Mud March (American Civil War) facts for kids

The Mud March was a military plan during the American Civil War. It happened in January 1863. Union Army General Ambrose Burnside led this effort. He wanted to cross the Rappahannock River to attack the Confederate capital, Richmond, Virginia.

Burnside had tried to cross the river before and failed. This was his second attempt. The plan itself was good. But it failed because of bad weather and disagreements among his generals.

Contents

History of the Mud March

Burnside's New Plan

After losing badly at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, General Burnside wanted to improve his army's spirits. He also wanted to restore his own reputation. Right after Christmas, he started planning a new attack.

His idea was to trick the Confederates. He would make small attacks at river crossings upstream from Fredericksburg. Meanwhile, his main army would cross the Rappahannock River seven miles south of town.

Burnside also planned a huge cavalry (horse soldiers) operation. This was something new for the war in the East. Union horsemen had not done well against the Confederates so far.

The Cavalry Mission

Burnside chose 1,500 cavalry troopers for this mission. Five hundred of them would create a distraction near Warrenton and Culpeper. Then they would return to Falmouth.

The main cavalry force would cross at Kelly's Ford. They would then ride in a wide circle, going south and west. Their goal was to go all the way around Richmond. Finally, they would reach Suffolk on the coast. A Union force was already there. From Suffolk, ships would take them back to Falmouth.

It was a very creative plan. But it was doomed to fail.

A Secret Betrayal

The cavalry started their journey. But as soon as they reached Kelly's Ford, Burnside got a message. It was from President Abraham Lincoln. The message said, "No major army movements are to be made without first informing the White House." Burnside was confused. He had told almost no one about his plans. Even most of his high-ranking officers did not know.

Burnside had been betrayed by officers in his own army. These were Brigadier General John Newton and Brigadier General John Cochrane. They were commanders in the VI Corps.

The day after New Year's Day, these two generals took time off. They went to Washington D.C.. They wanted to meet with Senator Henry Wilson and Congressman Moses Odell. These men were important leaders of defense committees in Congress. But the generals forgot that Congress was on holiday. Neither representative was in town.

Meeting with Lincoln

Cochrane had been a congressman before the war. So he had political connections. He managed to get a meeting with Secretary of State William H. Seward. Seward then arranged for them to meet President Lincoln.

Newton, being the senior officer, spoke first. He told Lincoln that the Army of the Potomac was in very bad shape. He said it might fall apart if Burnside tried another attack. But he was vague and did not explain clearly. Later, Newton said he could not tell the president that the soldiers had no trust in General Burnside. But that was the main reason he came to Washington.

Lincoln thought they were just two officers trying to get their superior's job. He had seen this often. Cochrane promised they had no hidden reasons. They just wanted to inform the president. Newton then repeated his warning. He said the army would fall apart if Burnside lost another battle. The two generals left, suggesting Lincoln should look into things himself.

Burnside Confronts Lincoln

After getting Lincoln's message, Burnside went to the White House. He wanted to find out what happened. The president told him that two anonymous generals had revealed his plans. They also spoke about the army's poor condition.

Burnside was angry. He said these officers, whoever they were, should be punished. General-in-Chief Henry Halleck, who was there, agreed. Lincoln pointed out that there seemed to be a big problem between Burnside and his officers.

Burnside then asked to speak with the president alone. He complained about Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and General Halleck. He said it would be good for the country if both were replaced. He also added that none of his senior officers supported his plan for a winter attack. Finally, Burnside said he might resign from the army entirely.

After Burnside left, Lincoln told Halleck that Burnside's generals were not cooperating. He told Halleck to go to Fredericksburg and see the situation himself. Halleck had no advice for Burnside except to defeat the Confederate army with as little loss as possible. Lincoln also told Burnside to reconsider resigning.

The March Begins

Burnside changed his plan. Instead of crossing south of Fredericksburg, he decided to move upstream. He would cross at U.S. Ford, north of Chancellorsville.

The attack started on January 20, 1863. The weather was unusually mild. Burnside had a good start. He changed his plan again to aim for Banks' Ford. This was a closer and faster crossing.

At dawn on January 21, military engineers would build five bridges. Two large parts of the army would cross the river in four hours. Meanwhile, another part of the army would distract the Confederates. They would pretend to cross at Fredericksburg again.

The Storm Hits

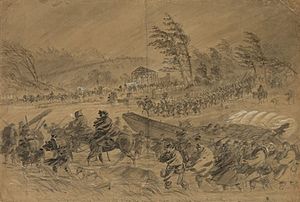

During the night of January 20, the rain began. By the morning of January 21, the ground was soaked. The river banks turned into a deep, sticky mud. Fifteen pontoon boats were already in the river, almost spanning it. Five more would have been enough.

Burnside immediately started bringing up his artillery (cannons). This made the mud even worse. For a large area around the ford, men worked all day in the rain. But they made little progress. Many cannons were moved near the ford.

January 22 brought even more storm. The artillery, their supply wagons, and even regular wagons got stuck in the mud.

The storm delayed Burnside's movements. This gave Lee plenty of time to line the other side of the river with his army. The Confederates did not try to stop the crossing much. Only sharpshooters fired occasionally. Lee probably hoped Burnside would cross. With a swollen river behind them, the Union Army would be in a terrible spot.

But Burnside finally accepted his fate. He ordered the army to return to their camps. This was the end of the famous Mud March.

The Mud March was Burnside's last attempt to command the Army of the Potomac. Lincoln replaced him with Major General Joseph Hooker on January 26, 1863.

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |