Knoxville campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Knoxville campaign |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||

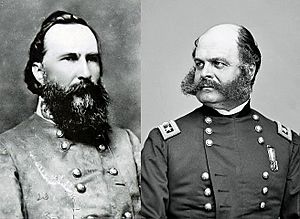

James Longstreet and Ambrose Burnside, important commanders in the Knoxville campaign |

|||

|

|||

| Belligerents | |||

| Commanders and leaders | |||

| Ambrose Burnside | James Longstreet | ||

| Units involved | |||

|

|

||

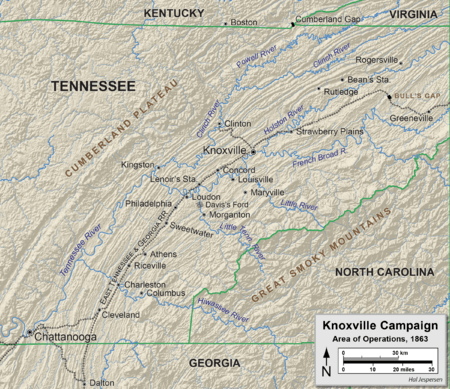

The Knoxville campaign was a series of battles during the American Civil War in the fall of 1863. It took place in East Tennessee. The main goal was to control the city of Knoxville. This city was important because it had a railroad that connected the eastern and western parts of the Confederacy.

Union Army forces, led by Major General Ambrose Burnside, moved into Knoxville. At the same time, Confederate States Army forces under Lieutenant General James Longstreet were sent from Chattanooga. Their job was to stop Burnside from sending help to Union troops who were surrounded in Chattanooga.

Longstreet tried to capture Knoxville, but he was not successful. The Union forces held the city. Eventually, Union Major General William Tecumseh Sherman arrived with more troops to help Burnside. Longstreet had to end his Siege of Knoxville and leave. Even though Longstreet was a very skilled commander, he could not break through Knoxville's defenses.

Contents

Why Knoxville Was Important

President Abraham Lincoln thought East Tennessee was a very important place to control. Most people in this mountainous region supported the Union. The area also had plenty of food, like grain and livestock. Plus, it controlled a key railroad that ran from Chattanooga to Virginia.

Throughout 1862 and 1863, Lincoln kept pushing his generals to move into this area. General Ambrose Burnside was given command of the Army of the Ohio in March 1863. He was ordered to capture Knoxville quickly. Meanwhile, another Union army, led by Major General William Rosecrans, was fighting Confederate General Braxton Bragg in Middle Tennessee.

Union Forces Advance

Burnside planned to move his two army corps, the IX Corps and XXIII Corps, from Cincinnati, Ohio. However, the IX Corps was sent to help Major General Ulysses S. Grant in the Vicksburg campaign. This caused a delay.

While waiting for the IX Corps to return, Burnside sent a smaller force to attack Knoxville. In mid-June, this group, led by Brigadier General William P. Sanders, destroyed railroads and disrupted communications around the city. At that time, Confederate Major General Simon Bolivar Buckner was in charge of East Tennessee.

By mid-August, Burnside began his main move toward Knoxville. The direct path through the Cumberland Gap was heavily defended by Confederates. So, Burnside decided to go around them. He sent one brigade to threaten the gap from the north. His other two divisions marched about 40 miles (64 km) to the south, over tough mountain roads, toward Knoxville. Even with bad roads, his soldiers marched up to 30 miles (48 km) a day.

Burnside's march started on August 16, 1863, from Lexington, Kentucky. About 18,000 troops from the XXIII Corps took part. The IX Corps, after returning from Vicksburg, was too sick to fight. They were used to guard the supply lines instead.

As the Chickamauga campaign began, Buckner was ordered south to Chattanooga. This left only a small Confederate force in the Cumberland Gap and another east of Knoxville. Burnside's cavalry reached Knoxville on September 2, facing almost no resistance. The next day, Burnside and his main army entered the city. The local people, who supported the Union, welcomed them warmly.

Capturing Cumberland Gap

In the Cumberland Gap, about 2,300 inexperienced Confederate soldiers were led by Brigadier General John W. Frazer. They had built defenses but had no clear orders after Buckner left. On September 7, Frazer was surrounded by Union forces from the north and south. He refused to surrender at first.

Burnside himself left Knoxville and marched 60 miles (97 km) in just 52 hours to join the fight. Realizing he was greatly outnumbered, Frazer finally surrendered on September 9.

Burnside then sent some cavalry to help Rosecrans. He also prepared to clear the roads from East Tennessee to Virginia. Washington, D.C., kept asking Burnside to move south and help Rosecrans. But Burnside did not want to give up the territory he had just captured. He also had trouble getting supplies through the rough mountains. He worried that moving farther away from his supply base would cause serious problems.

Battles in East Tennessee

Battle of Blountville (September 22, 1863)

On September 22, Union Colonel John W. Foster and his cavalry attacked Confederate Colonel James E. Carter and his troops at Blountville. The battle lasted four hours. Foster shelled the town and moved around the Confederate side, forcing them to retreat.

Battle of Blue Springs (October 10)

Confederate Brigadier General John Stuart Williams wanted to cut off Union communication and supply lines. He aimed to capture Bull's Gap on the railroad. On October 3, he fought with Union cavalry led by Brigadier General Samuel P. Carter at Blue Springs. Carter pulled back, unsure of the enemy's strength.

The two sides skirmished for several days. On October 10, Carter attacked Blue Springs with more force. The battle started around 10:00 a.m. Union cavalry fought the Confederates. Another Union force tried to get behind the Rebels to cut off their retreat.

At 3:30 p.m., Union infantry attacked. They broke through the Confederate line, causing many casualties. The Confederates retreated after dark. Union forces chased them the next morning. Within days, Williams and his men had gone back to Virginia. This battle helped the Union gain more control in East Tennessee.

Battle of Philadelphia (October 20)

After the defeat at Blue Springs, the Confederates asked for help. General Bragg sent infantry and cavalry from his army. On October 19, these Confederate cavalry brigades attacked Union cavalry at Philadelphia, Tennessee. The Union troopers were badly beaten. They were caught between a frontal attack and a flanking move.

Union losses were 7 killed, 25 wounded, and 447 captured. Confederate losses were 15 killed, 82 wounded, and 70 captured. Union forces briefly recaptured Philadelphia the next day. But Burnside soon ordered his troops to pull back to the north bank of the Tennessee River, leaving Loudon.

Longstreet Moves Toward Knoxville

Confederate President Jefferson Davis ordered General James Longstreet to attack Burnside. This was because Burnside was winning battles and might send help to the Union army surrounded in Chattanooga. Longstreet's troops had just helped the Confederates win the Battle of Chickamauga in Georgia.

Longstreet did not like the order. He knew he would be outnumbered. He had about 10,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry. Burnside had 12,000 infantry and 8,500 cavalry. Longstreet argued that splitting the Confederate forces would make both armies weaker.

Longstreet's plan was to travel by train to Sweetwater, about halfway to Knoxville. But the journey was full of problems. Trains were late, and the engines were too weak for the mountain hills. Soldiers had to get off and walk beside the cars. Engineers ran out of wood for fuel, so men had to stop and tear down fences. It took eight days for Longstreet's men to travel 60 miles (97 km). When they arrived, there were no supplies waiting for them. The soldiers, who had come from Virginia, did not have enough food or warm clothes for the winter.

The Lincoln government became worried about Burnside. After weeks of telling him to leave Knoxville, they now ordered him to hold the city. Grant tried to send help from Chattanooga. But Burnside suggested that 5,000 of his men would move toward Longstreet. They would make contact and then slowly retreat to Knoxville. This would keep Longstreet from going back to Chattanooga to help Bragg. Grant agreed to this plan. On November 14, Longstreet built a bridge across the Tennessee River and began chasing Burnside.

On November 15, Confederate cavalry tried to take the high ground overlooking Knoxville. But Union cavalry and artillery stopped them. The Confederates had to give up and rejoin Longstreet's main force.

Key Battles of the Knoxville Campaign

Battle of Campbell's Station (November 16)

Longstreet and Burnside raced toward Campbell's Station. This was a small town where two important roads met. Burnside wanted to reach it first and get to safety in Knoxville. Longstreet wanted to hold the crossroads to stop Burnside and force him to fight outside his defenses.

Burnside's lead troops reached the crossroads first on a rainy November 16. Just 15 minutes later, Longstreet's Confederates arrived. Longstreet tried to attack both sides of the Union line at once. One Confederate division attacked so hard that the Union right side had to move back, but they held their ground. The other Confederate division did not attack effectively.

Burnside ordered his two divisions to retreat about three-quarters of a mile (1.2 km) to a ridge. They did this without confusion. The Confederates stopped their attack, and Burnside continued his retreat to Knoxville.

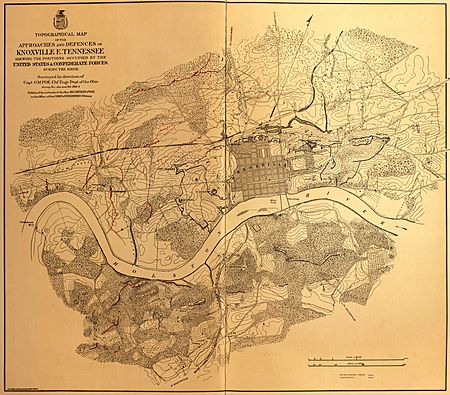

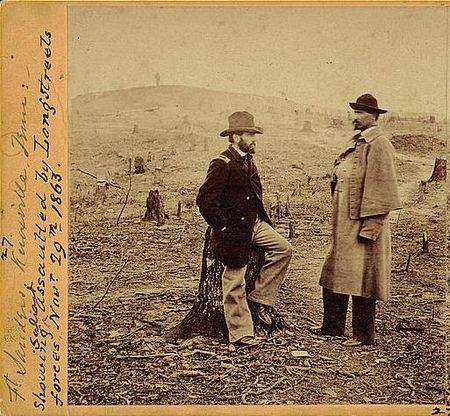

The Union retreat was well done. By November 17, most of Burnside's army was inside Knoxville's defenses. This began the Siege of Knoxville. The Confederates were not ready for a long siege and were running low on supplies. On November 18, William Sanders, the Union cavalry leader, was badly wounded in a skirmish and later died. Longstreet planned an attack for November 20 but delayed, waiting for more troops.

Battle of Kingston (November 24)

Longstreet worried that a small Union force at Kingston might cut off his supply lines. He sent Major General Joseph Wheeler with two cavalry divisions to destroy them. But when Wheeler's cavalry arrived, they found a strong Union force in a good defensive spot. After a small fight, the Confederate cavalry pulled back and rejoined Longstreet.

Battle of Fort Sanders (November 29)

Longstreet decided that Fort Sanders was the only weak spot in Knoxville's defenses. The fort was on a hill northwest of the city. Longstreet thought he could gather a surprise attack force at night below the fort. He hoped to capture Fort Sanders before dawn.

After a short artillery attack, three Confederate brigades charged. Union wire obstacles, made of telegraph wire stretched between tree stumps, slowed them down. But the fort's outer ditch stopped the Confederates completely. This ditch was 12 feet (3.7 m) wide and 4 to 10 feet (1.2-3 m) deep with straight sides. The fort's outer slope was also almost straight up.

Crossing the ditch was nearly impossible, especially with heavy Union gunfire. Confederate officers led their men into the ditch, but few made it out on the other side. The few who got into the fort were wounded, killed, or captured. The attack lasted only twenty minutes. It resulted in very unequal casualties: 813 Confederates compared to only 13 Union soldiers.

Battle of Walker's Ford (December 2)

About 6,000 Union troops, led by Brigadier General Orlando B. Willcox, stayed near Cumberland Gap. They protected the wagon road to the supply base in Kentucky. Willcox sent a cavalry brigade to Maynardville and moved his infantry to Tazewell.

Longstreet ordered Brigadier General William T. Martin to stop the Union cavalry. Martin's horsemen caught up with the Union brigade near the Clinch River. As the Union cavalry was pushed back, Willcox brought up two infantry regiments. They crossed the river at Walker's Ford and stopped Martin's cavalry. Another Confederate attempt to cross upstream was also blocked. Martin pulled his forces back toward Knoxville the next day.

Siege Ends

Longstreet learned that Bragg's army had been badly defeated at the Battle of Chattanooga on November 25. Longstreet was ordered to rejoin Bragg. But he felt it was not possible. He told Bragg he would take his troops back to Virginia. However, he would keep the siege on Knoxville going as long as he could. He hoped this would stop Burnside and Grant from joining forces.

This plan worked because Grant sent Sherman with 25,000 men to help Knoxville. Longstreet ended his siege on December 4. He retreated toward Rogersville, Tennessee, about 65 miles (105 km) northeast, to prepare for winter. Sherman left some troops in Knoxville and returned to Chattanooga with most of his army. Union forces followed Longstreet but did not attack too closely.

Battle of Bean's Station (December 14)

On December 13, Union Brigadier General James M. Shackelford was near Bean's Station. Longstreet decided to go back and capture Bean's Station. Three Confederate groups and artillery approached Bean's Station to trap the Union soldiers.

By 2:00 a.m. on December 14, one Confederate group was fighting Union guards. The guards held out and warned Shackelford. He prepared his forces for an attack. The battle began and lasted most of the day. Confederate attacks happened at different times and places. But the Union soldiers held their ground until more Southern troops arrived.

By nightfall, the Union forces were retreating from Bean's Station. Longstreet planned to attack them again the next morning. But when he reached them, they were well-defended. Longstreet pulled back, and the Union soldiers soon left the area.

What Happened Next

The Knoxville campaign ended after the Battle of Bean's Station. Both armies settled into winter camps. The main effect of this campaign was that it took away troops that Bragg badly needed in Chattanooga. Longstreet's time as an independent commander was not successful, and his confidence was hurt. He blamed others for the failure.

Burnside's good leadership during the campaign helped restore his military reputation. His successful defense of Knoxville, along with Grant's victory in Chattanooga, put much of East Tennessee under Union control for the rest of the war.

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |