Turkish literature facts for kids

Turkish literature includes stories, poems, and other writings in the Turkish language. The older form of Turkish, called Ottoman Turkish, was greatly shaped by Persian and Arabic literature. It used the Ottoman Turkish alphabet.

The history of all Turkic literature goes back almost 1,300 years. The oldest writings in Turkic are the Orhon inscriptions. These were found in Mongolia and are from the 7th century. Later, between the 9th and 11th centuries, nomadic Turkic peoples in Central Asia created many oral epics. Famous examples include the Book of Dede Korkut from the Oghuz Turks (who are ancestors of today's Turkish people) and the Epic of Manas from the Kyrgyz people.

After the Seljuks won the Battle of Manzikert in the late 11th century, the Oghuz Turks started settling in Anatolia. Along with their oral stories, they began a written literary tradition. This new style was heavily influenced by Arabic and Persian literature in its themes and forms. For the next 900 years, until the Ottoman Empire ended in 1922, the oral and written traditions stayed mostly separate. When the Republic of Turkey was founded in 1923, these two traditions finally came together.

Contents

History of Turkish Literature

The earliest known Turkic poetry is from around the 6th century AD. It was written in the Uyghur language. Some of these early poems by Uyghur Turkic writers are only known through Chinese translations. In the past, early Turkic poems were sung as part of community life and fun. For example, in the old shamanistic and animistic cultures of pre-Islamic Turkic peoples, poems were performed at religious events. These included ceremonies before a hunt (sığır) and feasts after a hunt (şölen). Poetry was also sung during sad times. Special poems called sagu were recited at funerals (yuğ) and other events to remember the dead.

Of the long epic poems, only the Oğuzname has survived completely. The Book of Dede Korkut might have started as poetry in the 10th century. But it stayed an oral story until the 15th century. Earlier written works like Kutadgu Bilig and Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk are from the second half of the 11th century. They are some of the first known examples of Turkish literature.

One very important person in early Turkish literature was the 13th-century Sufi poet Yunus Emre. The best time for Ottoman literature was from the 15th to the 18th century. This period mostly featured divan poetry. But it also included some prose works, like the 10-volume Seyahatnâme (Book of Travels) by Evliya Çelebi.

Different Periods of Turkish Literature

Scholars have different ideas about how to divide the history of Turkic literature into periods. One idea splits it into early literature (8th to 19th century) and modern literature (19th to 21st century). Other ways of grouping it divide the literature into three periods: pre-Islamic, Islamic, and modern; or pre-Ottoman, Ottoman, and modern.

A more detailed approach suggests five stages. These include a pre-Islamic period (until the 11th century) and a pre-Ottoman Islamic period (between the 11th and 13th centuries). This five-stage approach also divides modern literature into a transition period (from the 1850s to the 1920s) and a modern period that continues to today.

The Two Main Styles of Turkish Literature

For most of its history, Turkish literature has been clearly split into two different styles. These styles did not influence each other much until the 19th century. The first style is Turkish folk literature, and the second is Turkish written literature.

The main difference between these two styles was the kind of language they used. The folk tradition was mostly oral. It was passed down by minstrels (traveling singers and storytellers). It stayed free from the influence of Persian and Arabic literature and their languages. In folk poetry, which was the most common type, this led to two main things:

- Folk poetry used syllabic verse. This means the number of syllables in each line was important.

- The main part of folk poetry was the quatrain (Turkish: dörtlük), which is a four-line stanza. This was different from the couplets (Turkish: beyit), or two-line stanzas, used more in written poetry.

Also, Turkish folk poetry was always closely linked to song. Most of these poems were made to be sung. So, they became a big part of Turkish folk music.

In contrast, Turkish written literature, before the Republic of Turkey was founded in 1923, was very open to Persian and Arabic influences. This started as early as the Seljuk period (late 11th to early 14th centuries). During this time, official business was done in Persian, not Turkish. Poets like Dehhanî, who worked for the 13th-century sultan Ala ad-Din Kay Qubadh I, wrote in a language that had a lot of Persian words.

When the Ottoman Empire began in the early 14th century, it continued this tradition. The main forms of poetry were taken directly from Persian literature (like the gazel and the mesnevî). Or they came from Arabic through Persian (like the kasîde). However, using these poetic forms completely led to two important results:

- The poetic meters (Turkish: aruz) from Persian poetry were adopted.

- Many Persian and Arabic words were brought into the Turkish language. Turkish words often did not fit well with the Persian poetic meters.

Because of these choices, the Ottoman Turkish language was born. It was very different from spoken Turkish. This style of writing, influenced by Persian and Arabic, became known as "Divan literature" (Turkish: divan edebiyatı). Dîvân was the Ottoman Turkish word for a poet's collected works.

Just as Turkish folk poetry was tied to Turkish folk music, Ottoman Divan poetry also became strongly connected to Turkish classical music. Poems by Divan poets were often used as song lyrics.

Turkish Folk Literature

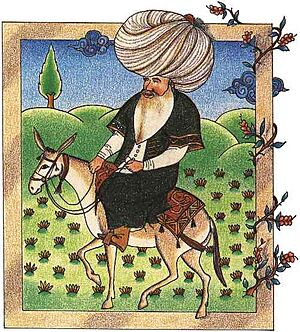

Turkish folk literature is an oral tradition. Its style comes from the nomadic traditions of Central Asia. However, its themes show the challenges of people who have settled down and left their nomadic life. One example is the series of folktales about Keloğlan. He is a young boy who struggles to find a wife, help his mother keep their home, and deal with neighbors. Another example is the mysterious figure of Nasreddin. He is a trickster who often plays jokes on his neighbors.

Nasreddin also shows a big change that happened as Turkish people moved from being nomads to settling in Anatolia. Nasreddin is a Muslim Imam (a religious leader). The Turkic peoples first became Islamized around the 9th or 10th century. This is clear from the Islamic influence in the 11th-century Kutadgu Bilig ("Wisdom of Royal Glory") by Yusuf Has Hajib. From then on, Islam had a huge impact on Turkish society and literature. This was especially true for the mystical Sufi and Shi'a types of Islam.

For example, Sufi influence can be seen in the stories about Nasreddin. It is also clear in the works of Yunus Emre. He was a very important poet in Turkish literature who lived in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. The Shi'a influence is strong in the tradition of the aşıks, or ozans. These are like medieval European minstrels. They have traditionally been connected to the Alevi faith, which is a Turkish form of Shi'a Islam. However, it's hard to separate Sufi and Shi'a influences in Turkish culture. For instance, some think Yunus Emre was an Alevi. And the whole Turkish aşık/ozan tradition is full of ideas from the Bektashi Sufi order, which mixes Shi'a and Sufi ideas. The word aşık (meaning "lover") is actually the term for first-level members of the Bektashi order.

Because Turkish folk literature has continued from about the 10th or 11th century until today, it's best to look at it by its types of stories. There are three main types: epic, folk poetry, and folklore.

The Epic Tradition

The Turkish epic comes from the Central Asian epic tradition. This tradition gave us the Book of Dede Korkut. This book is written in Azerbaijani, which is similar to modern Turkish. It grew from the oral stories of the Oghuz Turks. These Turks moved to western Asia and eastern Europe starting in the 9th century. The Book of Dede Korkut continued as an oral story among the Oghuz Turks after they settled in Anatolia. Alpamysh is an older epic. It is still found in the literature of various Turkic peoples in Central Asia, and it is also important in Anatolian tradition.

The Book of Dede Korkut was the main epic story for Azerbaijani-Turkish people in the Caucasus and Anatolia for centuries. At the same time, there was the Epic of Köroğlu. This story is about Rüşen Ali ("Köroğlu," or "son of the blind man") getting revenge for his father being blinded. The origins of this epic are a bit mysterious. Many believe it started in Anatolia between the 15th and 17th centuries. But other evidence suggests it's almost as old as the Book of Dede Korkut, from around the 11th century. It's also confusing because Köroğlu is the name of a poet from the aşık/ozan tradition.

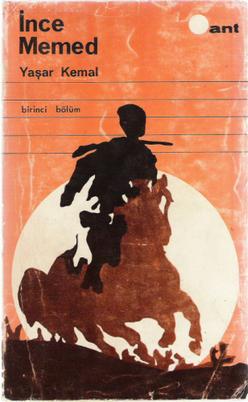

In modern Turkish literature, you can see the epic tradition in the Epic of Shaykh Bedreddin (Şeyh Bedreddin Destanı). This was published in 1936 by the poet Nâzım Hikmet Ran (1901–1963). This long poem is about an Anatolian shaykh's rebellion against the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed I. It is a modern epic, but it uses the same spirit of independence found in the Epic of Köroğlu. Many works by the 20th-century novelist Yaşar Kemal (1923–2015), like his 1955 novel Memed, My Hawk (İnce Memed), can be seen as modern prose epics that continue this long tradition.

Folk Poetry

As mentioned, Turkish folk poetry was greatly influenced by Islamic Sufi and Shi'a traditions. Also, the most important part of Turkish folk poetry has always been song. This is clear from the aşık/ozan tradition that still exists. The development of Turkish folk poetry began in the 13th century with writers like Yunus Emre, Sultan Veled, and Şeyyâd Hamza. It got a big boost on May 13, 1277, when Karamanoğlu Mehmet Bey declared Turkish the official state language of the powerful Karamanid state in Anatolia. After this, many of the greatest poets of this tradition came from that region.

Generally, there are two main styles (or schools) of Turkish folk poetry:

- The aşık/ozan tradition: This was mostly a non-religious tradition, though it was influenced by religion.

- The religious tradition: This came from the meeting places (tekkes) of Sufi religious groups and Shi'a groups.

Much of the poetry and songs from the aşık/ozan tradition were passed down orally until the 19th century. So, many of the authors are unknown. However, some famous aşıks from before that time are known, and their works have survived. These include Köroğlu (16th century), Karacaoğlan (1606?–1689?), who might be the most famous aşık before the 19th century, and Dadaloğlu (1785?–1868?), who was one of the last great aşıks before the tradition started to fade in the late 19th century.

The aşıks were like minstrels who traveled through Anatolia. They performed their songs on the bağlama. This is a stringed instrument similar to a mandolin. Its paired strings are thought to have a special religious meaning in Alevi/Bektashi culture. Even though the aşık/ozan tradition declined in the 19th century, it came back strong in the 20th century. This was thanks to great figures like Aşık Veysel Şatıroğlu (1894–1973), Aşık Mahzuni Şerif (1938–2002), and Neşet Ertaş (1938–2012).

The religious folk tradition of tekke literature was similar to the aşık/ozan tradition. The poems were usually meant to be sung, often in religious gatherings. This makes them a bit like Western hymns (Turkish ilahi). However, one big difference was that the poems of the tekke tradition were written down from the very beginning. This was because they were created by respected religious figures in the literate environment of the tekke. In contrast, most people in the aşık/ozan tradition could not read or write.

Important figures in the tekke literature tradition include: Yunus Emre (1240?–1320?), who is one of the most important figures in all of Turkish literature; Süleyman Çelebi (?–1422), who wrote a very popular long poem called Vesîletü'n-Necât ("The Means of Salvation," also known as the Mevlid), about the birth of the Islamic prophet Muhammad; Kaygusuz Abdal (1397–?), who is seen as the founder of Alevi/Bektashi literature; and Pir Sultan Abdal (?–1560), whom many consider the best of that literature.

Folklore

The tradition of folklore in the Turkish language, including folktales, jokes, and legends, is very rich. Perhaps the most popular figure is Nasreddin (known as Nasreddin Hoca, or "teacher Nasreddin," in Turkish). He is the main character in thousands of funny stories. He often seems a bit silly to others, but he actually has his own special wisdom:

One day, Nasreddin's neighbor asked him, "Hoca, do you have any forty-year-old vinegar?"—"Yes, I do," answered Nasreddin.—"Can I have some?" asked the neighbor. "I need some to make an ointment with."—"No, you can't have any," answered Nasreddin. "If I gave my forty-year-old vinegar to whoever wanted some, I wouldn't have had it for forty years, would I?"

Similar to Nasreddin's jokes are the Bektashi jokes. These jokes come from a similar religious background. In them, members of the Bektashi religious order, shown through a character named Bektaşi, have an unusual and different kind of wisdom. This wisdom often questions the values of Islam and society.

Another popular part of Turkish folklore is the shadow theater featuring two characters: Karagöz and Hacivat. These characters represent common types of people. Karagöz, from a small village, is a bit of a country bumpkin. Hacivat is a more refined city person. A popular legend says that these two characters are based on real people. They supposedly worked for either Osman I, who founded the Ottoman Dynasty, or his successor Orhan I. They were building a palace or mosque in Bursa in the early 14th century. The two workers supposedly spent a lot of time entertaining others. They were so funny that they slowed down the work on the palace, and then they were beheaded.

Ottoman Written Literature

The two main types of Ottoman written literature were poetry and prose (regular writing, not poetry). Poetry, especially Divan poetry, was much more important. Also, until the 19th century, Ottoman prose did not include any fiction. There were no novels, short stories, or romances like in Europe. (Though similar types of stories did exist in Turkish folk tradition and Divan poetry).

Divan Poetry

Ottoman Divan poetry was a very formal and symbolic art form. It got many of its symbols from Persian poetry, which inspired it. Divan poetry, like Turkish folk poetry, was heavily influenced by Sufi ideas.

Even though Turkish poets were inspired by classical Persian poetry, it's not fair to say they just copied it. All poets of Islamic literature shared a similar vocabulary, techniques, and themes, mostly based on Islamic sources.

While it's hard to define exact styles and periods in Divan poetry, some very different styles are clear. They can be seen in the works of certain poets:

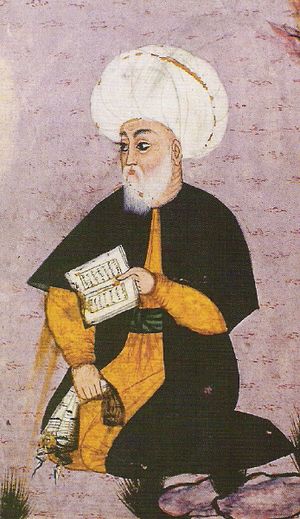

- Fuzûlî (1483?–1556): A unique poet who wrote equally well in Azerbaijani, Persian, and Arabic. He became important in both Persian and Divan poetry.

- Bâkî (1526–1600): A poet with great speaking power and language skill. His use of the traditional forms of Divan poetry shows the style of poetry during the time of Süleyman the Magnificent.

- Nef‘î (1570?–1635): Considered the master of the kasîde (a type of praise poem). He was also known for his harsh, satirical poems, which led to his execution.

- Nâbî (1642–1712): A poet who wrote many poems about society, criticizing the slow period of Ottoman history.

- Nedîm (1681?–1730): A revolutionary poet during the Tulip Era of Ottoman history. He brought simpler, more popular elements into the rather complex language of Divan poetry.

- Şeyh Gâlib (1757–1799): A poet from the Mevlevî Sufi order. His work is seen as the peak of the very complex "Indian style" (سبك هندى sebk-i hindî).

Most Divan poetry was lyric in nature. This means it expressed feelings. It was either gazels (the most common type) or kasîdes. However, there were other common types, especially the mesnevî. This was a kind of verse romance and a type of narrative poetry (storytelling in verse). The two most famous examples are Leylî vü Mecnun by Fuzûlî and Hüsn ü Aşk ("Beauty and Love") by Şeyh Gâlib.

Early Ottoman Prose

Until the 19th century, Ottoman prose (regular writing) did not develop as much as Divan poetry. A big reason for this was that much prose had to follow the rules of sec' (سجع, also called seci), or rhymed prose. This style, from Arabic saj', required that almost every adjective and noun in a sentence had to rhyme.

However, there was still a tradition of prose writing. This tradition was only for nonfictional works. Fiction was limited to narrative poetry. Several nonfictional prose types developed:

- The târih (تاريخ), or history: Many famous writers worked in this area, including the 15th-century historian Aşıkpaşazâde and the 17th-century historians Kâtib Çelebi and Naîmâ.

- The seyâhatnâme (سياحت نامه), or travelogue: The best example is the 17th-century Seyahâtnâme by Evliya Çelebi.

- The sefâretnâme (سفارت نامه): A related type of writing about the journeys and experiences of an Ottoman ambassador. The 1718–1720 Paris Sefâretnâme by Yirmisekiz Mehmed Çelebi, ambassador to the court of Louis XV of France, is a great example.

- The siyâsetnâme (سياست نامه): A political book that described how the state worked and offered advice to rulers. An early Seljuk example is the 11th-century Siyāsatnāma, written in Persian by Nizam al-Mulk.

The 19th Century and Western Influence

By the early 19th century, the Ottoman Empire was struggling. Efforts to fix this started during the rule of Sultan Selim III (1789–1807). But they were stopped by the powerful Janissary army. So, real reforms (Ottoman Turkish: تنظيمات tanzîmât) only began after Sultan Mahmud II got rid of the Janissary corps in 1826.

These reforms finally happened during the Tanzimat period (1839–1876). Much of the Ottoman system was reorganized, mostly following French ideas. The Tanzimat reforms aimed to both modernize the empire and prevent other countries from interfering.

Along with changes to the Ottoman system, big changes also happened in literature. These literary changes can be put into two main groups:

- Changes to the language of Ottoman written literature.

- The introduction of new types of writing into Ottoman literature.

The language reforms happened because reformers thought the Ottoman Turkish language had lost its way. It had become more separate from its original Turkish roots. Writers were using more and more words and even grammar rules from Persian and Arabic, instead of Turkish. Meanwhile, the Turkish folk literature tradition in Anatolia, away from the capital Constantinople, was seen as an ideal. So, many reformers called for written literature to move away from the Divan tradition and towards the folk tradition. This call for change can be seen in a famous statement by the poet and reformer Ziya Pasha (1829–1880):

Our language is not Ottoman; it is Turkish. What makes up our poetic canon is not gazels and kasîdes, but rather kayabaşıs, üçlemes, and çöğürs', which some of our poets dislike, thinking them crude. But just let those with the ability exert the effort on this road [of change], and what powerful personalities will soon be born!

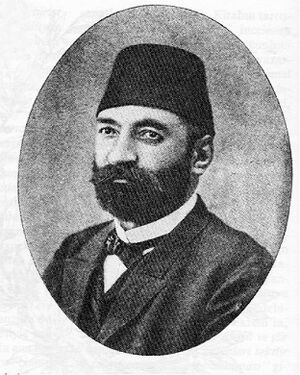

At the same time, new types of literature were brought into Ottoman literature, mainly the novel and the short story. This started in 1861, with the translation of François Fénelon's 1699 novel Les aventures de Télémaque into Ottoman Turkish by Hüseyin Avni Pasha for Sultan Abdülaziz. What is widely considered the first Turkish novel, Taaşuk-u Tal'at ve Fitnat ("Tal'at and Fitnat in Love") by Şemsettin Sami (1850–1904), was published just ten years later, in 1872. However, there were actually five other earlier or similar works of fiction that were different from older prose traditions and were close to novel form. Among these was Muhayyelât by Ali Aziz Efendi. Another, Akabi Hikâyesi ("Akabi's Story") from 1851, written by the Armenian Vartan Pasha (Hovsep Vartanian) using the Armenian script for an Armenian audience, was "the first true modern novel written and published in Turkey," according to Andreas Tietze. Bringing these new types of writing into Turkish literature was part of a trend towards Westernization that continues in Turkey today.

Because of close ties with France, strengthened during the Crimean War (1854–1856), French literature became the main Western influence on Turkish literature in the late 19th century. As a result, many literary movements popular in France also appeared in the Ottoman Empire. For example, in the developing Ottoman prose, the influence of Romanticism can be seen during the Tanzimat period. Later, the Realist and Naturalist movements appeared. In poetry, the influence of the Symbolist and Parnassian movements became very important.

Many writers during the Tanzimat period wrote in several different styles at once. For example, the poet Namık Kemal (1840–1888) also wrote the important 1876 novel İntibâh ("Awakening"). The journalist İbrahim Şinasi (1826–1871) is known for writing the first modern Turkish play in 1860, the one-act comedy "Şair Evlenmesi" ("The Poet's Marriage"). Similarly, the novelist Ahmed Midhat Efendi (1844–1912) wrote important novels in each of the main movements: Romanticism (Hasan Mellâh yâhud Sırr İçinde Esrâr, 1873; "Hasan the Sailor, or The Mystery Within the Mystery"), Realism (Henüz On Yedi Yaşında, 1881; "Just Seventeen Years Old"), and Naturalism (Müşâhedât, 1891; "Observations"). This variety was partly because Tanzimat writers wanted to spread as much of the new literature as possible. They hoped it would help revitalize Ottoman society.

Early 20th-Century Turkish Literature

Most of the foundations of modern Turkish literature were laid between 1896, when the first group literary movement started, and 1923, when the Republic of Turkey was officially founded. Generally, there were three main literary movements during this time:

- The Edebiyyât-ı Cedîde ("New Literature") movement.

- The Fecr-i Âtî ("Dawn of the Future") movement.

- The Millî Edebiyyât ("National Literature") movement.

The New Literature Movement

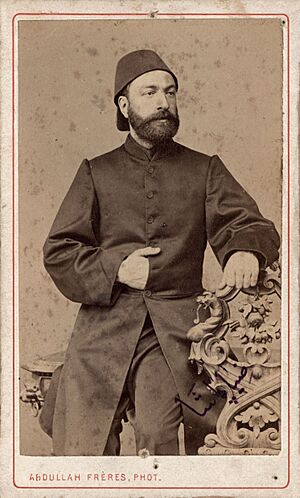

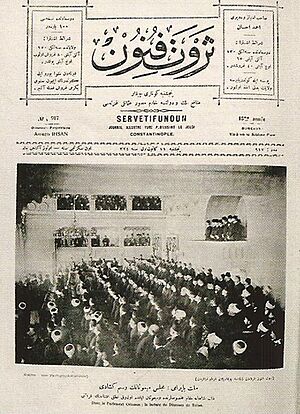

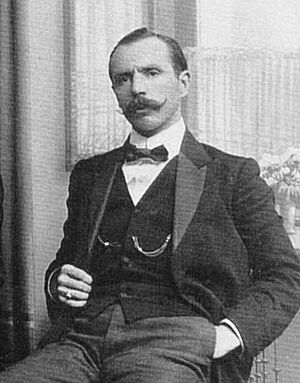

The Edebiyyât-ı Cedîde, or "New Literature," movement began with the founding of the magazine Servet-i Fünûn ("Scientific Wealth") in 1891. This magazine mostly focused on intellectual and scientific progress, following the Western model. So, the magazine's literary efforts, led by the poet Tevfik Fikret (1867–1915), aimed to create a Western-style "high art" in Turkey. The group's poetry, with Tevfik Fikret and Cenâb Şehâbeddîn (1870–1934) as the most important figures, was heavily influenced by the French Parnassian movement and the "Decadent" poets. The group's prose writers, especially Halit Ziya Uşaklıgil (1867–1945), were mainly influenced by Realism. However, the writer Mehmed Rauf (1875–1931) wrote the first Turkish psychological novel, Eylül ("September"), in 1901. The language of the Edebiyyât-ı Cedîde movement remained strongly influenced by Ottoman Turkish.

In 1901, because of an article called "Edebiyyât ve Hukuk" ("Literature and Law"), translated from French and published in Servet-i Fünûn, the magazine was shut down by the government of Ottoman sultan Abdülhamid II. Even though it was closed for only six months, the group's writers went their separate ways, and the Edebiyyât-ı Cedîde movement ended.

The Dawn of the Future Movement

In the February 24, 1909, edition of Servet-i Fünûn magazine, a group of young writers, who became known as the Fecr-i Âtî ("Dawn of the Future") group, released a statement. In it, they declared they were against the Edebiyyât-ı Cedîde movement. They followed the motto, "Sanat şahsî ve muhteremdir" ("Art is personal and sacred"). This motto was similar to the French writer Théophile Gautier's idea of "l'art pour l'art" (art for art's sake). However, the group was against simply bringing in all Western forms and styles. They wanted to create a literature that was clearly Turkish. But the Fecr-i Âtî group never clearly stated its goals, so it only lasted a few years before its members went their own ways. The two most important figures from this movement were Ahmed Hâşim (1884–1933) in poetry and Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu (1889–1974) in prose.

The National Literature Movement

In 1908, Sultan Abdülhamid II was forced to allow a new constitutional government. The parliament that was elected was almost entirely made up of members of the Committee of Union and Progress (also known as the "Young Turks"). The Young Turks (ژون تورکلر Jön Türkler) had opposed the increasingly authoritarian Ottoman government. They soon began to identify with a specific Turkish national identity. Along with this idea, the concept of a Turkish and even pan-Turkish nation (Turkish: millet) developed. So, the literature of this period became known as "National Literature" (Turkish: millî edebiyyât). During this time, the Ottoman Turkish language, which was influenced by Persian and Arabic, was definitely moved away from as a language for written literature. Literature began to assert itself as specifically Turkish, rather than Ottoman.

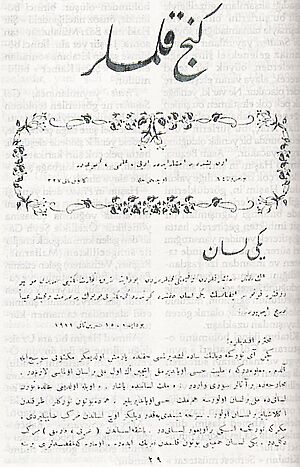

At first, this movement came together around the magazine Genç Kalemler (کنج قلملر; "Young Pens"). It was started in the city of Selânik in 1911 by three writers who best represented the movement: Ziya Gökalp (1876–1924), a sociologist and thinker; Ömer Seyfettin (1884–1920), a short-story writer; and Ali Canip Yöntem (1887–1967), a poet. In the first issue of Genç Kalemler, an article called "New Language" (Turkish: "Yeni Lisan") pointed out that Turkish literature had previously looked for inspiration either to the East (like the Ottoman Divan tradition) or to the West (like the Edebiyyât-ı Cedîde and Fecr-i Âtî movements). It had never looked to Turkey itself. This was the main goal of the National Literature movement.

However, the nationalistic nature of Genç Kalemler quickly became very chauvinistic (overly patriotic). Other writers, many of whom, like Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu, had been part of the Fecr-i Âtî movement, began to emerge from within the National Literature movement to counter this trend. Some of the more influential writers from this less extreme branch of the National Literature movement were the poet Mehmet Emin Yurdakul (1869–1944), the early feminist novelist Halide Edib Adıvar (1884–1964), and the short-story writer and novelist Reşat Nuri Güntekin (1889–1956).

Republican Literature

After the Ottoman Empire lost the First World War (1914–1918), the winning Entente Powers started to divide up the empire's lands and take control of them. To oppose this, the military leader Mustafa Kemal (1881–1938), who led the growing Turkish National Movement, organized the 1919–1923 Turkish War of Independence. This war ended with the official end of the Ottoman Empire, the removal of the Entente Powers, and the founding of the Republic of Turkey.

The literature of the new republic mostly came from the National Literature movement that existed before independence. It had roots in both the Turkish folk tradition and the Western idea of progress. An important change to Turkish literature happened in 1928. Mustafa Kemal started the creation and spread of a modified version of the Latin alphabet to replace the Arabic-based Ottoman script. Over time, this change, along with changes in Turkey's education system, led to more people being able to read and write in the country.

Prose in the Republic

In terms of style, the prose of the early years of the Republic of Turkey continued the National Literature movement. Realism and Naturalism were the main styles. This trend reached its peak with the 1932 novel Yaban ("The Wilds") by Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu. This novel can be seen as a starting point for two trends that would soon develop: social realism and the "village novel" (köy romanı). Çalıkuşu ("The Wren") by Reşat Nuri Güntekin deals with similar themes as Karaosmanoğlu's works. Güntekin's writing style is detailed and precise, with a realistic tone.

The social realist movement is best shown by the short-story writer Sait Faik Abasıyanık (1906–1954). His work sensitively and realistically describes the lives of the lower classes and ethnic minorities in cosmopolitan Istanbul. These subjects led to some criticism in the nationalistic mood of the time. The "village novel" tradition, on the other hand, started a bit later. As its name suggests, the "village novel" realistically deals with life in the villages and small towns of Turkey. The main writers in this tradition are Kemal Tahir (1910–1973), Orhan Kemal (1914–1970), and Yaşar Kemal (1923[?]–2015). Yaşar Kemal, in particular, became famous outside of Turkey not only for his novels, many of which, like İnce Memed (Memed, My Hawk) from 1955, turn local tales into epics, but also for his strong leftist political views. In a very different style, but showing a similar strong political viewpoint, were the satirical short-story writer Aziz Nesin (1915–1995) and Rıfat Ilgaz (1911–1993).

Another novelist who lived at the same time but was outside the social realist and "village novel" traditions is Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar (1901–1962). Besides being an important essayist and poet, Tanpınar wrote several novels. These include Huzur ("A Mind at Peace", 1949) and Saatleri Ayarlama Enstitüsü ("The Time Regulation Institute", 1961). These novels show the conflict between East and West in modern Turkish culture and society. Similar problems are explored by the novelist and short-story writer Oğuz Atay (1934–1977). However, unlike Tanpınar, Atay wrote in a more modernist and existentialist way in works like his long novel Tutunamayanlar ("The Good for Nothing", 1971–1972) and his short story "Beyaz Mantolu Adam" ("Man in a White Coat", 1975). On the other hand, Onat Kutlar's İshak ("Isaac", 1959), made up of nine short stories written mostly from a child's point of view and often surreal and mystical, is an early example of magic realism.

The tradition of literary modernism also influences the work of female novelist Adalet Ağaoğlu (1929– ). Her three novels called Dar Zamanlar ("Tight Times", 1973–1987) look at the changes in Turkish society between the 1930s and 1980s. She uses an innovative style. Orhan Pamuk (1952– ), who won the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature, is another innovative novelist. His works, like Beyaz Kale ("The White Castle") from 1990, Kara Kitap ("The Black Book"), and Benim Adım Kırmızı ("My Name is Red") from 1998, are influenced more by postmodernism than by modernism. This is also true for Latife Tekin (1957– ). Her first novel Sevgili Arsız Ölüm ("Dear Shameless Death", 1983) shows the influence of both postmodernism and magic realism. Elif Şafak has been one of the most outstanding authors of Turkish literature in the 2000s. She is known for her wide vocabulary and became a pioneer in Turkish literature internationally as a bilingual author who writes in both Turkish and English.

Poetry in the Republic

In the early years of the Republic of Turkey, there were several poetry trends. Authors like Ahmed Hâşim and Yahyâ Kemâl Beyatlı (1884–1958) continued to write important formal poems. Their language was largely a continuation of the late Ottoman tradition. However, most of the poetry at the time was in the folk-inspired "syllabist" movement (Beş Hececiler). This movement came from the National Literature movement and often expressed patriotic themes using the syllabic meter found in Turkish folk poetry.

The first big step away from this trend was taken by Nâzım Hikmet Ran. While he was a student in the Soviet Union from 1921 to 1924, he discovered the modernist poetry of Vladimir Mayakovsky and others. This inspired him to start writing poetry in a less formal style. At this time, he wrote the poem "Açların Gözbebekleri" ("Pupils of the Hungry"), which brought free verse into the Turkish language for the first time. Much of Nâzım Hikmet's later poetry continued to be written in free verse. However, his work had little influence for some time because it was censored due to his Communist political views. These views also led to him spending several years in prison. Over time, in books like Simavne Kadısı Oğlu Şeyh Bedreddin Destanı ("The Epic of Shaykh Bedreddin, Son of Judge Simavne", 1936) and Memleketimden İnsan Manzaraları ("Human Landscapes from My Country", 1939), he developed a voice that was both strong and subtle.

Another revolution in Turkish poetry happened in 1941 with the publication of a small book of poems called Garip ("Strange"), which included an essay. The authors were Orhan Veli Kanık (1914–1950), Melih Cevdet Anday (1915–2002), and Oktay Rifat (1914–1988). They openly opposed everything that had come before in poetry. Instead, they wanted to create popular art, "to explore the people's tastes, to determine them, and to make them reign supreme over art." To do this, and partly inspired by French poets like Jacques Prévert, they used a form of free verse introduced by Nâzım Hikmet. They also used very everyday language and wrote mainly about ordinary daily subjects and common people. The reaction was immediate and divided: most academics and older poets criticized them, while much of the Turkish population loved them. Although the movement itself lasted only ten years (until Orhan Veli's death in 1950, after which Melih Cevdet Anday and Oktay Rifat moved to other styles), its effect on Turkish poetry is still felt today.

Just as the Garip movement was a reaction against earlier poetry, there was also a reaction against the Garip movement in the 1950s and later. The poets of this new movement, soon known as İkinci Yeni ("Second New"), were against the social themes common in the poetry of Nâzım Hikmet and the Garip poets. Instead, partly inspired by the way language was broken apart in Western movements like Dada and Surrealism, they aimed to create more abstract poetry. They did this by using surprising and unexpected language, complex images, and linking ideas in new ways. In some ways, the movement shares characteristics with postmodern literature. The most famous poets writing in the "Second New" style were Turgut Uyar (1927–1985), Edip Cansever (1928–1986), Cemal Süreya (1931–1990), Ece Ayhan (1931–2002), Sezai Karakoç (1933– ), and İlhan Berk (1918–2008).

Outside of the Garip and "Second New" movements, many other important poets have also thrived. These include Fazıl Hüsnü Dağlarca (1914–2008), who wrote poems about big ideas like life, death, God, time, and the universe. Behçet Necatigil (1916–1979) wrote somewhat allegorical poems that explored the meaning of middle-class daily life. Can Yücel (1926–1999), besides his own very informal and varied poetry, also translated many world literature works into Turkish. İsmet Özel (1944– ), whose early poetry was very leftist, but whose poetry since the 1970s has shown a strong mystical and even Islamist influence. And Hasan Hüseyin Korkmazgil (1927–1984) wrote collectivist-realist poetry.

Important Works of Fiction: 1860–Present

|

|

| İbrahim Şinasi |

Halide Edib Adıvar |

|

| | |

| Halit Ziya Uşaklıgil |

Tarık Buğra |

|

|

| Füruzan |

Halikarnas Balıkçısı |

- 1860 Şair Evlenmesi by İbrahim Şinasi

- 1873 Vatan Yahut Silistre by Namık Kemal

- 1900 Aşk-ı Memnu by Halit Ziya Uşaklıgil

- 1919 Memleket Hikayeleri by Refik Halit Karay

- 1922 Çalıkuşu by Reşat Nuri Güntekin

- 1930 Dokuzuncu Hariciye Koğuşu by Peyami Safa

- 1932 Yaban by Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu

- 1936 Sinekli Bakkal by Halide Edib Adıvar

- 1938 Üç İstanbul by Mithat Cemal Kuntay

- 1941 Fahim Bey ve Biz by Abdülhak Şinasi Hisar

- 1943 Kürk Mantolu Madonna by Sabahattin Ali

- 1944 Aganta Burina Burinata by Halikarnas Balıkçısı

- 1949 Huzur by Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar

- 1952 Dost by Vüs'at O. Bener

- 1954 Alemdağda Var Bir Yılan by Sait Faik Abasıyanık

- 1954 Bereketli Topraklar Üzerinde by Orhan Kemal

- 1955 İnce Memet by Yaşar Kemal

- 1956 Esir Şehrin İnsanları by Kemal Tahir

- 1959 Yılanların Öcü by Fakir Baykurt

- 1959 Aylak Adam by Yusuf Atılgan

- 1960 Ortadirek by Yaşar Kemal

- 1962 Saatleri Ayarlama Enstitüsü by Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar

- 1964 Küçük Ağa by Tarık Buğra

- 1966 Memleketimden İnsan Manzaraları by Nâzım Hikmet

- 1971 Tutunamayanlar by Oğuz Atay

- 1973 Parasız Yatılı by Füruzan

- 1973 Anayurt Oteli by Yusuf Atılgan

- 1979 Bir Düğün Gecesi by Adalet Ağaoğlu

- 1982 Cevdet Bey ve Oğulları by Orhan Pamuk

- 1983 Sevgili Arsız Ölüm by Latife Tekin

- 1990 Kara Kitap by Orhan Pamuk

- 1995 Puslu Kıtalar Atlası by İhsan Oktay Anar

- 1998 Benim Adım Kırmızı by Orhan Pamuk

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Literatura de Turquía para niños

In Spanish: Literatura de Turquía para niños

- Contemporary Turkish literature

- Crimean Tatar literature

- Azerbaijani literature

- Turkmen literature

- Chagatai language

- Codex Cumanicus

- List of Ottoman poets

- List of contemporary Turkish poets

- List of Turkish short story writers

- List of Turkish women writers

- List of Turkish writers

- Persian metres

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |