Codex Cumanicus facts for kids

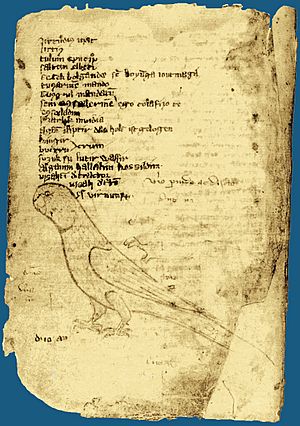

The Codex Cumanicus is a very old language book from the Middle Ages. It was made to help Catholic missionaries talk with the Cumans. The Cumans were a group of nomadic (traveling) Turkic people. This special book is kept safe today in the Library of St. Mark in Venice, Italy.

This book was created in Crimea. It is seen as one of the oldest examples of the Crimean Tatar language. It's super important for understanding the history of different Turkic languages, especially those spoken by the Kypchaks (also known as Polovtsy or Kumans) who lived in the Black Sea steppes and the Crimean peninsula.

Contents

What is the Codex Cumanicus?

The Codex Cumanicus is like a guide to the Cuman language. It helped people from different cultures understand each other. This was very useful for traders, leaders, and missionaries who needed to communicate with the Cumans.

How it was Made and What's Inside

The Codex Cumanicus has two main parts. It probably grew over time, with different people adding to it. The copy we have today in Venice is from July 11, 1303.

Part One: Learning Languages

The first part of the book is like a language learning tool. It has a dictionary with words in Latin, Persian, and Cuman. These words are written using the Latin alphabet. There's also a list of Cuman verbs, names, and pronouns, with their meanings in Latin. This part was made to help people learn the Cuman language for everyday use.

Part Two: Spreading Ideas

The second part of the Codex Cumanicus has a Cuman-German dictionary. It also includes information about Cuman grammar. This section was created to help spread Christianity among the Cumans. It has many quotes from religious books translated into Cuman. You can also find Cuman words, phrases, sentences, and about 50 riddles. Plus, there are stories about the lives and work of religious leaders.

Ancient Riddles

The "Cuman Riddles" found in the Codex are very important. They help us learn about the old stories and traditions of early Turkic people. One expert, Andreas Tietze, said these riddles are the earliest versions of riddle types that are common across many Turkic nations.

Here are some examples of the riddles from the Codex:

- The white yurt has no mouth (opening). That is the egg.

- My bluish kid at the tethering rope grows fat, The melon.

- Where I sit is a hilly place. Where I tread is a copper bowl. The stirrup.

An Example: The Lord's Prayer

To show you what the Cuman language looked like in the Codex, here is the "Lord's Prayer" written in Cuman, along with its English, Turkish, and Crimean Tatar translations:

| Cuman |

Atamız kim köktäsiñ. Alğışlı bolsun seniñ atıñ, kelsin seniñ xanlığıñ, bolsun seniñ tilemekiñ — neçik kim köktä, alay [da] yerdä. Kündeki ötmäkimizni bizgä bugün bergil. Dağı yazuqlarımıznı bizgä boşatqıl — neçik biz boşatırbız bizgä yaman etkenlergä. Dağı yekniñ sınamaqına bizni quvurmağıl. Basa barça yamandan bizni qutxarğıl. Amen! |

|---|---|

| English |

Our Father which art in heaven. Hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done in earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive us our sins as we forgive those who have done us evil. And lead us not into temptation, But deliver us from evil. Amen. |

| Turkish |

Atamız ki göktesin. Alkış olsun senin adın, gelsin senin hanlığın, olsun senin dilediğin – nice ki gökte, öyle de yerde. Bugün, gündelik ekmeğimizi bize ver. Günahlarımızı bağışla – nice ki bağışlarız biz, bize yamanlık edenleri. Ve bizi kötülüğün sınamasından kurtar. Tüm yamandan bizi kurtar. Amin! |

| Crimean Tatar |

Atamız kim köktesiñ. Alğışlı olsun seniñ adıñ, kelsin seniñ hanlığıñ, olsun seniñ tilegeniñ — nasıl kökte, öyle [de] yerde. Kündeki ötmegimizni bizge bugün ber. Daa yazıqlarımıznı (suçlarımıznı) bizge boşat (bağışla) — nasıl biz boşatamız (bağışlaymız) bizge yaman etkenlerge. Daa şeytannıñ sınağanına bizni qoyurma. Episi yamandan bizni qurtar. Amin! |

See also

In Spanish: Codex Cumanicus para niños

In Spanish: Codex Cumanicus para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |