Jats facts for kids

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| South Asia | ~30–43 million (c. 2009/10) |

| Languages | |

| Hindustani (Hindi-Urdu) • Haryanvi • Punjabi (and its dialects) • Lahnda • Rajasthani • Sindhi (and its dialects) • Braj • Khariboli | |

| Religion | |

| Hinduism • Islam • Sikhism | |

The Jat people are a large community mainly found in Northern India and Pakistan. They traditionally worked in agriculture, meaning they were farmers.

Originally, Jats were herders in the lower Indus river valley. Over time, they moved north into the Punjab region. Later, in the 17th and 18th centuries, they spread into areas like Delhi Territory, Rajputana, and the western Gangetic Plain.

Today, Jats follow different religions, including Hinduism, Islam, and Sikhism. You can find them mostly in the Indian states of Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan. In Pakistan, they live in the provinces of Sindh and Punjab.

In the late 1600s and early 1700s, the Jats fought against the Mughal Empire. Gokula, a Hindu Jat leader, was one of the first to rebel. The Hindu Jat kingdom became very strong under Maharaja Suraj Mal (1707–1763). Jats also played a big part in developing the Khalsa, a special group within Sikhism.

By the 1900s, Jats who owned land became very powerful in North India. This included areas like Punjab, Western Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Haryana, and Delhi. Many Jats later moved from farming to city jobs. They used their strong economic and political position to gain higher social standing.

Contents

History of the Jat People

The Jats are a great example of how communities and identities formed in early modern Indian subcontinent. The word "Jat" could describe many people. It ranged from simple farmers who owned land to rich and powerful Zamindars (landlords).

When Muhammad bin Qasim conquered Sind in the 700s, Arab writers mentioned groups of Jats. These Jats lived in different parts of Sind. The Arab rulers kept the Jats in their existing social positions. They also continued some unfair practices against them from earlier Hindu rule.

Between the 1000s and 1500s, Jat herders from Sind moved north. They followed the river valleys into the Punjab region. Many Jats started farming in areas like western Punjab. This was especially true after the sakia (water wheel) was introduced.

By the early Mughal period, "Jat" in Punjab often meant "peasant" or farmer. Some Jats began to own land and gain local power. The Jats started as herders in the Indus valley. Slowly, they became farmers. Around 1595, Jat Zamindars controlled over 32% of the land in Punjab.

Historians Catherine Asher and Cynthia Talbot explain how Jat religious identities changed. Before settling, the Jat herders didn't have much exposure to major religions. As they became more involved in farming life, they adopted the main religion of the people around them.

Over time, Jats in western Punjab became mostly Muslim. In eastern Punjab, they became Sikh. In the areas between Delhi Territory and Agra, they became Hindu. These religious divisions matched where these religions were strongest.

During the decline of the Mughal empire in the early 1700s, people from the countryside became more involved with townspeople and farmers. Many new rulers of this time came from these armed, nomadic groups. This interaction greatly affected India's social structure for a long time.

At this time, ordinary farmers and herders like the Jats were part of a social group. This group blended into the rich landowning classes on one side. On the other side, it blended into lower-status groups. During the Mughal Empire's strongest period, Jats had recognized rights. Historians Barbara D. Metcalf and Thomas R. Metcalf say that groups like the Jats grew stronger because of the Mughal system. This system gave them military and governing experience.

As the Mughal Empire weakened, there were many rebellions in North India. These were sometimes called "peasant rebellions." However, small local landowners, or zemindars, often led these uprisings. The Sikh and Jat rebellions were led by these local landowners. They had close ties with each other and with the farmers under them. They were also often armed.

These rising groups of farmer-warriors were not old, established Indian castes. They were new groups without fixed social ranks. They could include older farming castes, various warlords, and nomadic groups. Even at its peak, the Mughal Empire didn't directly control all its rural leaders. These landowners gained the most from the rebellions. They increased the land they controlled. Some even became minor princes, like the Jat ruler Badan Singh of the princely state of Bharatpur.

Hindu Jats

In 1669, Hindu Jats, led by Gokula, rebelled against the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in Mathura. After 1710, this community became very strong south and east of Delhi. Historian Christopher Bayly noted that men once seen as robbers by the Mughals had formed small states by the end of the century. These states were connected by marriages and shared religious practices.

The Jats moved into the Gangetic Plain in two big waves. This happened in the 1600s and 1700s. They were not a caste in the usual Hindu way. Instead, they were a broad group of farmer-warriors. According to Christopher Bayly, this was a society where Brahmins were few. Jat men married into many lower farming and business castes. A kind of group pride, rather than strict caste rules, guided them.

By the mid-1700s, the ruler of the new Jat kingdom of Bharatpur, Raja Surajmal, felt confident. He built a beautiful garden palace at nearby Deeg. Historian Eric Stokes said that when Bharatpur's power was high, Jat fighting groups moved into new areas. They often took land from Rajput groups. But this political power was too weak and short-lived to cause big changes.

Muslim Jats

When Arabs came to Sindh and other southern parts of Pakistan in the 600s, they found the Jats and the Med people. Early Arab writings often called these Jats Zatts. The Arab conquest records also show that many Jats lived in towns and forts in Lower and Central Sindh. Today, Muslim Jats live in both Pakistan and India.

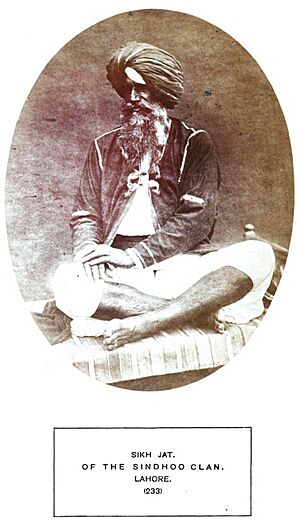

Sikh Jats

Some important Sikh figures, like Baba Buddha, were early Sikhs. Many Jats converted to Sikhism as early as the time of Guru Angad (1504–1552). However, the first large-scale conversions of Jats are thought to have started during the time of Guru Arjan (1563–1606).

Guru Arjan traveled through eastern Punjab. He founded important towns like Tarn Taran Sahib, Kartarpur, and Hargobindpur. These towns became social and economic centers. The Darbar Sahib was also completed with community funds. It became a central place for Sikh activities. This helped create a strong Sikh community, especially with many Jat farmers joining. They led the Sikh resistance against the Mughal Empire from the 1700s onwards.

It is believed that the Sikh community became more military-focused after Guru Arjan's death. This started during Guru Hargobind's time and continued later. The large number of Jats in the community might have influenced this change, and vice versa.

At least eight of the 12 Sikh Misls (Sikh groups) were led by Jat Sikhs. They made up most of the Sikh chiefs.

During the colonial period in the early 1900s, more Jats continued to convert from Hinduism to Sikhism. The Sikh writer, Khushwant Singh, said that Jats in Punjab never fully accepted the traditional Hindu caste system. The British also played a role in increasing the Sikh Jat population. They encouraged Hindu Jats to become Sikhs to get more Sikh soldiers for their army.

In Punjab, the states of Patiala, Faridkot, Jind, and Nabha were ruled by Sikh Jats.

Jat Population and Influence

According to Sunil K. Khanna, an anthropologist, there were about 30 million Jats in South Asia in 2010. This number is based on old records and population growth. The last caste census in 1931 estimated 8 million Jats. Deryck O. Lodrick estimates over 33 million Jats in South Asia in 2009. He notes that some estimates suggest their total population could be around 43 million.

Jats in India

In India, recent estimates show Jats make up a large part of the population. They are 20–25% in Haryana and 20–35% in Punjab. In Rajasthan, Delhi, and Uttar Pradesh, they are about 9%, 5%, and 1.2% of the population, respectively.

In the 1900s and more recently, Jats have been very powerful in politics in Haryana and Punjab. Some Jats have become important political leaders. These include Charan Singh, who was the sixth Prime Minister of India, and Chaudhary Devi Lal, who was the sixth Deputy Prime Minister of India.

After India became independent, Jats gained more economic power and took part in elections. This helped them greatly influence politics in North India. You can see clear differences in wealth, movement, and jobs among the Jat people.

Jats are listed as Other Backward Class (OBC) in seven Indian states and territories. These include Rajasthan, Himachal Pradesh, Delhi, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh. However, only Jats from most of Rajasthan can get special benefits for central government jobs. In 2016, Jats in Haryana held big protests. They demanded to be classified as OBC to get these benefits.

Jats in Pakistan

Many Jat Muslim people live in Pakistan. They play important roles in public life in Pakistani Punjab and across Pakistan. Jat communities also live in Pakistani-administered Kashmir and Sindh. They are especially found in the Indus River Delta. You can also find them among Seraiki-speaking groups in southern Pakistani Punjab. They also live in the Kachhi region of Balochistan and the Dera Ismail Khan District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

In Pakistan, Jat people have also become notable political leaders. One example is Hina Rabbani Khar.

Jat Culture and Society

Military Service

Many Jat people serve in the Indian Army. They are part of regiments like the Jat Regiment, Sikh Regiment, Rajputana Rifles, and the Grenadiers. They have won many top military awards for their bravery. Jat people also serve in the Pakistan Army, especially in the Punjab Regiment.

Officials during the British Raj called the Jat people a "martial race". This meant the British preferred them for recruitment into the British Indian Army. This term was used to classify groups as either "martial" (brave and good fighters) or "non-martial" (unfit for battle). The British believed "martial races" were brave but also easy to control. They preferred to recruit those with less education.

The Jats fought in both World War I and World War II as part of the British Indian Army. After 1881, the British changed their policies. To be recruited into the army, it became necessary to be Sikh. This was because the British believed Hindus were less suitable for military purposes.

In 2013, the Indian Army stated that the 150-member Presidential Bodyguard only included Hindu Jats, Jat Sikhs, and Hindu Rajputs. They said this was for "functional" reasons, not based on caste or religion.

Religious Beliefs

Deryck O. Lodrick estimates the religious breakdown of Jats as follows: 47% are Hindus, 33% are Muslims, and 20% are Sikhs.

Jats have a practice of praying to their dead ancestors. This practice is called Jathera.

Social Status (Varna)

There are different ideas among scholars about the varna (social class) status of Jats in Hinduism. Historian Satish Chandra says the varna of Jats was "uncertain" during the medieval period. According to anthropologist Indera Paul Singh, Brahmins lowered the varna status of Jats to Sat Shudra (clean Shudra). This happened in the Vedic period because Jats challenged the Brahmins' authority.

Historian Irfan Habib states that Jats were a "pastoral Chandala-like tribe" in Sindh in the 700s. Their status changed from Shudra varna in the 1000s to Vaishya varna by the 1600s. Some Jats wanted to improve their status even more after their rebellion against the Mughals in the 1600s.

During the later years of British rule, Rajputs did not accept Jat claims to Kshatriya (warrior class) status. This disagreement often led to fights between the two groups. The Arya Samaj, a reform movement popular among Jats, supported the claim to Kshatriya status. They saw this as a way to counter the colonial idea that Jats were not of Aryan descent.

Jat Clan System

The Jat people are divided into many different clans. Some of these clans are also found in other groups. Hindu and Sikh Jats practice clan exogamy. This means they marry outside their own clan.

List of Clans

- Ahlawat

- Anjana Chaudhari

- Aulakh

- Bagri

- Bajwa

- Babbar

- Beniwal

- Bharwana

- Brar

- Buttar

- Cheema

- Dabas

- Dahiya

- Dharan

- Dhaliwal

- Dhillon

- Gill

- Grewal

- Khakh

- Khangura

- Kharal

- Lashari

- Malhi

- Malik

- Marhal

- Maulaheri

- Mirdha

- Muley

- Naich

- Panwar

- Poonia

- Rahal

- Rahar

- Randhawa

- Ranjha

- Rath

- Rehvar

- Sahota

- Sandhawalia

- Sandhu

- Sangwan

- Sekhon

- Sial

- Sidhu

- Tarar

- Teotia

- Thaheem

- Tomar

- Virk

- Warraich

Notable People

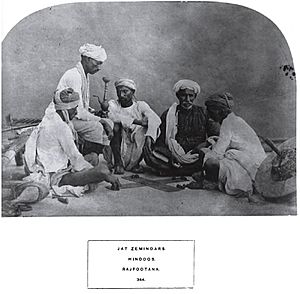

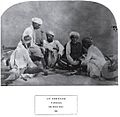

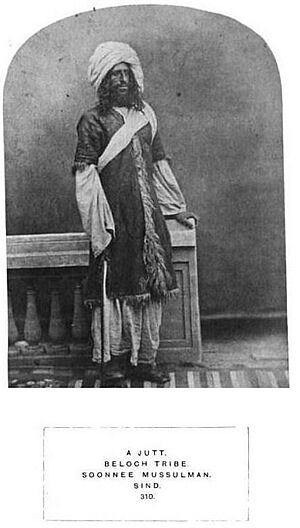

Images for kids

-

Jat girl from Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India, 1868.

-

The durbar of the teenage Hindu Jat ruler of Bharatpur, a princely state in Rajasthan, early 1860s.

See also

In Spanish: Jat para niños

In Spanish: Jat para niños

- Jat Regiment

- Jat reservation agitation

- Meo (ethnic group)

- World Jat Aryan Foundation

- List of Jat dynasties and states

- List of Jat people

- Jat Sikh

- Jāti

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |