Tibetan script facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tibetan |

|

|---|---|

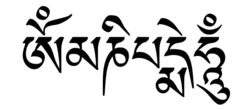

The mantra "Om mani padme hum"

|

|

| Type | Abugida |

| Spoken languages | |

| Time period | c. 620–present |

| Parent systems | |

| Child systems |

|

| Sister systems | Meitei, Sharada, Siddham, Kalinga, Bhaiksuki |

| Unicode range | U+0F00–U+0FFF Final Accepted Script Proposal of the First Usable Edition (3.0) |

| ISO 15924 | Tibt |

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | |

The Tibetan script is a special writing system. It is called an abugida. This means each letter usually has a vowel sound built into it. The script comes from older Indian writing systems. It is used to write several Tibetic languages. These include Tibetan, Dzongkha, Sikkimese, Ladakhi, Jirel, and Balti.

The Tibetan script was created around the year 620. A Tibetan minister named Thonmi Sambhota developed it. He made it for King Songsten Gampo. The script is also used for some other languages. These are languages that have close ties to Tibet. Examples include Thakali and Nepali.

There are two main forms of the script. The printed form is called uchen script. The handwritten, flowing style is called umê script. You can find this writing system all across the Himalayas and Tibet. It is a big part of the Tibetan identity. This identity spreads across areas in India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Tibet. The Tibetan script also led to other scripts. These include Lepcha and ʼPhags-pa script.

Contents

How the Tibetan Script Began

According to Tibetan history, the Tibetan script was created during the time of King Songsten Gampo. His minister, Thonmi Sambhota, was key to this. The king sent Thonmi Sambhota to India. He went with 16 other students. Their goal was to study Buddhism, Sanskrit, and different written languages. They developed the Tibetan script from an older script called the Gupta script. This happened at the Pabonka Hermitage.

This creation took place around 620 AD. It was at the start of King Songsten Gampo's rule. The king had 21 important Sutra texts. These texts were later translated into Tibetan. In the early 7th century, the Tibetan script was used for many things. It helped write down holy Buddhist texts. It was also used for civil laws and a Tibetan Constitution.

Some modern experts have different ideas. They suggest the script might have developed later. New research also hints that other Tibetan scripts existed before this one. But the earliest known writings in the current Tibetan script are from 650 AD. This supports the idea that the script was developed around 620 AD.

Over time, the way Tibetan was written was standardized. The most important change happened in the early 9th century. This official spelling system helped translate Buddhist scriptures. This standard spelling has not changed much since then. However, the spoken language has changed a lot. For example, some complex consonant sounds are no longer pronounced. This means there is a big difference today. The way words are spelled often reflects 9th-century Tibetan. But the way they are pronounced is very different.

Some people think the spelling should be updated. They want to write Tibetan as it is spoken today. For example, writing Kagyu instead of Bka'-rgyud. But many Buddhist followers believe the old spelling should stay. This makes it hard for some modern Tibetan languages to create their own written forms.

Understanding the Tibetan Script

The Basic Alphabet

In the Tibetan script, words are written from left to right. A small mark called a tsek (་) separates syllables. Since many Tibetan words have only one syllable, this mark often acts like a space. Regular spaces are not used between words.

The Tibetan alphabet has thirty basic letters. These are sometimes called "radicals." They represent consonant sounds. Like other scripts from India, each consonant letter has a built-in vowel sound. This sound is usually /a/. The letter ཨ is also used for other vowel marks.

Some Tibetan dialects have tones, like Chinese. But the language did not have tones when the script was invented. So, there are no special symbols for tones. However, tones developed from other sound features. This means you can often guess the tone from the old spelling of a word.

| Unaspirated high |

Aspirated medium |

Voiced low |

Nasal low |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Letter | IPA | Letter | IPA | Letter | IPA | Letter | IPA | |

| Guttural | ཀ | /ka/ | ཁ | /kʰa/ | ག | /ɡa/ | ང | /ŋa/ |

| Palatal | ཅ | /tʃa/ | ཆ | /tʃʰa/ | ཇ | /dʒa/ | ཉ | /ɲa/ |

| Dental | ཏ | /ta/ | ཐ | /tʰa/ | ད | /da/ | ན | /na/ |

| Labial | པ | /pa/ | ཕ | /pʰa/ | བ | /ba/ | མ | /ma/ |

| Dental | ཙ | /tsa/ | ཚ | /tsʰa/ | ཛ | /dza/ | ཝ | /wa/ |

| low | ཞ | /ʒa/ | ཟ | /za/ | འ | /ɦa/ ⟨ʼa⟩ | ཡ | /ja/ |

| medium | ར | /ra/ | ལ | /la/ | ཤ | /ʃa/ | ས | /sa/ |

| high | ཧ | /ha/ | ཨ | /a/ ⟨ꞏa⟩ | ||||

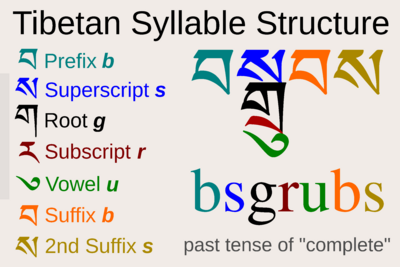

How Consonants Join Together

One cool thing about the Tibetan script is how consonants can join. They can be written as main letters or in special forms. These forms are called subscript and superscript. They help create consonant clusters.

Let's look at an example. The letter ཀ makes the /ka/ sound. When it becomes ཀྲ, it sounds like /kra/. When it's རྐ, it sounds like /ka/. In both cases, ཀ is the main letter. But the letter ར changes its position. If ར comes in the middle (like in /kra/), it's added below as a subscript. If ར comes before the main consonant (like in /rka/), it's added above as a superscript. The letter ར even changes its shape when it's above most other consonants.

Besides superscripts and subscripts, some consonants can be placed in other spots. They can be before the main letter (prescript). Or they can be after it (postscript). Some can even be after the postscript (post-postscript). For example, ག, ད, བ, མ, and འ can be prescripts. Many consonants can be postscripts. Only ད and ས can be post-postscripts.

Letters Above (Head Letters)

The "head" letter, or superscript, goes above the main consonant. Only ར, ལ, and ས can be head letters.

- When ར, ལ, or ས are above ཀ, ཅ, ཏ, པ, and ཙ, their sounds don't change in Lhasa Tibetan. For example:

* རྐ /ka/, རྟ /ta/ * ལྐ /ka/, ལྕ /t͡ʃa/ * སྐ /ka/, སྟ /ta/

- When ར, ལ, or ས are above ག, ཇ, ད, བ, and ཛ, they change. They lose their breathy sound and become voiced in Lhasa Tibetan. For example:

* རྒ /ga/, རྗ /d͡ʒa/ * ལྒ /ga/, ལྗ /d͡ʒa/ * སྒ /ga/, སྡ /da/

- When ར, ལ, or ས are above nasal consonants like ང, ཉ, ན, and མ, they get a high tone in Lhasa Tibetan. For example:

* རྔ /ŋa/, རྙ /ɲa/ * ལྔ /ŋa/ * སྔ /ŋa/, སྙ /ɲa/

- When ལ is above ཧ, it makes a special sound. It becomes a voiceless alveolar lateral approximant in Lhasa Tibetan:

* ལྷ /l̥a/

Letters Below (Sub-joined Letters)

Only ཡ, ར, ལ, and ཝ can be placed below a main consonant. When they are in this position, they are called btags, meaning "hung on" or "attached." For example, བ་ཡ་བཏགས་བྱ (pronounced /pʰa.ja.taʔ.t͡ʃʰa/). The letter ཝ is an exception. It is just read as it is and does not change the sound of the consonant it is joined to. For example, ཀ་ཝ་ཟུར་ཀྭ (pronounced /ka.wa.suː.ka/).

Vowel Marks

The main vowel sounds in Tibetan are /a/, /i/, /u/, /e/, and /o/. The /a/ sound is already part of each consonant. The other vowels are shown with special marks. So, ཀ is /ka/. Then ཀི is /ki/, ཀུ is /ku/, ཀེ is /ke/, and ཀོ is /ko/.

The vowel marks for /i/, /e/, and /o/ are placed above the consonants. The mark for /u/ is placed below. In old Tibetan, there was a reversed /i/ mark, but its meaning is not clear. In written Tibetan, there is no difference between long and short vowels. This is only seen in words borrowed from other languages, especially Sanskrit.

| Vowel mark | IPA | Vowel mark | IPA | Vowel mark | IPA | Vowel mark | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ི | /i/ | ུ | /u/ | ེ | /e/ | ོ | /o/ |

Numbers in Tibetan

Tibetan has its own set of numbers. They look different from the numbers we use every day.

| Tibetan numerals | ༠ | ༡ | ༢ | ༣ | ༤ | ༥ | ༦ | ༧ | ༨ | ༩ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Devanagari numerals | ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ |

| Arabic numerals | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Tibetan fractions | ༳ | ༪ | ༫ | ༬ | ༭ | ༮ | ༯ | ༰ | ༱ | ༲ |

| Arabic fractions | -0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 6.5 | 7.5 | 8.5 |

Punctuation Marks

Tibetan script uses various punctuation marks. They help organize text and show meaning.

| Symbol/ Graphemes |

Name | Function |

|---|---|---|

| ༄༅། ། | ཡིག་མགོ yig mgo |

Marks the beginning of a text, often on a front page. |

| ༃ | གཏེར་ཡིག་མགོ gter yig mgo |

Used for special religious texts called terma. |

| ༁ | ཡིག་མགོ་ཨ་ཕྱེད yig mgo a phyed |

Another mark used for terma texts. |

| ༆ | དཔེ་རྙིང་ཡིག་མགོ dpe rnying yig mgo |

A different yig mgo found in very old Tibetan texts. |

| ༉ | བསྐུར་ཡིག་མགོ bskur yig mgo |

Used for lists in Dzongkha. |

| ་ | ཚེག tseg |

Separates syllables; also helps align text. |

| ། | ཤད shad |

Like a full stop, comma, or semicolon. Marks the end of a sentence or part of a sentence. |

| ། ། | ཉིས་ཤད nyis shad |

Marks the end of a paragraph or a topic. |

| ༎ །། | བཞི་ཤད bzhi shad |

Marks the end of a chapter or a whole section. |

| ། །། | གསུམ་ཤད gsum shad |

Same as bzhi shad, but used when the letter before it is ཀ or ག. |

| ༑ | རིན་ཆེན་སྤུངས་ཤད rin chen spungs shad |

Replaces shad after single syllables. It shows that the word continues from the line above. |

| ༏ | ཚེག་ཤད tsheg shad |

A different version of rin chen spungs shad. |

| ༐ | ཉིསཚེག་ཤད nyis tsheg shad |

Another version of rin chen spungs shad. |

| ༈ | སྦྲུལ་ཤད sbrul shad |

Marks the start of a new text. It also separates chapters and surrounds added text. |

| ༔ | གཏེར་ཤད gter shad |

Replaces shad in terma texts. |

| ༒ | རྒྱ་གྲམ་ཤད rgya gram shad |

Sometimes used instead of yig mgo in terma texts. |

| ༸ | ཆེ་མགོ che mgo |

Means "big head." Used before names of important lamas, like the Dalai Lama, to show great respect. |

| ༴ | བསྡུས་རྟགས bsdus rtags |

Shows that something is repeated. |

| ༓ | འཛུད་རྟགས་མེ་ལོང་ཅན 'dzud rtags me long can |

A caret. It shows where text needs to be added. |

| ༼ | ཨང་ཁང་གཡོན་འཁོར ang khang g.yon 'khor |

Left roof bracket. |

| ༽ | ཨང་ཁང་གཡས་འཁོར ang khang g.yas 'khor |

Right roof bracket. |

| ༺ | གུག་རྟགས་གཡོན gug rtags g.yon |

Left bracket. |

| ༻ | གུག་རྟགས་གཡས gug rtags g.yas |

Right bracket. |

Using Tibetan Script for Other Languages

The Tibetan alphabet can also be used to write other languages. These include Balti, Chinese, and Sanskrit. When used for these languages, the Tibetan alphabet often gets extra or changed letters. These help represent sounds not found in Tibetan.

Extra Letters for Other Languages

| Letter | Used in | Romanization & IPA |

|---|---|---|

| ཫ | Balti | qa /qa/ (/q/) |

| ཬ | Balti | ɽa /ɽa/ (/ɽ/) |

| ཁ༹ | Balti | xa /χa/ (/χ/) |

| ག༹ | Balti | ɣa /ʁa/ (/ʁ/) |

| ཕ༹ | Chinese | fa /fa/ (/f/) |

| བ༹ | Chinese | va /va/ (/v/) |

| གྷ | Sanskrit | gha /ɡʱ/ |

| ཛྷ | Sanskrit | jha /ɟʱ, d͡ʒʱ/ |

| ཊ | Sanskrit | ṭa /ʈ/ |

| ཋ | Sanskrit | ṭha /ʈʰ/ |

| ཌ | Sanskrit | ḍa /ɖ/ |

| ཌྷ | Sanskrit | ḍha /ɖʱ/ |

| ཎ | Sanskrit | ṇa /ɳ/ |

| དྷ | Sanskrit | dha /d̪ʱ/ |

| བྷ | Sanskrit | bha /bʱ/ |

| ཥ | Sanskrit | ṣa /ʂ/ |

| ཀྵ | Sanskrit | kṣa /kʂ/ |

- In Balti, the letters ཀ ར (ka, ra) are reversed to make ཫ ཬ (qa, ɽa).

- For Sanskrit, some letters like ṭa, ṭha, ḍa, ṇa, ṣa are made by reversing Tibetan letters. For example, ཏ (ta) becomes ཊ (ṭa).

- Traditionally, Sanskrit sounds like ca, cha, ja, jha are written as ཙ ཚ ཛ ཛྷ in Tibetan. Today, ཅ ཆ ཇ ཇྷ can also be used.

Extra Vowel Marks and Changes

| Vowel Mark | Used in | Romanization & IPA |

|---|---|---|

| ཱ | Sanskrit | ā /aː/ |

| ཱི | Sanskrit | ī /iː/ |

| ཱུ | Sanskrit | ū /uː/ |

| ཻ | Sanskrit | ai /ɐi̯/ |

| ཽ | Sanskrit | au /ɐu̯/ |

| ྲྀ | Sanskrit | ṛ /r̩/ |

| ཷ | Sanskrit | ṝ /r̩ː/ |

| ླྀ | Sanskrit | ḷ /l̩/ |

| ཹ | Sanskrit | ḹ /l̩ː/ |

| ཾ | Sanskrit | aṃ /◌̃/ |

| ྃ | Sanskrit | aṃ /◌̃/ |

| ཿ | Sanskrit | aḥ /h/ |

| Symbol/ Graphemes |

Name | Used in | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| ྄ | srog med | Sanskrit | Stops the built-in vowel sound. |

| ྅ | paluta | Sanskrit | Used to make vowel sounds longer. |

Consonant Combinations

When writing other languages, the rules for combining consonants change. Any letter can be a superscript or subscript. This means there's no need for prescript or postscript positions.

Typing Tibetan Script on Computers

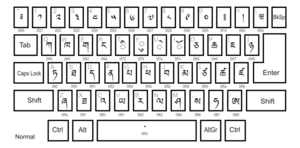

Tibetan Keyboard Layout

Computers can now support the Tibetan keyboard. Microsoft Windows Vista was the first version to include it. Linux has had this layout since 2007. On Ubuntu, you can add Tibetan language support easily. The keyboard layout is similar to Microsoft Windows.

Apple's Mac OS X also supports Tibetan. Versions 10.5 and newer have it. There are three different keyboard layouts available: Tibetan-Wylie, Tibetan QWERTY, and Tibetan-Otani.

Dzongkha Keyboard Layout

The Dzongkha keyboard layout helps type Dzongkha text on computers. The government of Bhutan created this standard layout in 2000. It was updated in 2009 to include new characters. The keys are arranged in the same order as the Dzongkha and Tibetan alphabet. This makes it easy to learn for anyone who knows the alphabet. You use the Shift key to type subjoined (combining) consonants.

The Dzongkha keyboard layout is available on Microsoft Windows, Android, and most Linux systems.

Tibetan in Unicode

Tibetan was one of the first scripts in the Unicode Standard in 1991. Unicode is a system that gives a unique number to every character in every language. This allows computers to display text correctly. Tibetan was removed in 1993 but added back in 1996.

The special Unicode section for Tibetan is U+0F00 to U+0FFF. It includes all the letters, numbers, and punctuation marks. It also has special symbols used in religious texts.

| Tibetan[1][2][3] Official Unicode Consortium code chart: https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0F00.pdf (PDF) |

||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+0F0x | ༀ | ༁ | ༂ | ༃ | ༄ | ༅ | ༆ | ༇ | ༈ | ༉ | ༊ | ་ | ༌ NB |

། | ༎ | ༏ |

| U+0F1x | ༐ | ༑ | ༒ | ༓ | ༔ | ༕ | ༖ | ༗ | ༘ | ༙ | ༚ | ༛ | ༜ | ༝ | ༞ | ༟ |

| U+0F2x | ༠ | ༡ | ༢ | ༣ | ༤ | ༥ | ༦ | ༧ | ༨ | ༩ | ༪ | ༫ | ༬ | ༭ | ༮ | ༯ |

| U+0F3x | ༰ | ༱ | ༲ | ༳ | ༴ | ༵ | ༶ | ༷ | ༸ | ༹ | ༺ | ༻ | ༼ | ༽ | ༾ | ༿ |

| U+0F4x | ཀ | ཁ | ག | གྷ | ང | ཅ | ཆ | ཇ | ཉ | ཊ | ཋ | ཌ | ཌྷ | ཎ | ཏ | |

| U+0F5x | ཐ | ད | དྷ | ན | པ | ཕ | བ | བྷ | མ | ཙ | ཚ | ཛ | ཛྷ | ཝ | ཞ | ཟ |

| U+0F6x | འ | ཡ | ར | ལ | ཤ | ཥ | ས | ཧ | ཨ | ཀྵ | ཪ | ཫ | ཬ | |||

| U+0F7x | ཱ | ི | ཱི | ུ | ཱུ | ྲྀ | ཷ | ླྀ | ཹ | ེ | ཻ | ོ | ཽ | ཾ | ཿ | |

| U+0F8x | ྀ | ཱྀ | ྂ | ྃ | ྄ | ྅ | ྆ | ྇ | ྈ | ྉ | ྊ | ྋ | ྌ | ྍ | ྎ | ྏ |

| U+0F9x | ྐ | ྑ | ྒ | ྒྷ | ྔ | ྕ | ྖ | ྗ | ྙ | ྚ | ྛ | ྜ | ྜྷ | ྞ | ྟ | |

| U+0FAx | ྠ | ྡ | ྡྷ | ྣ | ྤ | ྥ | ྦ | ྦྷ | ྨ | ྩ | ྪ | ྫ | ྫྷ | ྭ | ྮ | ྯ |

| U+0FBx | ྰ | ྱ | ྲ | ླ | ྴ | ྵ | ྶ | ྷ | ྸ | ྐྵ | ྺ | ྻ | ྼ | ྾ | ྿ | |

| U+0FCx | ࿀ | ࿁ | ࿂ | ࿃ | ࿄ | ࿅ | ࿆ | ࿇ | ࿈ | ࿉ | ࿊ | ࿋ | ࿌ | ࿎ | ࿏ | |

| U+0FDx | ࿐ | ࿑ | ࿒ | ࿓ | ࿔ | ࿕ | ࿖ | ࿗ | ࿘ | ࿙ | ࿚ | |||||

| U+0FEx | ||||||||||||||||

| U+0FFx | ||||||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See Also

- Tibetan calligraphy

- Tibetan Braille

- Dzongkha Braille

- Tibetan typefaces

- Wylie transliteration

- Tibetan pinyin

- Roman Dzongkha

- THDL Simplified Phonetic Transcription

- Tise, input method for Tibetan script

- Limbu script