James Prinsep facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James Prinsep

|

|

|---|---|

James Prinsep in medal cast c.1840 from the National Portrait Gallery

|

|

| Born | 20 August 1799 England

|

| Died | 22 April 1840 (aged 40) London, England

|

| Academic work | |

| Main interests | Numismatics, Philology, Metallurgy and Meteorology |

| Notable works | Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal |

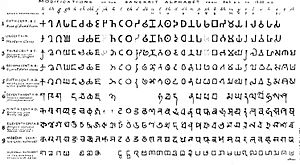

| Notable ideas | Deciphering Kharosthi and Brahmi scripts |

James Prinsep (born August 20, 1799 – died April 22, 1840) was an English expert who studied ancient cultures and languages. He was a founding editor of the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. James Prinsep is best known for figuring out how to read the ancient Kharosthi and Brahmi scripts of India. He also studied coins, metals, and weather. He worked in India as an expert who tested the purity of metals at a mint in Benares.

Contents

Early Life and Education

James Prinsep was the seventh son in a large family. His father, John Prinsep, went to India with little money. He became very successful growing indigo, a plant used to make blue dye. John Prinsep returned to England with a lot of money. He then became a merchant for the East India Company, a powerful trading company.

James first went to school in Clifton. But he learned more at home from his older brothers and sisters. He was very good at drawing detailed pictures. He also had a talent for inventing mechanical things. This led him to study architecture. However, an eye infection made his eyesight worse. Because of this, he could not become an architect. His father helped him get a job in India. James trained in chemistry and learned how to test metals.

Career in India: A Scientific Mind

James Prinsep became an assay master at the Calcutta mint. This meant he tested the purity of metals used for coins. He arrived in Calcutta, India, in September 1819. After a year, he moved to Benares to work at the mint there. He stayed in Benares until 1830 when that mint closed.

He then returned to Calcutta. In 1832, he became the chief assay master at the new silver mint. This mint was designed in a Greek style.

His job led him to do many scientific studies. He found ways to measure very high temperatures in furnaces. He published his method in a famous scientific paper in 1828. This led to him becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society, a group of top scientists. He also designed a very sensitive balance. It could measure tiny amounts of weight, like 0.19 milligrams.

Architecture and City Planning

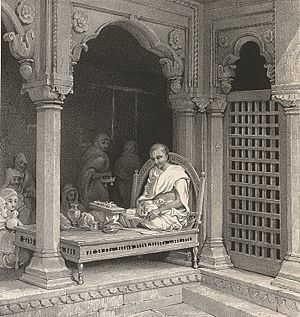

James Prinsep kept his interest in architecture. His eyesight improved, and he studied and drew many temple buildings. He designed the new mint building in Benares. He also designed a church. In 1822, he created a very accurate map of Benares.

He also helped improve the city. He designed a tunnel to drain dirty lakes. This helped make crowded areas of Benares cleaner. He also built a stone bridge over the Karamansa river. He even helped fix the minarets (tall towers) of Aurangzeb's mosque, which were falling apart.

Leading the Asiatic Society Journal

In 1829, a science journal called Gleanings in Science started. James Prinsep soon became its main writer and editor. In 1832, he became the secretary of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. He suggested that the Society take over the journal. This led to the creation of the Journal of the Asiatic Society.

Prinsep was the first editor of this new journal. He wrote articles on many topics. These included chemistry, minerals, coins, and ancient Indian objects. He was also very interested in weather. He collected and analyzed weather data from all over India. He worked on improving instruments that measure humidity and air pressure. He continued to edit the journal until he became ill in 1838.

Coin Expert (Numismatist)

Coins were one of Prinsep's first interests. He studied coins from different ancient empires. These included coins from Bactria, the Kushan Empire, and early Indian coins. He suggested that coins were made in three ways: by punching, by striking with a die, and by casting. He noted that "punch-marked" coins were more common in eastern India.

Cracking Ancient Scripts: Brahmi and Kharosthi

As the editor of the Asiatic Society's journal, Prinsep received copies of coins and inscriptions from all over India. His job was to figure out what they said, translate them, and publish them.

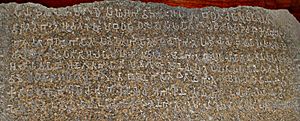

Deciphering the Brahmi script became a major goal for European scholars in the early 1800s. Prinsep, as the secretary of the Asiatic Society, finally cracked the code. He published his findings in the Society's journal between 1836 and 1838. His work built on the efforts of other scholars.

The inscriptions in Brahmi script mentioned a king named Devanampriya Piyadasi. Prinsep first thought this was a king from Sri Lanka. Later, he realized this title belonged to Ashoka, a famous ancient Indian emperor. He figured this out using texts from Sri Lanka. These scripts were found on pillars and rocks across India. Prinsep also deciphered the Kharosthi script found on coins and inscriptions in northwest India.

Prinsep suggested creating a collection of all Indian inscriptions. This project was later formally started by Sir Alexander Cunningham in 1877. Prinsep's studies helped set the dates for ancient Indian dynasties. He did this by looking at references to Greek rulers like Antiochus.

Prinsep also studied the early history of Afghanistan. He wrote about archaeological finds from that country. Many of these finds were sent to him by Alexander Burnes. After James Prinsep died, his brother Henry Thoby Prinsep published a book about James's work on these collections.

Other Interests and Talents

Prinsep was a very talented artist and draftsman. He made detailed drawings of ancient buildings, astronomy tools, fossils, and other subjects. He was also very interested in understanding the weather. He designed a special barometer that could automatically adjust for temperature changes. He kept detailed weather records. He also experimented with ways to stop iron surfaces from rusting.

Personal Life and Family

James Prinsep married Harriet Sophia Aubert in Calcutta on April 25, 1835. They had one daughter, Eliza, in 1837. She was their only child to survive. In 1839, he was chosen as a member of the American Philosophical Society.

Death and Lasting Legacy

James Prinsep worked extremely hard. From 1838, he began to suffer from bad headaches and sickness. It was thought to be a liver problem. He had to stop his studies and left for England in November 1838. He arrived in England in poor health and never recovered. He died on April 22, 1840, in London. Doctors said he died from a "softening of the brain." A type of plant, Prinsepia, was named after him in 1839. This was to honor his work.

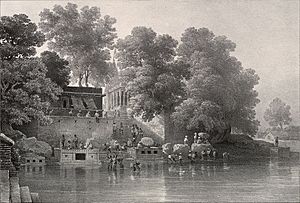

When news of his death reached India, many memorials were planned. A statue of him was made for the Asiatic Society. Prinsep Ghat, a beautiful building on the bank of the Hooghly River in Calcutta, was built in his memory. It was designed in 1843. Some of his original collection of ancient coins and artifacts from India is now in the British Museum in London.

See also

- William Jones

- Allahabad Pillar

Other sources

- Kejariwal, O. P. (1993), The Prinseps of India: A Personal Quest. The Indian Archives, 42 (1-2)

- Allbrook, Malcolm (2008), 'Imperial Family': The Prinseps, Empire and Colonial Government in India and Australia, PhD thesis, Griffith University, Australia.

- James Prinsep and O. P. Kejariwal (2009), "Benares Illustrated" and "James Prinsep and Benares" , Pilgrims Publishing, ISBN: 81-7769-400-6.