British Band facts for kids

Quick facts for kids British Band |

|

|---|---|

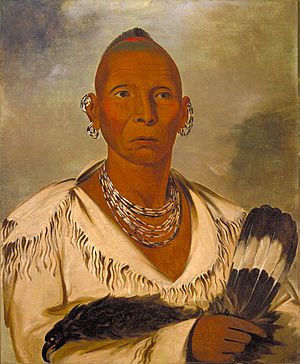

This 1854 artist rendering depicts members of the British Band at Stillman's Run.

|

|

| Leaders | Black Hawk |

| Dates of operation | 1831–1832 |

| Active regions | Illinois Michigan Territory |

| Size | ~500 warriors ~1,000 civilians |

| Allies | |

| Opponents | Illinois Militia, Michigan Territory Militia, United States Army |

The British Band was a group of Native American people. They were led by the Sauk leader Black Hawk. This group fought against the Illinois and Michigan Territory militias during the 1832 Black Hawk War.

The band had about 1,500 people in total. This included men, women, and children. They came from several nations like the Sauk, Meskwaki, Kickapoo, Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, and Ottawa. Around 500 of them were warriors, ready to fight.

Black Hawk had an old alliance with the British. This alliance started during the War of 1812. This is why his group was called the British Band. They crossed the Mississippi River from Iowa into Illinois. They wanted to get their homeland back. This action broke several peace agreements. Because of this, the Illinois and Michigan Territory militias were called to action. This started the Black Hawk War.

The British Band won an early battle at Stillman's Run. After that, there were not many big fights until the last two. These were the Wisconsin Heights and the Bad Axe River. Members of the band who survived the war were either held as prisoners or went back home. All prisoners were set free by Winfield Scott in August 1832. Black Hawk was the only one taken east. In 1833, he shared his life story. This became the first Native American autobiography published in the United States.

Contents

Why the War Started

Sauk warrior Black Hawk was a strong leader. He led a group of Sauks near Rock Island. Their home village was called Saukenuk. Black Hawk was against giving Native American lands to American settlers. He also disagreed with the U.S. government.

Black Hawk believed the Treaty of St. Louis was not valid. This treaty was made in 1804. It was between the Sauk and Fox nations and the U.S. government. The treaty gave away land, including Black Hawk's home village of Saukenuk.

The Sauk people usually made big decisions together. Everyone had to agree. But the people who signed the treaty did not have permission to give away land. They were only supposed to listen to the U.S. government's ideas. They were meant to bring these ideas back to the tribe for discussion. Since the tribe did not agree to the treaty beforehand, Black Hawk and others felt it was not valid.

Black Hawk and the War of 1812

During the War of 1812, the United Kingdom fought the United States. A British fur trader named Robert Dickson gathered many Native Americans. He wanted them to help the British near the Great Lakes. Most of these warriors were from the Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, Kickapoo, and Ottawa tribes.

Dickson gave Black Hawk a special military rank. He was made a brevet Brigadier General. This meant he was given command of all Native Americans gathered at Green Bay. This included 200 Sauk warriors under Black Hawk. Black Hawk also received a silk flag, a medal, and a paper. The paper said he was a good ally of the British. This paper and a similar flag were found 20 years later. They were found after the Battle of Bad Axe.

During the 1812 war, Black Hawk and his warriors fought in several battles. They fought with Henry Procter near Lake Erie. When Black Hawk returned home, his rival Keokuk had become the tribe's war chief. After the war, Black Hawk signed a peace treaty in May 1816. This treaty confirmed the 1804 treaty. Black Hawk later said he did not know about this part of the treaty.

Leading Up to the War

Black Hawk's group returned to Saukenuk in 1830. This was after their winter hunt. They came back even though Keokuk and U.S. officials told them not to. A year later, they returned again. The Illinois Governor, John Reynolds, called this an "invasion of the state."

Governor Reynolds asked for help. General Edmund Pendleton Gaines brought federal troops. They came from St. Louis, Missouri to Saukenuk. General Gaines told Black Hawk to leave right away. Black Hawk left but soon returned to the west side of the Mississippi. He was threatened by Gaines' troops. Governor Reynolds also called up 1,400 more militia members.

On June 30, Black Hawk and other leaders of the British Band had to sign an agreement. They promised to stay west of the Mississippi River.

Rumors of British Help

At the end of 1831, stories spread. People in the Upper Mississippi River Valley heard that the British would help Black Hawk. They believed the British would help if there was a war with American settlers. A newspaper in Galena reported that Black Hawk's band would get help and weapons from the British. Many people believed this story.

Major John Bliss, a military leader, heard these rumors. He told General Henry Atkinson. A follower of Keokuk also reported that Black Hawk and Neapope were talking with other tribes. These tribes included the Potawatomi, Kickapoo, and Ho-Chunk. The talks mentioned promises from the British. They also heard that French Canadians would help them.

These events, along with Black Hawk's alliance with the British in 1812, led to his group being called the British Band. This name was used by Americans, Sauk, and Fox people. It helped tell Black Hawk's group apart from other tribes.

The Black Hawk War Begins

The British Band had three main leaders. They were Black Hawk, the Ho-Chunk prophet Wabokieshiek (also called White Cloud), and Neapope. There were also seven other civil chiefs and five war captains. The band had about 500 warriors and 1,000 older people, women, and children. They crossed the Mississippi River on April 5.

The group included people from the Sauk, Fox, and Kickapoo Nations. They crossed the river near the Iowa River. Then they followed the Rock River northeast. They passed the old ruins of Saukenuk. Their goal was to reach the village of the Ho-Chunk prophet White Cloud.

As the war continued, some parts of other tribes joined Black Hawk. Others caused violence for their own reasons. For example, a group of Ho-Chunk attacked and killed a group led by Felix St. Vrain. This was known as the St. Vrain massacre. However, most Ho-Chunk helped the United States during the war. The warriors who attacked St. Vrain's group did not have permission from their nation. Some Potawatomi warriors also joined Black Hawk's Band between April and August.

First Fights and Skirmishes

When Black Hawk's Band crossed the Mississippi River in April 1832, they carried a British flag. Potawatomi Chief Shabbona said it was the same flag given to them in Canada. People at the time believed Black Hawk wanted to fight the United States. Many historians think the war could have been stopped. General Atkinson, who was in charge, could have stopped Black Hawk's Band from moving up the Rock River.

Governor Reynolds reacted to Black Hawk's movements. On April 16, he called up five groups of volunteers. They were to gather at Beardstown. Then they would go north to force Black Hawk out of Illinois. About one-third of all federal troops from the United States Army joined the fight. But most of the U.S. fighters were 9,000 soldiers from the Illinois Militia.

The first major fight of the Black Hawk War was on May 14, 1832. Black Hawk's Sauk and Fox warriors won an unexpected victory. They defeated the disorganized militia led by Isaiah Stillman. This fight was called the Battle of Stillman's Run. It happened near Stillman Valley. After this, exaggerated stories spread. People claimed 2,000 "bloodthirsty warriors" were destroying northern Illinois. This caused great fear.

After this first skirmish, Black Hawk led many civilians to the Michigan Territory. On May 19, the militia went up the Rock River. They were following Black Hawk and his band. Several small fights and attacks happened over the next month. These were in northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin. The militia then gained back public trust. They won battles at Horseshoe Bend and Waddams Grove.

Black Hawk himself led warriors in several battles. These included Stillman's Run, the Battle of Apple River Fort on June 24, and the Second Battle of Kellogg's Grove on June 25. He also led them in the final two battles: Wisconsin Heights and Bad Axe.

Some small fights and attacks after Stillman's Run were blamed on Native American groups not directly with Black Hawk. But many of these groups likely supported him or wanted to join him. For example, the events at Spafford Farm were blamed on a Kickapoo group. This group was loosely connected to the British Band.

After one attack, General Henry Atkinson learned that Henry Dodge would take over a military group. While Dodge was on his way, he heard a rifle shot from a group of Native Americans. Dodge quickly returned to his command post. He gathered as many men as he could to chase the enemy. Dodge chased them closely. A group of about 11 Native warriors crossed the Pecatonica River many times. They realized they could not escape. So, they prepared to fight at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend.

The battle at Horseshoe Bend and a small fight at Waddams Grove helped the Illinois Militia. These battles helped them regain public trust. This was important after the British Band's victory at Stillman's Run. The British Band attacked the Apple River Fort. A fierce battle was fought there. Black Hawk then pulled his forces back. Later fighting at Kellogg's Grove was called a victory for both sides. These fights resulted in 8 dead militia men and at least 15 dead British Band warriors.

The Final Battles

On July 21, 1832, Illinois and Wisconsin militia caught up with Black Hawk's British Band. This happened near Sauk City, Wisconsin. The fight became known as the Battle of Wisconsin Heights. This battle was very bad for Black Hawk's warriors. About 70 people died, including those who drowned. Even with many deaths, the battle allowed most of the Band to escape. Many women and children crossed the Wisconsin River to safety.

The militia gathered again at Fort Blue Mounds. They found Black Hawk's trail again on July 28. This was near Spring Green, Wisconsin. When they finally caught up with the British Band, it led to the last big battle of the war. This was at Bad Axe. At the mouth of the Bad Axe River, hundreds of men, women, and children were killed. They were killed by soldiers, their Native American allies, and a U.S. gunboat.

After the War

Many members of the British Band died during the war. This included people from the Fox, Kickapoo, Sauk, Ho-Chunk, and Potawatomi tribes. Some died fighting. Others were hunted down and killed by other tribes. These included the Sioux, Menominee, and Ho-Chunk. Still others died from hunger or drowned. This happened during their long journey up the Rock River.

The entire British Band was not wiped out at Bad Axe. Some survivors went back to their villages. This was easier for the Potawatomi and Ho-Chunk members. Many Sauk and Fox people found it harder to return home. Some returned safely, but others were held by the army.

About 120 prisoners were taken to Fort Armstrong. Some were captured at the Battle of Bad Axe. Others were taken by U.S.-allied Native American tribes in the weeks after. These prisoners, including men, women, and children, waited until the end of August. Then General Winfield Scott released them.

Most of the British Band was gone. Black Hawk was held prisoner at Jefferson Barracks. With him were Neapope, White Cloud, and eight other leaders. After 8 months, in April 1833, they were taken east. This was ordered by U.S. President Andrew Jackson. The men traveled by steamboat, carriage, and railroad. Large crowds met them everywhere they went.

In Washington, D.C., they met with President Jackson and Secretary of War Lewis Cass. Their final stop was a prison at Fortress Monroe in Virginia. They stayed there only a few weeks. During this time, they often posed for portraits by different artists. On June 5, 1833, the men were sent west by steamboat. They took a long route through many big cities. Again, people gathered in huge crowds to see them. This happened in cities like New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. However, the reaction in the west was very different. In Detroit, for example, a crowd burned and hanged effigies (dolls) of the prisoners.

Near the end of his time as a prisoner in 1833, Black Hawk told his life story. A government interpreter wrote it down. A local reporter then edited it. This became the first Native American autobiography published in the United States. The book was called Autobiography of Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak, or Black Hawk. It was published in 1882 in Oquawka, Illinois.

Images for kids