Alan Turing facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alan Turing

|

|

|---|---|

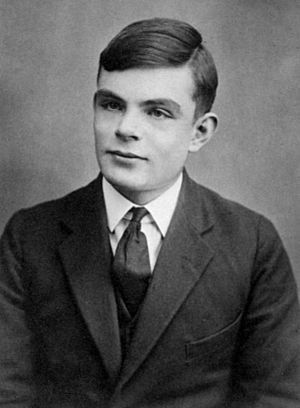

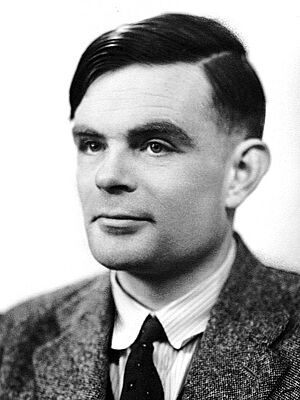

Turing in 1951

|

|

| Born |

Alan Mathison Turing

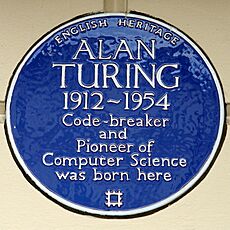

23 June 1912 Maida Vale, London, England

|

| Died | 7 June 1954 (aged 41) Wilmslow, Cheshire, England

|

| Alma mater | |

| Known for |

|

| Awards | Smith's Prize (1936) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | Systems of Logic Based on Ordinals (1938) |

| Doctoral advisor | Alonzo Church |

| Doctoral students |

|

| Signature | |

Alan Mathison Turing (born 23 June 1912, died 7 June 1954) was a brilliant English mathematician and computer scientist. He is often called the 'father of theoretical computer science' because his ideas helped create the computers we use today. He invented the 'Turing machine,' a model for how computers work, and played a huge role in winning World War II.

Turing was born in London and grew up in southern England. He studied at King's College, Cambridge, and later earned a doctorate from Princeton University. During World War II, he worked at Bletchley Park, Britain's secret codebreaking center. He led a team that cracked German codes, especially those from the Enigma machine. This work was vital for the Allies to win important battles.

After the war, Turing helped design one of the first computers that could store programs. He also explored how patterns form in nature, like the spots on animals. Despite his amazing achievements, much of his work was kept secret for many years.

Later in his life, Alan Turing faced unfair legal challenges because of outdated laws. These challenges led to difficult treatments and a sad end to his life at just 41 years old. There are different ideas about how he died, but many believe it was a tragic accident. In 2009, the British government apologized for how he was treated. In 2013, Queen Elizabeth II granted him a pardon. A law passed in 2017, known as the "Alan Turing law," pardoned many others who were treated unfairly under similar old laws.

Turing left behind an incredible legacy in mathematics and computing. Many things are named after him, including a major award for computer innovation. His picture is even on the Bank of England £50 note.

Contents

Alan Turing's Early Life and Education

His Family and Childhood

Alan Turing was born in Maida Vale, London, on 23 June 1912. His father worked for the British government in India. His parents wanted their children to grow up in Britain. So, they often traveled between the UK and India. Alan and his older brother, John, stayed with a retired Army couple during these times.

When Alan was young, he discovered a book called Natural Wonders Every Child Should Know. He later said this book sparked his interest in science. In 1927, his parents bought a house in Guildford, where Alan spent his school holidays.

School Days and Discoveries

From age six to nine, Alan attended St Michael's, a primary school. His headmistress quickly saw his special talent. She called him a "genius."

At 13, he went to Sherborne School, a boarding school. On his first day, there was a big strike in Britain. But Alan was so determined to get to school that he rode his bicycle 60 miles (about 97 km) all by himself!

Some teachers at Sherborne didn't appreciate his love for math and science. They thought he should focus more on traditional subjects. But Alan kept showing amazing skill in what he loved. By age 16, he was already understanding Albert Einstein's complex ideas.

A Special Friendship

At Sherborne, Alan became very good friends with another student, Christopher Morcom. Christopher was a brilliant and kind companion. Their friendship inspired Alan in his studies. Sadly, Christopher died in 1930 from an illness.

Alan was very sad about losing his friend. He dealt with his grief by working even harder on science and math, subjects they had shared. He wrote to Christopher's mother, saying he would put as much energy into his work as if Christopher were still alive. Alan's connection with Christopher's mother continued for many years.

University Studies and Computer Ideas

After Sherborne, Alan earned a scholarship to King's College, Cambridge. He studied mathematics there and graduated with top honors. In 1935, he became a Fellow of King's College.

Between 1935 and 1936, Alan worked on important ideas about how problems can be solved. He wrote a famous paper called "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem". In this paper, he introduced the idea of the "Turing machine." This was a simple, imaginary device that could perform any mathematical calculation if it was given clear instructions. It became a model for how all modern computers work.

His idea of a "Universal Machine" meant that one machine could do the job of any other computing machine. This concept is central to how computers work today. From 1936 to 1938, Alan studied at Princeton University in the United States, where he earned his PhD. He also built parts of an early electronic calculator.

Alan Turing's Career and Research

Codebreaking During World War II

During World War II, Alan Turing played a leading role in cracking German secret codes at Bletchley Park. This secret location was Britain's center for codebreaking. Historians say his genius was essential to their success.

From 1938, Turing worked part-time with the British codebreaking organization. He focused on the Enigma machine, which was used by Nazi Germany to send secret messages. After learning about the Enigma from Polish codebreakers, Turing and his colleagues developed new ways to break its codes.

On 4 September 1939, the day after Britain declared war on Germany, Turing started working full-time at Bletchley Park. He had to sign the Official Secrets Act, promising never to tell anyone about his work.

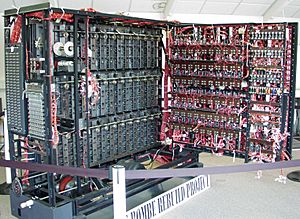

Turing made five major breakthroughs in codebreaking during the war. One of his most important inventions was the "bombe." This was an electromechanical machine that helped find the settings for the Enigma machine much faster. He also developed statistical methods like Banburismus to make codebreaking even more efficient.

By late 1941, Turing and his team needed more resources. They wrote directly to Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Churchill quickly ordered that they receive all the help they needed. This led to more than two hundred bombes being built by the end of the war.

Turing also tackled the difficult problem of cracking the German navy's Enigma codes. He developed Banburismus, a clever statistical technique that helped reduce the time needed to test Enigma settings. His work was so important that it helped the Allies defeat the Axis powers in key battles, like the Battle of the Atlantic.

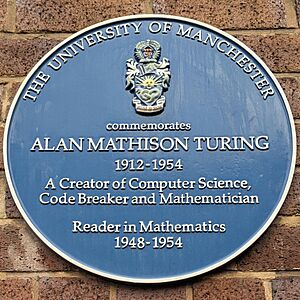

Historians believe Turing's work shortened the war in Europe by more than two years. For his wartime services, he was awarded the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1946. However, his work remained secret for many years due to the Official Secrets Act.

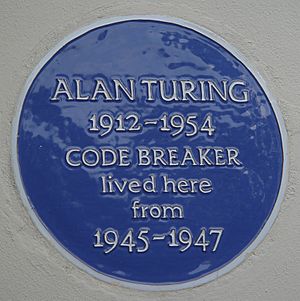

Early Computers and the Turing Test

From 1945 to 1947, Turing worked on designing the ACE (Automatic Computing Engine) at the National Physical Laboratory. This was one of the first detailed designs for a computer that could store its own programs.

In 1948, Turing became a professor at the University of Manchester. He worked on software for one of the earliest computers, the Manchester Mark 1. He also became interested in artificial intelligence.

In his paper "Computing Machinery and Intelligence," Turing proposed an experiment called the Turing test. This test tries to figure out if a machine can "think." The idea is that if a human can't tell if they are talking to a computer or another human, then the computer might be considered intelligent. A reversed version of this test, called CAPTCHA, is used today to check if a user is human or a computer.

Turing also started writing a chess program for a computer that didn't even exist yet. He called it the Turochamp. In 1952, he tried to run it on a computer, but it wasn't powerful enough. So, Turing "ran" the program himself by following its instructions on a chessboard.

Pattern Formation in Nature

In 1951, Alan Turing began studying mathematical biology. He published a famous paper called "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis" in 1952. He was curious about how patterns and shapes develop in living things.

He suggested that a system of chemicals reacting and spreading out could explain how patterns form. For example, this could explain the spots and stripes on animal fur. His work used complex math to show how these patterns could appear. Even though he published this before we fully understood DNA, his ideas are still very important in mathematical biology today.

Alan Turing's Personal Life

Hidden Treasure

In the 1940s, Alan Turing worried about his savings if Germany invaded Britain. He bought two silver bars and buried them in a wood near Bletchley Park. When he returned to dig them up, he couldn't remember exactly where he had hidden them! He never found his silver again.

An Engagement

In 1941, Turing proposed marriage to Joan Clarke, a fellow mathematician and codebreaker at Hut 8. However, their engagement was short-lived. Turing realized that marriage was not the right path for him, and they decided not to marry.

Chess Fun

Turing invented a fun, unusual chess game called round-the-house chess. In this game, one player makes a move, then runs around the house. The other player must make their move before the first player returns!

A Difficult Time and His Death

In 1952, Alan Turing faced legal difficulties due to laws that are now considered unfair and outdated. These challenges led to a difficult period in his life. He accepted certain treatments as an alternative to prison.

Alan Turing died on 7 June 1954, at his home in Wilmslow, at the age of 41. When his body was found, a half-eaten apple lay beside his bed. While the apple was never tested, it was thought to be connected to his death.

There are different ideas about how he died. An official investigation concluded it was a tragic event. However, some people believe it might have been an accident, perhaps from inhaling fumes from a science experiment he was working on. His mother always believed his death was accidental.

Historians and biographers have discussed these different theories. Some suggest he might have been inspired by a scene from his favorite fairy tale, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Government Apology and Pardon

In 2009, many people signed a petition asking the British government to apologize for how Alan Turing was treated. Prime Minister Gordon Brown issued an official public apology on 10 September 2009. He called Turing's treatment "appalling" and said, "we're sorry, you deserved so much better."

In 2011, another petition asked the government to officially pardon Turing. This petition gathered over 37,000 signatures. Many scientists, including Stephen Hawking, supported the request.

On 24 December 2013, Queen Elizabeth II officially granted Alan Turing a pardon for his conviction. Announcing the pardon, Lord Chancellor Chris Grayling said Turing deserved to be "remembered and recognised for his fantastic contribution to the war effort."

In 2016, the government announced a plan to pardon other men who were treated unfairly under similar old laws. This became known as the "Alan Turing law." This law, passed in 2017, officially pardoned thousands of men who had faced similar injustices.

In 2023, Defence Secretary Ben Wallace suggested that Turing should be honored with a permanent statue in Trafalgar Square. He described Turing as "probably the greatest war hero... of the Second World War."

Alan Turing Quotes

- "A man provided with paper, pencil, and rubber, and subject to strict discipline, is in effect a universal machine."

- "Science is a differential equation. Religion is a boundary condition."

- "We can only see a short distance ahead, but we can see plenty there that needs to be done."

- "It is customary... to offer a grain of comfort, in the form of a statement that some peculiarly human characteristic could never be imitated by a machine. ... I cannot offer any such comfort, for I believe that no such bounds can be set."

- "Machines take me by surprise with great frequency."

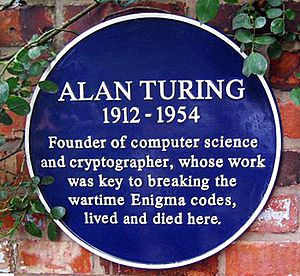

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Alan Turing para niños

In Spanish: Alan Turing para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |