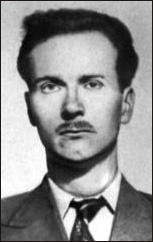

John Cairncross facts for kids

Quick facts for kids John Cairncross |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Allegiance | Soviet Union |

| Service | Foreign Office The Government Code and Cypher School, Bletchley Park |

| Codename(s) | Liszt |

|

|

|

| Born | 25 July 1913 Lesmahagow, Lanarkshire, Scotland |

| Died | 8 October 1995 (aged 82) Herefordshire, England |

| Spouse |

|

| Alma mater | University of Glasgow The Sorbonne Trinity College, Cambridge |

John Cairncross (born July 25, 1913 – died October 8, 1995) was a British government worker. He became a spy for the Soviet Union during World War II. He secretly shared important information with the Soviets. This information helped them win major battles against Germany.

Cairncross was thought to be the fifth member of a famous spy group called the Cambridge Five. He also worked as a translator and writer. He secretly admitted to being a spy in 1964. Later, in 1979, he spoke to journalists about it. He was not charged with any crime for his spying.

His role as the "fifth man" was confirmed in 1990 by a former Soviet spy, Oleg Gordievsky. Another former Soviet agent, Yuri Modin, also confirmed this in his 1994 book.

Contents

Early Life and School

John Cairncross was born in Lesmahagow, Scotland. He was the youngest of eight children. His mother was a teacher and his father managed a hardware store.

Three of his brothers became university professors. One of them was the famous economist Sir Alexander Kirkland Cairncross. John grew up in Lesmahagow, a small town near Lanark.

He went to Lesmahagow Higher Grade School, where he won a top student award in 1928. He then studied at Hamilton Academy, the University of Glasgow, the Sorbonne in Paris, and Trinity College, Cambridge. At Cambridge, he studied French and German.

Starting His Career

After finishing university, John Cairncross took a difficult government exam. He came in first place for both the "home civil service" (working in Britain) and the "foreign office and diplomatic service" (working abroad). This was a big achievement.

He first worked in the British Foreign Office, which deals with other countries. Then he moved to the Treasury, which handles money matters. Later, he worked for Lord Hankey in the Cabinet Office.

It is thought that Cairncross joined the Communist Party while at Cambridge. However, his brother Alec, who was also at Cambridge, did not notice any political activity from John. Alec remembered John as a "prickly young man" who could be difficult.

Around 1936, while working for the Foreign Service, he was recruited to spy for the Soviets. A man named James Klugmann from the Communist Party of Great Britain recruited him.

World War II Spy Work

During World War II, John Cairncross worked at Bletchley Park. This was a secret place where British experts broke German codes. He worked in "Hut 3," which dealt with ULTRA codes. This meant he had access to secret messages from the German military.

In June 1943, he left Bletchley Park to work for MI6, Britain's foreign intelligence service.

Secret Messages from Bletchley Park

Cairncross secretly passed decoded German documents to the Soviet Union. The Russians gave him the codename Liszt because he loved music. They had told him to get a job at Bletchley Park, which they called Kurort.

From 1942, the German High Command used a special machine called Tunny to talk to their army groups. Cairncross would sneak Tunny decryptions out of Bletchley Park. He would hide them in his trousers and then move them to his bag at the train station. He would then meet his Soviet contact in London.

The Soviets were very interested in these messages. They wanted to know about German plans and movements. Cairncross's actions showed the Soviets that the British were able to break German codes.

It was helpful for the Soviets to know German plans, but the British didn't want them to know how they got the information. This was because the Soviet Union's security was not very good. At first, the Soviets thought the information was a trick because it was so good. But they used it and found it to be true.

Helping at the Battle of Kursk

One of the most important things Cairncross did was provide information about "Operation Citadel." This was the German plan for a huge attack that led to the Battle of Kursk. The Battle of Kursk was a major turning point in World War II. After losing this battle, the German army began to retreat.

The Tunny decryptions gave the British early warnings about Operation Citadel. Cairncross provided these raw, secret messages directly to the Soviets. This helped the Soviets prepare for the German attack.

Information on Yugoslav Partisans

Axis forces (Germany and its allies) in Yugoslavia used radio to communicate a lot. Bletchley Park intercepted and decoded these messages. They also decoded messages between Yugoslav fighters (called partisans) and the Soviet Union. Cairncross had access to these secret messages. He likely passed information about Yugoslavia to the Soviets as well.

Working as a Spy

Between 1941 and 1945, Cairncross gave the Soviets 5,832 documents. This number comes from Russian records. In 1944, he joined MI6, the British foreign intelligence service. He worked in the counter-intelligence section. He helped create a list of the German SS forces. Cairncross later said he didn't know that his boss, Kim Philby, was also a Soviet spy.

In October 1944, he wrote to his Soviet contacts. He said he was happy his help was useful and proud to have contributed to the Soviet victory. In March 1945, he was offered a yearly payment of £1,000, but he turned it down.

A Russian spy controller, Yuri Modin, claimed Cairncross gave him details about nuclear weapons. These weapons were supposedly going to be placed with NATO in West Germany. However, there were no such plans at that time. This information might have been a trick to mislead the Soviets.

In 1951, British counterintelligence questioned Cairncross. They asked about his connection to another spy, Donald Maclean, and the Communist Party. Cairncross had been taught by the Soviets how to act during questioning. He told the interrogator that he didn't hide his party membership. He also said he only greeted Maclean at work and didn't keep in touch with him after university.

Cairncross admitted to some wrongdoing in 1951. This happened after MI5 found papers with his handwriting in another spy's apartment. The official report said there wasn't enough proof to charge him with spying at that time.

Evidence from Soviet records shows that Cairncross gave early information about Britain's plans to develop atomic weapons. In 1940, he worked for Maurice Hankey, who was on committees discussing atomic weapons. While he didn't give technical details, he let the Soviets know Britain was thinking about making atomic bombs. He was never charged, which led some to believe the government tried to hide his role.

The identity of the "fifth man" in the Cambridge Five was a secret for a long time. It wasn't until 1990 that Oleg Gordievsky, a KGB spy who switched sides, publicly confirmed it was Cairncross. Cairncross worked mostly on his own. He didn't come from the same wealthy background as the other four spies. He knew some of them but claimed he didn't know they were also spying for Russia.

Cairncross left his government job in 1952 and lost his pension. In 1964, he admitted to an investigator named Arthur Martin that he had spied for the Soviets.

In December 1979, a journalist named Barrie Penrose approached Cairncross. Cairncross confessed to him, and the news became widely known. This made many people believe he was the "fifth man," which was later confirmed in 1989.

Cairncross didn't see himself as part of the Cambridge Five. He believed the information he sent to Moscow didn't harm Britain. He felt he was helping an ally (the Soviet Union) who was being denied information by a "right-wing group." Some historians agree that his most important spy work ended with World War II. Unlike the other Cambridge spies, who were from wealthy families, Cairncross was from a working-class background.

Later Life

After the war, Cairncross worked for the Treasury. He said he stopped working for the Soviet intelligence agency (MGB, later KGB) at this time. However, later KGB reports said he continued to work for them.

After his first confession in 1952, Cairncross lost his government job. He had no money and no work. With some help from his former Soviet contact, he moved to the United States. There, he taught at universities in Chicago and Cleveland, Ohio. Cairncross was an expert on French writers. He translated many works by famous 17th-century French poets and playwrights. He also wrote three of his own books.

His teaching career ended after more investigations by MI5. In 1964, Cairncross fully confessed to investigator Arthur Martin. Even though he confessed, he was never charged with spying. His confession was made in the US and couldn't be used in a British court. MI5 asked him to return to Britain to confess again, but he refused.

In 1967, Cairncross moved to Rome, Italy. He worked as a translator for the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. He also did work for banks. In 1970, he moved to France.

In December 1979, his secret became public. A former government worker hinted to a journalist that there was another spy in the Foreign Office. The journalist figured out it was Cairncross and confronted him.

Cairncross's confession became front-page news. In 1981, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher told the British Parliament that Cairncross was a Soviet agent. She said he was living in England and writing his memoirs. His role as the "fifth man" was confirmed in 1990.

Cairncross retired to the south of France. In 1995, he returned to Britain and married Gayle Brinkerhoff. This was one month after his first wife, Gabriella Oppenheim, died. Later that year, he died at age 82 after having a stroke.

Unlike many other spies, Cairncross was never put in jail for spying. He was once jailed in Rome for issues involving money, but not for being a spy.

Cairncross's autobiography, The Enigma Spy, was published in 1997. In the book, he denied being the "fifth man" and even said such a person didn't exist. Many critics felt the book was his last attempt to clear his name.

In Books and Movies

John Cairncross has been shown in several TV shows and movies:

- In the 2003 BBC TV series Cambridge Spies, he is shown as not wanting to give Bletchley Park information to the Russians. He was worried German spies had gotten into the Red Army.

- He appears in the comic book India Dreams.

- He is shown as the fifth of the Cambridge Five in Frederick Forsyth's novel The Deceiver.

- In the 2014 film The Imitation Game, Cairncross is played by Allen Leech. He is shown as a codebreaker at Bletchley Park. The movie suggests he was an unknowing double agent used by MI6 to pass information to the Soviets. However, historians and Cairncross's own book confirm he spied for the Soviets because of his own beliefs. MI6 didn't find out until much later.

Awards

- Order of the Red Banner: This award was given to him for successfully getting information about German plans and operations during World War II.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |