Bletchley Park facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Bletchley Park |

|

|---|---|

The mansion in 2017

|

|

| Type | Codebreaking centre and museum |

| Location | Bletchley, Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Area | 58 acres |

| Built | 1877 (mansion), 1939–1945 (wartime buildings) |

| Original use | Government intelligence site |

| Current use | Bletchley Park Museum |

| Owner | Bletchley Park Trust |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

Bletchley Park is a famous country estate in Bletchley, England. During World War II, it became the top-secret headquarters for Allied code-breaking. This is where brilliant minds worked to crack the secret messages of the Axis Powers, especially Germany's Enigma and Lorenz ciphers.

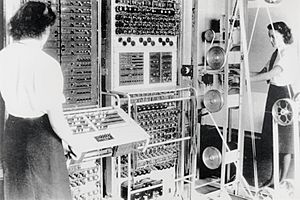

The team at Bletchley Park, which included many women, created amazing machines to help them. One of these was the Colossus, the world's first programmable digital electronic computer. The code-breaking work stopped in 1946. All information about their wartime operations was kept secret for many years. Today, Bletchley Park is a museum where you can learn about its incredible history.

Contents

- The Bletchley Park Estate: Before the War

- Bletchley Park in World War II

- Bletchley Park Today: A Legacy of Secrecy and Innovation

- See also

The Bletchley Park Estate: Before the War

The estate was first called Bletchley Park in 1877. Sir Herbert Samuel Leon bought it in 1883 and made the house much bigger. It became a mix of different building styles, like Victorian Gothic and Tudor.

After Sir Herbert Leon's wife passed away in 1937, the estate was almost sold for new houses. But in 1938, Admiral Sir Hugh Sinclair, who led Britain's secret intelligence service (MI6), bought it. He wanted to use it as a secret base if war broke out.

Bletchley Park in World War II

Bletchley Park played a huge role in World War II. It was where the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) worked to break enemy codes.

Getting Ready for War

Admiral Sinclair chose Bletchley Park because of its great location. It was right next to Bletchley railway station. This station connected Oxford and Cambridge universities, where many future code-breakers would come from. Major roads and communication lines were also nearby. Sinclair even used his own money to buy the park when the government said they couldn't afford it.

Just five weeks before the war began, Polish code-breakers shared their amazing success in breaking the Enigma code. This information and the special Enigma machine they sent helped the British team a lot.

Early Days of Code-Breaking

The first code-breakers moved into Bletchley Park on August 15, 1939. Different sections, like Naval, Military, and Air, were set up in the mansion. Soon, wooden huts were built to hold more workers and equipment.

The site was only hit by enemy bombs once, in November 1940. The bombs were likely aimed at the nearby railway station. One hut was moved two feet off its foundation, but work inside continued!

Churchill's "Action This Day"

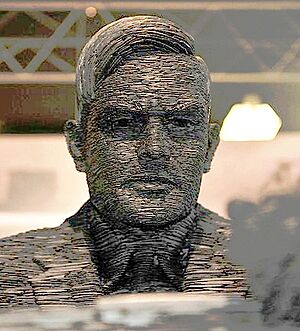

By 1941, the code-breakers needed more staff and resources to keep up with the work. Four key code-breakers, including Alan Turing, wrote directly to Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Churchill's famous response was: "Action this day make sure they have all they want on extreme priority." This meant their needs were top priority.

Working with Allies

After the United States joined World War II, American code-breakers came to Bletchley Park. From 1943, Britain and America worked closely together. This partnership was a big step towards the "Five Eyes" intelligence alliance we know today.

However, the Soviet Union was never officially told about Bletchley Park. Churchill didn't trust the Soviets, even though they were allies against Nazi Germany. A Soviet spy named John Cairncross did manage to leak some secrets from Bletchley Park to Moscow.

The People of Bletchley Park

Many different kinds of people worked at Bletchley Park. Early recruits included linguists and chess champions. The British War Office even looked for people who were good at solving cryptic crossword puzzles. These people often had strong problem-solving skills.

As the war went on, more mathematicians were needed to tackle complex cipher machines. Famous mathematicians like Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman joined the team. Many women also played vital roles. They came from various backgrounds, including those with degrees in math, physics, and engineering. They performed calculations and coding, which was essential for the computing processes.

Some of the women were called "Dilly's Fillies" after their section leader, Dilly Knox. Mavis Lever and Margaret Rock were two of these women who helped solve a German code. Other women, like Jane Fawcett, translated decoded German Navy signals. She even decrypted a crucial message about the German battleship Bismarck.

At its busiest in January 1945, nearly 9,000 people worked at Bletchley Park and its smaller sites. About three-quarters of them were women.

Keeping Secrets

The German Enigma and Lorenz ciphers were supposed to be almost impossible to break. But mistakes in German procedures created weaknesses that Bletchley Park exploited. If Germany had known about Bletchley's success, they would have fixed these flaws. So, the intelligence gathered was called the "Ultra secret," even more secret than "Most Secret."

Everyone working at Bletchley Park signed the Official Secrets Act. They were constantly reminded not to talk about their work, even with friends or family. "Do not talk at meals. Do not talk in the transport. Do not talk travelling. Do not talk in the billet. Do not talk by your own fireside. Be careful even in your Hut..."

Despite the strict rules, some secrets did get out. But overall, the work remained hidden for decades. Bletchley Park was known as "B.P." to those who worked there. Other secret names included "Station X" and "London Signals Intelligence Centre."

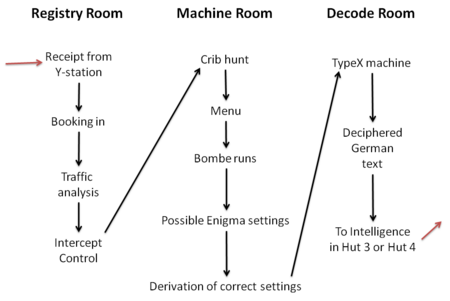

Deciphered messages were sent to different "Huts" for translation and analysis. For example, Hut 3 handled Army and Air Force messages, while Hut 4 and Hut 8 focused on Naval messages. These Huts would then send important intelligence reports to military leaders.

Listening Stations

Bletchley Park had its own wireless room, called "Station X," in the mansion's water tower. But because the long radio aerials might draw attention, the radio station moved to nearby Whaddon Hall.

Other listening stations, called "Y-stations," were set up across the country. They intercepted raw coded messages. These messages were written down by hand and sent to Bletchley Park by motorcycle riders or teleprinter.

Buildings at Bletchley Park

As the war continued, more buildings were needed. These included wooden "Huts" and brick "Blocks."

The Huts

Each hut had a specific job, and its number became famous for that work.

- Hut 1: First used for the Wireless Station, then for things like transport and machine maintenance.

- Hut 2: A place for workers to relax and get refreshments.

- Hut 3: Translated and analyzed Army and Air Force secret messages.

- Hut 4: Analyzed Naval Enigma and other naval codes.

- Hut 5: Worked on Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and German police codes.

- Hut 6: Focused on breaking Army and Air Force Enigma codes.

- Hut 7: Worked on Japanese naval codes.

- Hut 8: Focused on breaking Naval Enigma codes.

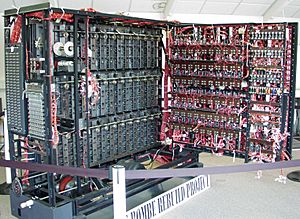

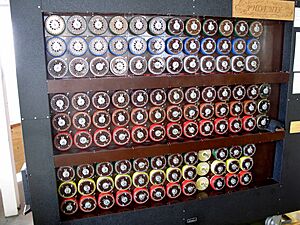

- Hut 11: Housed the Bombe machines.

- Hut 23: Later became the new home for Hut 3's work.

The Blocks

Brick buildings, called "Blocks," were also built.

- Block C: Stored huge amounts of information on punch-cards.

- Block D: Housed teams that combined intelligence from many sources.

- Block H: Home to the "Tunny" (Lorenz cipher) and Colossus computers. Today, it houses The National Museum of Computing.

Breaking German Codes

Most German messages were made using the Enigma cipher machine. But some very important messages used the more complex Lorenz SZ42 machine, nicknamed "Fish."

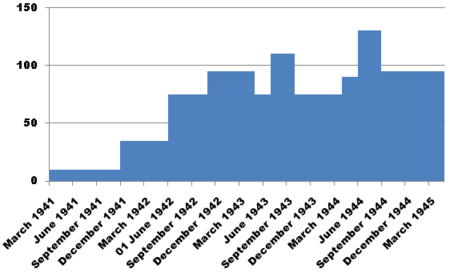

The bombe was an electro-mechanical machine designed by Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman. Its job was to figure out the daily settings of the Enigma machines. Each Bombe was huge, about 7 feet tall and wide, and weighed a ton!

At its busiest, Bletchley Park was reading about 4,000 German messages every day. This work was vital for winning the Battle of the Atlantic against German U-boats. It also helped the Allies prepare for D-Day in 1944, knowing where most German divisions were located.

The Lorenz messages, called Tunny at Bletchley Park, were used for high-level communications. To break these, the team developed the Colossus. This was the world's first programmable digital electronic computer, designed by Tommy Flowers. The first Colossus started working in February 1944, just in time for D-Day. Ten Colossus machines were built during the war.

Breaking Italian Codes

Italian signals also interested the code-breakers. In 1941, Mavis Lever solved signals that revealed the Italian Navy's plans before the Battle of Cape Matapan. This led to a big British victory.

Another code-breaker, Bernard Willson, decoded the Italian Hagelin system. This helped military commanders direct the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force to sink enemy ships carrying supplies to German forces in North Africa.

Breaking Japanese Codes

A British code-breaking outpost in Hong Kong, called the Far East Combined Bureau (FECB), worked on Japanese codes. During the war, this team moved to different locations, including Singapore and Kenya.

In 1942, special Japanese language courses were set up for university students. Many of these students then worked in Hut 7 at Bletchley Park, decoding Japanese naval messages.

Bletchley Park Today: A Legacy of Secrecy and Innovation

After the war, the code-breaking school became the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). It moved to a new location in 1946.

The Secret Revealed

For many years, the work done at Bletchley Park remained a secret. Most people who worked there couldn't even tell their families what they did. Prime Minister Churchill famously called them "the geese that laid the golden eggs and never cackled."

It wasn't until 1974, with the publication of The Ultra Secret by F. W. Winterbotham, that the public finally learned about Bletchley Park's incredible achievements. In 2009, the British government officially recognized the contributions of everyone who worked there with a special commemorative medal.

Saving Bletchley Park

Over the years, parts of the Bletchley Park site were used for different things, and some buildings were even torn down. In 1991, a group of people realized how important the site was and formed the Bletchley Park Trust. They wanted to save it from being sold for housing.

The site opened to visitors in 1993 and became a museum. In 2014, a big restoration project was completed. Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge, visited to mark the occasion. Her own grandmother and great-aunt had worked as code-breakers in Hut 6 during the war!

Today, the Bletchley Park Learning Department offers educational visits for schools and universities. Students can learn about code-breaking, cyber security, and the stories of Enigma and Lorenz.

The National Museum of Computing

The National Museum of Computing is located in Block H at Bletchley Park. It's a separate museum that tells the story of computing. You can see a working reconstruction of a Bombe machine and a rebuilt Colossus computer there. The museum aims to collect and restore computer systems, especially those developed in Britain. Many of its exhibits are in full working order, so you can see them in action!

See also

In Spanish: Bletchley Park para niños

In Spanish: Bletchley Park para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |