James Lovelock facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James Lovelock

|

|

|---|---|

Lovelock in 2005

|

|

| Born |

James Ephraim Lovelock

26 July 1919 Letchworth, Hertfordshire, England

|

| Died | 26 July 2022 (aged 103) Abbotsbury, Dorset, England

|

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Helen Hyslop

(m. 1942; died 1989)Sandy Orchard

(m. 1991) |

| Children | 4 |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | The properties and use of aliphatic and hydroxy carboxylic acids in aerial disinfection (1947) |

James Ephraim Lovelock (born 26 July 1919 – died 26 July 2022) was an English scientist, environmentalist, and thinker about the future. He is most famous for suggesting the Gaia hypothesis. This idea says that Earth works like a giant, self-regulating system, almost like a living organism.

Lovelock earned a PhD in medicine. Early in his career, he did experiments on freezing and thawing small animals like rodents. His work even helped shape ideas about cryonics, which is the freezing of humans. He also invented a special tool called the electron capture detector. Using this tool, he was the first to find chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) spread widely in the atmosphere. Later, while helping NASA design science tools, he came up with his famous Gaia hypothesis.

In the 2000s, Lovelock suggested a way to help fight climate change by encouraging algae to grow more, which would absorb carbon dioxide. He was a strong supporter of nuclear energy. He believed that using nuclear power was the best way to stop global warming and reduce harmful greenhouse gases. He wrote several books about the environment based on his Gaia hypothesis.

Contents

Early life and education

James Lovelock was born in Letchworth Garden City, England. His mother, Nellie, was a socialist and supported women's right to vote. She didn't let him get the smallpox vaccine as a child. His father, Tom, learned to read later in life and ran a bookshop. James grew up in a Quaker family, which taught him to think for himself.

The family moved to London. James didn't enjoy school much at Strand School because he disliked authority. He couldn't afford university right away, which he later felt was a good thing. It stopped him from focusing too much on one area and helped him develop his broad ideas like the Gaia theory.

Career and discoveries

After school, Lovelock worked at a photography company and studied chemistry at the University of Manchester in the evenings. He later got a job with the Medical Research Council, working on ways to protect soldiers from burns. He refused to use animals for experiments and instead tested heat radiation on his own skin, which he described as very painful. During World War II, he was a conscientious objector (someone who refuses to fight in a war for moral reasons). However, after learning about Nazi crimes, he tried to join the military, but his medical research was considered too important.

In 1948, Lovelock earned his PhD in medicine. For the next 20 years, he worked at the National Institute for Medical Research in London. He also did research in the United States at places like Yale University and Harvard University.

Freezing experiments

In the mid-1950s, Lovelock experimented with freezing small animals. He found that hamsters could be frozen and then successfully brought back to life. Even when 60% of the water in their brains turned to ice, the hamsters showed no bad effects. This research was important for the ideas behind cryonics, which is the practice of freezing humans.

Lovelock even joked that he might have accidentally invented the tabletop microwave oven during these experiments! He found he could bake a potato using his equipment, which was designed to heat frozen hamsters more gently.

Working with NASA

Lovelock was a lifelong inventor. He created many scientific tools, including some for NASA's missions to explore other planets. It was while he was a consultant for NASA that he came up with the Gaia hypothesis, which is what he is most famous for.

In 1961, NASA asked Lovelock to create sensitive tools to study the atmospheres and surfaces of other planets. NASA's Viking program later visited Mars to see if life existed there. Lovelock became interested in the air on Mars. He thought that if there was life on Mars, it would change the planet's atmosphere. However, he found that the Martian atmosphere was very stable, mostly made of carbon dioxide, with very little oxygen or methane. This made him think that there was no life on Mars. The Viking probes still searched for life, but didn't find any.

Lovelock also invented the electron capture detector. This tool helped scientists discover how long chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) stayed in the atmosphere and their role in damaging the ozone layer high above Earth.

Lovelock became a Fellow of the The Royal Society in 1974, which is a very high honor for scientists. He also led the Marine Biological Association for several years.

He worked as an independent scientist from a laboratory he called his "experimental station" in a barn in South West England.

CFCs and the ozone layer

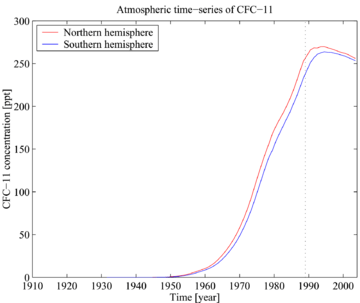

After creating his electron capture detector, Lovelock was the first to find CFCs spread widely in the atmosphere in the late 1960s. He found a small amount of CFC-11 over Ireland. In 1972, he traveled from the northern hemisphere to Antarctica, measuring CFC-11 in 50 air samples. He found the gas everywhere. At first, he didn't realize that CFCs breaking down in the upper atmosphere would release chlorine and harm the ozone layer. He thought they posed "no conceivable hazard" (meaning no toxic danger).

However, his findings were the first important data showing how common CFCs were in the air. Later, other scientists, Sherwood Rowland and Mario Molina, discovered that CFCs could indeed damage the ozone layer. They won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for this discovery, which was partly inspired by Lovelock's work.

The Gaia hypothesis

The Gaia hypothesis was developed by Lovelock in the 1960s. It came from his work for NASA and his thoughts about how Earth works. The hypothesis suggests that all living things and non-living parts of Earth (like the air, oceans, and rocks) are connected. They form a complex system that acts like a single, self-regulating organism.

The idea was named after Gaia, the ancient Greek goddess of Earth, a suggestion from his friend, the novelist William Golding. The hypothesis says that the Earth's living parts (the biosphere) help control the environment to keep conditions suitable for life.

Many environmentalists liked the Gaia hypothesis. However, some scientists, especially evolutionary biologists, were not sure about it. They wondered how natural selection, which works on individual organisms, could lead to the whole planet regulating itself.

To answer these questions, Lovelock and Andrew Watson created a computer model called Daisyworld in 1983. This model imagined a planet with black and white daisies. Black daisies absorb more heat, and white daisies reflect more. As the star's energy changed, the daisies would grow in different amounts. This would help keep the planet's temperature stable, showing how simple life forms could affect the whole planet's climate.

In his 2006 book, The Revenge of Gaia, Lovelock suggested that humans were harming Gaia by damaging rainforests and reducing the number of different species. He warned that this could make global warming much worse and make much of Earth unlivable for humans by the middle of the century. However, in 2012, Lovelock said he had "gone too far" in his predictions and that he had been "alarmist" about how quickly climate change would happen.

In his 2009 book, The Vanishing Face of Gaia, he said that sea levels were rising and Arctic ice was melting faster than models predicted. He thought we might have already passed a "tipping point" where Earth's climate could become permanently hot.

Nuclear power and climate

Lovelock became very worried about global warming caused by the greenhouse effect. In 2004, he surprised many environmentalists by saying that "only nuclear power can now halt global warming." He believed nuclear energy was the only real choice to provide lots of energy for people while also cutting down on greenhouse gases. He was a strong supporter of Environmentalists for Nuclear Energy.

He argued that nuclear radiation and nuclear power are a normal part of the environment. He also pointed out that places with high levels of radiation, like around Chernobyl, often have rich wildlife. He felt that people worried too much about nuclear waste, which he saw as less harmful than the huge amounts of carbon dioxide we release.

In 2019, Lovelock suggested that opposition to nuclear power was due to misleading information, possibly from the coal and oil industries, and that some environmental groups might have been influenced by this.

Views on climate change

In 2006, Lovelock wrote that global warming could lead to a future where only a few people survive in the Arctic. He urged communities to prepare for big changes. He predicted that much of Europe could become desert.

However, in a 2012 interview, Lovelock admitted he had been "alarmist" about the speed of climate change. He said, "All right, I made a mistake." He noted that the world hadn't warmed as much as he once thought since the year 2000. He still believed climate change was happening, but that its worst effects would be further in the future.

He also said that scientists can never be completely certain about anything. He felt that some environmentalists treated global warming like a religion, using guilt to try and convince people.

In 2012, Lovelock also supported fracking for natural gas as a cleaner option than coal. He disliked wind turbines and called the idea of "sustainable development" meaningless.

In his 2019 book, Novacene, Lovelock suggested that very smart machines (superintelligence) might take over and help save the ecosystem. He thought these machines might need to keep organic life around to keep the planet's temperature suitable for electronic life.

Ocean fertilisation idea

In 2007, Lovelock and Chris Rapley suggested building "ocean pumps." These pumps would bring water up from deep in the ocean to help algae grow more on the surface. The idea was to move more carbon dioxide from the air into the ocean.

This idea got a lot of attention and some criticism. Other scientists worried that bringing deep water up might actually release more carbon dioxide. Lovelock later said his idea was meant to spark interest and encourage more research.

Sustainable retreat

Lovelock also developed the idea of "sustainable retreat." He believed that the time for "sustainable development" was over. Instead, he thought humans needed to change where they live and how they get food to adapt to global warming. This meant planning for large groups of people to move from low-lying areas and focusing on keeping civilization going. He emphasized using fewer resources or less harmful types of resources.

Prizes and other honours

Lovelock received many important awards. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1974. This honor recognized his important work in many areas, including studying infections, freezing living cells, and inventing the electron capture detector.

He also won the Tswett Medal for Chromatography (1975), the American Chemical Society Award in Chromatography (1980), and the Dr A.H. Heineken Prize for Environmental Sciences (1990). In 2006, he received the Wollaston Medal, the highest award from the Geological Society of London.

He was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1990 and a Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH) in 2003 for his services to global environmental science.

Personal life

James Lovelock married Helen Hyslop in 1942, and they had four children. Helen passed away in 1989. He later married Sandy Orchard in 1991. He described his life with Sandy as "unusually happy" in a simple, beautiful home.

Lovelock lived to be over 100 years old. He passed away at his home in Abbotsbury, England, on 26 July 2022, which was his 103rd birthday. He died from problems related to a fall.

Portraits

The National Portrait Gallery, London has a portrait of Lovelock by artist Michael Gaskell. The gallery also has two photo portraits of him. A sculpture of Lovelock's head is part of the Environment Triptych by sculptor Jon Edgar.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: James Lovelock para niños

In Spanish: James Lovelock para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |