Baltic Germans facts for kids

| Deutsch-Balten | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| c. 5,200 (Germans currently in Latvia and Estonia, not necessarily Baltic Germans in the same historical and cultural sense) |

|

Historically:

|

|

| Languages | |

| Low German, High German | |

| Religion | |

| Lutheran majority Roman Catholic minority |

|

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Germanic peoples, Germans, Germans in Russia, Estonian Swedes |

The Baltic Germans (called Deutsch-Balten or Deutschbalten in German) were people of German background who lived on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. This area is now known as Estonia and Latvia. For many centuries, they were a very important group in these lands.

From the Middle Ages onwards, German-speaking people were often the main merchants, religious leaders, and landowners. They formed a powerful group that led society, while most local Latvians and Estonians were not nobles. By the 1800s, when Baltic Germans started to feel like a distinct group, many of them were also city dwellers and professionals, not just nobles.

In the 1100s and 1200s, German traders and crusaders began to settle in the eastern Baltic lands. As time went on, the German language became very important for official papers, business, education, and government.

Most of the early German settlers lived in towns in a region called medieval Livonia. However, a small but rich group became the Baltic nobility, owning large farms and estates. After the Great Northern War (1700–1721), when Sweden gave its Livonian lands to the Russian Empire, many German nobles gained high positions in the Russian government and military, especially in Saint Petersburg. Most Baltic Germans were citizens of the Russian Empire until Estonia and Latvia became independent in 1918. After that, they were citizens of Estonia or Latvia until they were forced to move to Nazi Germany in 1939. This happened just before the Soviet Union took over Estonia and Latvia in 1940.

The Baltic German population was never more than 10% of the total people living there. In 1881, about 180,000 Baltic Germans lived in Russia's Baltic areas. By 1914, this number had dropped to 162,000. In 1897, there were about 120,191 Germans in Latvia, making up 6.2% of the population.

The presence of Baltic Germans in the Baltics mostly ended in late 1939. This was after a special agreement called the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and a large-scale movement of people. Nazi Germany moved almost all Baltic Germans to new areas in Poland that Germany had taken over. In 1945, most people of German background were forced to leave these lands by the Soviet army.

Sometimes, Germans from East Prussia and Lithuania are mistakenly called Baltic Germans. However, Germans from East Prussia were citizens of Prussia, and later Germany, because their land was part of the Kingdom of Prussia.

Contents

- Who Were the Baltic Germans?

- How They Came to the Baltics

- Polish-Lithuanian and Swedish Rule

- Russian Rule (1710–1917)

- World War I and Changes

- Independent Baltic States

- Forced Relocation of Baltic Germans (1939–1944)

- Loss of Cultural Heritage (1945–1989)

- Baltic Germans Today

- Famous Baltic Germans

- See also

Who Were the Baltic Germans?

Their Background

Baltic Germans were not a group made up only of people with German roots. Early German knights, traders, and craftspeople often married local women because there were no German women available. Some noble families, like the Lievens, even said they were related to local leaders through these women.

Many German soldiers died during the Livonian War (1558–1583). New German settlers then arrived. Over time, the Low German language spoken by the first settlers was slowly replaced by High German, which the new settlers spoke.

Over their 700-year history, Baltic German families had German roots but also married many Estonians, Livonians, and Latvians. They also married people from other parts of Northern and Central Europe, like Danes, Swedes, and Poles. When this happened, people from other groups often adopted German culture, language, customs, and family names. They then became known as Germans, which helped create the Baltic German identity. For example, the families of Barclay de Tolly and George Armitstead, who came from the British Isles, married into and became part of the Baltic German community.

Where They Lived

Baltic German settlements were found in these areas:

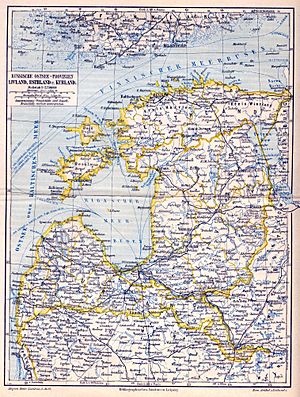

- Estland (present-day northern Estonia); main towns: Reval (Tallinn), Narwa (Narva).

- Livland (present-day southern Estonia and northern/eastern Latvia); main towns: Riga, Dorpat (Tartu), Pernau (Pärnu).

- Kurland (present-day western Latvia); main towns: Mitau (Jelgava), Windau (Ventspils).

- Ösel (the island of Saaremaa in Estonia); main town: Arensburg (Kuressaare).

How They Came to the Baltics

A small number of Germans started to settle in the Baltic region in the late 1100s. This was when traders and Christian missionaries began visiting the coastal lands. These lands were home to tribes who spoke Finnic and Baltic languages.

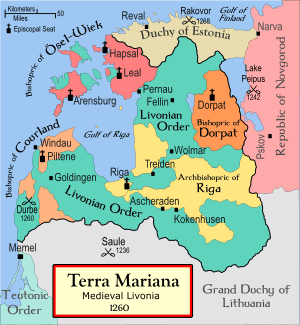

The systematic conquest and settlement of these lands happened during the Northern Crusades in the 12th and 13th centuries. This led to the creation of the Terra Mariana confederation, which was protected by the Pope and the Holy Roman Empire. After a big defeat in the 1236 Battle of Saule, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword joined the Teutonic Knights.

For the next three centuries, German-speaking soldiers, religious leaders, merchants, and craftspeople made up most of the growing city populations. This was because native people were usually not allowed to settle in these towns. Being part of the Hanseatic League and having strong trade links with Russia and Europe made Baltic German traders very rich.

Polish-Lithuanian and Swedish Rule

The military power of the Teutonic Knights became weaker during the wars of the 1400s. The Livonian branch of the Order in the north started to make its own decisions. When the Prussian branch became a Polish vassal state in 1525, the Livonian branch stayed independent. Livonia became mostly Protestant during the Protestant Reformation.

In 1558, the Tsardom of Russia started the Livonian War. This war lasted 20 years and involved Poland, Sweden, and Denmark. In 1561, Terra Mariana ended. Its lands were divided among Denmark, Sweden, and Poland. Poland created the Duchy of Livonia and gave the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia to the last Master of the Livonian Order, Gotthard Kettler. The land was then divided among the remaining knights, who became the basis of the Baltic nobility.

The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia was a German-speaking country until 1795. Sweden took control of the northern part of Livonia, ruling parts of Estonia from 1561 to 1710 and Swedish Livonia from 1621 to 1710. Sweden agreed with the local Baltic German nobles not to take away their political rights.

The Academia Gustaviana (now University of Tartu) was founded in 1632 by King Gustavus II Adolphus of Sweden. It was the only university in the former Livonian lands and became a very important place for Baltic German thinkers.

By the end of the 1600s, Sweden took back some land from German nobles in its Baltic provinces. This made serfs (unfree peasants) into free peasants. However, when Russia took over these lands in 1710, it gave the German landowners their rights back.

Russian Rule (1710–1917)

Between 1710 and 1795, after Russia won the Great Northern War and divided Poland three times, the areas where Baltic Germans lived became part of the Russian Empire. These were called the Baltic governorates: Courland Governorate, Governorate of Livonia, and Governorate of Estonia.

Self-Rule and Influence

The Baltic provinces kept a lot of self-rule. Local government was run by the Baltic nobility in each province. Cities were led by German mayors.

From 1710 until about 1880, the Baltic German leaders had a lot of freedom from the Russian government. They also gained great political influence in the Russian royal court. Many Baltic German nobles also took important jobs in the Russian imperial government.

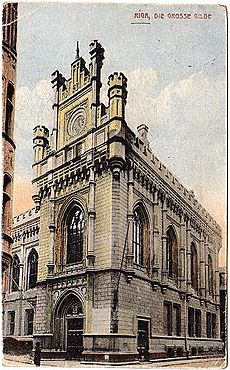

Germans, other than the large estate owners, mainly lived in cities like Riga, Reval, and Dorpat. Even in the mid-1800s, many of these cities still had a German majority. By 1867, 42.9% of Riga's population was German. Until the late 1800s, most of the educated and professional people in the region were Germans.

German political and cultural self-rule ended in the 1880s. This was when Russification began, replacing German administration and schooling with the Russian language. After 1885, provincial governors were usually Russians.

Rise of Local Peoples

Years of peace under Russian rule brought more wealth. Many new manor houses were built on country estates. However, the economic system made life harder for the native population.

Local Latvian and Estonian people had fewer rights under the Baltic German nobles. This was compared to farmers in Germany, Sweden, or Poland. Unlike the Baltic Germans, Estonians and Latvians had limited rights. They mostly lived in rural areas as serfs (unfree workers), tradesmen, or servants. They had no right to leave their masters and no last names. This was common in the Russian Empire until the 1800s. Then, the end of serfdom gave these people more freedom and some political rights.

In 1804, a new law was introduced to improve conditions for serfs. Serfdom was ended in all Baltic provinces between 1816 and 1820. This was about 50 years earlier than in Russia itself. For some time, there was no major conflict between German speakers and local residents.

Before, any Latvian or Estonian who became successful was expected to become German and forget their roots. But by the mid-1800s, German city dwellers felt more competition from native people. After the First Latvian National Awakening and Estonian national awakening, Latvians and Estonians formed their own middle class. They moved to German-dominated towns and cities in growing numbers.

The Revolution of 1905 led to attacks against Baltic German landowners. Manor houses were burned, and some nobles were harmed. During this revolution, rebels burned over 400 manor houses and German-owned buildings. In response, Russian soldiers, helped by German nobles, burned farms and arrested thousands.

World War I and Changes

World War I ended the close ties between Baltic Germans and the Russian government. Because of their German background, they were seen as enemies by Russians. They were also seen as traitors by the German Empire if they stayed loyal to Russia. Their loyalty was questioned, and rumors of German spies grew. All German schools and groups were closed in Estonia. Germans were told to leave Courland for inner Russia.

Courland was taken by Germany in 1915. After Russia surrendered in 1918, Germany occupied the rest of the Baltic provinces.

United Baltic Duchy Idea

In early 1918, Livonian and Estonian nobles told Soviet leaders they wanted to break away from Russia. In response, the Bolsheviks, who controlled Estonia, arrested many leading Germans and sent them to Russia. After a peace treaty, they were allowed to return. Germany gained control over Courland, Riga, Livonia, and Estonia.

In the spring of 1918, Baltic Germans announced the return of the independent Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. They wanted to join it with the Kingdom of Prussia. On April 12, 1918, Baltic German leaders from all Baltic provinces met in Riga. They asked the German Emperor to take over the Baltic lands.

Later, a plan for a United Baltic Duchy was made, to be ruled by a German duke. This was instead of Germany taking over directly. Its ruling council met in November 1918, but the plan ended when the German Empire collapsed.

Independent Baltic States

The power and special rights of Baltic Germans ended when the Russian Empire fell apart after the 1917 revolution. Estonia and Latvia became independent in 1918–1919.

Baltic Germans faced difficulties under the Bolshevik governments in Estonia and Latvia. These governments were short-lived but targeted Germans, sometimes harming them just because of their nationality.

After the German Empire collapsed, Baltic Germans in Estonia started forming volunteer groups to defend against the Bolshevik threat. The Estonian government approved this in November 1918, and the Volunteer Baltic Battalion was formed.

During the Estonian and Latvian independence wars (1918–1920), many Baltic Germans joined the new Estonian and Latvian armies. They helped secure the independence of these countries from Russia. These German military units were known as the Baltische Landeswehr in Latvia and Baltenregiment in Estonia.

Baltische Landeswehr units took Riga in May 1919. This was followed by a period where many people, mostly Latvians, were harmed as suspected Bolshevik supporters.

Baltic German estates were often targets of local Bolsheviks. After independence, land was taken over by the state, and Baltic Germans lost their positions of power. Baltic Germans in the Livonian area found themselves in two new countries. Both countries introduced major land reforms that affected the large landowners, who were mostly Germans.

After the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Russian Civil War, many Baltic Germans moved to Germany. After 1919, many felt they had to leave the newly independent states for Germany, but many stayed as regular citizens.

In 1925, there were 70,964 Germans in Latvia (3.6% of the population). By 1935, this was 62,144 (3.2%). Riga remained the largest German center, with 38,523 Germans in 1935.

Even though the German landowning class lost most of their lands, they continued to work in their jobs and run their companies. German cultural self-rule was respected. German political parties in Latvia and Estonia took part in elections and won seats.

At the same time, as the new states built their own systems, this often reduced the status of their minority groups. In Latvia, children of mixed marriages were registered as Latvians. In Estonia, they took the nationality of their fathers, who were increasingly Estonians. This quickly lowered the number of German children. German place names were removed from public use. German churches were given to local congregations.

Land Reforms

When Estonia and Latvia became independent, Baltic Germans owned 58% of the land in Estonia and 48% in Latvia. Major land reforms were put in place in both countries. The goal was to reduce German power and give land to veterans of the independence wars and landless peasants. This greatly hurt the German noble families and their economic base.

In October 1919, the Estonian parliament took over 1,065 estates (96.6% of all estates). A 1926 law set compensation for former owners at about 3% of the land's market value. There was no compensation for forests. This quickly made the German noble class lose their wealth, even if they could keep about 50 hectares of their land.

In September 1920, the Latvian assembly took over 1,300 estates with 3.7 million hectares of land. Former German owners could keep 50 hectares of land and farm equipment. In 1924, the Latvian parliament decided that no compensation would be paid to former owners.

Life in Independent Estonia

In Estonia, there was only one German party. Germans never received government minister jobs. The three largest minority groups – Germans, Swedes, and Russians – sometimes formed election groups. The German-Baltic Party in Estonia was created to protect the interests of German landowners. They wanted money for their nationalized lands. They received no compensation but could keep small plots of land.

Germans were not allowed to hold government or military jobs. Many Germans sold their properties and moved to Scandinavia or Western Europe. Most of the grand manor houses were taken over by schools, hospitals, local governments, and museums.

Estonia had a smaller Baltic German population than Latvia. As Estonians filled professional jobs like law and medicine, there was less of a leadership role for Baltic Germans.

In February 1925, Estonia passed a law for cultural self-rule for national minorities, including Germans. Despite this, the German community in Estonia continued to shrink as most young people chose to move away. By 1934, there were 16,346 Baltic Germans in Estonia, making up 1.5% of the population.

Estonia allowed German-language schools. In 1928, 3,456 students attended German schools.

Life in Independent Latvia

In Latvia, Baltic Germans remained an active and organized group. They lost some influence after a government change in 1934. A few times, Germans held minister jobs in coalition governments.

Six, and later seven, German parties existed and formed a group in the Latvian parliament. Leading politicians included Baron Wilhelm Friedrich Karl von Fircks and Paul Schiemann.

Minority cultural matters were overseen by the Ministry of Culture. In 1923, there were 12,168 students in German schools. The Herder Institute, a private German university, was also established.

In 1926, the German community started a voluntary self-tax. They asked all Germans to give up to 3% of their monthly income to community activities. In 1928, the Baltic German National Community was created as the main group representing Baltic Germans in Latvia.

The self-rule of German schools was greatly limited between 1931 and 1933. This was when the Minister of Education introduced a policy to make minority schools more Latvian. In July 1934, German schools came under the full control of the Ministry of Education.

After a government takeover in May 1934, all independent groups and businesses had to close. This hit the German community especially hard. They lost their old community centers, and all their property was taken over by the state. Then, many Jewish, Russian, and German businesses were bought by state-owned banks. This was done to reduce minority control over businesses.

Forced Relocation of Baltic Germans (1939–1944)

-

Nazi plans to "resettle" Baltic Germans in "Warthegau"

1939–1940 Relocation

In 1940, Estonia and Latvia became Soviet republics. A key condition from Hitler to Stalin in August 1939 was that all Germans living in Estonia and Latvia had to move to areas controlled by Germany. This was part of the Nazi–Soviet population transfers. Stalin then set up Soviet military bases in Estonia and Latvia in late 1939.

In a speech in October 1939, Hitler announced that German minorities should be moved back to Germany. This move was managed by Heinrich Himmler.

Agreements were signed with Estonia and Latvia in 1939 and 1940. These agreements covered the move of Baltic Germans and the closing of their schools, cultural groups, and churches. Nazi Germany successfully made the Baltic Germans leave their homes quickly. Because of wartime rules, Germans were not allowed to take valuables, historical items, fuel, or even food. Many household items and small businesses were sold off quickly. Larger properties and businesses were sold over a longer time by a special German group.

- About 13,700 Baltic Germans moved from Estonia by early 1940.

- Around 51,000 Baltic Germans moved from Latvia by early 1940.

The Estonian and Latvian governments published lists of the names of adult Baltic Germans who moved. These lists included their birthdate, birthplace, and last address in the Baltics.

Baltic Germans left by ships from Estonian and Latvian ports. They sailed to ports in Poland, which was then controlled by Germany. From there, they were taken to cities like Poznań and Łódź in a region called Reichsgau Wartheland. The "new" homes and farms they received had been owned by Poles and Jews just a few months earlier. These people had been forced out or harmed when Nazi Germany invaded Poland. The new arrivals helped Nazi plans to make these lands more German.

Spring 1941 Relocation

In early 1941, the Nazi German government arranged another move for those who had not left in 1939 or 1940. This was called the Nachumsiedlung. This time, no money was offered for any property left behind. This group of people was seen with great suspicion or as traitors because they had not left in 1939. Most of these new arrivals were first put in special camps. Unknown to the public, the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union was only a few months away. This was Hitler's last chance to move these people during peacetime.

By this time, the remaining Baltic Germans in Estonia and Latvia were in a very different situation. Their countries were now controlled by the Soviet Union. People who had been wealthy or held important positions before 1939 faced strong pressure and threats. Many arrests and some killings had happened. Fearing things would get worse, most of the remaining Baltic Germans decided to leave. About 7,000 moved from Estonia by late March 1941, and about 10,500 moved from Latvia by late March 1941.

No books were published listing those who moved in 1941. However, the archives in Estonia and Latvia still have the lists of everyone who left that year.

1941–1944 Period

A very small number of Baltic Germans refused to move again and stayed in the Baltics after March 1941. Some were sent to Siberian labor camps by the Soviet authorities starting in June 1941.

After the Nazi attack on the Soviet Union and the capture of Latvia and Estonia, a small number of Baltic Germans were allowed to return. They worked as translators. However, many who had moved wanted to return to their homelands, but this was not allowed by the Nazi SS. Many German Baltic men were forced to join the German army.

The Germans who had been moved fled west with the retreating German army in 1944. There are no exact numbers or lists for them. However, several thousand Baltic Germans remained in the Baltics after 1944. They faced widespread unfair treatment by the Soviet authorities. As a result, many hid their Baltic German background. Most of those who stayed after 1944 were children of mixed marriages or were married to Estonians, Latvians, or Russians. Their descendants no longer see themselves as German.

"Second Relocation" in 1945

When the Soviet Union advanced into Poland and Germany in late 1944 and early 1945, Baltic Germans were moved by German authorities (or simply fled) from their "new homes." They went to areas further west to escape the advancing Soviet army. Most settled in West Germany, with some ending up in East Germany.

Unlike the moves in 1939–1941, this time the evacuation was often delayed until the last moment. It was too late to do it in an organized way. Almost everyone had to leave most of their belongings behind. Since they had only lived in these "new" homes for about five years, this felt like a second forced move for them, though under different circumstances.

Many Baltic Germans were on board the ship Wilhelm Gustloff when it was sunk by a Soviet submarine in January 1945. It is estimated that about 9,400 people died, making it one of the largest losses of life in a single ship sinking in history. Many Baltic Germans also died when the SS General von Steuben sank in February 1945.

Two books list the names and information of all Baltic Germans who died because of the relocations and wartime conditions between 1939 and 1947.

After Estonia and Latvia came under Soviet rule after 1944, most Baltic Germans did not return to the Soviet-controlled Baltics.

Canada

Many thousands of Baltic Germans moved to Canada starting in 1948. This was supported by the Canadian Governor General, The Earl Alexander of Tunis. He had known many Baltic Germans when he led the Baltische Landeswehr for a short time in 1919. At first, only 12 Germans were allowed to settle in 1948. Because this group behaved well, many thousands of Baltic Germans were soon allowed to move to Canada in the following years.

A small group of Latvians and Baltic Germans moved to Newfoundland. They were part of a program to start new industries. Several families in Corner Brook built and worked in cement and gypsum plants. These plants provided important materials for building Newfoundland's infrastructure after it joined Canada.

Loss of Cultural Heritage (1945–1989)

During the Soviet era, the Soviet authorities in Estonia and Latvia wanted to erase any signs of German rule from past centuries. Many statues, monuments, buildings, or landmarks with German writing were destroyed, damaged, or left to fall apart.

The largest Baltic German cemeteries in Estonia, Kopli cemetery and Mõigu cemetery, were completely destroyed by the Soviet authorities. The Great Cemetery of Riga, the largest burial ground for Baltic Germans in Latvia, also had most of its graves destroyed by the Soviets.

Baltic Germans Today

The current governments of Estonia and Latvia, which became independent again in 1991, generally have a positive view of the contributions of Baltic Germans. They see how Baltic Germans helped develop their cities and countries throughout history. Sometimes, there is some criticism related to the large landowners who controlled most of the rural areas and the local Estonians and Latvians until 1918.

After Estonia became independent from the Soviet Union in 1991, the group of German Baltic nobility living in exile sent a message to the future president. They stated that no member of their group would claim ownership of their former lands in Estonia. This, and the fact that the first German ambassadors to Estonia and Latvia were both Baltic Germans, helped improve relations between Baltic Germans and these two countries.

Working together, Baltic German groups and the governments of Estonia and Latvia have been able to restore many small Baltic German plaques and landmarks. This includes monuments to those who fought in the 1918–1920 War of Independence.

Since 1989, many older Baltic Germans, or their children and grandchildren, have visited Estonia and Latvia. They look for traces of their past, their family homes, and their family histories. Most of the remaining manor houses have new owners and operate as hotels that are open to the public.

Famous Baltic Germans

Baltic Germans played important roles in the societies of what are now Estonia and Latvia for most of the time from the 1200s to the mid-1900s. Many became famous scientists, like Karl Ernst von Baer and Emil Lenz. Others were explorers, such as Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen and Adam Johann von Krusenstern. A number of Baltic Germans served as high-ranking generals in the Russian Imperial Army and Navy, including Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly and Paul von Rennenkampf.

Many Baltic Germans, like Baron Pyotr Wrangel and Prince Anatol von Lieven, joined the Whites and other groups fighting against the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War.

See also

In Spanish: Alemanes del Báltico para niños

In Spanish: Alemanes del Báltico para niños

- Baltic nobility

- Cemeteries

- Kopli cemetery

- Mõigu cemetery

- Great Cemetery

- Raadi cemetery

- Courland

- Deutsch-Baltische Gesellschaft

- Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–50)

- Freikorps in the Baltic

- History of Germans in Russia and the Soviet Union

- Livonia

- Livonian Confederation

- Nazi-Soviet population transfers

- Northern Crusades

- Revalsche Zeitung

- Teutonic Knights

- Estonian Swedes

- List of Russian explorers

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |