Claude Chappe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Claude Chappe

|

|

|---|---|

Claude Chappe

|

|

| Born | 25 December 1763 |

| Died | January 23, 1805 (aged 41) Paris, France

|

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Engineering career | |

| Projects | semaphore system |

| Significant advance | telecommunications |

Claude Chappe (French: [klod ʃap]; 25 December 1763 – 23 January 1805) was a French inventor. In 1792, he showed off a working semaphore system. This system eventually spread across all of France.

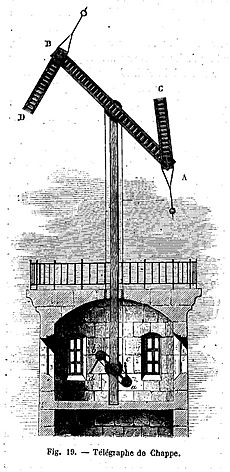

His invention used a series of towers. Each tower could be seen from the next one. On top of each tower was a wooden pole with two moving arms. An operator in one tower would move these arms into different positions. These positions spelled out messages using a special code. The operator in the next tower would read the message with a telescope. Then, they would send it on to the next tower.

This was the first useful telecommunications system of the industrial age. It was used until the 1850s. That's when electric telegraph systems took its place.

Contents

Claude Chappe's Early Life

Claude Chappe was born in Brûlon, Sarthe, France. His father, Ignace Chappe, managed royal lands for Laval. His mother, Marie Devernay, was the daughter of a physician. Claude was meant to work for the church. But he lost his position during the French Revolution. He went to school at the Lycée Pierre Corneille in Rouen.

His uncle was Jean-Baptiste Chappe d'Auteroche, a famous astronomer. His uncle was known for watching the Transit of Venus in 1761 and 1769. Claude's brother, Abraham, said that reading his uncle's travel journal inspired Claude. It made him interested in science. Claude's connection to his astronomer uncle might have also taught him about telescopes.

Claude and his four brothers were all out of work. They decided to create a useful system of semaphore stations. People had thought about this idea for a long time, but no one had made it work.

Claude's brother, Ignace Chappe, was a member of the Legislative Assembly. With his help, the Assembly agreed to build a telegraph line. This line would go from Paris to Lille. It was about 120 miles long and had fifteen stations. It was meant to send messages about the war.

How the Telegraph Worked

The Chappe brothers found that angles of a rod were easier to see than panels. Their final design had two arms connected by a cross-arm. Each arm could be in seven positions. The cross-arm had four more positions. This allowed for 196 different code combinations. The arms were from three to thirty feet long. They were black and had weights to balance them. Only two handles were needed to move them. Lamps on the arms did not work well for night use.

The relay towers were placed about 10 to 20 miles apart. Each tower had a telescope. Operators used it to see towers both up and down the line.

Chappe first called his invention a tachygraph, meaning "fast writer." But the Army preferred the word telegraph, meaning "far writer." This word was created by French statesman André François Miot de Mélito. Today, Chappe's system is called the Telegraph Chappe in French. This helps tell it apart from later electric telegraphs. Chappe also created the word semaphore. It comes from Greek words meaning "sign" and "carrying."

Impact and Legacy

In 1792, the first messages were successfully sent between Paris and Lille. In 1794, the semaphore line quickly told Parisians about the capture of Condé-sur-l'Escaut. This happened less than an hour after the event. More lines were built, including one from Paris to Toulon. Other European countries copied the system. Napoleon used it to manage his empire and army.

Claude Chappe faced challenges, including illness and claims from rivals. These rivals said he had copied ideas from military semaphore systems.

In 1824, Ignace Chappe tried to get people interested in using the semaphore line for business messages. For example, he wanted to send prices of goods. However, businesses were not interested.

From 1844, the French government started testing new electric telegraph lines. They decided to fully replace the Chappe telegraph by 1846. Many people worried that electric wires could be easily cut or damaged. Because the French optical telegraph system was so large, it took some time to replace it. Both systems were used at the same time for about ten years. One of the last messages sent by the Chappe telegraph was news of the fall of Sevastopol in 1855.

In Popular Culture

The Chappe semaphore system is an important part of Alexandre Dumas' book The Count of Monte Cristo. In the story, the Count pays an operator to send a false message.

Memorials

Rue Chappe, a street in Paris, is named after Chappe. A bronze statue of him was put up in Paris. However, during the Nazi occupation of Paris in 1941 or 1942, this statue was removed and melted down.

See also

In Spanish: Claude Chappe para niños

In Spanish: Claude Chappe para niños

- Chappe code

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |