Charles Lyell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir

Charles Lyell

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Lyell by George J. Stodart

|

|

| Born | 14 November 1797 Kinnordy House, Angus, Scotland

|

| Died | 22 February 1875 (aged 77) Harley Street, London, England

|

| Alma mater | Exeter College, Oxford |

| Known for | Uniformitarianism |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Horner Lyell |

| Awards | Royal Medal (1834) Copley Medal (1858) Wollaston Medal (1866) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Geology |

| Institutions | King's College London |

| Influences | James Hutton; John Playfair; Jean-Baptiste Lamarck; William Buckland |

| Influenced | Charles Darwin Alfred Russel Wallace Thomas Henry Huxley Roderick Impey Murchison Joseph Dalton Hooker |

Sir Charles Lyell (born November 14, 1797 – died February 22, 1875) was a Scottish geologist. He showed how natural processes, still happening today, shaped Earth's history. He is famous for his book Principles of Geology (1830–33). This book taught many people that Earth was formed by the same slow processes we see now.

A philosopher named William Whewell called this idea "uniformitarianism". It means that changes happen gradually over a very long time. This was different from "catastrophism", which said Earth changed due to sudden, big events. Lyell's book convinced many people that Earth's history, or "deep time", was incredibly long.

Lyell also explained climate change. He suggested that shifting oceans and continents caused long-term changes in temperature and rain. He also explained earthquakes and how volcanoes grow slowly. In studying rock layers (called stratigraphy), he divided the Tertiary period into Pliocene, Miocene, and Eocene sections. His idea of a separate period for human history, called the 'Recent', helped start the modern idea of the Anthropocene.

Lyell was a close friend of Charles Darwin. His ideas greatly influenced Darwin's thinking about evolution. Lyell even helped arrange the publication of papers by Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace on natural selection in 1858.

Contents

Biography

Charles Lyell was born on November 14, 1797, in Kinnordy House, Scotland. He was the oldest of ten children in a wealthy family. His father, also named Charles Lyell, was a botanist. He first introduced young Charles to studying nature.

The family's home was near the Grampian Mountains. They also had a home in southern England. This meant Lyell grew up seeing different types of geology.

He went to Exeter College, Oxford, in 1816. There, he studied geology. After graduating in 1819, he started studying law. He traveled through England, observing geological features. In 1823, he became a secretary for the Geological Society of London. As his eyesight worsened, he decided to become a full-time geologist. His first paper was presented in 1826. By 1827, he left law to focus on geology. This led to his fame and the acceptance of uniformitarianism.

In 1832, Lyell married Mary Horner. She was the daughter of Leonard Horner, who was also involved with the Geological Society. They spent their honeymoon on a geological tour in Switzerland and Italy.

During the 1840s, Lyell traveled to the United States and Canada. He wrote two popular books about his travels and geology. These were Travels in North America (1845) and A Second Visit to the United States (1849).

Lyell's wife died in 1873. Two years later, in 1875, Charles Lyell passed away. He was buried in Westminster Abbey. Many places are named after him, including Mount Lyell (California) and a crater on the Moon.

Career and Major Writings

Lyell came from a rich family and also earned money as an author. He worked briefly as a lawyer. In the 1830s, he was a Professor of Geology at King's College London. From 1830 onwards, his books made him famous and provided income.

Each of his three main books was always being updated. They went through many editions during his lifetime. Lyell added new information and changed old ideas based on new evidence.

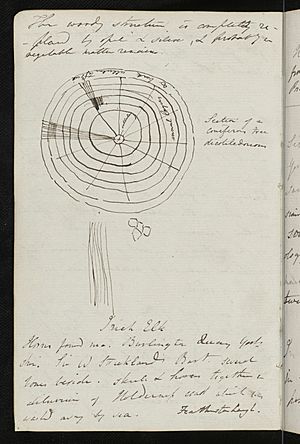

Lyell kept almost 300 notebooks and diaries throughout his life. These show his personal thoughts, observations, and relationships. They include his travels, drafts of letters to people like Charles Darwin, and his geological sketches.

Principles of Geology

Principles of Geology was Lyell's first and most famous book. It was published in three parts from 1830 to 1833. This book made him an important geology expert. It also introduced the idea of uniformitarianism. The book combined his own observations from his travels with existing ideas.

The main idea in Principles was that "the present is the key to the past." This means that we can understand past geological changes by looking at processes happening now. Lyell believed that geological changes happened slowly over very long periods. This idea greatly influenced the young Charles Darwin.

Darwin read Lyell's Principles during his voyage on HMS Beagle. When he saw rock formations on the Cape Verde islands, he realized how important Lyell's ideas were. This helped him understand the geological history of the island.

Darwin and Lyell became close friends. Darwin discussed his ideas about evolution with Lyell from 1842. Lyell encouraged Darwin to publish his work. After Darwin's On the Origin of Species came out in 1859, Lyell finally supported evolution in the tenth edition of Principles.

Elements of Geology

Elements of Geology started as a part of Principles. Lyell wanted it to be a field guide for geology students. But the book grew too large. So, he made it a separate book in 1838. It went through six editions. Later, he made a shorter version called Student's Elements of Geology.

Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man

Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man was published in 1863. It discussed Lyell's ideas on glaciers, evolution, and the age of the human race. The book was seen as a bit disappointing because Lyell was unsure about evolution. He was a religious man and found it hard to fit his beliefs with natural selection.

Scientific Contributions

Lyell studied many geological topics. These included volcanoes, rock layers (stratigraphy), fossils, and glaciology (the study of glaciers). He is most known for developing the idea of uniformitarianism.

Uniformitarianism

From 1830 to 1833, Lyell's book Principles of Geology was published. Its subtitle was "An attempt to explain the former changes of the earth's surface by reference to causes now in operation." This explains his big impact on science. He used his own field studies to explain how Earth changed.

Lyell argued that Earth was shaped by slow forces still at work today. These forces acted over a very long time. This was different from catastrophism, which said that sudden, violent events caused big changes. Lyell believed that geology should be free from ideas that relied on sudden, unexplained events.

The terms uniformitarianism and catastrophism were created by William Whewell. Lyell's Principles of Geology was very important in the mid-1800s. It helped make geology a modern science.

Volcanoes and Geological Dynamics

Before Lyell, people mostly understood earthquakes by the damage they caused. Lyell helped explain the causes of earthquakes. He focused on recent earthquakes and how they caused changes on the surface, like faults and cracks.

Lyell also studied Vesuvius and Etna volcanoes. He concluded that volcanoes grow slowly over time. This was called "backed up-building." Other geologists thought volcanoes formed from sudden upheavals.

Stratigraphy and Human History

Lyell was important in classifying more recent geological deposits. These were known as the Tertiary period. In 1828-1829, he traveled to France and Italy. He found that recent rock layers could be grouped by the number of marine shells in them.

Based on this, he divided the Tertiary period into four parts in 1833. He named them the Eocene, Miocene, Pliocene, and Recent. In 1839, he named the Pleistocene epoch. The Recent epoch, later called the Holocene, included all deposits from human history. Lyell's ideas about these divisions are still discussed today, especially with the idea of the Anthropocene.

Glaciers

In Principles of Geology (1833), Lyell suggested that icebergs could carry large rocks (called erratics). He thought that during warm periods, ice would break off and float over submerged land. As the ice melted, it would drop sediments.

He also believed that fine, angular particles covering much of the world (now called loess) settled from mountain floodwater. Today, some of Lyell's ideas about how geological processes work have been proven wrong. However, many of his observations and ways of analyzing geology are still used today.

Evolution

Lyell first believed that the fossil record showed species going extinct. Around 1826, he read Lamarck's ideas about evolution. He admired Lamarck's courage but was cautious. He wrote that if Lamarck's ideas were true, then humans might have come from apes.

Lyell struggled with how evolution fit with human dignity. He thought that new species appearing naturally would be a "remarkable manifestation of creative Power." He also believed Earth was very old, like Lamarck suggested.

In the first edition of Principles, Lyell said there was no real progression of fossils. The only exception was humans, who had unique intellectual and moral qualities. He rejected Lamarck's idea that animals changed based on habits. He believed species were created with stable features. He thought species would go extinct in a "struggle for existence." He was vague about how new species formed, saying it happened rarely.

Sir John Herschel praised Lyell's book. He said it opened the way for thinking about how extinct species were replaced. He thought new species might arise through natural processes, not miracles. Lyell agreed but kept it quiet to avoid upsetting people.

When Charles Darwin returned from his voyage in 1836, he started to doubt Lyell's ideas about species staying the same. But they remained close friends. Lyell was one of the first scientists to support Darwin's On the Origin of Species. However, Lyell struggled to combine his religious beliefs with evolution. He especially found it hard to believe that natural selection was the main driving force.

Lyell and Hooker helped arrange the joint publication of Darwin's and Alfred Russel Wallace's ideas on natural selection in 1858. Both scientists had come up with the theory independently. Lyell's ideas about slow, gradual change over long periods were very important to Darwin. Darwin believed that populations of organisms changed very slowly.

Even though Lyell rejected evolution when he wrote Principles, he later accepted it. After Darwin's Origin came out, Lyell wrote in his notebook in 1860: "Mr. Darwin has written a work which will constitute an era in geology & natural history." He noted that descendants could become different species over ages.

Lyell's acceptance of natural selection was not complete. It came in the tenth edition of Principles. His book The Antiquity of Man (1863) was seen as a bit disappointing by Darwin. Darwin thought Lyell was too cautious. However, Antiquity sold well. It helped bring the study of mankind into science, away from just theology.

Legacy

Many places are named after Charles Lyell:

- Lyell, New Zealand

- Lyell Butte, in the Grand Canyon

- Lyell Canyon in Yosemite National Park

- Lyell Fork, a part of the Tuolumne River

- Lyell Land (Greenland)

- Lyell Glacier

- Lyell Glacier, South Georgia

- Mount Lyell (California)

- Mount Lyell (Canada)

- Mount Lyell (Tasmania)

- Lyell Avenue (Rochester, NY)

Images for kids

-

Charles Lyell at the British Science Association meeting in Glasgow 1840. Painting by Alexander Craig.

-

"Professor Ichthyosaurus" shows his pupils the skull of extinct man, caricature of Lyell by Henry De la Beche (1830)

-

Lyell argued that volcanoes like Mount Vesuvius had built up gradually.

See also

In Spanish: Charles Lyell para niños

In Spanish: Charles Lyell para niños