments and other funds were to be held in trust.

- Laws against alcohol in Native American country were to be followed.

- Rules and regulations were set to protect the rights of people and property among the Native Americans.

One of the important signers was Sleepy Eye, from the Sisseton Sioux.

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |