Aurangzeb facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Aurangzebاورنگزیب |

|

|---|---|

|

|

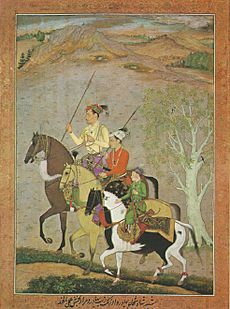

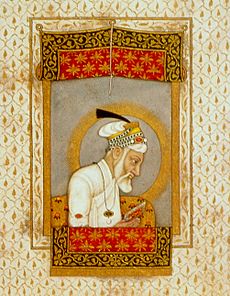

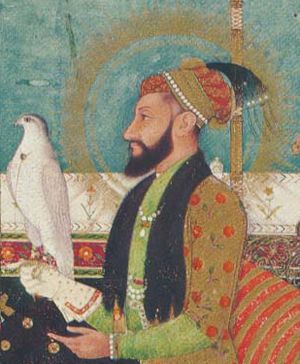

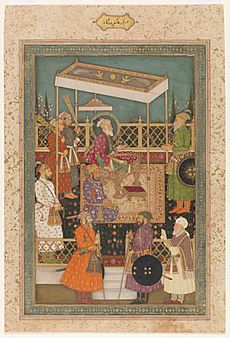

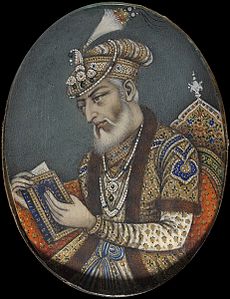

Aurangzeb holding a hawk in c. 1660

|

|

| 6th Mughal Emperor | |

| Sovereignty | 31 July 1658 – 3 March 1707 |

| Predecessor | Shah Jahan |

| Successor | Azam Shah |

| Born | Muhi al-Din Muhammad c. 1618 Dahod, Gujarat |

| Died | 3 March 1707 (aged 88) Ahmednagar, Aurangabad |

| Burial | Tomb of Aurangzeb, Khuldabad |

| Spouse |

|

| Issue |

|

| House | |

| Dynasty | |

| Father | Shah Jahan |

| Mother | Mumtaz Mahal |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

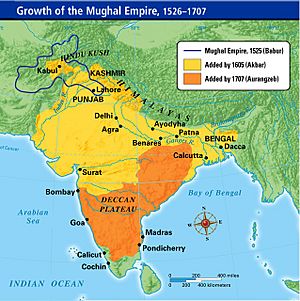

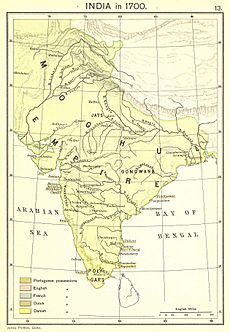

Muhi al-Din Muhammad (Persian: محی الدین محمد, romanized: Muḥī al-Dīn Muḥammad; c. 1618 – 3 March 1707), often called Aurangzeb (meaning "Ornament of the Throne") and by his royal title Alamgir (meaning "Conqueror of the World"), was the sixth emperor of the Mughal Empire. He ruled from July 1658 until his death in 1707. During his time as emperor, the Mughal Empire became its largest, covering almost all of the Indian subcontinent.

Many consider Aurangzeb to be the last powerful Mughal ruler. He created a collection of Islamic laws called the Fatawa 'Alamgiri. He was also one of the few rulers who fully brought Sharia (Islamic law) and Islamic economics into practice across India.

Aurangzeb came from the noble Timurid dynasty. Early in his life, he focused on religious studies. He held important jobs in the army and government under his father, Shah Jahan. He became known as a skilled military leader. Aurangzeb was the viceroy (governor) of the Deccan region from 1636–1637 and governor of Gujarat from 1645–1647. He also managed the provinces of Multan and Sindh and led military trips into nearby Safavid lands.

In September 1657, Shah Jahan chose his oldest son, Dara Shikoh, to be the next emperor. Aurangzeb disagreed with this decision and declared himself emperor in February 1658. In April 1658, Aurangzeb defeated the combined armies of Shikoh and the Kingdom of Marwar at the battle of Dharmat. His big win at the battle of Samugarh in May 1658 made him the clear ruler. After Shah Jahan got better from an illness in July 1658, Aurangzeb said his father was not fit to rule and imprisoned him in the Agra Fort.

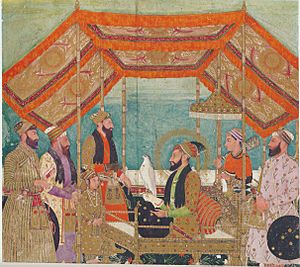

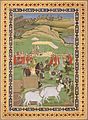

During Aurangzeb's rule, the Mughal Empire grew to its largest size, covering almost all of India. His time as emperor was known for fast military growth, as the Mughals took over many other kingdoms. His victories earned him the title Alamgir ('Conqueror'). The Mughal Empire also became the world's largest economy and biggest manufacturing power, even bigger than Qing China. The Mughal army got stronger and became one of the most powerful armies in the world. Aurangzeb was a strong Muslim. He is known for building many mosques and supporting Arabic calligraphy. He made the Fatawa 'Alamgiri the main set of laws for the empire and stopped activities that were forbidden in Islam. Even though Aurangzeb put down several local uprisings, he kept good relationships with other countries.

Islamic historians often see Aurangzeb as one of the greatest Mughal emperors. While many people admired him during his time, he has been criticized for ordering executions and destroying some Hindu temples. Also, his efforts to make the region more Islamic, bringing back the Jizya tax, and stopping non-Islamic practices caused some unhappiness among non-Muslims. Muslims remember Aurangzeb as a fair ruler and a Mujaddid (a reviver of Islam) of the 11th–12th Islamic century.

Contents

- Aurangzeb: Early Life and Rise to Power

- The War for the Throne

- Aurangzeb's Reign and Policies

- Foreign Relations

- Relations with the Uzbeks

- Relations with the Safavid Dynasty

- Relations with the French

- Relations with the Sultanate of Maldives

- Relations with the Ottoman Empire

- Relations with the English and the Anglo-Mughal War

- Relations with the Ethiopian Empire

- Relations with Tibetans, Uyghurs, and Dzungars

- Relations with the Russian Czardom

- Administrative Changes

- Rebellions During Aurangzeb's Reign

- Death and Legacy

- Full Title

- Literature

- See Also

- Tables

Aurangzeb: Early Life and Rise to Power

Aurangzeb was born in Dahod around c. 1618. His father was Emperor Shah Jahan, who ruled from 1628 to 1658. His family was part of the Mughal dynasty, which came from the Timurid dynasty. This family was descended from Emir Timur, who founded the Timurid Empire. Aurangzeb's mother, Mumtaz Mahal, was the daughter of a Persian nobleman named Asaf Khan. Aurangzeb was born when his grandfather, Jahangir, was the fourth emperor of the Mughal Empire.

In June 1626, after his father's rebellion failed, eight-year-old Aurangzeb and his brother Dara Shikoh were sent to the Mughal court in Lahore. They were held as hostages by their grandfather Jahangir and his wife, Nur Jahan, as part of a deal for their father's forgiveness. After Jahangir died in 1627, Shah Jahan won the fight to become the next Mughal emperor. Aurangzeb and his brother were then reunited with Shah Jahan in Agra.

Aurangzeb received a royal Mughal education. He learned about combat, military plans, and how to run a government. He also studied Islamic subjects, Turkic and Persian literature. Aurangzeb grew up speaking the Hindi of his time very well.

On 28 May 1633, Aurangzeb almost died when a large war elephant charged through the Mughal army camp. He bravely rode towards the elephant and hit its trunk with a lance. He successfully protected himself from being crushed. His father was very impressed by his bravery. Shah Jahan gave him the title Bahadur (Brave) and rewarded him with gifts. This event was celebrated in poems.

Early Military and Government Roles

Aurangzeb was put in charge of the army sent to Bundelkhand. Their goal was to defeat Jhujhar Singh, the rebellious ruler of Orchha. Singh had attacked another area against Shah Jahan's orders. Aurangzeb stayed behind the main fighting and listened to his generals. The Mughal Army surrounded Orchha in 1635. The mission was successful, and Singh was removed from power.

Viceroy of the Deccan

Aurangzeb became the viceroy of the Deccan in 1636. The region had been troubled by the growth of Ahmednagar. Emperor Shah Jahan sent Aurangzeb, who ended the Nizam Shahi dynasty in 1636. In 1637, Aurangzeb married the Safavid princess Dilras Banu. She was his first and favorite wife. In the same year, Aurangzeb was given the task of taking over the small Rajput kingdom of Baglana, which he did easily. In 1638, he married Nawab Bai. That same year, Aurangzeb sent an army to attack the Portuguese fort of Daman. However, his forces faced strong resistance and were pushed back after a long siege. Aurangzeb also married Aurangabadi Mahal, who was from Circassia or Georgia.

In 1644, Aurangzeb's sister, Jahanara, was badly burned in Agra. Aurangzeb did not return to Agra right away, which angered his father. Shah Jahan removed him from his position as viceroy of the Deccan. Some sources say Aurangzeb was removed because he chose to live a simple life as a faqir.

Governor of Gujarat

In 1645, Aurangzeb was kept away from the court for seven months. He shared his sadness with other Mughal commanders. After this, Shah Jahan made him governor of Gujarat. His time in Gujarat had some religious disagreements, but he was praised for bringing stability to the region.

Governor of Balkh

In 1647, Shah Jahan moved Aurangzeb from Gujarat to be governor of Balkh. He replaced his younger brother, Murad Baksh, who had not done well there. The area was being attacked by Uzbek and Turkmen tribes. The Mughal army had strong cannons and guns, but their enemies were also skilled fighters. The two sides were stuck, and Aurangzeb found that his army could not find enough food in the war-torn land. As winter came, he and his father had to make a difficult deal with the Uzbeks, giving up land for a small sign of Mughal power. The Mughal army suffered more attacks as they retreated through the snow to Kabul. This two-year campaign cost a lot of money and gained little.

Aurangzeb then became governor of Multan and Sindh. His attempts in 1649 and 1652 to take back Kandahar from the Safavids failed. The problems of supplying an army far from the capital, along with poor weapons and strong enemies, led to these failures. A third attempt in 1653, led by Dara Shikoh, also failed.

Second Term as Viceroy of the Deccan

Aurangzeb became viceroy of the Deccan again. He felt that Dara Shikoh had tricked his father into replacing him in Kandahar. Aurangzeb's land grants (jagirs) were moved to the Deccan. Because the Deccan was a poorer area, he lost money. Grants from Malwa and Gujarat were needed to keep the government running, which caused tension between father and son. Shah Jahan wanted Aurangzeb to improve farming in the Deccan. Aurangzeb appointed Murshid Quli Khan to use the zabt tax system from northern India in the Deccan. Murshid Quli Khan surveyed farmland and set taxes based on what was produced. To increase income, he gave loans for seeds, animals, and irrigation. The Deccan became prosperous again.

Aurangzeb suggested attacking the rulers of Golconda (the Qutb Shahis) and Bijapur (the Adil Shahis). This would help with money problems and expand Mughal control. Aurangzeb attacked the Sultan of Bijapur and surrounded Bidar. The governor of the city, Sidi Marjan, was badly hurt when a gunpowder storage exploded. After 27 days of hard fighting, Bidar was captured by the Mughals. Aurangzeb continued his advance. Again, he felt Dara had influenced his father. Aurangzeb was frustrated that Shah Jahan chose to negotiate instead of pushing for a complete victory.

The War for the Throne

Shah Jahan had four sons, and all of them were governors. The emperor preferred his oldest son, Dara Shukoh. This made the younger three sons unhappy. They often tried to form alliances against Dara. There was no Mughal rule that the oldest son would automatically become emperor. Instead, it was common for sons to fight their father and for brothers to fight each other to the death. Historians say that strong military leaders and their armies decided who would rule. The main fight for power was between Dara Shikoh and Aurangzeb.

Dara was a thinker and open-minded about religion, like Akbar. Aurangzeb was much more traditional. However, historians say that Dara was not a good general. Also, people's support for either brother was more about their own interests and the leader's appeal than about religious ideas. Muslims and Hindus did not choose sides based on religion.

In 1656, a general under the Qutb Shahi dynasty attacked Aurangzeb, who was surrounding Golconda Fort. Later, Aurangzeb fought an army of 8,000 horsemen and 20,000 musketeers.

Shah Jahan made it clear he wanted Dara to succeed him. In 1657, Shah Jahan became very ill. Dara took care of him in the new city of Shahjahanabad (Old Delhi). Rumors spread that Shah Jahan had died. The younger sons worried that Dara was hiding the truth. So, they took action. Shah Shuja in Bengal crowned himself king and marched his army towards Agra. Near Varanasi, his forces met an army sent from Delhi. Meanwhile, Murad did the same in Gujarat, and Aurangzeb in the Deccan. It's not clear if they truly believed Shah Jahan was dead or if they were just taking advantage of the situation.

After getting better, Shah Jahan moved to Agra. Dara told him to send armies to fight Shah Shuja and Murad. Shah Shuja was defeated in February 1658. The army sent to Murad was surprised to find that he and Aurangzeb had joined forces. The two brothers had agreed to divide the empire once they took control. Their armies fought at Dharmat in April 1658, and Aurangzeb won. Dara realized his forces would not reach Agra in time to stop Aurangzeb. He tried to form new alliances, but Aurangzeb had already won over key people. When Dara's hastily put together army fought Aurangzeb's well-trained army at the battle of Samugarh in May, Dara's men and his leadership were no match. Dara had also become too confident. After Dara's defeat, Shah Jahan was imprisoned in the Agra Fort.

Aurangzeb then broke his agreement with Murad Baksh. He had his brother arrested and imprisoned. Murad was executed in December 1661. Meanwhile, Dara gathered his forces and moved to the Punjab. Aurangzeb offered Shah Shuja the governorship of Bengal. This helped isolate Dara Shikoh and made more troops join Aurangzeb. Shah Shuja, who had declared himself emperor in Bengal, began to take more land. This made Aurangzeb march from Punjab with a new, large army. They fought at the battle of Khajwa, where Shah Shuja's forces were defeated. Shah Shuja then fled to Arakan (in present-day Burma), where he was executed.

With Shuja and Murad gone, and his father imprisoned, Aurangzeb chased Dara Shikoh across the empire. Aurangzeb claimed that Dara was no longer a Muslim. After several battles, Dara was betrayed by one of his generals and captured. In 1658, Aurangzeb was officially crowned emperor in Delhi.

On 10 August 1659, Dara was executed. Aurangzeb also had his allied brother, Prince Murad Baksh, executed. Aurangzeb is also accused of poisoning his nephew Sulaiman Shikoh. After securing his power, Aurangzeb kept his father in the Agra Fort but treated him well. Shah Jahan was cared for by Jahanara and died in 1666.

Aurangzeb's Reign and Policies

Government and Economy

Aurangzeb's government employed many more Hindus than previous emperors. Between 1679 and 1707, the number of Hindu officials in the Mughal government increased by half. They made up 31.6% of the Mughal nobility, the highest ever. Many of them were Marathas and Rajputs, who were his political allies. However, Aurangzeb encouraged high-ranking Hindu officials to convert to Islam.

During his rule, the Mughal Empire produced almost 25% of the world's GDP. This made it the world's largest economy and biggest manufacturing power, even more than all of Western Europe. Its richest part, the Bengal Subah, began to develop early industries.

Islamic Law and Culture

Aurangzeb was a strict Muslim ruler. He tried to make Islam a stronger force in his empire. He was a follower of the Mujaddidi Order and was inspired by a Punjabi saint. He wanted to establish Islamic rule.

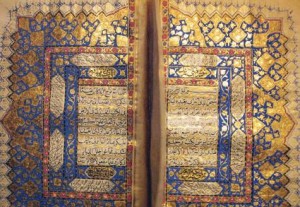

As a traditional leader, Aurangzeb did not follow the more open religious views of the emperors before him. He based his rule on the Quran. Shah Jahan had already moved away from the open-mindedness of Akbar, and Aurangzeb took this change even further.

He created a large collection of Islamic laws called the Fatawa 'Alamgiri. This book was put together by hundreds of legal experts. He learned that in places like Multan, Thatta, and Varanasi, the teachings of Hindu Brahmins attracted many Muslims. He ordered the governors of these areas to destroy schools and temples of non-Muslims. Aurangzeb also ordered governors to punish Muslims who dressed like non-Muslims. The executions of the Sufi mystic Sarmad Kashani and the ninth Sikh Guru Tegh Bahadur show Aurangzeb's religious policy. He also banned the Zoroastrian festival of Nauroz and other non-Islamic ceremonies. He encouraged people to convert to Islam.

Taxes and Temples

Soon after becoming emperor, Aurangzeb removed more than 80 old taxes that affected all his people. In 1679, Aurangzeb decided to bring back the jizya, a military tax on non-Muslims. This tax had not been collected for a hundred years. Many Hindu rulers, Aurangzeb's family members, and Mughal court officials criticized this. The amount of tax depended on a person's wealth. Brahmins, women, children, elders, the disabled, the unemployed, the sick, and the mentally ill were always exempt. The tax collectors had to be Muslims. Most modern scholars believe that this tax was brought back for economic reasons, because of many ongoing wars, and to gain trust with religious scholars, rather than just religious reasons.

Aurangzeb also made Hindu merchants pay a higher tax of 5% compared to 2.5% for Muslim merchants. This caused a lot of dislike for his economic policies. He also increased land taxes to cover government costs, which heavily affected Hindu farmers. The return of the jizya tax encouraged Hindus to move to areas controlled by the East India Company, where there was more religious freedom and no such taxes.

Aurangzeb gave land grants and money to maintain places of worship, but he also sometimes ordered their destruction. Modern historians say that these destructions were not just because of religious passion. Instead, they were often linked to temples being symbols of power and authority.

There are many official orders from Aurangzeb that support temples, monasteries (maths), Sufi shrines, and gurudwaras. These include the Mahakaleshwar temple in Ujjain, a gurudwara in Dehradun, the Balaji temple in Chitrakoot, the Umananda Temple in Guwahati, and the Shatrunjaya Jain temples. Many new temples were also built.

However, court records from that time mention hundreds of temples that were destroyed by Aurangzeb or his leaders. In September 1669, he ordered the destruction of the Kashi Vishwanath Temple in Varanasi. After a rebellion in Mathura in 1670, Aurangzeb ordered the Kesava Deo temple to be destroyed and replaced with an Eidgah (a Muslim prayer ground). Around 1679, he ordered the destruction of several important temples that were supported by rebels.

Historian Richard Eaton, after looking closely at old records, says that 15 temples were destroyed during Aurangzeb's rule. Other historians, like Ian Copland, say that Aurangzeb built more temples than he destroyed.

Executions of Opponents

In 1689, the second Maratha King, Sambhaji, was executed by Aurangzeb. He was found guilty of violence against Muslims. In 1675, the 9th Sikh Guru Tegh Bahadur was arrested on Aurangzeb's orders and later executed because he refused to convert to Islam.

-

In 1689, Sambhaji was put on trial and executed.

-

Guru Tegh Bahadur was publicly executed in 1675 in Delhi.

Expanding the Mughal Empire

In 1663, Aurangzeb took direct control over Ladakh. The local ruler, Deldan Namgyal, agreed to pay tribute and show loyalty. Deldan Namgyal also built a Grand Mosque in Leh for Mughal rule.

In 1664, Aurangzeb appointed Shaista Khan as governor of Bengal. Shaista Khan removed Portuguese and Arakanese pirates from the area. In 1666, he recaptured the port of Chittagong from the Arakanese king. Chittagong remained an important port under Mughal rule.

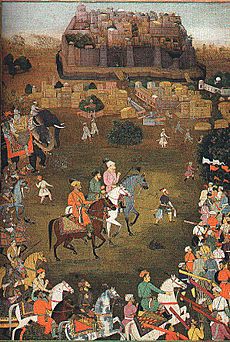

In 1685, Aurangzeb sent his son, Muhammad Azam Shah, with nearly 50,000 men to capture Bijapur Fort. The ruler of Bijapur, Sikandar Adil Shah, refused to become a vassal. The Mughals struggled to advance because both sides had strong cannons. Aurangzeb himself arrived on 4 September 1686 and led the siege of Bijapur. After eight days, the Mughals won.

Only one ruler, Abul Hasan Qutb Shah of Golconda, refused to surrender. He and his men fortified themselves at Golconda. They fiercely protected the Kollur Mine, which was then the world's most productive diamond mine. In 1687, Aurangzeb led his large Mughal army against the Golconda fortress during the siege of Golconda. The Qutbshahis had built massive walls on a granite hill over 400 feet high. The main gates of Golconda could stop any war elephant attack. During the eight-month siege, the Mughals faced many difficulties. Eventually, Aurangzeb's forces broke through the walls by capturing a gate, and Abul Hasan Qutb Shah surrendered peacefully.

Military and Equipment

Mughal cannon-making skills improved during the 1600s. One impressive cannon was the Zafarbaksh, a rare "composite cannon" that combined different metalworking skills.

The Ibrahim Rauza was a famous cannon known for its multiple barrels. François Bernier, Aurangzeb's personal doctor, saw Mughal gun-carriages pulled by two horses.

Despite these new ideas, most soldiers used bows and arrows. The quality of swords made in India was so poor that soldiers preferred swords from England. European gunners, not Mughals, operated the cannons. Other weapons used included rockets, boiling oil, muskets, and manjaniqs (stone-throwing catapults).

Infantry soldiers, later called Sepoy, who specialized in sieges and artillery, became important during Aurangzeb's rule.

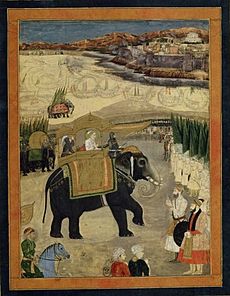

War Elephants

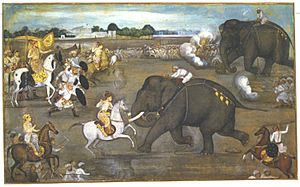

In 1703, the Mughal commander in Coromandel, Daud Khan Panni, spent 10,500 coins to buy 30 to 50 war elephants from Ceylon.

Art and Culture

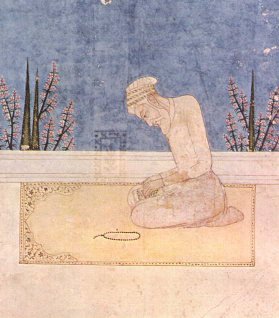

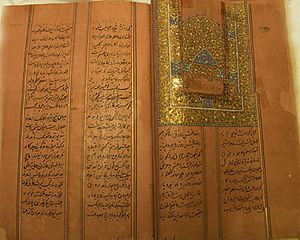

Aurangzeb was known for his strong religious faith. He memorized the entire Quran, studied Islamic traditions (hadiths), and strictly followed Islamic rituals. He also "copied parts of the Quran."

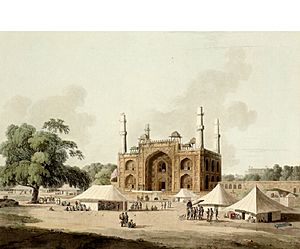

Aurangzeb was more serious than the emperors before him. He greatly reduced royal support for Mughal miniature paintings. This caused artists to move to other regional courts. Being religious, he encouraged Islamic calligraphy. During his rule, the Badshahi Masjid in Lahore and the Bibi Ka Maqbara in Aurangabad (for his wife Rabia-ud-Daurani) were built. Contemporary Muslims considered Aurangzeb a Mujaddid (a reviver of Islam).

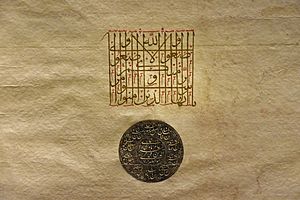

Calligraphy

Emperor Aurangzeb supported works of Islamic calligraphy. The demand for Quran manuscripts in the naskh style was highest during his rule. Aurangzeb himself was a skilled calligrapher in naskh, having been taught by Syed Ali Tabrizi. This is shown in Quran manuscripts he created.

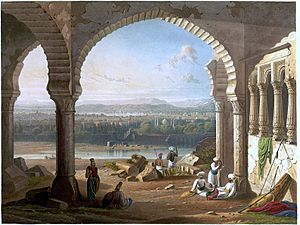

Architecture

Aurangzeb was not as involved in building as his father. During his rule, the Mughal Emperor's role as the main supporter of architecture began to lessen. However, Aurangzeb did fund some important buildings. Catherine Asher calls his architectural period an "Islamization" of Mughal architecture. One of the first buildings after he became emperor was a small marble mosque called the Moti Masjid (Pearl Mosque). It was built for his personal use in the Red Fort complex in Delhi. He later ordered the building of the Badshahi Mosque in Lahore, which is now one of the largest mosques in India. The mosque he built in Srinagar is still the largest in Kashmir.

Most of Aurangzeb's building projects were mosques, but he also built other structures. The Bibi Ka Maqbara in Aurangabad, a tomb for Rabia-ud-Daurani, was built by his oldest son Azam Shah at Aurangzeb's command. Its design is clearly inspired by the Taj Mahal. Aurangzeb also provided and repaired city structures like forts (for example, a wall around Aurangabad), bridges, caravanserais (roadside inns), and gardens.

Aurangzeb was more involved in repairing and maintaining existing buildings. The most important of these were mosques, both Mughal and older ones, which he repaired more than any emperor before him. He supported the dargahs (shrines) of Sufi saints and worked to maintain royal tombs.

-

The 17th-century Badshahi Masjid built by Aurangzeb in Lahore.

-

Tomb of Sufi saint, Syed Abdul Rahim Shah Bukhari constructed by Aurangzeb.

Textiles

The textile industry in the Mughal Empire grew very strong during Aurangzeb's rule. François Bernier, a French doctor who worked for the Mughal Emperor, noted this. He wrote about how Karkanahs, or workshops for artisans, especially in textiles, thrived. These workshops employed hundreds of embroiderers. He also described the making of silk, fine brocade, and other delicate muslins used for turbans and robes.

He explained different techniques for making complex textiles like Himru (Persian for "brocade"), Paithani (same pattern on both sides), and Mushru (satin weave). He also noted that Kalamkari, where fabrics are painted or block-printed, came from Persia. Francois Bernier gave some of the first detailed descriptions of the designs and soft texture of Pashmina shawls, also called Kani. These shawls were highly valued by the Mughals for their warmth and comfort. These textiles and shawls eventually made their way to France and England.

Foreign Relations

Aurangzeb sent diplomatic missions to Mecca in 1659 and 1662, with money and gifts for the Sharif. He also sent aid in 1666 and 1672 to be given out in Mecca and Medina. However, by 1694, Aurangzeb's enthusiasm for the Sharifs of Mecca lessened because he felt they were greedy and kept the money for themselves, instead of giving it to the needy.

Relations with the Uzbeks

Subhan Quli Khan, the Uzbek ruler of Balkh, was the first to recognize Aurangzeb as emperor in 1658. He asked for a general alliance. He had worked with Aurangzeb since 1647, when Aurangzeb was the governor of Balkh.

Relations with the Safavid Dynasty

Aurangzeb welcomed the ambassadors from Abbas II of Persia in 1660 and sent them back with gifts. However, relations between the Mughal Empire and the Safavid dynasty were tense because the Persians attacked the Mughal army near Kandahar. Aurangzeb prepared his armies for a counterattack, but Abbas II's death in 1666 ended all fighting. Aurangzeb's rebellious son, Sultan Muhammad Akbar, found safety with Suleiman I of Persia, who refused to help him in any military actions against Aurangzeb.

Relations with the French

In 1667, ambassadors from the French East India Company presented a letter from Louis XIV of France. The letter asked for protection for French merchants from rebels in the Deccan. In response, Aurangzeb issued an official order (firman) allowing the French to open a trading post in Surat.

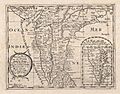

-

French map of the Deccan.

Relations with the Sultanate of Maldives

In the 1660s, the Sultan of the Maldives, Ibrahim Iskandar I, asked for help from Aurangzeb's representative. The Sultan wanted support to possibly expel Dutch and English trading ships, as he was worried about their impact on the Maldives' economy. However, Aurangzeb did not have a strong navy and was not interested in helping Ibrahim in a potential war with the Dutch or English, so the request was not fulfilled.

Relations with the Ottoman Empire

Like his father, Aurangzeb did not accept the Ottoman claim to be the leader of all Muslims (caliphate). He often supported the Ottoman Empire's enemies. He welcomed two rebellious governors from Basra and gave them high positions in his service. Sultan Suleiman II's friendly gestures were ignored by Aurangzeb. The Sultan urged Aurangzeb to wage holy war against Christians.

Relations with the English and the Anglo-Mughal War

In 1686, the East India Company tried to get an official order (firman) that would give them regular trading rights across the Mughal Empire, but they failed. So, they started the Anglo-Mughal War. This war ended badly for the English. In 1689, Aurangzeb sent a large fleet that blockaded Bombay. The ships were commanded by Sidi Yaqub and manned by Indians. In 1690, realizing they were losing the war, the Company sent envoys to Aurangzeb's camp to ask for forgiveness. They bowed before the emperor, agreed to pay a large amount of money, and promised not to do such things again.

In September 1695, English pirate Henry Every carried out one of the most profitable pirate raids in history. He captured a large Mughal trading convoy near Surat. The Indian ships were returning from their annual pilgrimage to Mecca. The pirate captured the Ganj-i-Sawai, said to be the largest ship in the Muslim fleet, and its escorts. When news reached the mainland, an angry Aurangzeb almost ordered an armed attack on the English-controlled city of Bombay. However, he finally agreed to a compromise after the Company promised to pay financial compensation. Meanwhile, Aurangzeb shut down four of the English East India Company's trading posts, imprisoned the workers and captains, and threatened to stop all English trade in India until Every was caught.

In 1702, Aurangzeb sent Daud Khan Panni, the Mughal governor of the Carnatic region, to surround and blockade Fort St. George for over three months. The governor of the fort, Thomas Pitt, was told by the East India Company to ask for peace.

Relations with the Ethiopian Empire

Ethiopian Emperor Fasilides sent ambassadors to India in 1664–65 to congratulate Aurangzeb on becoming the Mughal Emperor.

Relations with Tibetans, Uyghurs, and Dzungars

After 1679, the Tibetans invaded Ladakh, which was under Mughal influence. Aurangzeb helped Ladakh in 1683, but his troops retreated before Dzungar reinforcements arrived to help the Tibetans.

Relations with the Russian Czardom

Russian Czar Peter the Great asked Aurangzeb to start trade relations between Russia and the Mughal Empire in the late 17th century. In 1696, Aurangzeb welcomed his envoy, Semyon Malenkiy, and allowed him to trade freely. After six years in India, Russian merchants returned to Moscow with valuable Indian goods.

Administrative Changes

Tribute and Revenue

Aurangzeb received tribute from all over the Indian subcontinent. He used this wealth to build bases and forts in India, especially in the Carnatic, Deccan, Bengal, and Lahore.

Aurangzeb's treasury collected a record £100 million in annual income from various sources like taxes, customs, and land revenue from 24 provinces. He had an annual income of $450 million, which was more than ten times that of Louis XIV of France at the same time.

Coins

Aurangzeb believed that verses from the Quran should not be stamped on coins, as they were often touched by people's hands and feet.

Rebellions During Aurangzeb's Reign

Different groups in northern and western India, like the Marathas, Rajputs, Hindu Jats, Pashtuns, and Sikhs, gained military experience during Mughal rule.

- In 1669, the Hindu Jat farmers of Bharatpur rebelled but were defeated.

- In 1659, Shivaji launched a surprise attack on the Mughal Viceroy Shaista Khan. Shivaji and his forces attacked the Deccan, Janjira, and Surat, trying to take control of large areas. In 1689, Aurangzeb's armies captured Shivaji's son Sambhaji and executed him. But the Marathas continued to fight.

- In 1679, the Rathore clan rebelled when Aurangzeb did not allow the young Rathore prince to become king. This caused unrest among Hindu Rajput rulers and led to many rebellions.

- In 1672, the Satnami, a religious group, took over the administration of Narnaul, but Aurangzeb personally intervened and crushed them.

- In 1671, the battle of Saraighat was fought against the Ahom Kingdom in the east. The Mughals were defeated.

- Maharaja Chhatrasal, a warrior from the Bundela Rajput clan, fought against Aurangzeb and established his own kingdom in Bundelkhand.

Jat Rebellion

In 1669, Hindu Jats started a rebellion. This is believed to have been caused by the return of the jizya tax and the destruction of Hindu temples in Mathura. The Jats were led by Gokula. By 1670, 20,000 Jat rebels were defeated. Gokula was caught and executed.

However, the Jats rebelled again. Raja Ram Jat, to get revenge for Gokula's death, looted Akbar's tomb. He took gold, silver, and carpets, opened Akbar's grave, and burned his bones. The Jats also damaged the minarets at the entrance to Akbar's Tomb and melted down two silver doors from the Taj Mahal. Aurangzeb sent Mohammad Bidar Bakht to crush the Jat rebellion. On 4 July 1688, Raja Ram Jat was captured and executed.

After Aurangzeb's death, the Jats, led by Badan Singh, later created their own independent state of Bharatpur.

Mughal–Maratha Wars

In 1657, while Aurangzeb attacked Golconda and Bijapur, the Hindu Maratha warrior, Shivaji, used surprise attacks to take control of three forts. With these wins, Shivaji became the leader of many independent Maratha groups. The Marathas bothered the Adil Shahis, gaining weapons, forts, and land. Shivaji's small army survived an attack, and Shivaji personally killed the Adil Shahi general. After this, the Marathas became a strong military force, taking more and more Adil Shahi lands. Shivaji then worked to weaken Mughal power in the region.

In 1659, Aurangzeb sent his trusted general, Shaista Khan, to take back forts lost to the Maratha rebels. Shaista Khan entered Maratha territory and settled in Pune. But in a daring raid on the governor's palace, led by Shivaji himself, the Marathas killed Shaista Khan's son. Shaista Khan survived and was later made administrator of Bengal.

Aurangzeb then sent general Raja Jai Singh to defeat the Marathas. Jai Singh surrounded the fort of Purandar and fought off all attempts to help it. Seeing defeat, Shivaji agreed to terms. Jai Singh convinced Shivaji to visit Aurangzeb in Agra, promising him safety. Their meeting at the Mughal court did not go well. Shivaji felt disrespected and insulted Aurangzeb by refusing to serve the empire. For this, he was held captive but managed to escape.

Shivaji returned to the Deccan and crowned himself Chhatrapati (ruler) of the Maratha Kingdom in 1674. Shivaji expanded Maratha control until his death in 1680. His son, Sambhaji, succeeded him. Mughal efforts to control the Deccan continued to fail.

In 1689, Aurangzeb's forces captured and executed Sambhaji. His successors, Rajaram and later his widow Tarabai, and their Maratha forces fought many battles against the Mughal Empire. Land changed hands many times during the years of fighting (1689–1707). Since there was no single central authority among the Marathas, Aurangzeb had to fight for every bit of land, which cost many lives and much money. Even as Aurangzeb pushed west into Maratha territory, the Marathas expanded east into Mughal lands. The Marathas also expanded further south into Southern India. Aurangzeb fought continuous wars in the Deccan for over two decades without a clear end. He lost about a fifth of his army fighting these rebellions. He traveled a long distance to the Deccan to conquer the Marathas and eventually died there at the age of 88, still fighting.

Aurangzeb's change from traditional warfare to fighting rebels in the Deccan changed how the Mughals thought about military strategy. There were conflicts between Marathas and Mughals in Pune, Jinji, Malwa, and Vadodara. The Mughal port city of Surat was attacked twice by the Marathas during Aurangzeb's rule and was left in ruins.

Some estimates suggest that about 2.5 million of Aurangzeb's soldiers died during the Mughal–Maratha Wars. Also, 2 million civilians in war-torn areas died due to drought, plague, and famine.

Ahom Campaign

While Aurangzeb and his brother Shah Shuja were fighting each other, the Hindu rulers of Kuch Behar and Assam took advantage of the Mughal Empire's problems and invaded imperial lands. For three years, they were not attacked. But in 1660, Mir Jumla II, the viceroy of Bengal, was ordered to take back the lost territories.

The Mughals set out in November 1661. Within weeks, they took the capital of Kuch Behar and added it to their empire. Leaving a small group of soldiers there, the Mughal army began to retake their lands in Assam. Mir Jumla II advanced on Garhgaon, the capital of the Ahom kingdom, and reached it on 17 March 1662. The ruler, Raja Sutamla, had fled before he arrived. The Mughals captured many elephants, money, ships, and stores of rice.

On his way back to Dacca in March 1663, Mir Jumla II died. Fights continued between the Mughals and Ahoms after Chakradhwaj Singha became ruler. He refused to pay more money to the Mughals. The Mughals faced great difficulties during these wars. Although the Mughals were defeated by two Ahom armies in 1667, they continued to hold their eastern territories even after the battle of Saraighat in 1671.

The battle of Saraighat was fought in 1671 between the Mughal empire and the Ahom Kingdom. The Ahom Army, though weaker, defeated the Mughal Army by using the land cleverly, smart negotiations to gain time, guerrilla tactics, and by exploiting the Mughal navy's weakness.

The battle of Saraighat was the last major attempt by the Mughals to expand their empire into Assam. Although the Mughals briefly regained Guwahati, the Ahoms took control back in the battle of Itakhuli in 1682 and kept it until the end of their rule.

Satnami Opposition

In May 1672, the Satnami religious group started a large revolt in the farming areas of the Mughal Empire. The Satnamis were known to shave their heads and eyebrows. They had temples in many parts of Northern India. They began a large rebellion southwest of Delhi.

The Satnamis believed they could not be harmed by Mughal bullets. They started marching towards Delhi and defeated small Mughal infantry units.

Aurangzeb responded by gathering a Mughal army of 10,000 troops and artillery. He sent parts of his personal Mughal imperial guards to help. To boost Mughal morale, Aurangzeb wrote Islamic prayers and made amulets. This rebellion had a serious impact on the Punjab region.

Sikh Opposition

The ninth Sikh Guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur, like the Gurus before him, was against forcing people to change their religion. When Kashmiri Pandits asked him for help to keep their faith, Guru Tegh Bahadur sent a message to the emperor. He said that if Aurangzeb could convert him to Islam, then all Hindus would become Muslim. In response, Aurangzeb ordered the Guru's arrest. When he refused to convert, he was executed in 1675.

In response, Guru Tegh Bahadur's son and successor, Guru Gobind Singh, made his followers more military-focused. He established the Khalsa in 1699, eight years before Aurangzeb's death. In 1705, Guru Gobind Singh sent a letter called Zafarnamah. This letter accused Aurangzeb of cruelty and betraying Islam. The letter caused Aurangzeb much distress. Guru Gobind Singh's creation of the Khalsa led to the formation of the Sikh Confederacy and later the Sikh Empire.

Pashtun Opposition

The Pashtun revolt in 1672, led by the poet Khushal Khan Khattak of Kabul, began when soldiers under the Mughal Governor Amir Khan reportedly attacked women of the Pashtun tribes. The Safi tribes fought back against the soldiers. This attack led to a larger revolt by most of the tribes. Amir Khan led a large Mughal army to the Khyber Pass, where the army was surrounded by tribesmen and defeated. Only four men, including the Governor, managed to escape.

Aurangzeb's actions in the Pashtun areas were described by Khushal Khan Khattak as "Black is the Mughal's heart towards all of us Pathans." Aurangzeb used a "scorched earth" policy, sending soldiers who massacred, looted, and burned many villages. Aurangzeb also used bribery to turn Pashtun tribes against each other. This was meant to stop a united Pashtun challenge to Mughal authority. This left a lasting feeling of mistrust among the tribes.

After that, the revolt spread, and Mughal authority almost completely collapsed in the Pashtun region. The closing of the important Attock-Kabul trade route was especially damaging. By 1674, the situation was so bad that Aurangzeb camped at Attock to take personal charge. By using diplomacy, bribery, and force, the Mughals eventually divided the rebels and partly stopped the revolt. However, they never fully controlled the areas outside the main trade route.

Death and Legacy

By 1689, the Mughal Empire had grown to 4 million square kilometers, with an estimated population of over 158 million people. But this power did not last long. Historians say that the peak of the empire's power under Aurangzeb also marked the beginning of its decline.

Aurangzeb built a small marble mosque called the Moti Masjid (Pearl Mosque) in the Red Fort complex in Delhi. However, his constant wars, especially with the Marathas, pushed his empire close to bankruptcy.

Even when he was sick and dying, Aurangzeb made sure people knew he was alive. If they thought he had died, another war for the throne would likely begin. He died at his military camp near Ahmednagar on 3 March 1707, at the age of 88. He had only 300 rupees with him, which he asked to be given to charity. He also requested a simple funeral. His humble open-air grave in Khuldabad, Aurangabad, Maharashtra, shows his strong Islamic faith. It is in the courtyard of the shrine of the Sufi saint Shaikh Burhan-u'd-din Gharib.

After his death, a series of weak emperors, wars for the throne, and power grabs by noblemen led to the Mughal Empire's decline. Although Aurangzeb did not name a successor, he told his three sons to divide the empire among themselves. His sons could not agree and fought each other in a war of succession. Aurangzeb's immediate successor was his third son Azam Shah, who was defeated and killed in June 1707 by the army of Bahadur Shah I, Aurangzeb's second son. Because of Aurangzeb's over-expansion and Bahadur Shah's weak leadership, the empire began a period of decline. Soon after Bahadur Shah became emperor, the Maratha Empire grew stronger and launched successful invasions of Mughal territory, taking power from the weak emperor. Within decades of Aurangzeb's death, the Mughal Emperor had little power beyond the walls of Delhi.

Assessments and Legacy

Aurangzeb's rule has been both praised and criticized. He is often described as one of the most debated rulers in Indian history. During his lifetime, his victories in the south expanded the Mughal Empire to 4 million square kilometers, ruling over an estimated 158 million people. His critics argue that his harshness and religious strictness made him unsuitable to rule an empire with many different people. Some critics say that his persecution of Shias, Sufis, and non-Muslims, his reintroduction of the jizya tax, higher taxes on Hindus, executions, and destruction of temples led to many rebellions.

There are many different views on Aurangzeb's life and rule. Some argue that his policies abandoned the previous emperors' ideas of religious tolerance. They point to his introduction of the jizya tax, destruction of Hindu temples, and the executions of his brother Dara Shikoh, King Sambhaji, and Sikh Guru Tegh Bahadur. At the same time, some historians question how accurate these criticisms are. They argue that the destruction of temples has been exaggerated. They note that he built more temples than he destroyed, paid for their upkeep, and employed many more Hindus in his government than his predecessors.

In Pakistan, Aurangzeb is often seen as a hero who fought and expanded the Islamic empire. He is imagined as a true believer who removed bad practices from religion and the court. Some Pakistani scholars say that Aurangzeb is included among premodern Muslim heroes, especially for his military strength, personal faith, and willingness to follow Islamic morals in government.

Muhammad Iqbal, considered the spiritual founder of Pakistan, praised Aurangzeb for his fight against Akbar's Din-i Ilahi (a new religion) and idol worship. Iqbal believed that Aurangzeb's life was the starting point of Muslim nationality in India.

This image of Aurangzeb is not only found in Pakistan. Historian Audrey Truschke notes that BJP and other Hindu nationalists see him as a Muslim extremist. Nehru claimed that Aurangzeb acted "more as a Moslem than an Indian ruler" because he reversed the cultural and religious mixing of earlier Mughal emperors.

Full Title

The name Aurangzeb means 'Ornament of the Throne'. His chosen title Alamgir means 'Conqueror of the World'.

Aurangzeb's full imperial title was:

Al-Sultan al-Azam wal Khaqan al-Mukarram Hazrat Abul Muzaffar Muhy-ud-Din Muhammad Aurangzeb Bahadur Alamgir I, Badshah Ghazi, Shahanshah-e-Sultanat-ul-Hindiya Wal Mughaliya.

Aurangzeb was also given other titles like Caliph of The Merciful, Monarch of Islam, and Living Custodian of God.

Literature

Aurangzeb has been featured in these books:

- 1675 – Aureng-zebe, a play by John Dryden, performed in London during the Emperor's lifetime.

- 1970 – Shahenshah (Marathi: शहेनशहा), a Marathi fictional biography by N S Inamdar; translated into English in 2017 as Shahenshah – The Life of Aurangzeb.

- 2017 – 1636: Mission to the Mughals, by Eric Flint and Griffin Barber.

- 2018 – Aurangzeb: The Man and the Myth, by Audrey Truschke.

See Also

In Spanish: Aurangzeb para niños

In Spanish: Aurangzeb para niños

- Flags of the Mughal Empire

- Mughal architecture

- Mughal weapons

- List of largest empires

|

Tables

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |