Harriet Martineau facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Harriet Martineau

|

|

|---|---|

Martineau by Richard Evans

(1834) |

|

| Born | 12 June 1802 |

| Died | 27 June 1876 (aged 74) Ambleside, Westmorland, England

|

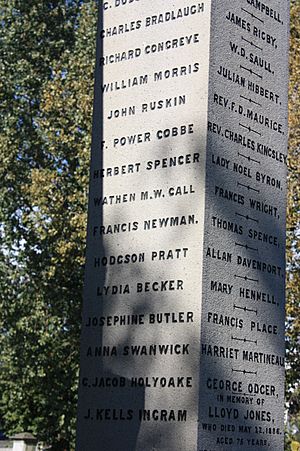

| Burial place | Key Hill Cemetery in Birmingham, UK |

| Known for | Thorough exploration in political, religious and social institutions, as well as the work and roles of women |

| Political party | Whig |

| Spouse(s) | Engaged to John Hugh Worthington, who died before they were able to get married. |

| Relatives | Peter Finch Martineau (uncle) Thomas Michael Greenhow (brother-in-law) |

| Family | Martineau |

| Writing career | |

| Notable works | Illustrations of Political Economy (1834) Society in America (1837) Deerbrook (1839) The Hour and the Man (1841) |

Harriet Martineau (born June 12, 1802 – died June 27, 1876) was an English writer and thinker. Many people see her as the first female sociologist. A sociologist studies how societies work, including how people live together and the rules they follow. Harriet Martineau wrote a lot about how people of different races got along.

She looked at society from many angles, including how religion and women's roles fit in. She also translated important works by a French thinker named Auguste Comte. It was rare for a woman writer in her time to earn enough money to support herself, but Harriet did! Even the young Queen Victoria enjoyed her books. Harriet believed that to understand society, you had to look at everything: politics, religion, and social groups. She also carefully studied how women were treated compared to men. She was very dedicated to ending slavery, a movement called abolitionism.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Harriet Martineau was the sixth of eight children. She was born in Norwich, England. Her father, Thomas, owned a textile factory. Her family were Unitarians, a type of Christian faith. Her mother, Elizabeth Rankin, was the daughter of a sugar refiner.

Harriet's family was well-off financially until about 1825-1826. That's when the stock market and banks had problems. Harriet's relationship with her mother was often difficult. Harriet felt her mother didn't show her enough affection. This feeling influenced some of Harriet's later writings about raising children.

Harriet's mother wanted all her children to read a lot. But she also believed girls should act properly and politely. She didn't want her daughters to be seen writing in public. Despite this, Harriet and her sister Rachel both became successful in their studies.

Education and Learning

Harriet's mother, Elizabeth, made sure all her children got a good education. Since they were Unitarians, both boys and girls were expected to learn. Harriet first learned at home from her older brothers and sisters. Her mother taught her French, and her father taught her Latin. Her brother Thomas taught her math and writing.

When Harriet was nine, she went to a small school run by Mr. Perry. Harriet later said that Mr. Perry's school helped her love learning. She became very interested in Shakespeare, how economies work (political economy), philosophy, and history. Harriet also had some challenges. She had trouble hearing, her handwriting wasn't great, and she worried about her hair.

Later, Harriet went to an all-girls boarding school in Bristol. There, she started studying on her own. She learned Latin, Greek, and Italian. She also studied the Bible more deeply. Harriet started writing more often after her brother James went to college in 1821. James and Harriet were very close, and he suggested writing to help her cope with their separation.

Becoming a Writer

Harriet began to lose her senses of taste and smell when she was young. By age 12, she was deaf and needed to use an ear trumpet to hear. However, she didn't use it until her late twenties because she wanted to avoid being teased. These were the start of many health problems for her.

After her father passed away, Harriet needed to earn money for herself. She became a very active writer. In 1821, she started writing for a Unitarian magazine called the Monthly Repository. In 1823, she published her first book of religious writings.

In 1823, Harriet became engaged to John Hugh Worthington. But he became ill and died before they could marry. Harriet later wrote that she was secretly relieved not to marry him. She said their relationship had been full of stress. Harriet never married.

In 1829, her family's textile business failed. Harriet, then 27, stepped outside the usual roles for women to earn money. Besides sewing, she sold articles to the Monthly Repository. She even won three essay prizes. Her steady work made her a popular writer. Harriet wrote in her autobiography that her father's business failing was "one of the best things that ever happened to us." She felt she could finally "truly live instead of vegetate."

Harriet's first big book was Illustrations of Political Economy. It was a fictional guide to help people understand the ideas of Adam Smith about how economies work. The book was published in 1832. The publisher thought it wouldn't sell well, so they only printed 1,500 copies. But it became very popular, even selling more than books by Charles Dickens! This book helped spread ideas about free markets across the British Empire. Harriet then agreed to write a series of similar stories every month for two years. Her brother James also helped her with this series.

Her later books in the series explained the ideas of other economic thinkers like James Mill and David Ricardo. She also used ideas from Thomas Malthus about how human populations tend to grow faster than the food supply.

Life in London and America

In the early 1800s, society often had strict rules about what was suitable for men and women. Writing was no different. Men usually wrote about social, economic, and political topics. Women were expected to write about romance or home life. But Harriet Martineau shared her strong opinions on many subjects.

Harriet moved to London in November 1832. There, she met many important thinkers like John Stuart Mill and Charles Lyell. She also met famous writers like Florence Nightingale, Charlotte Brontë, and Charles Dickens later in her career.

From 1832 to 1834, Harriet worked on her economic series. She also wrote stories to influence government policy on helping the poor. Some people criticized her ideas, while others praised her.

In 1834, after finishing her economic series, Harriet Martineau visited the United States. She met many people, from ordinary citizens to former US President James Madison. She also visited schools for girls. Harriet strongly supported the movement to end slavery, which was not popular in the U.S. at the time. Her books Society in America (1837) and How to Observe Morals and Manners (1838) caused controversy. These books are now seen as important works in the early field of sociology.

In Society in America, Harriet criticized the poor state of women's education. Her book Illustrations of Political Economy was so successful that by 1834, it sold 10,000 copies a month. This was a huge number for a book at that time.

In 1839, she wrote an article called "The Martyr Age of the United States." It told English readers about the struggles of those fighting to end slavery in America.

When Charles Darwin returned from his voyage on the Beagle in 1836, he met Harriet Martineau. They shared similar backgrounds and political views. Harriet's popular writings about Thomas Malthus's ideas on population may have encouraged Charles Darwin to read Malthus. This reading helped Darwin develop his famous theory of evolution.

Harriet also wrote novels. Deerbrook (1838) was about a difficult love story. It was considered her most successful novel. She also wrote The Hour and the Man (1841), a novel about Toussaint L'Ouverture, a leader who helped Haiti gain independence from slavery.

Illness and Recovery

In 1839, Harriet was diagnosed with a tumor. She visited her brother-in-law, Thomas Michael Greenhow, a doctor in Newcastle upon Tyne. She stayed with his family for six months. She was very ill and had to stay on a couch. Her mother cared for her for a while.

She then moved to Tynemouth, where she slowly got better. She stayed at a boarding house for almost five years. This house is now called the "Martineau Guest House" in her honor. Her illness made her feel the limits placed on women during that time.

Harriet wrote several books while she was ill. A historical plaque marks the house where she stayed. In 1841, she published four children's novels as The Playfellow. In 1844, she wrote Life in the Sickroom: Essays by an Invalid. This book was about her experiences with illness. She also started writing her autobiography, which she finished much later. Important visitors like Richard Cobden and Thomas Carlyle came to see her.

Life in the Sickroom is considered one of her best works. It talked about how to take control of your own space even when you are sick. Critics at the time thought it was strange for a woman to suggest such a thing. They said that because she was ill, her mind must also be sick.

In 1844, Harriet tried a treatment called mesmerism. This was a popular idea at the time, sometimes called 'animal magnetism'. It involved one person influencing another's mind. After a few months, Harriet felt much better. She wrote about her experience in 16 Letters on Mesmerism. This caused a lot of discussion and some disagreement with her family.

Life in Ambleside

In 1845, Harriet moved to Ambleside in the beautiful Lake District. She designed her own house, called The Knoll, Ambleside, and oversaw its building. She spent most of her later life there. Harriet was a single woman with no children. She said her ideal life was "a house of my own among poor improvable neighbors, with young servants whom I might train." She found a good plot of land and enjoyed planning her new home. She moved into The Knoll in April 1846.

Views on Religion and Society

In 1846, Harriet traveled to Egypt, Palestine, and Syria with friends. When she returned, she published Eastern Life, Present and Past (1848). In this book, she shared a big realization she had while looking at the Nile river and ancient tombs. She felt that as humanity developed, ideas about God became more abstract. She believed the final step was a kind of philosophical atheism, though she didn't say it directly. She compared ancient Egyptian beliefs to Christian ideas, noting their similarities. This book showed her moving away from her Unitarian faith.

Harriet wrote Household Education in 1848. She felt that women's education needed to improve. She believed women were naturally good at motherhood and that domestic skills should be taught alongside academic subjects. She thought freedom and reason were the best ways to educate children.

She also gave lectures to children and adults in Ambleside. She talked about health, English and North American history, and her travels in the East. In 1849, she wrote The History of the Thirty Years' Peace, 1816–1846. This was a popular history book written from a "philosophical Radical" point of view. Harriet wrote about many different topics with a strong voice, which was unusual for women at the time.

Harriet also wrote a popular guide book to the Lake District, A Complete Guide to the English Lakes, published in 1855. It was the main guidebook for the area for 25 years.

In 1851, she published Letters on the Laws of Man's Nature and Development with Henry G. Atkinson. In this book, she openly discussed philosophical atheism. She believed there was a "first cause" but that it was unknowable. This book caused a lasting disagreement between Harriet and her beloved brother James, who was a Unitarian clergyman.

From 1852 to 1866, she wrote regularly for Daily News, sometimes writing six articles a week. She wrote over 1,600 articles for the paper in total. She also wrote for the Westminster Review.

Harriet continued her political work in the 1850s and 1860s. She supported the Married Women's Property Bill, which would give married women more control over their own money. She also supported women's right to vote.

In early 1855, Harriet had heart problems. She started writing her autobiography quickly, expecting to die soon. She finished it in three months but decided to publish it after her death. She lived for another two decades! The book was published in 1877.

When Charles Darwin's book The Origin of Species came out in 1859, Harriet supported his theory. She liked that it wasn't based on religious ideas. She wrote that it was "overthrowing (if true) revealed Religion on the one hand, & Natural (as far as Final Causes & Design are concerned) on the other."

Economics and Sociology

Harriet Martineau's book Illustrations of Political Economy helped combine fiction with economic ideas. At the time, fiction was for emotions, and economics was for facts. Harriet's work helped women enter the field of economics. She showed how home economics connected to the larger economy.

Harriet's thoughts on Society in America are good examples of her sociological methods. She believed that general social rules affect every society. These include the idea of progress, the rise of science, and the importance of population and the environment.

Auguste Comte created the name "sociology." Harriet Martineau translated his long book, Cours de Philosophie Positive, into a shorter, easier-to-read version in 1853. Comte himself recommended her translation to his students! Because she introduced Comte's ideas to English speakers and wrote her own sociological works, many people consider Harriet Martineau the first female sociologist.

She taught that studying society must include all its parts: politics, religion, and social groups. She also insisted on including the lives of women. She was the first sociologist to study topics like marriage, children, religious life, and race relations. She also believed that sociologists should not just observe society, but also work to make it better.

Death and Legacy

Harriet Martineau died from bronchitis at her home, "The Knoll," on June 27, 1876, at age 74. She was buried next to her mother in Key Hill Cemetery in Birmingham.

In 1877, her autobiography was published. It was unusual for a woman to publish such a book, especially one that was not religious. The book explored her childhood and her feelings about her mother. It also showed her strong connection to her brother, James.

Today, many experts believe Harriet Martineau is an important, but often overlooked, founder of sociology. Her ideas are still important for understanding society.

In 2014, it was reported that London's National Portrait Gallery has several portraits of Harriet. Her great-niece, Frances Lupton, worked to create more educational opportunities for women.

One of Harriet's popular novels was Deerbrook. It was known for focusing on domestic realism, which means showing everyday life in a realistic way. This novel showed how much her writing had improved.

Books

- Illustrations of taxation; 5 volumes; Charles Fox, 1834

- Illustrations of Political Economy; 9 volumes; Charles Fox, 1834

- Miscellanies; 2 volumes; Hilliard, Gray and Co., 1836

- Society in America; 3 volumes; Saunders and Otley, 1837; (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN: 978-1-108-00373-5); Internet Archive

- Retrospect of Western Travel; Saunders and Otley, 1838, (Project Gutenberg Volume 1, Volume 2)

- How to Observe Morals and Manners; Charles Knight and Co, 1838; Google Books, Project Gutenberg

- Deerbrook; London, 1839; Project Gutenberg

- The Hour and the Man: An Historical Romance, 1841, Project Gutenberg

- The Playfellow (comprising The Settlers at Home, The Peasant and the Prince, Feats on the Fiord, and The Crofton Boys); Charles Knight, 1841

- Life in the Sickroom, 1844

- The Billow and the Rock, 1846

- Household Education, 1848, Project Gutenberg

- Eastern Life. Present and Past; 3 volumes; Edward Moxon, 1848

- The History of the Thirty Years' Peace, A.D. 1816–1846 (1849)

- Feats on the Fiord. A Tale of Norway; Routledge, Warne, & Routledge, 1865, Project Gutenberg

- Harriet Martineau's Autobiography. With Memorials by Maria Weston Chapman; 2 volumes; Smith, Elder & Co, 1877; Liberty Fund.

- A Complete Guide to the English Lakes; John Garnett 1855 and later editions

- H. G. Atkinson and H. Martineau, Letters on the Laws of Man's Nature and Development; Chapman, 1851 (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN: 978-1-108-00415-2)

- A. Comte, tr. H. Martineau, The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte; 2 volumes; Chapman, 1853 (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN: 978-1-108-00118-2)

Archives

The Cadbury Research Library at the University of Birmingham has many of Harriet Martineau's papers and letters.

See also

In Spanish: Harriet Martineau para niños

In Spanish: Harriet Martineau para niños

- History of feminism

- List of sociologists

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |