Brahmi script facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Brahmi |

|

|---|---|

[[Image: |200x400px]] |200x400px]]

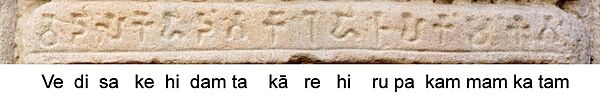

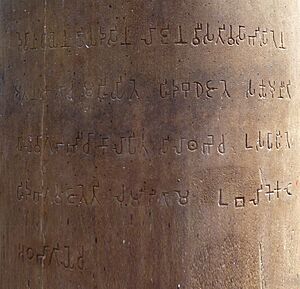

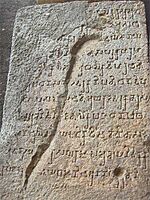

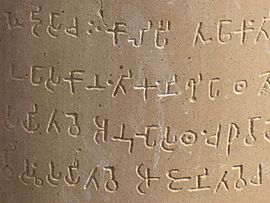

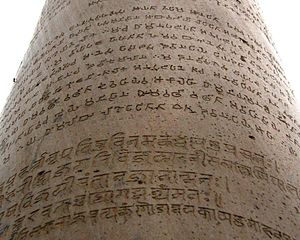

Brahmi script on Ashoka Pillar in Sarnath (c. 250 BCE)

|

|

| Type | Abugida |

| Spoken languages | Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit, Tamil, Saka, Tocharian, Telugu, Elu |

| Time period | At least by the 3rd century BCE to 5th century CE |

| Parent systems | |

| Child systems | Numerous descendant writing systems including:

Devanagari, Kaithi, Sylheti Nagri, Gujarati, Modi, Bengali, Assamese, Sharada, Tirhuta, Odia, Kalinga, Nepalese, Gurmukhi, Khudabadi, Multani, Dogri, Tocharian, Meitei, Lepcha, Tibetan, Bhaiksuki, Siddhaṃ, Takri, ʼPhags-pa |

| Sister systems | Kharosthi |

| Unicode range | U+11000–U+1107F |

| ISO 15924 | Brah |

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | |

Brahmi (/ˈbrɑːmi/ BRAH-mee; 𑀩𑁆𑀭𑀸𑀳𑁆𑀫𑀻) is an ancient writing system from India. It first appeared as a fully developed script around the 3rd century BCE. Many modern writing systems used across Southern and Southeastern Asia today come from Brahmi. These are called Brahmic scripts.

Brahmi is an abugida. This means each letter represents a consonant, and you add small marks (called diacritics) to show which vowel goes with it. The script changed only a little from the Mauryan Empire (3rd century BCE) to the early Gupta Empire (4th century CE). People living in the 4th century CE could still read old Mauryan writings. Later, the ability to read the original Brahmi script was lost. The oldest and most famous Brahmi writings are the rock carvings of edicts of Ashoka in north-central India, from about 250–232 BCE.

In the early 1800s, scholars in Europe became very interested in Brahmi. They wanted to understand its secrets. James Prinsep, a secretary of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, finally figured out how to read Brahmi in the 1830s. His work built on the efforts of other scholars like Christian Lassen and Alexander Cunningham.

The exact origin of Brahmi is still debated. Most experts think it came from, or was at least influenced by, older Semitic scripts. Some people believe it developed entirely in India, possibly linked to the much older and still unreadable Indus script. However, most experts who study ancient writings (epigraphists) do not agree with this idea.

Brahmi was once called the "pin-man" script because its letters looked like stick figures. It had other names too, like "lath" or "Mauryan". In the 1880s, a scholar named Albert Étienne Jean Baptiste Terrien de Lacouperie connected it to the Brahmi script mentioned in an ancient text called the Lalitavistara Sūtra. This name then became widely used.

The Gupta script from the 5th century is sometimes called "Late Brahmi". After the 6th century, Brahmi started to change into many different local versions. These became the Brahmic family of scripts. Today, dozens of modern scripts in South and Southeast Asia come from Brahmi. This makes it one of the most important writing traditions in the world. One study found 198 scripts that can be traced back to Brahmi.

Some numbers, called Brahmi numerals, were found in the inscriptions of Ashoka (around 3rd century BCE). These numbers were added together or multiplied, but they did not use a place-value system like our modern numbers. Later, in the second half of the 1st millennium CE, some inscriptions in India and Southeast Asia used a decimal place-value system. These are the earliest examples of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system that we use worldwide today.

Contents

Ancient Texts Mention Brahmi

The Brahmi script is mentioned in old Indian religious texts. These include writings from Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism. Even Chinese translations of these texts talk about Brahmi.

For example, a Buddhist text called the Lalitavistara Sūtra (written around 200–300 CE) lists 64 different scripts. Brahmi is at the very top of this list. The Lalitavistara Sūtra says that young Siddhartha, who would later become the Gautama Buddha (around 500 BCE), learned Brahmi and other scripts at school.

Early Jaina texts, like the Paṇṇavaṇā Sūtra (2nd century BCE) and the Samavāyāṅga Sūtra (3rd century BCE), also list ancient scripts. These Jain lists include Brahmi as the first script and Kharoṣṭhi as the fourth. They also mention other scripts, including one that might be Greek.

Where Did Brahmi Come From?

The origin of the Brahmi script is a big puzzle for scholars. Another ancient Indian script, Kharoṣṭhī, is widely believed to have come from the Aramaic alphabet. But Brahmi's story is not as clear.

Some early ideas suggested that Brahmi came from pictographic (picture-based) writing, like Egyptian hieroglyphs. However, these ideas are not widely accepted today. Similarly, some tried to connect Brahmi to the Indus script, but this is hard to prove because the Indus script has not been deciphered yet.

Most scholars believe that Brahmi came from, or was influenced by, Semitic scripts. The Aramaic alphabet is a strong candidate. This idea has been popular since the late 1800s. Even then, there were many different theories about Brahmi's origin.

The biggest debate is whether Brahmi was created entirely in India or if it was borrowed from outside. Some Indian scholars prefer the idea of an indigenous (local) origin. Most Western scholars support the idea of a Semitic origin. Some experts believe that both sides might have a bit of bias in their views.

Most scholars agree that even if Brahmi was influenced by a Semitic script, it changed a lot in India. The way it looks and how it works were greatly developed in India. It is also thought that the study of grammar of the Vedic language had a strong impact on how Brahmi developed. Some scholars suggest that Brahmi was borrowed or inspired by a Semitic script and then quickly created during the time of Ashoka. Others completely disagree with the idea of foreign influence.

One scholar, Bruce Trigger, thinks Brahmi probably came from the Aramaic script, but with many changes made in India. He believes Brahmi was used before the Ashoka pillars, possibly as early as the 4th or 5th century BCE in Sri Lanka and India. Kharoṣṭhī, on the other hand, was mainly used in northwest South Asia and died out later.

Semitic Influence Theory

Many scholars connect Brahmi's origin to Semitic scripts, especially Aramaic. How this happened, which specific Semitic script was involved, and when it happened are still debated. Aramaic is a strong candidate because it was used as a government language in the Achaemenid empire, which was geographically close to India. However, it is unclear why two very different scripts, Kharoṣṭhī and Brahmi, would have developed from the same Aramaic source.

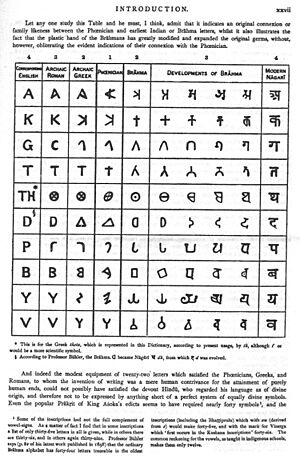

The table below shows how similar Brahmi letters are to the first four letters of the Phoenician alphabet, a Semitic script.

| Letter | Name | Phoneme | Origin | Corresponding letter in | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Text | Hieroglyphs | Proto-Sinaitic | Aramaic | Hebrew | Syriac | Greek | Brahmi | |||||||||

| 𐤀 | ʾālep | ʾ [ʔ] | 𓃾 | 𐡀 | א | ܐ | Αα | 𑀅 | |||||||||

| 𐤁 | bēt | b [b] | 𓉐 | 𐡁 | ב | ܒ | Ββ | 𑀩 | |||||||||

| 𐤂 | gīml | g [ɡ] | 𓌙 | 𐡂 | ג | ܓ | Γγ | 𑀕 | |||||||||

| 𐤃 | dālet | d [d] | 𓇯 | 𐡃 | ד | ܕ | Δδ | 𑀥 | |||||||||

Bühler's Idea

| Phoenician | Aramaic | Value | Brahmi | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| * | a | |||

| b [b] | ba | |||

| g [ɡ] | ga | |||

| d [d] | dha | |||

| h [h], M.L. | ha | |||

| w [w], M.L. | va | |||

| z [z] | ja | |||

| ḥ [ħ] | gha | |||

| ṭ [tˤ] | tha | |||

| y [j], M.L. | ya | |||

| k [k] | ka | |||

| l [l] | la | |||

| m [m] | ma | |||

| n [n] | na | |||

| s [s] | ṣa | |||

| ʿ [ʕ], M.L. | e | |||

| p [p] | pa | |||

| ṣ [sˤ] | ca | |||

| q [q] | kha | |||

| r [r] | ra | |||

| š [ʃ] | śa | |||

| t [t] | ta |

A scholar named Bühler suggested in 1898 that the oldest Brahmi inscriptions came from a Phoenician script. However, later discoveries of Aramaic inscriptions from the Mauryan period suggest that Aramaic might be a more likely source. It is still a mystery why two very different scripts (Kharoṣṭhī and Brahmi) would come from the same Aramaic source.

Bühler believed that Brahmi added new symbols for sounds not found in Semitic languages. It also changed or reused symbols for Semitic sounds that were not needed in Prakrit (an ancient Indian language). For example, Aramaic did not have certain sounds found in Prakrit, and Brahmi's letters for these sounds look very similar to each other, as if they came from one original letter.

One challenge with the Phoenician theory is the lack of proof that Phoenicians and Indians had much contact during that time. Bühler explained this by suggesting that Brahmi was borrowed much earlier, around 800 BCE.

Another piece of evidence for Persian influence is the word for writing itself, lipi, in Prakrit/Sanskrit. It is similar to the Old Persian word dipi. Some of Ashoka's edicts use dipi in areas closer to the Persian empire, and lipi elsewhere. This suggests that lipi might be a changed version of dipi as the idea of writing spread.

Greek and Semitic Influences?

A scholar named Harry Falk suggested in 1993 that Brahmi's basic writing system came from the Kharoṣṭhī script, which itself came from Aramaic. He also thought that Greek might have played a role in Brahmi's development. However, other scholars disagree with the idea of strong Greek influence. They point out big differences in how Greek and Brahmi show vowels.

More recently, in 2018, Harry Falk updated his view. He now believes Brahmi was created from scratch during Ashoka's time. He thinks it combined the good points of the Greek script (like broad, upright letters and writing from left to right) and the northern Kharosthi script (like its way of handling vowels). A new system for combining consonants was also developed.

Indigenous Origin Theory

Some scholars, both Western and Indian, support the idea that Brahmi originated in India. They suggest a connection to the Indus script. Early European scholars like John Marshall also saw similarities. G. R. Hunter even proposed that Brahmi came from the Indus script, finding more matches than with Aramaic.

British archaeologist Raymond Allchin argued against the Semitic borrowing idea. He said Brahmi's structure is very different. He once thought Brahmi might be purely indigenous, with the Indus script as its ancestor. However, he later said there wasn't enough evidence to be sure.

Today, the indigenous origin theory is often supported by non-specialists. They point to similarities between Brahmi and the late Indus script. For example, the ten most common combined letters in Brahmi match the form of ten common symbols in the Indus script. There is also evidence of continuity in how numbers were used.

The main problem with this theory is a huge time gap. There is no clear evidence of writing for about 1,500 years between the end of the Indus Valley civilisation (around 1500 BCE) and the first widely accepted appearance of Brahmi (3rd or 4th centuries BCE). Also, the Indus script is still not deciphered, making theories based on it hard to prove.

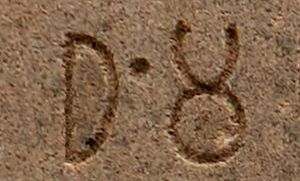

A possible link between the Indus script and later writing might be the megalithic graffiti symbols found in South India. These symbols might overlap with Indus symbols and were used until Brahmi appeared. These graffiti marks were usually single symbols, possibly representing families or religious groups.

Another idea is that Brahmi was invented completely new, without any influence from Semitic scripts or the Indus script. However, scholars find these theories to be mostly guesswork.

Foreign Influence on the Word "Lipi"

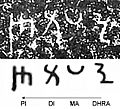

𑀮La+𑀺i; pī=𑀧Pa+𑀻ii). The word would be of Old Persian origin ("Dipi").Pāṇini, a famous Sanskrit grammarian (6th to 4th century BCE), mentions lipi, the Indian word for writing scripts. Some scholars believe lipi and libi were borrowed from the Old Persian word dipi, which itself came from a Sumerian word. Ashoka used the word Lipī to describe his own Edicts, meaning "writing" or "inscription". This word appears as dipi in two of his edicts written in the Kharosthi script, which were found in areas closer to the Persian empire. This suggests the word might have spread from Persia.

Some scholars argue that no script was used in India before 300 BCE, except in the Persian-influenced Northwest where Aramaic was used. They say Indian traditions always emphasized oral (spoken) learning. However, the same scholars admit that the Indus Valley Civilization had a script, though it is undeciphered.

Megasthenes' Observations

Megasthenes, a Greek ambassador who visited the Mauryan court in India before Ashoka, wrote that the people had "no written laws, who are ignorant even of writing, and regulate everything by memory." This statement has been interpreted in many ways.

Some scholars believe Megasthenes might have misunderstood. He might have thought they were illiterate because their laws were not written down, and oral traditions were very important. Other scholars question how reliable Megasthenes' writings are. Another Greek, Nearchus, who was around at the same time, noted that cotton fabric was used for writing in Northern India. Scholars have wondered if this was Kharoṣṭhī or Aramaic. The evidence from Greek sources is not conclusive.

When Did Brahmi Appear?

Some scholars, like K. R. Norman, suggest that Brahmi was developed over a longer period before Ashoka's rule. This idea is supported by discoveries of Brahmi characters on pottery fragments in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka. These fragments have been dated to possibly two centuries before Ashoka, though these findings are debated.

Norman also notes that the different styles seen in Ashoka's edicts would not have appeared so quickly if Brahmi had been created all at once. He suggests Brahmi developed by the end of the 4th century BCE, with even earlier forms possible.

Jack Goody (1987) also suggested that ancient India likely had a "very old culture of writing" alongside its oral traditions. He thought the vast and complex Vedic literature would have been too difficult to create, memorize, and spread accurately without writing.

However, opinions on this are divided. Some scholars believe the Vedic hymns could have been passed down orally. Others, like Johannes Bronkhorst, think that the development of Panini's complex grammar would have required writing.

Origin of the Name "Brahmi"

The name "Brahmi" (ब्राह्मी) has different origins in history. In Sanskrit, it is a feminine word meaning "of Brahma" or "the female energy of the Brahman". In Hindu texts like the Mahabharata, it refers to a goddess, often Saraswati, the goddess of speech. Later Chinese Buddhist accounts also link its creation to the god Brahma. Some scholars think it was named Brahmi because Brahmins (priests and scholars) shaped it.

Another story comes from Buddhist texts like the Lalitavistara Sūtra (possibly 4th century CE). It lists Brāhmī and Kharoṣṭī as two of the 64 scripts the Buddha knew as a child. Several Jain texts also list 18 ancient scripts, with Bambhi (बाम्भी) at the top. Jain legend says that the first Tirthankara, Rishabhanatha, taught 18 scripts to his daughter Bambhi. She emphasized Bambhi as the main script, and so the script was named after her.

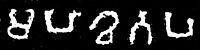

There is no early proof from inscriptions for the name "Brahmi script". When Ashoka created the first known inscriptions in this new script in the 3rd century BCE, he used the phrase dhaṃma lipi (𑀥𑀁𑀫𑀮𑀺𑀧𑀺, "Inscriptions of the Dharma"). This phrase described his edicts, not the script itself.

History of Brahmi

The earliest complete Brahmi inscriptions are in Prakrit language, dating from the 3rd to 1st centuries BCE. The most famous are the Edicts of Ashoka, around 250 BCE. Prakrit writings are most common in India until about the 1st century CE. The first known Brahmi inscriptions in Sanskrit are from the 1st century BCE. These were found in places like Ayodhya and Ghosundi.

Ancient Brahmi writings have been found on pillars, temple walls, metal plates, pottery, coins, and even crystals.

Recently, Brahmi characters were found on pottery in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka. These have been dated to between the 6th and early 4th century BCE, though this is debated. Some scholars believe these findings support the idea that Brahmi existed in South Asia before Ashoka's time. However, others question if these inscriptions are truly that old.

In 2013, new excavations in Tamil Nadu found many Tamil-Brahmi and "Prakrit-Brahmi" inscriptions. Their dating suggests they could be as old as the 6th or 7th centuries BCE. These findings are very new and are still being discussed by scholars. Some argue that the earliest marks might just be non-linguistic symbols, not actual Brahmi letters.

How Brahmi Changed Over Time

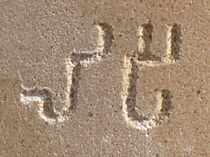

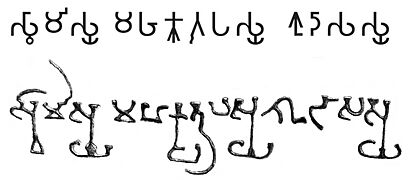

The text is Svāmisya Mahakṣatrapasya Śudasasya

"Of the Lord and Great Satrap Śudāsa"

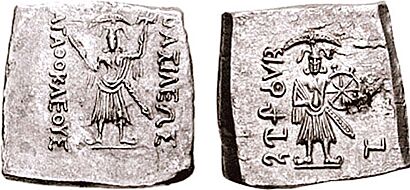

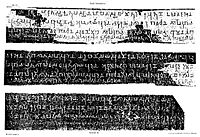

The way Brahmi letters were written stayed mostly the same from the Maurya Empire until the end of the 1st century BCE. Around that time, the Indo-Scythians (also called "Northern Satraps") came to northern India and made "revolutionary changes" to Brahmi.

In the 1st century BCE, Brahmi letters became more angular. The vertical parts of the letters became more equal in length. This made the script look more like the Greek script. This new style is clear in coin inscriptions and made the writing "neat and well-formed." It is thought that writing with ink and pen became more common, which influenced the look of letters carved in stone. This new style spread across India in the next 50 years. It led to a quick evolution of the script from the 1st century CE, with different regional styles starting to appear.

How Brahmi Was Deciphered

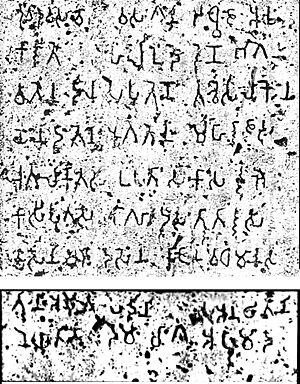

The Edicts of Ashoka were written in Brahmi and sometimes in the Kharoshthi script. Both scripts died out around the 4th century CE and could not be read when the edicts were found in the 1800s.

Earlier Brahmi inscriptions from the 6th century CE were deciphered in 1785 by Charles Wilkins. He used similarities with later Brahmic scripts like Devanagari. But the older Brahmi from Ashoka's time remained a mystery.

Progress began in 1834 when good copies of the inscriptions on the Allahabad pillar of Ashoka were published. These included Ashoka's edicts and writings by the Gupta Empire ruler Samudragupta.

James Prinsep, an archaeologist, started to study these inscriptions. He used statistical methods to figure out the general features of early Brahmi. He realized that Brahmi letters represented consonants with vowel "inflections" (small marks). He correctly guessed four out of five vowel marks, but the consonant values were still unknown.

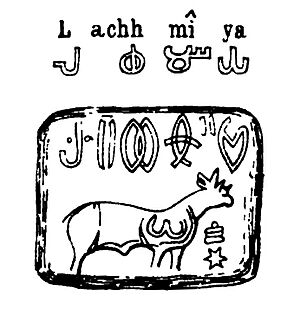

The big breakthrough came in 1836. A Norwegian scholar, Christian Lassen, used a coin with writing in both Greek and Brahmi from the Indo-Greek king Agathocles. By comparing the two languages, he correctly identified several Brahmi letters.

James Prinsep then completed the decipherment. He used another bilingual coin, this time from King Pantaleon, to figure out more letters. Prinsep also studied many inscriptions at Sanchi. He noticed that most of them ended with the same two Brahmi characters: "𑀤𑀦𑀁". He correctly guessed that this meant "danam", which is the Sanskrit word for "gift" or "donation". This helped him identify even more letters. With the help of a Pali scholar, Prinsep finally deciphered the entire Brahmi script. In 1838, he published his findings, providing a nearly perfect understanding of the full Brahmi alphabet.

Southern Brahmi

Ashokan inscriptions are found all over India, and some regional differences have been noticed. The Bhattiprolu alphabet, which appeared shortly after Ashoka's reign, is thought to have come from a southern style of Brahmi. The language in these inscriptions is mostly Prakrit, but some Kannada and Telugu names have been found.

Tamil-Brahmi is a version of the Brahmi alphabet used in South India, especially in Tamil Nadu and Kerala, by about the 3rd century BCE. Inscriptions also show its use in parts of Sri Lanka during the same time. Most of the early inscriptions in Sri Lanka are found above caves. The language of Sri Lanka Brahmi inscriptions is mainly Prakrit, but some Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions have also been found. The earliest widely accepted examples of Brahmi writing are in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka.

Brahmi in Red Sea and Southeast Asia

Brahmi script has been found far from India. The Khuan Luk Pat inscription in Thailand is in Tamil Brahmi script. Its exact date is unknown, but it might be from the early centuries CE. Tamil Brahmi inscriptions on pottery have also been found in Egypt (Quseir al-Qadim and Berenike). This shows that there was a lot of trade between India and the Red Sea region in ancient times. Another Tamil Brahmi inscription was found in Oman.

How Brahmi Works

Brahmi is usually written from left to right, just like most of the scripts that came from it. However, one early coin found in Eran has Brahmi written from right to left, similar to Aramaic. Other examples of different writing directions exist, but this was common in ancient writing systems.

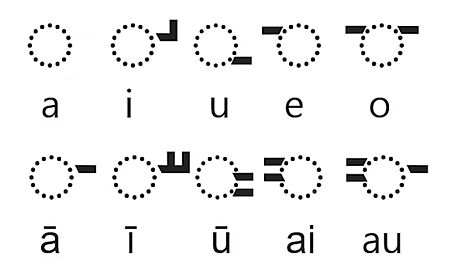

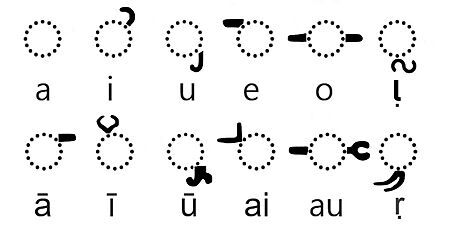

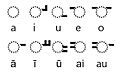

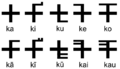

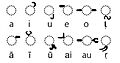

Consonants and Vowels

Brahmi is an abugida. This means that each main letter stands for a consonant sound, and it automatically includes a short 'a' vowel sound. If you want a different vowel, you add a small mark (a diacritic) to the consonant letter. For example, the letter for 'k' would be 'ka' by default. To make it 'ki' or 'ku', you add a special mark. Vowels that start a word have their own separate letters.

There were three main vowels in Ashokan Brahmi: /a/, /i/, /u/. Each of these could be short or long. Long vowels were made by changing the letters for short vowels. There were also four "secondary" vowels: /e:/, /ai/, /o:/, /au/.

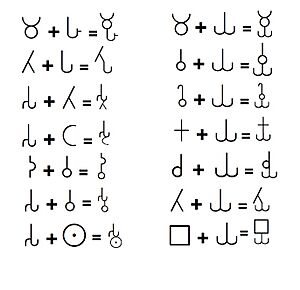

Combining Consonants

When two or more consonants come together without a vowel in between (like 'pr' in "pray" or 'rv' in "river"), special combined letters called conjunct consonants are used. In modern scripts like Devanagari, these are often written side-by-side. But in Brahmi, the letters were usually stacked vertically, one below the other.

Punctuation Marks

In early Brahmi, punctuation marks were not used very often. Sometimes there were spaces between words, especially in public pillar inscriptions. But the idea of writing each word separately was not always followed.

In the middle period of Brahmi, punctuation started to develop. You can find dashes and curved lines. A lotus flower mark might have shown the end of a section, and a circular mark might have been a full stop.

In the late period, punctuation became more complex. There were different forms of double vertical dashes, like "//", to show the end of a composition. Even with many decorative signs available, the marks in inscriptions stayed quite simple. This might be because carving detailed signs was harder than writing them.

Scholars have identified seven different punctuation marks for Brahmi in computer systems:

- Single (𑁇) and double (𑁈) vertical bars – to separate parts of sentences or verses.

- Dot (𑁉), double dot (𑁊), and horizontal line (𑁋) – to separate shorter text units.

- Crescent (𑁌) and lotus (𑁍) – to separate larger text units.

How Brahmi Changed Over Time

Brahmi is generally divided into three main types, showing how it changed over nearly a thousand years:

- Early Brahmi (or "Ashokan Brahmi"): 3rd-1st century BCE

- Middle Brahmi (or "Kushana Brahmi"): 1st-3rd centuries CE

- Late Brahmi (or Gupta Brahmi): 4th-6th centuries CE

| Evolution of the Brahmi script | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k- | kh- | g- | gh- | ṅ- | c- | ch- | j- | jh- | ñ- | ṭ- | ṭh- | ḍ- | ḍh- | ṇ- | t- | th- | d- | dh- | n- | p- | ph- | b- | bh- | m- | y- | r- | l- | v- | ś- | ṣ- | s- | h- | |

| Ashoka | 𑀓 | 𑀔 | 𑀕 | 𑀖 | 𑀗 | 𑀘 | 𑀙 | 𑀚 | 𑀛 | 𑀜 | 𑀝 | 𑀞 | 𑀟 | 𑀠 | 𑀡 | 𑀢 | 𑀣 | 𑀤 | 𑀥 | 𑀦 | 𑀧 | 𑀨 | 𑀩 | 𑀪 | 𑀫 | 𑀬 | 𑀭 | 𑀮 | 𑀯 | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | 𑀲 | 𑀳 |

| Girnar | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kushan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gujarat | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gupta | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Early Brahmi (Ashokan Brahmi)

Early Brahmi (3rd–1st century BCE) looks very neat and geometric. It was organized in a very logical way.

Vowel Marks

| Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

Mātrā | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

Mātrā | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𑀅 | a /ɐ/ | 𑀓 | ka /kɐ/ | 𑀆 | ā /aː/ | 𑀓𑀸 | kā /kaː/ |

| 𑀇 | i /i/ | 𑀓𑀺 | ki /ki/ | 𑀈 | ī /iː/ | 𑀓𑀻 | kī /kiː/ |

| 𑀉 | u /u/ | 𑀓𑀼 | ku /ku/ | 𑀊 | ū /uː/ | 𑀓𑀽 | kū /kuː/ |

| 𑀏 | e /eː/ | 𑀓𑁂 | ke /keː/ | 𑀐 | ai /ɐi/ | 𑀓𑁃 | kai /kɐi/ |

| 𑀑 | o /oː/ | 𑀓𑁄 | ko /koː/ | 𑀒 | au /ɐu/ | 𑀓𑁅 | kau /kɐu/ |

Consonant Letters

| Stop | Nasal | Approximant | Fricative | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voicing → | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | ||||||||||||

| Aspiration → | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||||

| Velar | 𑀓 | ka /k/ | 𑀔 | kha /kʰ/ | 𑀕 | ga /ɡ/ | 𑀖 | gha /ɡʱ/ | 𑀗 | ṅa /ŋ/ | 𑀳 | ha /ɦ/ | ||||

| Palatal | 𑀘 | ca /c/ | 𑀙 | cha /cʰ/ | 𑀚 | ja /ɟ/ | 𑀛 | jha /ɟʱ/ | 𑀜 | ña /ɲ/ | 𑀬 | ya /j/ | 𑀰 | śa /ɕ/ | ||

| Retroflex | 𑀝 | ṭa /ʈ/ | 𑀞 | ṭha /ʈʰ/ | 𑀟 | ḍa /ɖ/ | 𑀠 | ḍha /ɖʱ/ | 𑀡 | ṇa /ɳ/ | 𑀭 | ra /r/ | 𑀱 | ṣa /ʂ/ | ||

| Dental | 𑀢 | ta /t̪/ | 𑀣 | tha /t̪ʰ/ | 𑀤 | da /d̪/ | 𑀥 | dha /d̪ʱ/ | 𑀦 | na /n/ | 𑀮 | la /l/ | 𑀲 | sa /s/ | ||

| Labial | 𑀧 | pa /p/ | 𑀨 | pha /pʰ/ | 𑀩 | ba /b/ | 𑀪 | bha /bʱ/ | 𑀫 | ma /m/ | 𑀯 | va /w, ʋ/ | ||||

The final letter is 𑀴 ḷa.

Famous Early Brahmi Inscriptions

The Brahmi script was used for some of the most important ancient Indian inscriptions, starting with the Edicts of Ashoka around 250 BCE.

Buddha's Birthplace Inscription

| Translation (English) |

Transliteration (original Brahmi script) |

Inscription (Prakrit in the Brahmi script) |

|---|---|---|

|

When King Devanampriya Priyadarsin had been anointed twenty years, he came himself and worshipped (this spot) because the Buddha Shakyamuni was born here. (He) both caused to be made a stone bearing a horse (?) and caused a stone pillar to be set up, (in order to show) that the Blessed One was born here. (He) made the village of Lummini free of taxes, and paying (only) an eighth share (of the produce). — The Rummindei Edict, one of the Minor Pillar Edicts of Ashoka. |

𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀸𑀦𑀁𑀧𑀺𑀬𑁂𑀦 𑀧𑀺𑀬𑀤𑀲𑀺𑀦 𑀮𑀸𑀚𑀺𑀦𑀯𑀻𑀲𑀢𑀺𑀯𑀲𑀸𑀪𑀺𑀲𑀺𑀢𑁂𑀦 — Adapted from transliteration by E. Hultzsch |

A very famous edict is the Rummindei Edict in Lumbini, Nepal. In it, Ashoka describes his visit in the 21st year of his rule. He states that he came to worship this spot because the Buddha Shakyamuni was born there. He also mentions setting up a stone pillar to mark the birthplace and making the village of Lummini tax-free.

Heliodorus Pillar Inscription

The Heliodorus pillar is a stone column set up around 113 BCE in central India. It was erected by Heliodorus, an ambassador from the Indo-Greek king Antialcidas to the court of the Shunga king Bhagabhadra. This pillar has one of the earliest known inscriptions in India related to Vaishnavism (a branch of Hinduism).

| Translation (English) |

Transliteration (original Brahmi script) |

Inscription (Prakrit in the Brahmi script) |

|---|---|---|

|

This Garuda-standard of Vāsudeva, the God of Gods Three immortal precepts (footsteps)... when practiced |

𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀲 𑀯𑀸(𑀲𑀼𑀤𑁂)𑀯𑀲 𑀕𑀭𑀼𑀟𑀥𑁆𑀯𑀚𑁄 𑀅𑀬𑀁 — Adapted from transliterations by E. J. Rapson, Sukthankar, Richard Salomon, and Shane Wallace. |

Heliodorus pillar rubbing (inverted colors). The text is in the Brahmi script of the Sunga period. For a recent photograph.

|

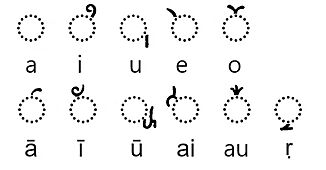

Middle Brahmi (Kushana Brahmi)

Middle Brahmi, also called "Kushana Brahmi," was used from the 1st to 3rd centuries CE. It looks more rounded than Early Brahmi and has some noticeable changes in letter shapes. During this period, new letters for certain vowel sounds (like r̩ and l̩) were added to help write Sanskrit.

Vowel Marks in Middle Brahmi

| Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| a /ə/ | ā /aː/ | ||

| i /i/ | ī /iː/ | ||

| u /u/ | ū /uː/ | ||

| e /eː/ | o /oː/ | ||

| ai /əi/ | au /əu/ | ||

| 𑀋 | ṛ /r̩/ | 𑀌 | ṝ /r̩ː/ |

| 𑀍 | l̩ /l̩/ | 𑀎 | ḹ /l̩ː/ |

Consonant Letters in Middle Brahmi

| Stop | Nasal | Approximant | Fricative | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voicing → | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | ||||||||||||

| Aspiration → | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||||

| Velar | ka /k/ | kha /kʰ/ | ga /g/ | gha /ɡʱ/ | ṅa /ŋ/ | ha /ɦ/ | ||||||||||

| Palatal | ca /c/ | cha /cʰ/ | ja /ɟ/ | jha /ɟʱ/ | ña /ɲ/ | ya /j/ | śa /ɕ/ | |||||||||

| Retroflex | ṭa /ʈ/ | ṭha /ʈʰ/ | ḍa /ɖ/ | ḍha /ɖʱ/ | ṇa /ɳ/ | ra /r/ | ṣa /ʂ/ | |||||||||

| Dental | ta /t̪/ | tha /t̪ʰ/ | da /d̪/ | dha /d̪ʱ/ | na /n/ | la /l/ | sa /s/ | |||||||||

| Labial | pa /p/ | pha /pʰ/ | ba /b/ | bha /bʱ/ | ma /m/ | va /w, ʋ/ | ||||||||||

Examples of Middle Brahmi

-

Inscribed Kushan statue of Western Satraps King Chastana, with inscription "Shastana" in Middle Brahmi script of the Kushan period (

Ṣa-sta-na).

Ṣa-sta-na).

Here, sta is the conjunct consonant of sa

is the conjunct consonant of sa  and ta

and ta  , vertically combined. Circa 100 CE.

, vertically combined. Circa 100 CE. -

The rulers of the Western Satraps were called Mahākhatapa ("Great Satrap") in their Brahmi script inscriptions, as here in a dedicatory inscription by Prime Minister Ayama in the name of his ruler Nahapana, Manmodi Caves, c. 100 CE.

Late Brahmi (Gupta Brahmi)

Late Brahmi, also known as the Gupta script, was used from the 4th to 6th centuries CE.

Vowel Marks in Late Brahmi

| Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| a /ə/ | ā /aː/ | ||

| i /i/ | ī /iː/ | ||

| u /u/ | ū /uː/ | ||

| e /eː/ | o /oː/ | ||

| ai /əi/ | au /əu/ | ||

| 𑀋 | ṛ /r̩/ | 𑀌 | ṝ /r̩ː/ |

| 𑀍 | l̩ /l̩/ | 𑀎 | ḹ /l̩ː/ |

Consonant Letters in Late Brahmi

| Stop | Nasal | Approximant | Fricative | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voicing → | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | ||||||||||||

| Aspiration → | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||||

| Velar | ka /k/ | kha /kʰ/ | ga /g/ | gha /ɡʱ/ | ṅa /ŋ/ | ha /ɦ/ | ||||||||||

| Palatal | ca /c/ | cha /cʰ/ | ja /ɟ/ | jha /ɟʱ/ | ña /ɲ/ | ya /j/ | śa /ɕ/ | |||||||||

| Retroflex | ṭa /ʈ/ | ṭha /ʈʰ/ | ḍa /ɖ/ | ḍha /ɖʱ/ | ṇa /ɳ/ | ra /r/ | ṣa /ʂ/ | |||||||||

| Dental | ta /t̪/ | tha /t̪ʰ/ | da /d̪/ | dha /d̪ʱ/ | na /n/ | la /l/ | sa /s/ | |||||||||

| Labial | pa /p/ | pha /pʰ/ | ba /b/ | bha /bʱ/ | ma /m/ | va /w, ʋ/ | ||||||||||

Examples of Late Brahmi

Scripts That Came From Brahmi

Over about a thousand years, Brahmi changed and developed into many different regional scripts. These scripts then became linked to the local languages.

- Northern Brahmi led to the Gupta script during the Gupta Empire. This is sometimes called "Late Brahmi" (used in the 5th century). The Gupta script then branched out into many cursive (flowing) scripts in the Middle Ages, like the Siddhaṃ script (6th century) and Śāradā script (9th century).

- Southern Brahmi led to the Grantha alphabet (6th century) and the Vatteluttu alphabet (8th century). Because of Hinduism's spread to Southeast Asia, Southern Brahmi also influenced scripts like Baybayin in the Philippines, the Javanese script in Indonesia, the Khmer alphabet in Cambodia, and the Old Mon script in Burma.

- The Brahmi family also includes several scripts from Central Asia, such as Tibetan, Tocharian, and the script used for the Saka language.

- Brahmi also evolved into the Nagari script, which then became Devanagari and Nandinagari. Both were used for Sanskrit. Devanagari is now widely used in India for Sanskrit, Marathi, Hindi, and Konkani.

The way Brahmi letters are ordered was adopted for the modern order of Japanese kana, even though the letters themselves are not related.

| k- | kh- | g- | gh- | ṅ- | c- | ch- | j- | jh- | ñ- | ṭ- | ṭh- | ḍ- | ḍh- | ṇ- | t- | th- | d- | dh- | n- | p- | ph- | b- | bh- | m- | y- | r- | l- | v- | ś- | ṣ- | s- | h- | |

| Brahmi | 𑀓 | 𑀔 | 𑀕 | 𑀖 | 𑀗 | 𑀘 | 𑀙 | 𑀚 | 𑀛 | 𑀜 | 𑀝 | 𑀞 | 𑀟 | 𑀠 | 𑀡 | 𑀢 | 𑀣 | 𑀤 | 𑀥 | 𑀦 | 𑀧 | 𑀨 | 𑀩 | 𑀪 | 𑀫 | 𑀬 | 𑀭 | 𑀮 | 𑀯 | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | 𑀲 | 𑀳 |

| Gupta | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Devanagari | क | ख | ग | घ | ङ | च | छ | ज | झ | ञ | ट | ठ | ड | ढ | ण | त | थ | द | ध | न | प | फ | ब | भ | म | य | र | ल | व | श | ष | स | ह |

Possible Connections to Other Scripts

Some scholars have suggested that some basic letters of hangul (the Korean alphabet) might have been influenced by the 'Phags-pa script. The 'Phags-pa script came from the Tibetan alphabet, which is a Brahmi script. However, one of the main scholars who proposed this, Gari Ledyard, warns that 'Phags-pa's role in Hangul's development was quite limited. He states that Hangul's origin is complex, combining influences from 'Phags-pa and abstract drawings of how sounds are made.

Brahmi in Computers (Unicode)

Early Ashokan Brahmi was added to the Unicode Standard in October 2010, with version 6.0.

The Unicode block for Brahmi is U+11000–U+1107F. This means computers can now display Brahmi characters. As of June 2022, there are a few fonts that support Brahmi, like Noto Sans Brahmi and Adinatha (which mainly covers Tamil Brahmi). Segoe UI Historic, used in Windows 10, also has Brahmi letters.

The Sanskrit word for Brahmi, ब्राह्मी (IAST Brāhmī), looks like this in the Brahmi script: 𑀩𑁆𑀭𑀸𑀳𑁆𑀫𑀻.

| Brahmi[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart: https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U11000.pdf (PDF) |

||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1100x | 𑀀 | 𑀁 | 𑀂 | 𑀃 | 𑀄 | 𑀅 | 𑀆 | 𑀇 | 𑀈 | 𑀉 | 𑀊 | 𑀋 | 𑀌 | 𑀍 | 𑀎 | 𑀏 |

| U+1101x | 𑀐 | 𑀑 | 𑀒 | 𑀓 | 𑀔 | 𑀕 | 𑀖 | 𑀗 | 𑀘 | 𑀙 | 𑀚 | 𑀛 | 𑀜 | 𑀝 | 𑀞 | 𑀟 |

| U+1102x | 𑀠 | 𑀡 | 𑀢 | 𑀣 | 𑀤 | 𑀥 | 𑀦 | 𑀧 | 𑀨 | 𑀩 | 𑀪 | 𑀫 | 𑀬 | 𑀭 | 𑀮 | 𑀯 |

| U+1103x | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | 𑀲 | 𑀳 | 𑀴 | 𑀵 | 𑀶 | 𑀷 | 𑀸 | 𑀹 | 𑀺 | 𑀻 | 𑀼 | 𑀽 | 𑀾 | 𑀿 |

| U+1104x | 𑁀 | 𑁁 | 𑁂 | 𑁃 | 𑁄 | 𑁅 | 𑁆 | 𑁇 | 𑁈 | 𑁉 | 𑁊 | 𑁋 | 𑁌 | 𑁍 | ||

| U+1105x | 𑁒 | 𑁓 | 𑁔 | 𑁕 | 𑁖 | 𑁗 | 𑁘 | 𑁙 | 𑁚 | 𑁛 | 𑁜 | 𑁝 | 𑁞 | 𑁟 | ||

| U+1106x | 𑁠 | 𑁡 | 𑁢 | 𑁣 | 𑁤 | 𑁥 | 𑁦 | 𑁧 | 𑁨 | 𑁩 | 𑁪 | 𑁫 | 𑁬 | 𑁭 | 𑁮 | 𑁯 |

| U+1107x | 𑁰 | 𑁱 | 𑁲 | 𑁳 | 𑁴 | 𑁵 | BNJ | |||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Images for kids

-

Heliodorus pillar in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. Installed about 113 BCE and now named after Heliodorus, who was an ambassador of the Indo-Greek king Antialcidas from Taxila, and was sent to the Indian ruler Bhagabhadra. The pillar's Brahmi-script inscription states that Heliodorus is a Bhagvatena (devotee) of Vāsudeva. A couplet in it closely paraphrases a Sanskrit verse from the Mahabharata.

-

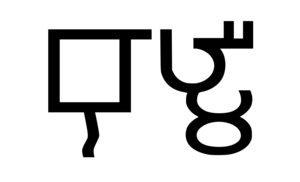

"Dhrama-Dipi" in Kharosthi script.

See also

- Early Indian epigraphy

- Lipi

- Pre-Islamic scripts in Afghanistan

- Shankhalipi

- Tamil-Brahmi

- Anaikoddai seal

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |