Simon Bolivar Buckner facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Simon Bolivar Buckner

|

|

|---|---|

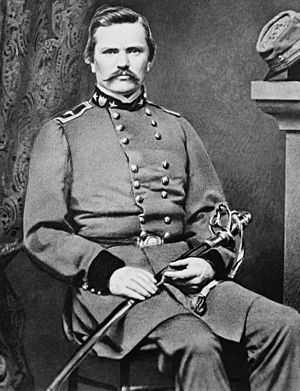

Buckner c. 1860–70

|

|

| 30th Governor of Kentucky | |

| In office August 30, 1887 – September 2, 1891 |

|

| Lieutenant | James Bryan |

| Preceded by | J. Proctor Knott |

| Succeeded by | John Brown |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 1, 1823 Munfordville, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | January 8, 1914 (aged 90) Hart County, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Resting place | Frankfort Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic National Democratic (1896) |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | Simon Jr. |

| Education | United States Military Academy (BS) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States Confederate States |

| Branch/service | United States Army Kentucky State Guard Confederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1844–1855 (U.S. Army) 1858–1861 (KY State Guard) 1861–1865 (C.S. Army) |

| Rank | Captain (U.S. Army) Major general (KY State Guard) Lieutenant general (C.S. Army) |

| Unit | U.S. 2nd Infantry Regiment U.S. 6th Infantry Regiment |

| Commands | Fort Donelson (Temporarily, surrendered) 2nd Division, 2nd Corps, Army of Tennessee District of the Gulf 3rd Corps, Army of Tennessee Department of East Tennessee District of Arkansas and Western Louisiana |

| Battles/wars | |

Simon Bolivar Buckner (April 1, 1823 – January 8, 1914) was an American soldier and politician. He fought in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War. Later, he joined the Confederate States Army in the American Civil War. After the war, he became the 30th governor of Kentucky.

After finishing his studies at the United States Military Academy, Buckner taught there. He left teaching to serve in the Mexican–American War. He resigned from the army in 1855 to manage his father-in-law's properties in Chicago, Illinois. In 1857, he returned to Kentucky. In 1861, Governor Beriah Magoffin made him adjutant general. In this role, he tried to keep Kentucky neutral at the start of the Civil War.

When Kentucky's neutrality ended, Buckner joined the Confederate Army. He had turned down a similar offer from the Union Army. In 1862, he surrendered at the Battle of Fort Donelson to Ulysses S. Grant. He was the first Confederate general to surrender an army in the war. He was a prisoner for five months. After his release, Buckner took part in Braxton Bragg's attempt to invade Kentucky. Near the end of the war, he became chief of staff for Edmund Kirby Smith.

After the war, Buckner became active in politics. He was elected governor of Kentucky in 1887. His time as governor saw conflicts in eastern Kentucky, like the Hatfield–McCoy feud. His administration also faced a scandal when the state treasurer took a large sum of money. As governor, Buckner was known for saying "no" to laws that favored special groups. In 1895, he tried to become a U.S. Senator but did not win. In 1896, he ran for vice President of the United States with the National Democratic Party. He did not win, getting only a small percentage of the votes. He never sought public office again and passed away on January 8, 1914.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Simon B. Buckner was born on April 1, 1823. His family's home, Glen Lily, was near Munfordville, Kentucky. He was the second son of Aylett Hartswell and Elizabeth Ann Buckner. He was named after Simón Bolívar, a famous South American leader. Buckner started school at age nine in Munfordville. His close friend there was Thomas J. Wood, who would become a Union Army general. They fought against each other in battles like Battle of Perryville and Battle of Chickamauga.

In 1838, his family moved to Muhlenberg County, Kentucky. His father, an iron worker, needed more wood for his furnace. Buckner went to school in Greenville, Kentucky and later in Hopkinsville, Kentucky. On July 1, 1840, Buckner began studying at the United States Military Academy. In 1844, he graduated eleventh in his class. He became a brevet second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Infantry Regiment. He was first stationed at Sackets Harbor, New York. Then, he returned to West Point to teach geography, history, and ethics.

Serving in the Mexican–American War

In May 1846, Buckner left his teaching job to fight in the Mexican–American War. He joined the 6th U.S. Infantry Regiment. He helped recruit soldiers and bring them to the Texas border. In November 1846, he joined his unit near Parras. His company then joined John E. Wool at Saltillo. In January 1847, Buckner's unit went to Vera Cruz. While Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott was attacking Vera Cruz, Buckner's unit fought Mexican cavalry nearby.

On August 8, 1847, Buckner became the quartermaster for the 6th Infantry. Soon after, he fought in battles at San Antonio and Churubusco. He was slightly hurt in the Churubusco battle. He was offered a promotion to first lieutenant for his bravery at Churubusco and Contreras. He accepted the promotion based on his actions at Churubusco.

Buckner was again recognized for his brave actions at the Battle of Molino del Rey. He was promoted to captain. He also fought in the Battle of Chapultepec, the Battle of Belen Gate, and the storming of Mexico City. After the war, American soldiers stayed in Mexico as an army of occupation. Buckner joined the Aztec Club of 1847. In April 1848, he was part of a successful trip up Popocatépetl, a volcano. Buckner had the honor of taking down the American flag over Mexico City for the last time.

Life Between Wars

After the war, Buckner was invited back to West Point to teach. He resigned a little over a year later. He did this to protest the academy's rule about mandatory church attendance. After leaving, he was assigned to a recruiting post at Fort Columbus.

Buckner married Mary Jane Kingsbury on May 2, 1850. Soon after, he was stationed at Fort Snelling and later at Fort Atkinson. On December 31, 1851, he became a first lieutenant. On November 3, 1852, he was made captain of the commissary department in New York City. Buckner was known for being fair with Native Americans. The Oglala Lakota tribe called him Young Chief. Their leader, Yellow Bear, would only negotiate with Buckner.

Before leaving the Army, Buckner helped his friend, Captain Ulysses S. Grant. He covered Grant's hotel costs until Grant received money to travel home. On March 26, 1855, Buckner left the Army. He went to work with his father-in-law, who owned a lot of property in Chicago, Illinois. When his father-in-law died in 1856, Buckner inherited the property. He moved to Chicago to manage it.

Buckner was still interested in military matters. He joined the Illinois State Militia of Cook County, Illinois as a major. On April 3, 1857, he was made adjutant general of Illinois by Governor William Henry Bissell. He resigned from this job in October of the same year.

In late 1857, Buckner and his family moved back to Kentucky. They settled in Louisville, Kentucky. His daughter, Lily, was born there in March 1858. Later that year, a Louisville militia called the Citizens' Guard was formed. Buckner became its captain. In 1860, he was appointed inspector general of Kentucky.

The Civil War Years

In 1861, Kentucky Governor Beriah Magoffin made Buckner adjutant general. He was promoted to major general. His job was to update the state's militia laws. Kentucky was divided between supporting the Union and the Confederacy. The state decided to stay neutral. Buckner gathered 61 companies to protect Kentucky's neutrality.

The state board that controlled the militia thought it was pro-secessionist. They ordered the militia to store its weapons. On July 20, 1861, Buckner resigned. He said he could not do his job because of the board's actions. In August, he was offered a general's rank in the Union Army twice. President Abraham Lincoln himself wanted him to join. But Buckner said no. After Confederate Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk took over Columbus, Kentucky, breaking Kentucky's neutrality, Buckner accepted a general's rank in the Confederate States Army on September 14, 1861. Many of the men he used to command followed him. When he joined the Confederacy, Union officials in Louisville accused him of disloyalty. They took his property. He became a commander in the Army of Central Kentucky.

Fort Donelson and Surrender

In February 1862, Union Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant captured Fort Henry. Grant then moved to Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. Confederate Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston sent Buckner to help defend Fort Donelson. Buckner was one of four generals there. The main commander was John B. Floyd. Buckner's fellow generals were Gideon J. Pillow and Bushrod Johnson.

Buckner's troops defended the right side of the Confederate lines around the fort. On February 14, the Confederate generals decided they could not hold the fort. They planned to break out and join Johnston's army in Nashville. The next morning, Pillow attacked Grant's army, pushing it back. Buckner, who did not trust Pillow, delayed his supporting attack for over two hours. This gave Grant's men time to get more soldiers and regroup. Even with the delay, the Confederate attack opened a path to escape. However, Floyd and Pillow ordered the troops back to their trenches.

That night, the generals held a meeting. Floyd and Pillow were happy with the day's fighting. But Buckner convinced them they had little chance to hold the fort or escape. Grant's army was getting more and more soldiers. General Floyd was worried he would be tried for disloyalty if captured. He asked Buckner to let him escape with some of his troops before the surrender. Buckner agreed. Floyd then offered command to Pillow, who refused and passed it to Buckner. Buckner agreed to stay and surrender. Floyd and Pillow escaped, as did cavalry commander Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest.

The next morning, Buckner sent a message to Grant. He asked for a ceasefire to discuss surrender terms. Buckner might have hoped for good terms, remembering how he helped Grant in the past. But Grant's reply was short and famous: "No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works." Buckner replied, accepting the "ungenerous and unchivalrous terms."

Despite the harsh words, Buckner greeted Grant warmly when he arrived. They joked about their time in Mexico. Grant offered to lend Buckner money for his time as a prisoner, but Buckner declined. Buckner had once paid for Grant's lodging when Grant was struggling. Later, Buckner was a pallbearer at Grant's funeral in 1885. He also helped Grant's widow financially. The surrender was a defeat for Buckner and the Confederacy. They lost over 12,000 men and control of the Cumberland River. This led to the evacuation of Nashville.

Kentucky Invasion and Later Service

While Buckner was a Union prisoner of war at Fort Warren in Boston, a Kentucky Senator tried to have him charged with disloyalty. On August 15, 1862, after five months, Buckner was exchanged for Union Brig. Gen. George A. McCall. The next day, he was promoted to major general. He was sent to Chattanooga, Tennessee, to join Gen. Braxton Bragg's army.

Soon after Buckner joined Bragg, both Bragg and Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith began to invade Kentucky. Bragg's first stop was Buckner's hometown of Munfordville. This town was important for Union forces. A small Union force under Col. John T. Wilder defended it. Wilder refused to surrender on September 12 and 14. By September 17, Wilder saw his difficult position. He asked Bragg for proof of his larger numbers. Wilder agreed to be blindfolded and taken to Buckner. He told Buckner he was not a military man and asked what he should do. Buckner showed Wilder the Confederate forces, which outnumbered Wilder's men almost 5 to 1. Seeing this, Wilder surrendered.

Bragg's men continued north to Bardstown to rest and get supplies. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell's Union army was moving toward Louisville. Bragg left his army and met Kirby Smith in Frankfort. He attended the inauguration of Confederate Governor Richard Hawes on October 4. Buckner also attended and gave speeches. The ceremony was interrupted by cannon fire from a Union division.

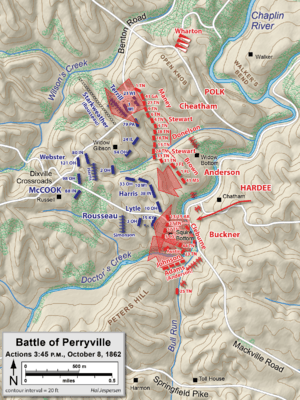

Buckner advised Bragg to attack Buell near Mackville before he reached Louisville. Bragg refused. Buckner then asked another general to convince Bragg to attack the Union army at Perryville. Again, Bragg refused. Finally, on October 8, 1862, Bragg's army fought Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook's corps. This started the Battle of Perryville. Buckner's division fought well, breaking through the Union line. Reports from his commanders praised Buckner's efforts. However, Perryville ended with no clear winner. Bragg decided to leave Kentucky. Buckner and many other generals criticized Bragg's actions during the campaign.

After Perryville, Buckner was sent to command the District of the Gulf. He strengthened defenses in Mobile, Alabama. In April 1863, he was ordered to command the Army of East Tennessee. He arrived in Knoxville on May 11, 1863. His department later became a part of Gen. Bragg's army.

In late August, Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside approached Knoxville. Buckner asked Bragg for more soldiers, but Bragg was busy fighting Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans. Bragg ordered Buckner to retreat. Buckner's unit then went to Ringgold, Georgia, then to Lafayette and Chickamauga. Bragg also retreated from Chattanooga and joined Buckner at Chickamauga. On September 19 and 20, the Confederate forces won the Battle of Chickamauga. Buckner's troops fought on the Confederate left side.

After Chickamauga, Rosecrans's army retreated to Chattanooga. Bragg held a siege but did not attack. Many of Bragg's officers, including Buckner, wanted Bragg removed from command. Bragg responded by reducing Buckner's command. Buckner took a medical leave and went to Virginia. His division went to support another general in the Knoxville campaign. Buckner briefly commanded Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood's division in February 1864. On March 8, he was given command of the Department of East Tennessee again. This department was much smaller and poorly equipped. Buckner was not very useful here. On April 28, he was ordered to join Edmund Kirby Smith.

Buckner had trouble traveling west. He arrived in early summer and took command of the District of West Louisiana on August 4. Smith soon asked for Buckner to be promoted. He became a lieutenant general on September 20. Smith put Buckner in charge of selling the department's cotton through enemy lines.

When news of Gen. Robert E. Lee's surrender reached the department, many soldiers left. On April 19, Smith combined two districts under Buckner's command. On May 9, Smith made Buckner his chief of staff. There were rumors that Smith and Buckner would not surrender. They were said to be planning to go to Mexico. Smith did cross the Rio Grande. But he learned that Buckner had gone to New Orleans on May 26 and arranged surrender terms. Smith had told Buckner to move all troops to Houston.

At Fort Donelson, Buckner was the first Confederate general to surrender an army. In New Orleans, he became the last to surrender a major force. The surrender became official when Smith approved it on June 2.

Life After the War

The terms of Buckner's surrender meant he could not return to Kentucky for three years. He stayed in New Orleans. He worked for a newspaper and a fire insurance company, becoming its president in 1867. His wife and daughter joined him in winter but returned to Kentucky in summer due to illnesses.

Buckner returned to Kentucky in 1868. He became editor of the Louisville Courier newspaper. Like many former Confederate officers, he asked the United States Congress to restore his civil rights. He got most of his property back through lawsuits. He also regained much of his wealth through smart business deals.

On January 5, 1874, Buckner's wife died after a long illness. Buckner continued to live in Louisville until 1877. Then, he and his daughter Lily returned to their family home, Glen Lily, in Munfordville. His sister also returned in 1877. For six years, they lived there and fixed up the house. On June 14, 1883, Lily Buckner married Morris B. Belknap and moved to Louisville. On October 10 of the same year, Buckner's sister died, leaving him alone.

On June 10, 1885, Buckner married Delia Claiborne of Richmond, Virginia. Buckner was 62, and Claiborne was 28. Their son, Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr., was born on July 18, 1886.

Images for kids

Error: no page names specified (help). In Spanish: Simon Bolivar Buckner para niños

In Spanish: Simon Bolivar Buckner para niños