James Hutton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James Hutton

FRSE

|

|

|---|---|

Painted by Sir Henry Raeburn (1776)

|

|

| Born | 14 June 1726 |

| Died | 26 March 1797 (aged 70) Edinburgh, Scotland

|

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh University of Paris |

| Known for | Plutonic geology uniformitarianism |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Geology |

| Influences | John Walker |

| Influenced | Charles Lyell |

| Notes | |

|

Member of the Royal Society of Agriculture of France

|

|

James Hutton (1726–1797) was a Scottish scientist who made huge contributions to our understanding of the Earth. He was a geologist, farmer, chemist, and doctor. He is often called the "Father of Modern Geology" because he helped make geology a real science.

Hutton had a big idea: we can understand the Earth's very old history by looking at rocks today. He studied places like Salisbury Crags and Siccar Point in Scotland. He realized that Earth's features are always changing, not staying the same. These changes happen over incredibly long periods.

He was one of the first to support uniformitarianism. This idea says that the natural processes we see happening today (like erosion or volcanoes) are the same ones that shaped the Earth's crust over millions of years. Hutton also believed the Earth was designed to stay suitable for humans forever.

Other scientists like Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon had similar thoughts. But Hutton's work was key in starting the field of modern geology.

Contents

Early Life and Education

James Hutton was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on June 3, 1726. His father was a merchant and died when James was only three years old.

He went to the High School of Edinburgh. He loved mathematics and chemistry. At 14, he started at the University of Edinburgh. He later became a physician's assistant and studied medicine. He even earned a medical degree from the University of Leiden in 1749.

After his studies, Hutton returned to Edinburgh. He worked with a friend, James Davie, to make a chemical called sal ammoniac from soot. This was a profitable business, and the chemical was used for dyeing and metalworking.

Farming and Discovering Geology

Hutton inherited two farms in Berwickshire from his father. In the 1750s, he moved to one of them, Slighhouses. He worked hard to improve the farm, trying new ways to grow plants and raise animals. He even wrote a book about farming, though it was never published.

This farming work sparked his interest in meteorology (the study of weather) and geology (the study of Earth). He wrote in a letter that he loved "studying the surface of the earth." He looked closely at every ditch, pit, or riverbed he found. He noticed that many rocks were made from older materials that had broken down. His ideas about geology started to form around 1760.

Life in Edinburgh and Canal Building

In 1768, Hutton moved back to Edinburgh. He rented out his farms but still kept an eye on them. He built a house overlooking Salisbury Crags, a famous rock formation.

Hutton was an important part of the Scottish Enlightenment. This was a time when many smart people in Scotland shared new ideas. He became friends with famous thinkers like mathematician John Playfair and economist Adam Smith. Hutton didn't teach at the University of Edinburgh. Instead, he shared his scientific discoveries through the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

He also helped build the Forth and Clyde Canal between 1767 and 1774. He used his geological knowledge to help with the project. In 1783, he helped start the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

Later Life and Legacy

From 1791, Hutton suffered from a painful illness. He stopped his fieldwork and focused on writing his books. He died in Edinburgh in 1797 and was buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard.

Hutton never married. He had one son, James Smeaton Hutton, whom he supported financially.

Hutton's Theory of Rock Formations

Hutton developed many ideas to explain the rock formations he saw. He wasn't in a hurry to publish his theories. He loved discovering the truth more than getting famous for it. After about 25 years of work, he presented his main ideas. His book, Theory of the Earth, was read at meetings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1785.

Searching for Evidence

In 1785, Hutton went on a geological trip to Glen Tilt in the Cairngorms. There, he found granite rocks pushing through older schist rocks. This showed him that the granite had been molten (melted) at one point. This proved that granite formed from cooling melted rock, not from water, as others believed. This meant the granite was younger than the schists.

He found similar evidence in Edinburgh, at Salisbury Crags. This spot is now called Hutton's Section. He also found examples in Galloway and on the Isle of Arran.

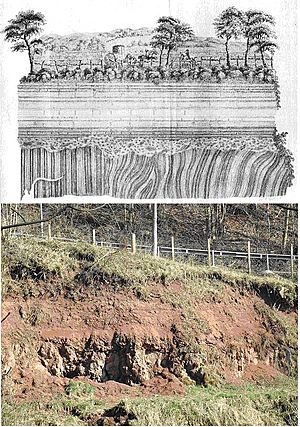

Hutton also looked for angular unconformities. These are places where layers of rock are tilted differently, showing a break in time. In 1787, he found a famous one at Inchbonny, Jedburgh. Here, steeply tilted layers of greywacke were covered by flat layers of Old Red Sandstone. He was very excited to find this!

In 1788, he visited Siccar Point with his friends John Playfair and Sir James Hall. There, they saw a clear example of an unconformity where sloping red sandstone lay on top of vertical greywacke. Playfair later said that looking at it made their minds "grow giddy by looking so far into the abyss of time."

Hutton realized that Earth's history involved countless cycles. Rocks were formed on the seabed, then lifted up, tilted, and eroded. Then, new layers were deposited on top. He believed these processes were very slow, just like what we see today. This meant the Earth had to be incredibly old.

Key Publications

Hutton's full theory appeared in print in 1788. It was called Theory of the Earth; or an Investigation of the Laws observable in the Composition, Dissolution, and Restoration of Land upon the Globe. He wrote that "from what has actually been, we have data for concluding with regard to that which is to happen thereafter." This means we can understand the future by looking at the past.

His most famous line from this work is: "The result, therefore, of our present enquiry is, that we find no vestige of a beginning,–no prospect of an end." This means he saw no sign of when the Earth began or when it would end, based on geological processes.

Because some people found his writing hard to understand, and others thought his ideas were against religious beliefs, Hutton published a longer version of his theory in 1795. This two-volume work included more details and answered criticisms.

Competing Theories of Earth's Formation

Hutton's ideas were very different from the popular "Neptunist" theory of the time. Neptunists, led by Abraham Gottlob Werner, believed all rocks formed from a single giant flood.

Hutton, however, proposed that the Earth's interior was hot. He thought this heat was the engine that created new rocks. Land was worn away by air and water, and these materials settled in the sea. Then, heat from inside the Earth turned these sediments into new rock and pushed them up to form new land. This theory was called "Plutonist" because it involved heat from deep within the Earth (like Pluto, the Roman god of the underworld).

Hutton also believed in deep time for scientific study. Instead of thinking the Earth was only a few thousand years old, he argued it must be much, much older. The slow changes he observed needed vast amounts of time to happen. While modern geology has a different view of Earth's formation and changes, Hutton's evidence for long-term geological processes was very important.

Other Contributions

Understanding Weather

Hutton didn't just study rocks. He also looked at how the atmosphere changes. In the same book as his Earth theory, he published a "Theory of Rain." He suggested that warm air can hold more moisture. So, when two masses of air with different temperatures mix, some moisture turns into visible rain. He studied rainfall and climate around the world to support his ideas.

Earth as a Living System

Hutton believed that biological and geological processes are connected. James Lovelock, who created the Gaia hypothesis in the 1970s, said Hutton saw the Earth as a kind of "superorganism." Lovelock thought Hutton's idea was ignored because scientists in the 1800s focused too much on breaking things down into tiny parts.

Ideas on Evolution

Hutton even had thoughts on evolution. He suggested a process similar to natural selection. He wrote that if an animal or plant isn't well-suited to its environment, it's more likely to die. But those that are best suited will survive and pass on their traits.

He gave the example of dogs. If speed and good eyesight were important for survival, the fastest and sharpest-sighted dogs would survive and have more puppies. If a good sense of smell became more important, then dogs with the best sense of smell would thrive. He saw this "principle of variation" affecting all plants and animals.

Hutton's ideas came from his own experiments in plant and animal breeding. He noticed that some changes could be passed on (heritable) and others were just due to the environment. While he didn't think this process created entirely new species, his thoughts were very advanced for his time. Some historians think Charles Darwin might have been influenced by Hutton's ideas, even if he didn't remember them directly.

Recognition

- A street at the University of Edinburgh's Kings Buildings campus is named after James Hutton.

- The punk rock band Bad Religion quoted Hutton's famous line, "no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end," in their song "No Control."

- Mount Hutton in the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range is named in his honor.

Images for kids

-

Intrusive dike eroded by the River Tay near Stobhall described by Hutton.

-

Geological dike eroded by the River Garry at Dalnacardoch described by Hutton and drawn by Clerk.

-

An eroded outcrop at Siccar Point showing sloping red sandstone above vertical greywacke.

See also

In Spanish: James Hutton para niños

In Spanish: James Hutton para niños

- Deep history

- James Hutton Institute

- Climate of Scotland

- Geology of Scotland

- Shen Kuo

- Time's Arrow, Time's Cycle, a book by Stephen Jay Gould that reassesses Hutton's work

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |