Telegraphy facts for kids

Telegraphy is a way to send messages over long distances using special codes. Instead of sending a physical letter, you send signals. Think of it like sending a secret message that only the receiver understands. For example, using flags to spell out words is a type of telegraphy. But sending a message with a pigeon isn't, because the pigeon carries a physical object.

The first widely used telegraph was the Chappe telegraph. It was an optical telegraph invented by Claude Chappe in France in the late 1700s. This system used signals you could see, like moving arms on towers. Later, in the mid-1800s, the electric telegraph became popular. It used wires and electricity. Important inventors like Cooke and Wheatstone in Britain and Samuel Morse in the United States helped create these systems. Morse's system, with its famous Morse code, became a worldwide standard.

Other types of telegraphs also existed. The heliograph used mirrors to flash sunlight messages, often in places without electric wires. Later, in the early 1900s, wireless telegraphy (radio) was invented. This allowed messages to travel without any wires at all, which was very useful for ships at sea and for sending messages across oceans.

For a while, sending a telegram was a popular way to send important messages quickly. Machines like teleprinters helped send these messages faster. But as the telephone became common, people could talk instantly, making telegrams less popular. By the end of the 1900s, the internet and email took over most of the remaining uses for telegraphy.

Contents

- What is Telegraphy?

- How Telegraphy Started

- Early Ways to Send Signals

- Optical Telegraphs: Signals You Could See

- Electric Telegraphs: Wires and Codes

- Machines That Typed Messages (Teleprinters)

- Sending Messages Across Oceans

- Sending Pictures by Telegraph (Facsimile)

- Wireless Telegraphy: Radio Waves!

- Telegrams: Messages Delivered to Your Door

- The Rise of Telex

- Why Telegraphy Became Less Common

- How Telegraphy Changed the World

- See also

What is Telegraphy?

Understanding Telegraphy Terms

The word telegraph comes from two Ancient Greek words. Tele means 'at a distance', and graphein means 'to write'. So, a telegraph literally means 'to write at a distance'. Claude Chappe, who invented the semaphore telegraph, created this word.

A telegraph is a machine that sends and receives messages far away. When people say 'telegraph,' they usually mean an electrical telegraph that uses wires. Wireless telegraphy means sending messages using radio waves, without wires.

Some people, like Samuel Morse, thought a true telegraph had to both send and record messages. They saw things like smoke signals as just 'semaphores' because they only sent messages, not recorded them. Morse believed the first true telegraph was invented in 1832 by Pavel Schilling.

A message sent by an electrical telegraph was called a telegram. If it went through an underwater cable, it was a cablegram, often just called a 'cable'. The word 'gram' also comes from Greek and means 'something written'. So, a telegram is 'something written from a distance'.

Later, a Telex was a message sent using a special network of teleprinters, like an early version of email for businesses. A wirephoto was a picture sent by telegraph for newspapers. Even today, important secret messages between governments are sometimes still called 'diplomatic cables,' no matter how they are sent.

How Telegraphy Started

Early Ways to Send Signals

Sending messages over long distances using signals is a very old idea. One of the earliest examples comes from the Great Wall of China. As far back as 400 BC, people used fires or drums to send warnings. By 200 BC, they had complex flag signals. During the Han dynasty, people used flags and fires, making smoke during the day and bright flames at night. By the Tang dynasty, a message could travel about 1,100 kilometers (700 miles) in just 24 hours! The Ming dynasty even used artillery for signals. These systems were clever, but they could only send a few pre-set messages, like 'enemy approaching'.

In Europe, the Roman army also used signal fires often. One interesting system was invented by Aeneas Tacticus around 400 BC. It used two water-filled pots that drained at the same time. Markers on a floating scale showed which message was being sent. Torches helped keep the pots draining in sync.

Most early signal systems could not send any message you wanted. They were limited to a few pre-arranged signals. However, the ancient Greek historian Polybius described a system using torches and a special grid (the Polybius square) that could spell out any letter. This was a true telegraph idea. Later, in 1616, Franz Kessler invented a lamp inside a barrel with a shutter. This allowed signals to be seen from far away using a telescope.

Optical Telegraphs: Signals You Could See

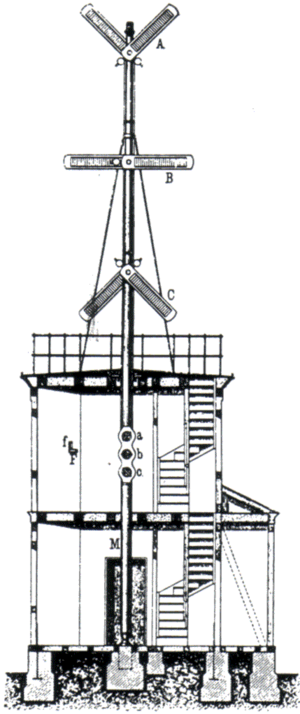

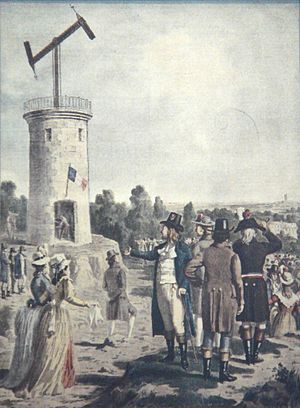

An optical telegraph uses a line of stations, often on towers or high points. These stations signal to each other using moving shutters or paddles. This type of signaling was called semaphore. Robert Hooke suggested an optical telegraph in 1684. Sir Richard Lovell Edgeworth experimented with one in 1767.

The first successful optical telegraph network was invented by Claude Chappe in France in 1793. France needed a fast way to communicate during the French Revolution. In 1791, the Chappe brothers sent a message 16 kilometers (10 miles). By 1792, a line of stations connected Paris and Lille, about 230 kilometers (140 miles) away. This system quickly reported news of battles.

Optical telegraphs depended on good weather and daylight. They could only send about two words per minute. France decided to replace its system with an electric telegraph in 1846. The last commercial optical telegraph stopped working in Sweden in 1880.

Electric Telegraphs: Wires and Codes

Early ideas for electric telegraphs included using static electricity or chemical reactions. Francis Ronalds built an experimental system in 1816. He offered it to the British Navy, but they thought their optical telegraph was enough.

Eventually, people focused on systems using electromagnets. Pavel Schilling created an experimental system in 1832. The first working electric telegraph was built by Carl Friedrich Gauss and Wilhelm Eduard Weber in 1833. It connected two buildings about 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) apart in Germany.

The first commercial electric telegraph was patented by William Fothergill Cooke and Charles Wheatstone in Britain in 1837. It was first used on the London and Birmingham Railway. By 1839, a system was installed on the Great Western Railway over 21 kilometers (13 miles). Cooke eventually opened his telegraph to the public, allowing people to send messages.

Most early electric systems needed many wires. But the system developed in the United States by Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail used just one wire. This system introduced the famous Morse code. By 1844, the Morse system connected Baltimore to Washington. By 1861, it linked the east and west coasts of North America.

The Morse system became the official standard for telegraphy in Europe in 1851. It used a revised code that became the basis for International Morse Code. However, Britain and the United States continued to use their own systems for many years.

Telegraphs for Railways

Railway telegraphy was very important for managing train traffic and preventing accidents. Cooke and Wheatstone's electric telegraph was first demonstrated for railway use in 1837. It helped operate a system for pulling trains up a hill. The first permanent railway telegraph was completed in 1839.

William Fothergill Cooke proposed the idea of a "block" system in 1842. In this system, a railway line was divided into sections called blocks. Only one train was allowed in a block at a time. Electric telegraphs were used to tell signalmen if a line was clear or blocked. This helped make train travel much safer.

Sending Signals with Flags (Wigwag)

Wigwag was a special way of sending messages using a single flag. It was designed to send signals over very long distances, sometimes up to 32 kilometers (20 miles). Unlike other flag systems, wigwag used motions of the flag rather than fixed positions. This made the signals easier to see from far away.

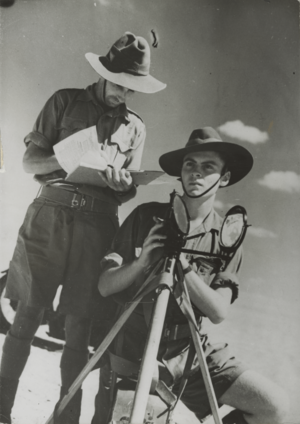

Albert J. Myer, a US Army surgeon, invented wigwag in the 1850s. It was used a lot during the American Civil War. It helped fill gaps where electric telegraph lines had not yet reached. Wigwag stations were set up, some on very tall towers, to create a wide communication network.

Heliographs: Signals from Sunlight

A heliograph is a telegraph that sends messages by flashing sunlight with a mirror. It usually used Morse code. The idea was first suggested in 1821. The first widely used heliograph was invented by Henry Christopher Mance in 1869. It had a movable mirror.

Heliographs were used by the French during the 1870-71 siege of Paris. They even used kerosene lamps at night. British soldiers used improved versions in many wars. A Morse key was later added to make it easier to send messages.

Nelson A. Miles used heliographs extensively in Arizona and New Mexico in the 1880s. He used them during the Apache Wars to communicate across vast, empty areas. A network of 26 stations covered an area of about 320 by 480 kilometers (200 by 300 miles). A message once traveled 640 kilometers (400 miles) in four hours! Heliographs were perfect for the clear air and mountains of the American Southwest.

Heliograph use decreased after 1915. However, British and Commonwealth forces still used them as late as 1942 in World War II.

Machines That Typed Messages (Teleprinters)

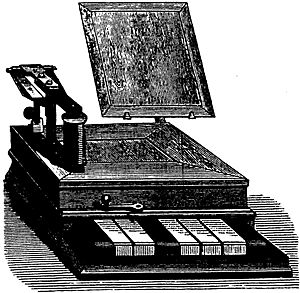

A teleprinter is a telegraph machine that works like a typewriter. You could type a message on a keyboard, and it would print the message at the other end. This meant operators didn't need to know Morse code. Teleprinters helped send messages much faster.

The first true printing telegraph that printed in plain text was invented by Royal Earl House in 1846. Early teleprinters used the Baudot code. This was a five-bit code developed by Émile Baudot in 1874. Unlike Morse code, every character in Baudot code had the same length. This made it easier for machines to use. The Baudot code was also used in early ticker tape machines, which showed stock prices.

Automated Punched-Tape Transmission

With punched-tape systems, a message was first typed onto a paper tape, creating holes that represented the code. This tape could then be fed into a machine to send the message very quickly and steadily. This was especially useful for long, busy routes, as it made the best use of the telegraph lines.

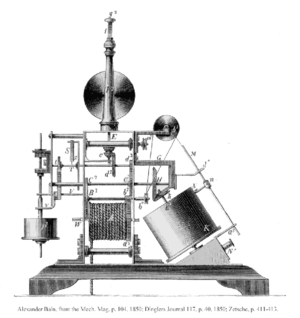

Alexander Bain created the first machine to use punched tape in 1843. Later versions of his system could send up to 1000 words per minute. The Wheatstone system, introduced in 1858, was widely used by the British General Post Office. It could send 400 words per minute.

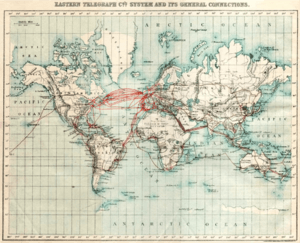

Sending Messages Across Oceans

To create a worldwide communication network, telegraph cables had to be laid across oceans. On land, wires could hang from poles. But underwater, a special insulator was needed that was flexible and could keep seawater out.

The solution was gutta-percha, a natural rubber from a tree. William Montgomerie sent samples to London in 1843. Michael Faraday tested it, and Charles Wheatstone suggested using it for a cable between Dover and Calais. A 3.2-kilometer (2-mile) gutta-percha insulated cable was successfully tested in 1850. The first cable to France was laid in 1850, then relaid in 1851 after being cut. Connections to Ireland and the Netherlands soon followed.

Laying a cable across the Atlantic Ocean was much harder. The Atlantic Telegraph Company tried several times. A cable laid in 1858 worked for a few days but then failed. The company finally succeeded in 1866 with an improved cable. It was laid by the SS Great Eastern, the largest ship of its time.

By 1870, a submarine cable connected Britain to India. Many telegraph companies joined to form the Eastern Telegraph Company in 1872. Australia was linked to the rest of the world by cable in October 1872. From the 1850s, British submarine cable systems were the most important in the world.

Sending Pictures by Telegraph (Facsimile)

In 1843, Scottish inventor Alexander Bain created a device that could send images over electrical wires. He called it a "recording telegraph." Frederick Bakewell improved on Bain's design. In 1855, an Italian priest, Giovanni Caselli, also created an electric telegraph that could send pictures. He called his invention the "Pantelegraph." It was successfully used on a telegraph line between Paris and Lyon.

In 1881, Shelford Bidwell built the first machine that could scan any two-dimensional picture. Around 1900, German physicist Arthur Korn invented the Bildtelegraph. This was widely used in Europe, especially after a famous picture of a wanted person was sent from Paris to London in 1908. These early machines were the ancestors of today's fax machines.

Wireless Telegraphy: Radio Waves!

In the late 1800s, scientists discovered electromagnetic waves, also known as radio waves. Heinrich Rudolf Hertz showed in 1886-1888 that these waves could travel through the air. Many thought these waves would only work over short distances.

However, a young Italian inventor named Guglielmo Marconi began working on a commercial wireless telegraphy system. He improved existing equipment and experimented to extend the range of radio waves. By early 1896, Marconi could send radio signals much farther than expected.

Marconi brought his system to Britain in 1896. He gave demonstrations for the British government. By March 1897, he had sent Morse code signals over 6 kilometers (4 miles). On May 13, 1897, Marconi sent the first wireless signals over water from Flat Holm to Lavernock in Wales. Soon, he was sending signals across the English Channel (1899), from ship to shore (1899), and finally across the Atlantic Ocean (1901). Scientists later discovered the ionosphere, a layer in Earth's atmosphere that reflects radio waves, explaining how signals could travel "over the horizon."

Wireless telegraphy became very important for safety at sea. It allowed ships to communicate with each other and with land. Marconi's equipment helped rescue efforts after the sinking of the RMS Titanic. Britain's postmaster-general said that those saved from the Titanic were saved "through one man, Mr. Marconi...and his marvellous invention."

Early Wireless Experiments

Before radio became successful, many inventors tried other ways to send messages without wires.

Sending Signals Through Ground, Water, and Air

Some people thought electric currents could travel long distances through the ground, water, or air. In 1837, Carl August von Steinheil found he could use the ground as part of an electrical circuit, removing one wire from a telegraph line. This led to ideas about sending signals through the ground without any wires. Samuel F. B. Morse and James Bowman Lindsay experimented with sending currents through water. Lindsay showed he could send messages across a mill dam in 1854.

Nikola Tesla worked on a system in the 1890s to send electricity and telegraph signals through the air and ground. He believed he could use the entire Earth to conduct energy. His large tower, Wardenclyffe Tower, was meant for this, but it ran out of funding. These methods of using ground or water to conduct signals usually only worked over very short distances.

Using Electrostatic and Electromagnetic Induction

Inventors also tried using electrostatic and electromagnetic induction for wireless telegraphy. In the 1880s, Thomas Edison patented an electromagnetic induction system called "grasshopper telegraphy." It allowed telegraph signals to jump short distances between a moving train and wires alongside the tracks. This system was used during the Great Blizzard of 1888 to send messages from snowbound trains. Edison also helped patent a ship-to-shore system using electrostatic induction.

William Preece, a chief engineer in Britain, also developed an electromagnetic induction system. In 1892, he sent messages across gaps of about 5 kilometers (3 miles) over the Bristol Channel. However, his system needed very long antenna wires, sometimes many kilometers long, at both ends. This made it impractical for many uses, especially on ships or small islands.

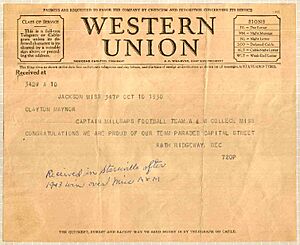

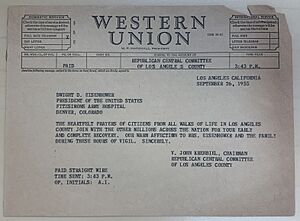

Telegrams: Messages Delivered to Your Door

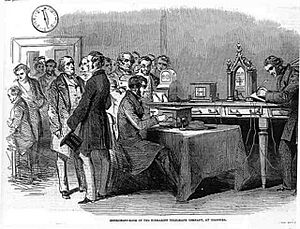

Telegram services began once electric telegraphy was available to the public. Before that, optical telegraphs were mostly for government and military use.

People would go to a local telegraph office and pay by the word to send a message. The message was telegraphed to another office and then delivered to the person on a paper form. Telegrams were faster than regular mail. Even after telephones became common, telegrams remained popular for important personal and business messages. At their peak in 1929, about 200 million telegrams were sent.

In 1919, a special office was set up in New York City to help people register unique code names for their telegraph addresses. This helped make sure messages went to the right person.

Telegram services still exist in some parts of the world today. However, email and text messaging have largely replaced them in many countries. The number of telegrams sent has dropped quickly since the 1980s. Modern telegrams no longer use old telegraph lines; they are sent using telex or the internet.

Telegram Length and Style

Because telegrams were charged by the word, people often made their messages very short. This led to a special way of writing called "telegram style." It meant cutting out unnecessary words to pack as much information as possible into fewer words. In the early 1900s, the average telegram in the US was about 12 words long.

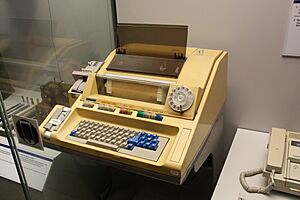

The Rise of Telex

Telex (short for telegraph exchange) was a public network of teleprinters. It worked like an early telephone network, allowing users to dial up other teleprinters to send messages. It first used the Baudot code.

Telex started in Germany in 1926 and became a working service in 1933. It could send messages at about 66 words per minute. Many telex channels could share one telephone line, making it a cheap way to send reliable long-distance messages. Telex came to Canada in 1957 and the United States in 1958. A new code called ASCII was introduced in 1963. ASCII was a seven-bit code that could support more characters, including both uppercase and lowercase letters.

Why Telegraphy Became Less Common

Telegraph use started to decline around 1920. The main reason was the rise of the telephone. The telephone allowed people to talk instantly, which was much faster than sending a telegram. Interestingly, the telephone was invented while people were trying to make telegraphs more efficient.

The Bell Telephone Company started in 1877 with 230 customers. By 1880, it had 30,000. By 1900, there were almost 2 million phones worldwide. While telegram use grew for a while even with telephones, by 1900, the telegraph was clearly becoming less popular.

There was a brief increase in telegraph use during World War I. But the decline continued during the Great Depression in the 1930s. After World War II, new technology improved communication in the telegraph industry. Telegraph lines remained important for news agencies to send news until the internet became popular in the 1990s. For companies like Western Union, sending money (wire transfers) remained a very profitable service, keeping them in business long after telegrams faded. Today, modern digital data transmission and computer systems have replaced the old telegraph.

How Telegraphy Changed the World

Optical telegraph lines were often built by governments for military use. They were usually only for official messages. In many countries, this continued even with electric telegraphs. However, in Britain and the US, railway companies started installing electric telegraph lines. This quickly led to private companies offering telegraph services to the public. This new way of communicating brought big changes to society and the economy.

The electric telegraph made communication much faster than postal mail. It changed how businesses worked and how news traveled. By the late 1800s, more ordinary people were using the telegraph. The telegraph separated the message itself from the physical act of moving an object.

Some people worried about the new technology. They feared it might spread unimportant information. For example, Henry David Thoreau joked that the first news from the Transatlantic cable might be about a princess having whooping cough. These worries are similar to some concerns people have about the internet today.

At first, the telegraph was expensive. But it had a huge impact on three areas: finance, newspapers, and railways. It helped businesses grow and made financial markets more connected. Before the telegraph, the US had many small stock exchanges. The telegraph made it easy to do business from far away, reducing costs and making many of these small exchanges unnecessary. As costs fell, more people started using telegrams.

Worldwide telegraphy changed how news was gathered. Journalists used the telegraph for war reporting as early as 1846 during the Mexican–American War. News agencies, like the Associated Press, were created to report news by telegraph. Messages and information could now travel far and wide. The telegraph also encouraged a more standard way of writing for media, removing local differences in language.

The spread of railways created a need for accurate standard time. Before, each town had its own time based on local noon. The telegraph helped synchronize clocks, leading to the idea of precise time. This also influenced how people thought about the time value of money.

During the telegraph era, many women worked as telegraph operators. In the American Civil War, a shortage of men created opportunities for women to get well-paid, skilled jobs. In the UK, women were employed as operators even earlier, from the 1850s. Companies liked hiring women because they could pay them less than men. Still, these jobs were popular with women because most other work available to them was very poorly paid.

Economists have compared the impact of the electric telegraph to the invention of printing. It was a huge step forward in how information moved around the world.

See also

In Spanish: Telegrafía para niños

In Spanish: Telegrafía para niños

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |