Pavel Schilling facts for kids

Baron Pavel Lvovitch Schilling (1786–1837), also known as Paul Schilling, was a Russian military officer and diplomat. He was of Baltic German background. Most of his career was spent working for the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He worked as a language officer at the Russian embassy in Munich. As a military officer, he fought in the War of the Sixth Coalition against Napoleon. Later, he moved to the Asian department of the ministry. He traveled to Mongolia to collect old manuscripts.

Schilling is most famous for his groundbreaking work in electrical telegraphy. He started this work on his own. While in Munich, he worked with Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring. Sömmerring was developing an electrochemical telegraph. Schilling then created the first useful electromagnetic telegraph. Schilling's design was a needle telegraph. It used magnetized needles hanging by a thread over a coil carrying electricity. His design also used much fewer wires than Sömmerring's system. This was done by using binary coding. Tsar Nicholas I planned to install Schilling's telegraph. It was meant to connect to Kronstadt. But the project was canceled after Schilling died.

Schilling was also interested in other technologies. These included lithography and remotely setting off explosives. For explosives, he invented a special underwater cable. He later used this cable for his telegraph as well. After Schilling's death, his assistant, Moritz von Jacobi, continued his work on telegraphy in Russia. Jacobi also worked on other electrical uses.

Pavel Schilling's Life Story

Early Years and Education

Baron Pavel Lvovitch Schilling von Cannstadt was born in Reval (now Tallinn), Estonia. His birthday was April 16, 1786. He was of German descent. When Pavel was young, his family moved to Kazan. He spent his childhood there. Being around different Asian cultures made him interested in the East. He was expected to join the military like his father. So, at age nine, he formally joined the Nizovsky regiment. After his father died, he was sent to the First Cadet Corps. He started his proper military training in 1802. He became a second lieutenant. He was assigned to map-making duties.

In 1803, Schilling left the military. He joined the foreign service as a language officer. He was sent to the Russian embassy in Munich. His stepfather, Karl von Bühler, was the minister there. From 1809 to 1811, Schilling served as an attaché in Munich. He first became interested in electrical science in Munich. This was through his contact with Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring. Sömmerring was developing an electrical telegraph. Schilling spent a lot of time with Sömmerring. He brought many Russian officials to see Sömmerring's device.

Fighting in the Napoleonic Wars

When war between France and Russia seemed likely, Schilling thought about using his electrical knowledge for military purposes. In July 1812, he was called back to Saint Petersburg. This was because of the upcoming French invasion of Russia. He brought a complete Sömmerring telegraph with him. He showed it to military engineers and Tsar Alexander I. He continued working on remotely setting off mines. However, none of his inventions were ready for battle. Schilling asked to be transferred to a military position in the fighting army.

It was not easy to place Schilling in the military. He had no combat experience. As a retired officer, he was only a second lieutenant. But as a civil servant, he had reached a higher rank. In May 1813, he asked Alexander I directly for a military role. He was assigned to the horse artillery reserves. He joined the 3rd Sumskoy dragoons in September 1813. Schilling arrived at the regiment after the Battle of Dresden. He worked as a contact person with Saxon authorities. He did not see real combat until December 1813. This was when Russian troops moved into French territory. He received his first award for the Battle of Bar-sur-Aube in February 1814. His actions during the Battle of Arcis-sur-Aube and the Battle of Fère-Champenoise earned him the Golden Weapon for Bravery.

Returning to Diplomatic Work

After the fall of Paris in 1814, Schilling asked to return to civil service. In October, he went back to the Foreign Affairs Ministry in Saint Petersburg. Russia's foreign policy after the war focused on expanding eastward. So, Schilling was placed in the growing Asiatic Department. He continued to be interested in electricity and lithography. Lithography was a new printing method he wanted to bring to Russia. He showed the Ministry the latest German lithographic printing technology. He was soon sent back to Bavaria. His task was to get lithographic stone from the Solnhofen quarries. In July 1815, he arrived in Munich. He met Alois Senefelder, the inventor of lithography. Senefelder helped Schilling with his task. In December, Schilling visited Bavaria again to pick up the finished stones. During 1815, he met many French and German experts. These included André-Marie Ampère and François Arago.

When he returned to Saint Petersburg, Schilling became head of the Ministry's lithographic print shop. It was set up in spring 1816. Setting up the print shop earned him the Order of Saint Anna. Schilling's shop printed reports, maps, and instructions for the foreign service. It also produced daily summaries of secret information. These were given to the foreign minister, Karl Nesselrode. Then, the minister decided if they went to the tsar. By 1818, Schilling began experimenting with Manchu and Mongolian printing. From 1820, he helped prepare a Chinese-Mongolian-Manchu-Russian-Latin dictionary. His Chinese editions were very high quality for the time.

Schilling managed the print shop until he died. However, this was just one of his side activities. His main job was to develop, distribute, and protect ciphers for Russian embassies. After a service reform in 1823, Schilling became head of the 2nd Secret Branch. He held this position until his death. The secret nature of this work was kept classified for a long time. Friends and colleagues knew he was a mid-level foreign service worker, but nothing more. Schilling was not involved in diplomacy, but he was seen as a diplomat. This was helped by the fact that he often traveled abroad and met foreign officials. His secrecy was rewarded with good payments. For example, in 1830, Nicholas I gave him a bonus of 1000 gold ducats.

His work at the Secret Branch left him plenty of time for other research. This included studying Tibetan scriptures and developing the electrical telegraph. The telegraph became his most famous work. Schilling set up an electrical engineering workshop in the Peter and Paul Fortress. He hired Moritz von Jacobi from Dorpat University to be his assistant. In 1828, Schilling became a State Councillor. He also became a member of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences. In May 1830, he went on a two-year trip to the border between Russia and China. He returned to St. Petersburg in March 1832. He brought a valuable collection of documents in Chinese, Tibetan, Mongolian, and other languages. These were placed in the Imperial Academy of Sciences. Some documents were obtained by showing the small telegraph he carried with him. Back in St. Petersburg, Schilling continued developing his telegraph. There were plans to use it, but Schilling died before they could be finished.

Health Decline and Passing

Schilling's health got worse in the 1830s. He was very overweight. By 1835, he suffered from unknown pains. He asked for permission to travel to Europe for medical help. With help from Nesselrode, he got the tsar's permission. This trip was also a secret mission to gather information. He was to learn about things from telegraphy to charcoal kilns. In September 1835, Schilling attended a conference in Bonn. He showed his telegraph to Georg Wilhelm Muncke. After returning to Saint Petersburg, he did more telegraph experiments. In 1836, he visited Andreas von Ettingshausen's lab in Vienna. He researched new materials for insulation there. In May 1837, Schilling was asked to plan a budget for a telegraph line. This line would connect Peterhof with Kronstadt. He also began early field work. By this time, he had regular pain from a tumor. Doctor Nicholas Arendt, his childhood friend, performed surgery. But it did not help. Schilling died a few months later. He was buried with honors at the Smolenskoye Lutheran Cemetery in Saint Petersburg. All his records, models, and equipment went to Moritz von Jacobi. Jacobi would build the first working telegraph line in Russia in 1841. It connected the Winter Palace with the Army Headquarters.

Schilling's Important Work

Secret Codes (Cryptography)

Schilling's main contribution to secret codes was his bigram cipher. It was adopted for government use in 1823. Schilling's ciphers combined features of substitution ciphers and polyalphabetic ciphers. They used pairs of letters as input. Each pair of letters was converted to a number. This was done using special code tables. The method also involved adding random extra characters to the message. Sometimes, single characters were encoded instead of pairs.

The first three sets of code tables were given to important officials. These included the viceroy of Poland and the foreign minister. Russian diplomats used this method until the 1900s. Individual ciphers were thought to be safe for up to six years. Later, this was reduced to three years. But in reality, some code tables were used for up to twenty years. This went against all security rules.

Journey to the East

In the 1820s, Schilling's academic papers on Eastern languages earned him degrees. He also became a member of British, French, and Russian learned societies. He was a long-time friend of Nikita Bichurin, a leading Russian expert on the East. After Bichurin was disgraced and exiled, Schilling helped him. In 1826, he got Bichurin transferred from prison to a desk job at the Foreign Ministry. Schilling helped Alexander von Humboldt during the early stages of his 1829 expedition to Russia. After Humboldt declined to lead another expedition to the Russian Far East, Schilling was chosen for the role. Preparations began in September 1829. The main staff included Schilling, Bichurin, and Vladimir Solomirsky. The famous poet Alexander Pushkin wanted to join, but Nicholas I ordered him to stay in Russia.

Schilling's main, secret mission was to study how Buddhism was spreading among local tribes. He was to suggest ways to control it. He also had to create rules for Buddhist religious practices. The government did not like independent ideas. It wanted to control Buddhist leaders. The number of Buddhist monks was growing fast. Direct repression was ruled out. This was due to fears of nomads leaving and conflict with China. The government was also worried about a decline in border trade. Schilling was tasked with finding smuggling routes and markets. He also had to estimate the amount of illegal trade. Officially, the mission was only for "studies of population and international trade on the Russo-Chinese frontier." Any other research had to be paid for by Schilling himself. To raise money, Schilling sold his science library.

In May 1830, Schilling began his journey from Saint Petersburg to Kyakhta. This frontier market town became his base for 18 months. His travels from Kyakhta to various Buddhist shrines and border stations covered over 7,690 kilometers. Schilling wrote that his travels were mainly for studying different cultures. According to Bichurin, Schilling spent most of his time with Tibetan and Mongolian lamas. He studied ancient Buddhist scriptures. He was more interested in the languages and history of Far Eastern peoples. His main goal was to find the Kangyur. This was a Tibetan religious text closely guarded by the lamas. Europeans only knew parts of it. At first, Schilling tried to get the complete Kangyur from China. He did not think that poor nomadic Buryats and Mongols could have whole libraries of sacred books. However, he soon found that the Buryats in the Russian Empire owned three copies of the Kangyur. One copy was in Chikoy, less than twenty miles from Kyakhta. Schilling earned the lamas' respect. He was the only Russian who could read Tibetan texts. He easily got permission to read and copy them.

The Chikoy Kangyur could only be copied. But Schilling managed to get parts of a different copy from the chief of the Tsongol tribe. Later, the Khambo Lama of the Buryats sent Schilling a collection of medical and astrological books. Schilling became famous among the Buryats. Some lamas preached that he was a prophet. Others believed he was a reincarnated Khubilgan. His house in Kyakhta became a place for many pilgrimages. This brought more and more manuscripts. Schilling realized that his collection was almost complete. He only needed a few important texts from the Tibetan Buddhist canon. He filled the gaps by hiring over twenty calligraphers. They copied the missing books. Józef Kowalewski, who saw this, wrote that "the Baron" greatly influenced the Buryats. Experts in Tibetan and even Sanskrit languages appeared. Monks began to study their faith more deeply. Many books that were thought to be lost were discovered.

Finally, in March 1831, Schilling obtained the Kangyur and the 224-volume Tengyur. This was at a remote datsan on the Onon River. Local lamas were struggling to print 100 million copies of Om mani padme hum. They had vowed to contribute these to a new shrine. Schilling helped them by promising to print the whole lot. He would print them in tiny lithographed Tibetan script in Saint Petersburg. He kept his promise. He was rewarded with the precious books. This Derge edition of the Kangyur was the first owned by a European. Once the collection was complete, Schilling began cataloging and indexing. His Index of the Narthang Kangyur was printed after his death. It contains 3800 pages in four volumes.

Schilling returned to Moscow in March 1832. One month later, he arrived in Saint Petersburg. He brought reports and plans for cross-border trade and Buddhist clergy. He suggested keeping things as they were. He also suggested keeping an eye on similar issues faced by British administrators in Canton. The government decided not to push the religion issue. A law regulating Buddhists was passed only in 1853. After completing his mission, Schilling focused on telegraphy and secret codes. His work on the Kangyur was finished by an educated Buryat man. This man was brought from Siberia for this specific purpose.

Telegraph Innovations

Schilling first got involved in telegraphy in Munich. He helped Sömmerring with his experiments. Sömmerring used an electrochemical telegraph. This type of telegraph uses electricity to cause a chemical reaction. For example, bubbles form in a glass tube of acid. After returning to St. Petersburg, Schilling did his own experiments with this telegraph. He showed it to Tsar Alexander I in 1812. But Alexander did not want to use it. His successor, Nicholas I (who became tsar in 1825), was careful about new ideas. He was against introducing any mass communication. He agreed to use electrical telegraphy for certain military and civil offices. But he banned public discussion of telegraph technology. This included reports on foreign inventions. Schilling could show his experiments to the public without problems. But he never tried to publish his research. After Schilling's death, Moritz von Jacobi tried to publish a review article. The journal was confiscated and destroyed by the tsar's order. When Schilling learned of Hans Christian Ørsted's discovery in 1820, he changed his focus. Ørsted found that electric current could move compass needles. Schilling decided to work on needle telegraphs. These telegraphs used Ørsted's idea. Schilling used one to six needles in his demonstrations. These needles represented letters or other information.

Early Telegraph Design (1828)

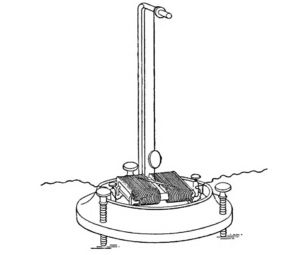

The first Schilling telegraph was finished in 1828. The demonstration set had a double-wire copper line. It had two terminals. Each terminal had a voltaic pile (a type of battery). This provided about 200 mA of current. It also had a Schweigger multiplier for showing signals. There was a switch to send or receive messages. And it had a two-way telegraph key. There were no intermediate repeaters yet. This limited how far the system could send messages. The switches and keys used open containers filled with mercury. The pointer of the multiplier was slowed down by mercury. The coil of each multiplier had 1760 turns of copper wire. The wire was insulated with silk. Two magnetized steel pegs made sure the pointer returned to its off-state. They also helped slow it down.

The code table had 40 characters. It used a variable-length code. This meant one to five bits per character. Unlike the dots and dashes of Morse code, Schilling's bits were encoded by current direction. They were marked as "left" or "right" in the code table. The benefit of variable-length coding was not clear yet. Relying on the operator's memory was too unreliable. So, other researchers convinced Schilling to design a multi-wire system. This system would send bits at the same time. Von Sömmerring used eight bits. Schilling reduced the number of bits to six for a 40-character alphabet.

Schilling took a single-needle instrument with him. He used it for demonstrations on his journey to the Far East. When he returned, Schilling used a binary code on his telegraph. It had multiple needles. He was inspired by the hexagrams from I Ching. He learned about these in the East. These hexagrams are figures used in divination. Each has six stacked lines. Each line can be solid or broken. These are two binary states. This leads to 64 possible figures. The six units of the I Ching fit perfectly with the six needles he needed. These needles coded the Russian alphabet. This was the first time binary coding was used in telecommunications. This was decades before the Baudot code.

Public Demonstration (1832)

On October 21, 1832, Schilling showed his six-needle telegraph. He set it up between two rooms in his apartment building. The rooms were about 100 meters apart. To show a good distance, he rented the entire floor of the building. He ran about 2.4 kilometers of wire around the building. The demonstration was so popular that it stayed open until Christmas. Important visitors included Nicholas I. He had already seen an earlier version in April 1830. Other visitors were Moritz von Jacobi and Alexander von Benckendorff. Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich also visited. The Tsar dictated a ten-word message in French. It was successfully sent over the machine. Alexander von Humboldt saw Schilling's telegraph in Berlin. He then suggested to the Tsar that a telegraph should be built in Russia.

In May 1835, Schilling began a tour of Europe. He demonstrated a one-needle instrument. He did experiments in Vienna with other scientists. They investigated the pros and cons of rooftop and buried cables. The buried cable did not work well. His thin India rubber and varnish insulation was not good enough. In September, he was at a meeting in Bonn. Georg Wilhelm Muncke saw the instrument there. Muncke had a copy made for his lectures. In 1835, Schilling showed a five-needle telegraph to the German Physical Society in Frankfurt. By the time Schilling returned to Russia, his telegraph was well known in Europe. It was often discussed in scientific writings. In September 1836, the British government offered to buy the rights to the telegraph. But Schilling refused. He wanted to use it to develop telegraphy in Russia.

Plans for Installation

In 1836, Nicholas I created a special group. It was to advise on installing Schilling's telegraph. The line would connect Kronstadt, an important naval base, and Peterhof Palace. Prince Alexander Menshikov, the Minister of Marine, led this group. An experimental line was set up in the Admiralty building. It connected Menshikov's office with his subordinates' offices. The five-kilometer line was partly above ground and partly underwater in canals. It had three intermediate Schweigger multipliers. Menshikov submitted a good report. He got the tsar's approval to connect Peterhof with the naval base at Kronstadt. This would be across the Gulf of Finland.

The telegraph Schilling proposed in 1836 was very similar to his 1828 experimental set. It had minor improvements from his Far Eastern trip. It consisted of voltaic piles (batteries), wires, multipliers with repeater switches, and alarm bells. Thin copper wires were insulated with silk-reinforced latex. They were hung from strong hemp cables. Each multiplier had hundreds of turns of silver or copper wire on a brass spool. The pointer's shaft was slowed down by being in mercury. Signal currents were designed to go both ways. Later, Schilling's telegraph was often described as a multi-wire device. It was said to send five or six bits at the same time. However, his 1836 proposal clearly described a double-wire, serial device.

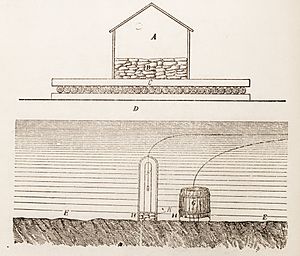

Schilling knew that all ways of insulating underwater cables were worse than bare overhead wires. He wanted to keep the underwater cable as short as possible. He suggested laying a 7.5-kilometer underwater cable from Kronstadt to Oranienbaum. This was the nearest coastal town. Then, an 8-kilometer overhead line would run along the coast to Peterhof. The committee led by Menshikov made fun of this idea. There were many objections. The most important was a security risk. The coastal line would be visible to any boat passing through the Gulf. Menshikov pushed for an alternative route. This was a fully submerged 13-kilometer cable directly to Peterhof.

On May 19, 1837, Menshikov told Schilling that the tsar had approved a fully submerged construction. Schilling started the project. He ordered the submarine cable from a rope factory in St. Petersburg. But he died on August 6, 1837. The project was then canceled.

Single-Wire Code and Recording

Schilling is sometimes said to be the first to create a code for a single-wire telegraph. But there is some doubt about how many needles he used and when. It might be that Schilling used a single-needle setup for demonstrations. This would be for easier transport. Or it might have been a later design inspired by the Gauss and Weber telegraph. In that case, he would not have been the first. The code said to be used with this telegraph can be traced to Alfred Vail. But the variable-length code (like Morse code) shown by Vail is just an example. In any case, two-element signaling alphabets existed before any electrical telegraphy. According to Hubbard, it is more likely that Schilling used the same code as on the six-needle telegraph. But the bits were sent one after another instead of at the same time.

Schilling also looked into automatically recording telegraph signals. But he could not make it work. The device was too complex. His electrical engineering successor, Jacobi, succeeded in doing this in 1841. This was on a telegraph line from the Winter Palace to the General Staff Headquarters.

Mines and Fuses

Another area of Schilling's research was military uses of electricity. This included remote control of land and naval mines. In 1811, Johann Schweigger suggested exploding hydrogen bubbles. These bubbles would be released from a liquid by passing electric current. Schilling discussed this with Sommering. He realized the military potential of the idea. He designed a water-resistant wire. It could be laid in wet ground or through rivers. It had a copper wire insulated with a mix of India-rubber and varnish. Schilling also thought about using telegraphy in the field for military purposes. Sömmerring wrote in his diary, "Schilling is quite childish about his electro-conducting cord."

In September 1812, Schilling showed his first remote-controlled naval fuse to Alexander I. This was on the Neva River in Saint Petersburg. The invention was for coastal defense and sieges. It was not considered suitable for the fast-moving maneuver warfare of the 1812 campaign. The Schilling fuse, patented in 1813, had two pointed carbon electrodes. These produced an electric arc. The electrodes were placed in a sealed box filled with fine gunpowder. The arc ignited the gunpowder.

In 1822, Schilling showed the land version of his fuse to Alexander I. This was at Krasnoye Selo. In 1827, another Schilling mine was shown to Nicholas I. This time, the test was overseen by military engineer Karl Schilder. Schilder was an influential officer and inventor. Schilder pushed the idea through the government. In April 1828, the Inspector General of military engineers approved the development of electrically-fired mines for mass production. Russia had just started a war with the Ottoman Empire. This war often involved sieges of Turkish defenses. The main problem Schilling faced was a lack of batteries suitable for field use. This issue was not solved until after the war.

Right after returning from Siberia, Schilling continued working on mines and fuses. In September 1832, a series of electrically-fired land mines were successfully tested. This time, the technology was ready for use. It was given to the Army. Schilling received the Order of Saint Vladimir, 2nd class. Schilling kept improving land mines until he died. In March 1834, Schilder tested the first naval mine. It used insulated wires invented by Schilling. In 1835, the military performed the first test demolition of a bridge. This was done with an electrically-fired underwater charge. These demolition sets were produced and given to military engineers from 1836. However, the Russian Navy resisted this new technology. They waited until Moritz von Jacobi invented a reliable contact fuse in 1840.

Schilling's Lasting Impact

Schilling regularly wrote to many scientists, writers, and politicians. He was well known in European academic communities. He arranged for historical manuscripts to be published. He also provided Eastern language sorts and matrices to European print shops. However, during his lifetime, he never tried to publish a book in his own name. He also never submitted an article to a journal. The only known publication was the preface to the Index of the Narthang Kangyur. It was printed after his death and without his name. His studies of Eastern languages and Buddhist texts were soon forgotten. The real author of the Index was "rediscovered" in 1847, and then forgotten again. Schilling's research into telegraphy is much better known. Scientists and engineers who wrote about Schilling focused mainly on his telegraph. This shaped his public image as an engineer. Later, various authors wrote about Schilling's Eastern studies and travels. They also wrote about his work with European academics and Russian poets. But no one managed to understand all parts of his personality. Schilling the linguist, Schilling the engineer, and Schilling the socialite seemed like three different people. Moritz von Jacobi was probably the only person at the time who directly linked Schilling's telegraph achievements to his language skills.

The Schilling needle telegraph was never used as it was. But it is partly the ancestor of the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph. This system was widely used in the United Kingdom and the British Empire in the 1800s. Some of its instruments were still used well into the 1900s. Schilling's demonstration in Frankfurt was attended by Georg Wilhelm Muncke. Muncke then had an exact copy of Schilling's device made. Muncke used this for demonstrations in his lectures. One of these lectures was attended by William Fothergill Cooke. Cooke was inspired to build his own version of Schilling's telegraph. However, he did not realize the instrument he saw was Schilling's. He stopped using this method for practical use for a while. He preferred electromagnetic clockwork solutions. He seemed to believe that needle telegraphs always needed many wires. Schilling's method of hanging the needle horizontally by a thread was also not very convenient. This changed when he partnered with Charles Wheatstone. The telegraph they built together was a multiple-needle telegraph. But it had a much stronger mounting based on the galvanometer of Macedonio Melloni. There is no proof that Wheatstone also lectured with a copy of Schilling's telegraph. But he certainly knew about it and lectured on its importance.

Schilling's original telegraph from 1832 is now displayed. It is in the telegraph collection of the A.S. Popov Central Museum of Communications. The instrument was previously shown at the Paris Electrical Exhibition of 1881. His contributions to electrical telegraphy were named an IEEE Milestone in 2009. The Adamini Building at 7 Marsovo Pole, St. Petersburg, has a memorial plaque. Schilling lived there in the 1830s and died there. The plaque was placed in 1886 to mark 100 years since his birth.

|

In Spanish: Pavel Schilling para niños