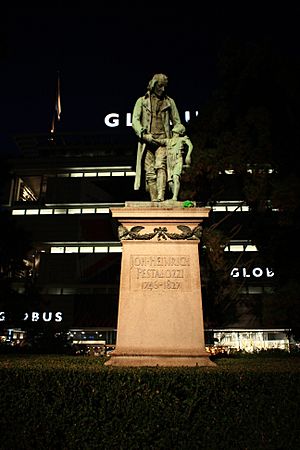

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi

|

|

|---|---|

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi by Francisco Javier Ramos, c.1806, Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid

|

|

| Born | 12 January 1746 Zürich, Switzerland

|

| Died | 17 February 1827 (aged 81) Brugg, Switzerland

|

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | German Romanticism |

|

Notable ideas

|

Four-sphere concept of life |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (German: [ˈjoːhan ˈhaɪnrɪç pɛstaˈlɔtsiː], Italian: [pestaˈlɔttsi]; 12 January 1746 – 17 February 1827) was a famous Swiss educator and reformer. He believed in a new way of teaching that was very much like the Romanticism movement.

Pestalozzi started many schools in Switzerland. He also wrote books about his new and exciting ideas for education. His main idea was "Learning by head, hand and heart." This means learning with your mind, by doing things, and with your feelings. Thanks to Pestalozzi, almost everyone in Switzerland could read and write by 1830.

Contents

- Pestalozzi's Life Story

- Pestalozzi's Big Ideas

- Pestalozzi's Lasting Impact

- See also

Pestalozzi's Life Story

Early Years (1746–1765)

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi was born in Zürich, Switzerland, on January 12, 1746. His father was a surgeon who passed away when Pestalozzi was only five years old. His mother, whose family came from Wädenswil, had to support three children. A kind maid named Barbara Schmid, or Babeli, helped the family a lot.

In 1761, Pestalozzi went to a school called the Gymnasium. He learned from teachers like Johann Jakob Bodmer, who taught history, and Johann Jakob Breitinger, who taught Greek.

During holidays, Pestalozzi visited his grandfather, who was a clergyman. They would visit schools and homes in the countryside. These visits showed Pestalozzi how poor many country people were. He saw how children had to work in factories at a young age. He also saw that the schools at the time didn't help them much. Seeing their struggles deeply affected Pestalozzi. This experience shaped his future ideas about education.

Pestalozzi first planned to become a clergyman. He thought this job would let him use his educational ideas. However, after a sermon didn't go well and he was inspired by philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, he decided to study law and justice instead.

Young Adulthood and Early Goals (1765–1767)

In the mid-1700s, the Swiss government didn't like Rousseau's books, Emile and Social Contract. They thought these books were dangerous. Pestalozzi's former teacher, Bodmer, liked Rousseau's ideas. In 1765, Bodmer started the Helvetic Society with other thinkers. Their goal was to promote freedom. Pestalozzi, then 19, was an active member. He wrote many articles for their newspaper, Der Erinnerer.

Pestalozzi wrote about some unfair actions by officials. He was even arrested for three days, though he was later found innocent. These events created many political enemies for him. This made it impossible for him to have a career in law.

Neuhof: A New Start (1769–1779)

After his political plans failed, Pestalozzi decided to become a farmer. He was inspired by Johann Rudolf Tschiffeli, who had turned poor land into successful farms. In 1767, Pestalozzi visited Tschiffeli to learn his methods. A year later, Pestalozzi bought 15 acres of unused land near Zürich. He got money from a banker and bought more land. In 1769, he married Anna Schulthess.

Pestalozzi built a house on his land, calling it "Neuhof." But the land was not good for farming. The banker stopped supporting him. To make more money, Pestalozzi added a wool-spinning business. But his problems and debts grew. Three months after losing financial support, his wife gave birth to their only son, Jean-Jacques. The boy, nicknamed Schaggeli, often had health problems, which worried his parents.

From Farm to School at Neuhof

When his farming failed, Pestalozzi wanted to help poor people. He had known poverty himself. He saw orphans who became apprentices but were overworked and hungry. He wanted to teach them how to live with dignity. This led him to turn Neuhof into an industrial school. Even though his wife's family disagreed, he got support from philosopher Isaak Iselin. Iselin wrote about Pestalozzi's idea, which helped him get donations and loans.

The new school seemed to do well at first. But after a year, Pestalozzi's old problems with money management caused trouble again. In 1777, he asked the public for help, which gave the school a temporary boost. He also wrote letters about educating the poor. However, the help was not enough. In 1779, Pestalozzi had to close Neuhof. With friends' help, he saved the house for his family. But they were still very poor. Many people who had been interested in his ideas left him.

A Time for Writing (1780–1797)

The Evening Hours of a Hermit (1780)

Iselin remained Pestalozzi's friend and encouraged him to keep writing. In 1780, Pestalozzi anonymously published a series of short sayings called The Evening Hours of a Hermit. These were his first writings that showed his unique educational ideas. Few people noticed them at the time.

Leonard and Gertrude (1781, 1783, 1785, 1787)

Pestalozzi knew the lives of country people very well. He used these experiences to write a four-volume story called Leonard and Gertrude. The story is about four main characters: Gertrude, Glüphi, a clergyman, and Arner. Gertrude is a mother who teaches her children good values through faith and love. Glüphi, a teacher, sees Gertrude's success and tries to teach his students in a similar way. A clergyman also uses Gertrude's methods. A politician named Arner helps them get support from the government. Through their efforts, everyone in the village gets a good education and lives in harmony.

The first volume was very popular. However, the other three volumes were not as widely read.

Enquiries into the Course of Nature in the Development of the Human Race (1797)

In 1794, Pestalozzi met famous writers like Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Johann Gottfried Herder. He also met Johann Gottlieb Fichte, a philosopher, who encouraged him to write about his ideas on human nature and how people develop. Three years later, Pestalozzi published Enquiries into the Course of Nature in the Development of the Human Race. However, very few people read this book. In 1821, Pestalozzi himself wrote that "Scarcely any one has noticed the book."

This book marked the end of 18 years where Pestalozzi and his family lived in poverty. His wife was often sick. In 1797, his son also returned home ill.

Stans: Helping Orphans (1799)

Big political changes were happening in Switzerland. In 1798, serfdom (a system where people were tied to the land) was ended. Pestalozzi decided to become a full-time educator. He wrote a plan for a school, and the Minister of Arts and Sciences, Philipp Albert Stapfer, approved it.

When the French army attacked the town of Stans in 1798, many children lost their homes and families. The Swiss government opened an orphanage and asked Pestalozzi to run it. He arrived on December 5, 1798.

The buildings for the orphanage were not ready when Pestalozzi arrived. On January 14, 1799, many orphans came. Pestalozzi wrote that they were "in a dreadful condition." He took on many roles: teacher, caregiver, and even nurse. He had no school supplies and only one helper, a housekeeper.

Pestalozzi's goal at Stans was like his goal at Neuhof: to combine education with practical work. But this time, he didn't expect the children's work to make money. He saw work as a way to teach skills, efficiency, and helpfulness. He wanted to train their minds to pay attention, observe, and remember. At Stans, Pestalozzi realized how important it was to have a clear, simple method for teaching everyone.

In June 1799, the French army returned to Stans and needed the buildings for their soldiers. The orphanage had to close. Even in that short time, Pestalozzi's success was clear in how much the children improved. He left Stans to recover, hoping to return, but he was not allowed back.

Burgdorf: New Success (1800–1804)

While recovering, Pestalozzi was sent to Burgdorf by Stapfer. He got a small salary and a teaching job at the town's lowest school. The shoemaker who ran the school before Pestalozzi didn't like his ideas, so Pestalozzi soon moved to a different school for children aged five to eight. He continued his teaching experiments there.

A friend suggested a book to Pestalozzi. Even though he didn't know much French, what he understood "threw a flood of light upon my whole endeavor." It confirmed his belief that learning should follow a simple, step-by-step order.

In January 1800, a young teacher named Hermann Krüsi offered to help Pestalozzi. Krüsi learned from Pestalozzi's example. After eight months, school officials praised Pestalozzi. He had taught five and six-year-olds to read, write, draw, and do arithmetic perfectly. The school board promoted him to a higher teaching position.

Because of his success, Pestalozzi opened another school in Burgdorf in October 1800. It was called the "Educational Institute for the Children of the Middle Classes" and was located in the Burgdorf Castle. Two more educators, Johann Georg Tobler and Johann Christoff Büss, joined him. Here, Pestalozzi organized and wrote down many of his teaching methods and ideas.

How Gertrude Teaches her Children (1801)

Pestalozzi became widely known again after publishing How Gertrude Teaches her Children. This book greatly influenced how people thought about education. It was written as 14 letters from Pestalozzi to his friend Heinrich Gessner. In these letters, Pestalozzi explained how he and his team taught at Burgdorf. He shared his thoughts on teaching methods and educational theory. He also wrote about physical education and moral and religious education. Pestalozzi wanted to show that anyone could teach children effectively by breaking down knowledge into simple steps and using well-ordered exercises.

Because of this book's success, people from all over Switzerland and Germany came to see the school in Burgdorf. The school grew, but Pestalozzi still wanted to do more for the poor. He asked the Swiss government for more chances to educate poor children. The government sent two officials to check his work. They gave a good report, and the government decided to make Pestalozzi's school a national institution. Teachers would get salaries, and money would be used to publish textbooks written by Pestalozzi and his staff. With this money, Pestalozzi published three basic books in 1803: The ABC of Sense Perception, Lessons on the Observation of Number Relations, and The Mother's Book.

Two new staff members joined Pestalozzi: Johann Joseph Schmid and Johannes Niederer. Schmid had been a poor student at the institute but became a teacher because of his skills. Niederer was a former minister.

Pestalozzi's family finally moved to the institute to live and work. His son, Jean-Jacques, died in 1801 at age 31. But his daughter-in-law and grandson, Gottlieb, moved from Neuhof to Burgdorf to live at the institute.

Trip to Paris (1804)

Political changes by Napoleon threatened Pestalozzi's school. A group from Switzerland, including Pestalozzi, went to Paris to meet Napoleon. Before leaving, Pestalozzi published his ideas about political efforts. This writing shows how his political, social, and educational ideas were connected. Pestalozzi didn't enjoy his time in Paris because Napoleon wasn't interested in his work.

When he returned, the new Swiss government questioned his right to use the Burgdorf facilities. They said they needed the buildings for their own officials. To avoid public criticism, they offered Pestalozzi an old monastery in Münchenbuchsee. Pestalozzi received other offers, but he accepted the government's offer. In June 1804, his work in Burgdorf ended.

Münchenbuchsee (1804–1805)

Pestalozzi's time in Münchenbuchsee was short. His colleagues suggested he work with Philipp Emanuel von Fellenberg, who ran another school nearby. However, Pestalozzi and Fellenberg didn't get along. After months of planning, they decided to move the school to Yverdon.

Yverdon: A Long-Lasting Effort (1805–1825)

The school in Yverdon was Pestalozzi's longest-running project. He spent the first few months writing, thanks to a gift from the King of Denmark. During this time, he wrote Views and Experiences relating to the idea of Elementary Education.

In July 1805, the Yverdon institute opened. It attracted students and visitors from all over Europe. Many governments sent their own educators to learn from Pestalozzi, hoping to use his system in their own countries. In May 1807, the institute started a newspaper called Die Wochenschrift fur Menschenbildung. It shared ideas about education and reported on the school's progress. At Yverdon, students of all ages were taught, not just young children. They learned German, French, Latin, Greek, geography, history, math, drawing, writing, and singing. At the height of its fame, Pestalozzi was highly respected for his work.

Over time, Pestalozzi felt his colleagues were drifting apart. This caused disagreements, especially between Niederer and Schmid. Niederer gained influence and added subjects that teachers weren't good at teaching. Schmid openly criticized this. The disagreements grew among the staff. In 1810, a government commission visited Yverdon to check the school. Their report liked Pestalozzi's ideas but not how the school was run. This ended any hope of Yverdon becoming a state institution.

Pestalozzi felt unfairly treated. Schmid resigned. Without Schmid, Pestalozzi and Niederer couldn't teach math, so they opened a printing and bookselling business. This failed financially. Friends helped the institute stay open until 1815, when Schmid returned. While Schmid was away, Pestalozzi wrote Swansong, explaining his educational ideas again, and Life's Destiny, a review of his life's work. These were published together in 1826 as Pestalozzi's Swansong.

After his wife died in 1815, Krüsi left the institute. Niederer followed in 1817. Overwhelmed, Pestalozzi asked Schmid for help. Schmid raised money by publishing Pestalozzi's works. The institute stayed open for another 10 years. In 1825, it had to close due to lack of money.

Death

Pestalozzi returned to his old home at Neuhof. He published Pestalozzi's Swansong, which led to some strong disagreements from others. Pestalozzi became ill on February 15, 1827, and passed away two days later in Brugg on February 17, 1827. His last words were, "I forgive my enemies. May they now find peace to which I am going forever."

The words on Pestalozzi's grave say:

Heinrich Pestalozzi:

born in Zurich January 12, 1746

died in Brugg February 17, 1827

Saviour of the Poor on the Neuhof.

Preacher to the People in Leonard and Gertrude

In Stans, Father of the orphan,

In Burgdorf and Münchenbuchsee,

Founder of the New Primary Education.

In Yverdon, Educator of Humanity.

He was an individual, a Christian and a citizen.

He did everything for others, nothing for himself!

Bless his name!

Pestalozzi's Big Ideas

Pestalozzi believed that education should be broken down into simple parts to be fully understood. From his experiences running schools, he felt that every part of a child's life helped shape their personality, character, and ability to think. His teaching methods focused on the child, recognizing that each child is different. He emphasized learning through the senses and allowing students to be active in their own learning.

He worked to simplify the teaching of languages like Latin, Hebrew, and Greek. He also influenced physical education, creating exercises and outdoor activities. These activities were linked to overall learning, moral development, and thinking skills. This showed Pestalozzi's idea of a balanced and independent person.

Pestalozzi's main idea about education was based on four areas of life. He believed that human nature was good. The first three areas were: home and family, work and personal goals, and society and nation. These areas showed how family, individual effort, and the parent-child relationship in society helped a child's character, attitude toward learning, and sense of duty. The last area was "inner sense," which meant that education, by helping people meet their basic needs, leads to inner peace and a strong belief in God.

Pestalozzi's Lasting Impact

Pestalozzi himself said that his most important work wasn't just in the schools he ran. It was in the teaching ideas he used: observing children, training the whole person (mind, body, and heart), and being kind and understanding with students. These ideas were best shown during his six months at Stans. He had a huge impact on all areas of education, and his influence is still felt today.

Friedrich Fröbel, who created the idea of the kindergarten, was one of Pestalozzi's students. Pestalozzi's ideas also inspired Charles Mayo and his sister Elizabeth Mayo. They helped start formal training for teachers of young children in Britain.

Many schools around the world are named after Pestalozzi. These include schools in Germany, North Macedonia, Argentina, Peru, and Puerto Rico. For example, after a big earthquake in Skopje in 1963, Switzerland helped build a new school there. They named it after Pestalozzi and designed it with modern earthquake protection.

The Pestalozzi-Stiftung Hamburg, started in 1847, runs daycare centers and homes for children.

Pestalozzi's teaching methods were used at the school in Aarau that Albert Einstein attended. Einstein said this education helped him picture problems and use "thought experiments." He felt that learning based on freedom and personal responsibility was much better than learning based on strict rules.

The British charity Pestalozzi International Village Trust helps students from developing countries study in the UK and supports other programs overseas.

Today, the Pestalozzi-Fröbel-Haus in Berlin continues to train teachers for nursery schools.

The Pestalozzianum in Zürich was named after Pestalozzi in 1875. This foundation helped train teachers. In 2003, it changed its name to Stiftung Pestalozzianum as its teacher training goals were moved to new university-like colleges.

Kinderdorf Pestalozzi in Trogen, Switzerland, was started in 1945 to create a "children's village" for children affected by war. In 1946, children from war-torn countries moved into the first houses. Later, children from Tibet, Korea, Tunisia, Ethiopia, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Lebanon lived there. Since 1983, Swiss orphans have also lived there. Children can stay for a few weeks or several years. By 2012, the foundation had helped 321,000 children and teenagers in Switzerland and other countries.

The 1989 film Pestalozzi's Mountain tells the story of his life and career. Gian Maria Volonté played Pestalozzi in the movie.

See also

In Spanish: Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi para niños

In Spanish: Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi para niños

- Education in Switzerland

- Jan Amos Komenský

- Johann Julius Hecker

- Johann Ignaz von Felbiger

- Maria Montessori

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |