Sense of smell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids {{{Name}}} |

|---|

The sense of smell, also called olfaction, is how we notice different smells or odors. It's a very important sense! Smell helps us find good food, warn us about dangers, and even plays a big role in how we taste things.

For humans, smelling happens when tiny odor molecules connect with special receptors inside our nasal cavity (our nose). These receptors then send signals through the olfactory system to our brain. Special areas in the brain, like the olfactory bulb, start to process these signals. This helps us identify smells, connect them to memories, and even feel emotions about them.

Sometimes, people can have problems with their sense of smell. This can include losing it completely (called anosmia), or having it change. These issues can be caused by damage to the nose, the smell receptors, or problems in the brain. Common causes include colds, head injuries, or certain brain diseases.

Contents

Exploring the History of Smell

People have been curious about smell for a long time. Early scientific studies, like one by Eleanor Gamble in 1898, looked at how smell compared to other senses.

An ancient Roman philosopher named Lucretius (who lived in the 1st century BCE) thought that different smells came from different shapes and sizes of "atoms." He believed these tiny particles would fit into our smell organs. Today, we know these are odor molecules!

Modern science has shown Lucretius was somewhat right. In 2004, Linda B. Buck and Richard Axel won the Nobel Prize for finding the proteins that act as smell receptors. They showed that each smell receptor recognizes a specific part or type of odor molecule. It's like a "key-lock" system: if an airborne molecule fits into a receptor, that nerve cell will react. Humans have fewer active smell receptor genes than many other mammals.

Scientists are still trying to fully understand how our brains process and understand smells. One idea, the shape theory, suggests that each receptor detects a specific feature of an odor molecule. Another idea, the vibration theory, suggests that receptors might detect the vibrations of odor molecules. We don't have one theory that explains everything about smell yet!

What Does Smell Do?

How Smell Helps Us Taste

When we eat, our brain combines information from our ears, touch, taste, and smell to create the full experience of "flavor." Smell, especially what's called retronasal smell, is super important for flavor. When you chew food, it releases odor molecules. These molecules go up into your nasal cavity as you breathe out. Because of this, the smell of food feels like it's coming from inside your mouth.

Your tongue can only tell the difference between five basic tastes (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, umami). But your nose can tell apart hundreds of different substances, even in tiny amounts! So, while your tongue gives you the basic taste, your nose adds all the rich details that make up a food's flavor. The smell part of flavor happens when you breathe out, while regular smelling happens when you breathe in.

Smell and Hearing

Believe it or not, some studies in rodents show that smell and sound information can meet in the brain. This mixing of smell and sound might create a new kind of perception, sometimes called "smound." Just like flavor comes from smell and taste working together, a smound might come from smell and sound working together.

Avoiding Close Relatives

Animals, including humans, can sometimes detect family members through smell. This is linked to special genes called MHC genes (or HLA in humans). These genes are important for the immune system. Generally, offspring from parents with different MHC genes have stronger immune systems.

Mothers can often identify their biological children by their body odor. This ability to smell relatives helps avoid inbreeding, which can be harmful. For example, mice tend to avoid mating with others who have similar scent signals from their genes.

Guiding Movement with Smell

Some animals use scent trails to find their way around. For example, social insects might leave a scent trail to a food source. A tracking dog can follow the scent of its target for days. Scientists have studied different ways animals follow scents, like moving towards a stronger smell or using wind direction. The way air moves (its turbulence) affects how well they can follow a scent.

Smell and Your Genes

Different people smell different odors, and much of this is because of differences in our genes. Our odorant receptor genes are one of the largest gene families in the human body.

For example, a specific gene called OR5A1 affects whether you can smell β-ionone, which is a key aroma in many foods and drinks. Another gene, OR2J3, is linked to being able to detect the "grassy" smell of cis-3-hexen-1-ol. Even whether you like or dislike cilantro (coriander) has been connected to the olfactory receptor OR6A2.

How Smell Varies in Animals

The importance and strength of smell are different for various animals. Most mammals have a great sense of smell. However, most birds don't, except for a few like petrels, some vultures, and kiwis. Recent studies even suggest that king penguins might use smells to find their colony and recognize other penguins.

Smell is very important for carnivores and ungulates (hoofed animals) who need to be aware of each other. It's also vital for animals that sniff out their food, like moles. Animals with a strong sense of smell are called macrosmatic, while those with a weak sense of smell are called microsmatic.

Dogs, for instance, have a sense of smell that is estimated to be ten thousand to a hundred thousand times better than a human's. This means they can detect tiny amounts of a smell in the air that we would never notice.

- Scenthounds, a group of dogs, can smell one to ten million times better than humans.

- Bloodhounds have the best sense of smell of any dog, being ten to one hundred million times more sensitive than a human's. They were bred to track humans and can follow a scent trail that's several days old.

- The Basset Hound has the second-most sensitive nose among dogs.

Grizzly bears have a sense of smell seven times stronger than a bloodhound's! This helps them find food underground. Bears can smell food from up to eighteen miles away. Because they are so big, they often scare away other predators to get their food.

The sense of smell is less developed in some primates and doesn't exist at all in cetaceans (whales and dolphins), who rely more on their sense of taste. In some animals, smell is very good at detecting pheromones. For example, a male silkworm moth can sense just one molecule of a special pheromone called bombykol.

Even fish have a good sense of smell in water. Salmon use their smell to find their way back to their home streams. Catfish use smell to identify other catfish and keep their social order. Many fish use smell to find mates or to know if food is nearby.

Human Smell Abilities

For a long time, people thought humans could only distinguish about 10,000 unique odors. However, newer research suggests that the average person can tell the difference between over one trillion unique odors! This estimate is actually "conservative," meaning it might be even higher. This shows that the human olfactory system, with its many different receptors, is much better at telling apart different smells than previously thought.

However, being able to tell smells apart is not the same as being able to identify them consistently. People might be able to distinguish between many smells, but they might not be able to name each one.

How Smell Works in Vertebrates

The Main Olfactory System

In humans and other animals with backbones (vertebrates), smells are detected by special cells called olfactory sensory neurons. These are found in the olfactory epithelium, a patch of tissue inside your nose. The size of this tissue gives a clue about an animal's sense of smell. Humans have about 10 square centimeters of this tissue, while some dogs have 170 square centimeters! A dog's olfactory tissue also has many more receptors packed into each square centimeter.

When odor molecules enter your nose, they dissolve in the mucus that lines the upper part of your nasal cavity. Then, they are detected by the receptors on the olfactory sensory neurons. This mucus acts like a solvent for the odor molecules and is replaced often.

Receptor Neurons

When an odor molecule connects to a receptor, it causes a signal to be sent in the neuron. In mammals, this signal involves a chemical process that opens channels in the cell, allowing charged particles (like calcium and sodium) to flow in. This flow creates an electrical signal, called an action potential, which is how nerve cells communicate. This process is similar to how light is detected by cells in your eyes, suggesting they might have evolved from a common ancestor.

Sending Signals to the Brain

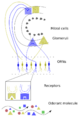

The olfactory sensory neurons send their signals through nerve fibers to the olfactory bulb in the brain. These fibers pass through tiny holes in a bone called the cribriform plate. In the olfactory bulb, the signals from many sensory neurons meet in small structures called glomeruli.

Special cells called mitral cells in the olfactory bulb then receive this information from the glomeruli. These mitral cells send the smell information to other parts of the brain, like the olfactory cortex. Here, many signals are processed to create your overall perception of a smell.

The brain's piriform cortex seems to help figure out the chemical structure of odor molecules. Another part of the piriform cortex helps categorize smells and see how similar they are (like "minty" or "woody"). The orbitofrontal cortex is where you become consciously aware of the smell.

Smell information is also strongly linked to long-term memory and emotional memory. This is probably because the smell system is closely connected to the limbic system and hippocampus, which are brain areas involved in emotions and memory.

Interestingly, each of your two nostrils sends separate smell information to the brain. If each nostril smells a different odor, you might experience a "smell rivalry," similar to how your eyes might see two different images at once.

How Insects Smell

Insects rely heavily on their sense of smell for many important tasks. They use it to find food, avoid predators, locate mates (using pheromones), and find places to lay their eggs. For many insects, smell is their most important sense.

Insects mainly use their antennae and special mouth parts called maxillary palps to detect odors. Inside these organs are tiny neurons called olfactory receptor neurons, which have receptors for scent molecules. Some insects, like Drosophila flies, have thousands of these neurons.

Insects can smell and tell apart thousands of different airborne chemicals, even in very small amounts. They are very sensitive and selective. Some insects, like the Deilephila elpenor moth, use smell to find their food sources.

How Plants Sense Smells

Even plants can "smell"! The tendrils of some plants are very sensitive to airborne chemicals. For example, parasitic plants like dodder use this ability to find their favorite host plants and attach to them.

Plants can also detect when animals are eating their leaves by sensing the chemicals released. When threatened, plants can then take defensive actions, like moving protective chemicals to their leaves.

Machines That Smell

Scientists have created ways to measure how strong odors are, especially to analyze unpleasant smells coming from factories or landfills. Since the 1800s, industrial areas have had problems with bad smells affecting nearby communities.

The basic idea of odor analysis is to see how much "pure" air is needed to dilute a smelly sample until it can no longer be told apart from pure air. Since everyone smells things differently, a "smell panel" of several people is used to sniff the diluted air samples. A special device called a field olfactometer can help determine how strong an odor is.

Many air quality agencies have rules about how strong an odor can be before it crosses into a neighborhood. These rules help control smells from industries, landfills, and sewage treatment plants.

Ways to Classify Smells

Scientists have tried to create systems to classify different odors:

- Crocker-Henderson system: This system rates smells on a scale from 0-8 for four main smells: fragrant, acid, burnt, and caprylic.

- Henning's prism

- Zwaardemaker smell system: Invented by Hendrik Zwaardemaker.

Smell Disorders

Here are some terms for problems related to the sense of smell:

- Anosmia: The complete inability to smell.

- Hyperosmia: An unusually strong sense of smell.

- Hyposmia: A decreased ability to smell.

- Presbyosmia: The natural decline in the sense of smell that happens with old age.

- Dysosmia: A distortion in the sense of smell.

- Parosmia: A distortion in how you perceive an odor (e.g., something familiar smells bad).

- Phantosmia: Smelling something that isn't there, like a "hallucinated smell."

- Heterosmia: Inability to tell different odors apart.

- Olfactory reference syndrome: A psychological condition where a person wrongly believes they have a strong body odor.

- Osmophobia: A strong dislike or extreme sensitivity to odors.

Viruses can also affect the cells in your nose that detect smells, leading to a loss of smell. About 50% of people with COVID-19 experience some kind of smell disorder, including anosmia and parosmia. Other viruses, like SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV, and even the flu, can also disrupt your sense of smell.

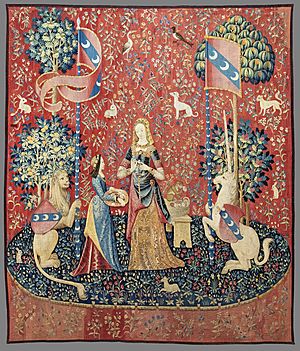

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Olfato para niños

In Spanish: Olfato para niños

- Electronic nose

- Evolution of olfaction

- Nasal administration

- Olfactory ensheathing cell

- Olfactory fatigue

- Scent transfer unit

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |