Hall of Fame for Great Americans facts for kids

|

Hall of Fame Complex

|

|

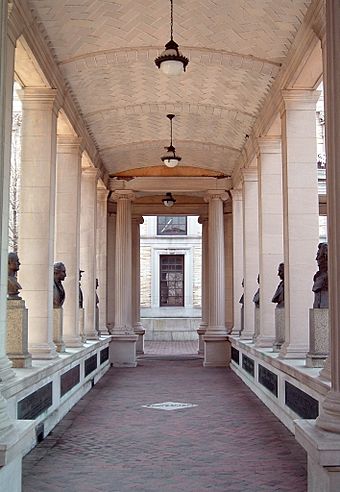

View of the Hall of Fame for Great Americans

|

|

| Location | Bronx Community College campus, The Bronx, New York |

|---|---|

| Area | 2 acres (0.81 ha) |

| Built | 1901 |

| Architect | Stanford White |

| Architectural style | Classical Revival, Beaux-Arts |

| NRHP reference No. | 79001567 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | September 7, 1979 |

The Hall of Fame for Great Americans is an outdoor art gallery. It is located on the campus of Bronx Community College in The Bronx, New York City. It was the very first hall of fame built in the United States.

The Hall of Fame honors 102 important Americans. These people were chosen for their great achievements. The building itself is a beautiful, long, covered walkway with rows of columns. It is 630 feet (190 m) long. Along the walkway, there are 96 bronze statues called busts, which are sculptures of a person's head and shoulders.

A wealthy woman named Helen Gould paid for the building. It opened on May 30, 1901. For many years, it was a symbol of American pride. The last people were chosen for the Hall of Fame in 1976.

Over time, the building and the busts needed repairs. In 2017, the busts of two Confederate generals, Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, were removed. This happened after protests against monuments that honored the Confederacy.

Contents

What the Hall of Fame Looks Like

The Hall of Fame was designed by the famous architect Stanford White. He made it look like the grand buildings of ancient Greece and Rome. The long, open-air walkway is called a loggia. It wraps around the Gould Memorial Library.

The walkway is about 10 feet 3 inches (3.12 m) wide. It has low walls called parapets on the side. The gates at the north and south entrances have special messages carved into them. One says, "Enter with Joy that those within have lived."

Busts and Plaques

The Hall of Fame has 96 bronze busts of the honored people. Each bust sits on a stand. Below each one is a bronze plaque. The plaque tells you the person's name, important dates, and a famous quote from them.

The busts were made by many different sculptors over many years. They are grouped by what the person was famous for. For example, authors are at one end, and inventors are at the other.

History of the Hall of Fame

The idea for the Hall of Fame came from Dr. Henry Mitchell MacCracken. He was the head of New York University (NYU) at the time. He wanted to cover a large retaining wall next to the university's new library. He was inspired by a similar "Hall of Fame" in Munich, Germany.

In 1900, Helen Gould, a philanthropist who donated money to good causes, gave $100,000 to build it. This made the project possible.

Choosing the Honorees

To be chosen, a person had to be an American citizen. They also had to have been deceased for at least 10 years. This rule was later changed to 25 years. This was to make sure only people with lasting importance were selected.

A group of 100 important people from across the country, called electors, voted on who should be included. In the first election in 1900, they chose 29 people. Some of the first honorees were George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Benjamin Franklin.

At first, only people born in the U.S. could be chosen. In 1914, the rules changed to allow citizens born in other countries to be honored as well.

A Popular Place

For many years, the Hall of Fame was very popular. It received up to 50,000 visitors a year. Newspapers reported on the elections, and people were excited to see who would be chosen next.

More busts were added over the years. By 1930, all 65 people who had been elected had a bust on display. Elections were held every five years. Famous people like Susan B. Anthony, Theodore Roosevelt, and Thomas Edison were added.

In 1945, Booker T. Washington became the first Black American to be honored in the Hall of Fame.

Decline and Changes

By the 1960s, the Hall of Fame was becoming less famous. Other halls of fame had opened, many for sports and entertainment, which were more popular.

In 1973, NYU sold its Bronx campus to Bronx Community College (BCC). The Hall of Fame was on this campus. For a while, it was unclear who would take care of it. Funding for the Hall of Fame was cut, and it began to fall into disrepair. The busts started to corrode, and fewer people visited.

The last election was held in 1976. Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross, was one of the last people chosen. However, there was not enough money to create busts for her and three others.

Restoration and Recent Years

In the 1980s and 1990s, efforts began to save the Hall of Fame. The state of New York provided money to fix the roof and restore the busts. The project was finished in 1997 and won an award for its excellent restoration work.

In August 2017, the busts of Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson were removed. This decision was made because of national discussions about Confederate monuments. Their removal left two empty spots in the hall.

Today, the Hall of Fame is cared for by Bronx Community College. It remains an important historical site and a beautiful piece of architecture, even though many of the people it honors are not as well-known as they once were.

How People Were Nominated

Anyone from the public could suggest a name. A board of electors, made up of respected writers, historians, and leaders, would then vote. To be elected, a nominee usually needed to get votes from more than half of the electors.

The electors came from every state in the U.S. To avoid any unfairness, officials from NYU were not allowed to be electors.

After the electors voted, the NYU senate had to approve their choices. This system was used until the final elections in the 1970s.

A Few of the Honorees

The Hall of Fame honors people from many different fields. Here are some of the famous people you can find there:

- Presidents: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, Theodore Roosevelt

- Inventors: Eli Whitney (cotton gin), Samuel Morse (telegraph), Alexander Graham Bell (telephone), Thomas Edison (light bulb)

- Authors: Washington Irving, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Mark Twain

- Scientists: John James Audubon (naturalist and painter), Asa Gray (botanist)

- Reformers: Susan B. Anthony (women's rights leader), Booker T. Washington (educator)

See also

In Spanish: Salón de la Fama para Americanos Ilustres para niños

In Spanish: Salón de la Fama para Americanos Ilustres para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |