Henry Every facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henry Every

|

|

|---|---|

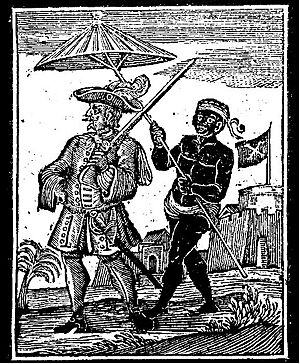

An woodcut from A General History of the Pyrates (1725)

|

|

| Born | 20 August 1659 |

| Disappeared | June 1696 (aged 36) |

| Spouse(s) | Dorothy Arther |

| Piratical career | |

| Nickname | Long Ben The Arch Pirate The King of Pirates |

| Allegiance | None |

| Years active | 1694 – 1696 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Base of operations | Atlantic Ocean, along the Pirate Round, and the Indian Ocean |

| Commands | Fancy, formerly Charles II |

| Wealth | At least 11 vessels captured by September 1695, including the Ganj-i-Sawai |

Henry Every, also known as Henry Avery, was a famous English pirate who sailed the Atlantic and Indian oceans in the mid-1690s. He was born on August 20, 1659, and disappeared in June 1696. People sometimes called him Long Ben.

Every was known as "The Arch Pirate" and "The King of Pirates." He was famous for being one of the few pirate captains who got away with his treasure without being caught or killed. He also carried out what many call the most profitable act of piracy in history. Even though he was a pirate for only two years, his adventures captured people's imaginations. He inspired others to become pirates and even appeared in books.

Every started his pirate life as the first mate on a warship called Charles II. The ship was docked in Corunna, Spain. The crew became unhappy because they weren't getting paid. They decided to take over the ship in a mutiny. They renamed Charles II to the Fancy, and Every was chosen as their new captain.

His most famous raid happened on September 7, 1695. He attacked a group of 25 ships belonging to the Grand Mughal. These ships were on their yearly trip to Mecca. Among them was the Ganj-i-Sawai, which was full of treasure, and its escort, Fateh Muhammed. Every teamed up with other pirate ships and led a small pirate fleet. They managed to capture a huge amount of gold and jewels, worth about £600,000 at the time. This caused big problems for England's relationship with the Mughals. A large reward of £1,000 was offered for Every's capture. This led to the first worldwide manhunt ever recorded.

Many of Every's crew members were later caught. But Every himself managed to escape. He disappeared from all records in 1696. No one knows what he did or where he went after that. Some stories say he changed his name and lived a quiet life in Britain or on a secret tropical island. Other stories say he lost all his riches. He is thought to have died sometime between 1699 and 1714. His treasure has never been found.

Contents

Every's Early Life

Where Every Came From

Historians believe Henry Every was born on August 20, 1659. This was in a village called Newton Ferrers in Devon, England. Records show his parents were John and Anne Evarie. His family was well-known in Devon.

One of Every's crew members, William Phillips, said in 1696 that Every was "about 40 years old." He also said Every's mother lived "near Plymouth." Every was married to Dorothy Arther. They got married in London on September 11, 1690. There is no proof that he had any children.

The first book about Every's life was written in 1709. It said he was born in 1653 in Cattedown, Plymouth. This information is now known to be wrong. Many later books, like Daniel Defoe's The King of Pirates (1720), used this incorrect information.

Some people thought Every's real name was Benjamin Bridgeman. This was because he was nicknamed "Long Ben." But historians now agree that "Henry Every" was his true name. He used this name when he joined the Royal Navy. He only used "Bridgeman" after he became a pirate.

Henry Every was probably a sailor from a young age. He served on different ships in the Royal Navy. Records show that in March 1689, he was a midshipman on a ship called HMS Rupert. This was during the Nine Years' War against France.

Every was promoted to Master's mate in July 1689. In June 1690, he joined Captain Wheeler on a new ship, HMS Albemarle. He likely fought in the Battle of Beachy Head against the French. This battle was a disaster for the English. Every left the Royal Navy on August 29, 1690.

After leaving the Navy, Every became involved in the Atlantic slave trade. He worked for the governor of Bermuda, Isaac Richier. Every's job was to transport enslaved Africans from West Africa to the Americas. He was known for tricking other slave traders. He would fly friendly flags to get them to board his ship. Then he would capture them and their enslaved people.

Every's Pirate Adventures

The Mutiny and Becoming a Captain

In the spring of 1693, some London investors started a big project. It was called the Spanish Expedition Shipping. They had four warships, including the Charles II. The plan was to sail to the Spanish West Indies. There, they would trade, give weapons to the Spanish, and find treasure from sunken ships. They also planned to attack French ships. The investors promised to pay the sailors well.

Every joined the Spanish Expedition as first mate. The ships were led by Admiral Sir Don Arturo O'Byrne. The journey quickly ran into problems. The ships took five months to reach Corunna, Spain. They were supposed to arrive in two weeks. Even worse, the legal papers from Madrid didn't arrive. The ships had to wait for months. The sailors had no money to send home. They felt trapped in Corunna.

The sailors asked for their pay, but their request was denied. Many sailors became desperate. They thought they had been sold into slavery to the Spanish. On May 1, the fleet was finally getting ready to leave. The men demanded their six months of pay. If not, they threatened to strike. Admiral O'Byrne wrote to England asking for the money. But on May 6, some sailors argued with O'Byrne. This is probably when they planned to mutiny. Every was one of the men recruiting others. He told them, "come on board him, & he would carry them where they should get money enough." Every had a lot of experience. He was also from a lower social class. This made him a good choice to lead the mutiny. The crew believed he would look out for them.

On May 7, 1694, Every and about 25 other men took over the Charles II. Captain Gibson was sick in bed, so no one was hurt. Every offered to let Captain Gibson command the ship if he joined them. Gibson refused and was put ashore with other sailors. Only the ship's surgeon was kept, as his skills were needed. All the men left on board the Charles II chose Every as their captain.

Every easily convinced the men to sail to the Indian Ocean as pirates. Their original mission was already similar to piracy. Every was known for being very persuasive. He might have mentioned how successful Thomas Tew was in the Red Sea a year earlier. The crew decided that each member would get one share of the treasure. The captain would get two shares. Every then renamed Charles II to the Fancy. This name showed their new hope and the ship's good quality. They then set sail for the Cape of Good Hope.

The Pirate Round Journey

At Maio, Every committed his first act of piracy. He robbed three English merchant ships from Barbados for food and supplies. Nine men from these ships joined Every's crew. His crew now had about 94 men. Every then sailed to the Guinea coast. There, he tricked a local chief into boarding the Fancy. He pretended to trade, but then took the chief's wealth and left him and his men as slaves.

Every continued along the African coast. He stopped at Bioko where the Fancy was repaired and made faster. They cut away some parts of the ship to make it quicker. This made the Fancy one of the fastest ships in the Atlantic Ocean. In October 1694, the Fancy captured two Danish ships near Príncipe. They took ivory and gold. About 17 Danish sailors joined Every's crew.

In early 1695, the Fancy sailed around the Cape of Good Hope. They stopped in Madagascar to get more supplies. Next, they stopped at Johanna in the Comoros Islands. Here, Every's crew rested. They also captured a French pirate ship. They looted it and about 40 French pirates joined them. Every now had about 150 men.

At Johanna, Every wrote a letter to English ship commanders in the Indian Ocean. He falsely said he had not attacked any English ships. He described a secret signal English captains could use to identify themselves. This way, he could avoid them. He warned that he might not be able to stop his crew from robbing ships if they didn't use the signal. This letter might have been a trick to avoid the powerful ships of the East India Company (EIC). But it did not stop the English from hunting him.

Capturing the Grand Mughal's Fleet

In 1695, Every sailed to the island of Perim. He waited there for an Indian fleet to pass by. This fleet was the richest prize in Asia. Any pirates who captured it would have the most profitable pirate raid ever. In August 1695, the Fancy reached the Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb. Every joined forces with five other pirate captains. These included Thomas Tew on the Amity and Joseph Faro on Portsmouth Adventure. Every was chosen to lead this new fleet of six pirate ships. He now commanded over 440 men.

They waited for the Indian fleet. A group of 25 ships from the Mughal Empire was spotted. This included the huge 1,600-ton Ganj-i-sawai with 80 cannons and 1,100 crew. Its escort was the even larger 3,200-ton Fateh Muhammed with 94 cannons and 800 crew. The pirate fleet chased them. The Fateh Muhammed had treasure worth about £50,000 to £60,000. But when this was shared, Every's crew got only small amounts.

The Ganj-i-sawai was a strong opponent. It had 80 guns and 400 guards with muskets. It also carried 600 other passengers. Every's crew, joined by the crew of Pearl, fought a fierce hand-to-hand battle. It lasted two to three hours.

An Indian historian, Muhammad Hashim Khafi Khan, was in Surat at the time. He wrote that when Every's men boarded the ship, the captain of Ganj-i-sawai ran below deck. He armed the slave girls and sent them to fight the pirates. Khafi Khan blamed Captain Ibrahim for the loss. He wrote that if the captain had fought back, the pirates would have been defeated.

The pirates forced their captives to tell them where the treasure was hidden. The survivors were left on their ships, which the pirates set free. The treasure from Ganj-i-sawai was huge. It was between £200,000 and £600,000. This included 500,000 gold and silver coins. It might have been the richest ship ever taken by pirates.

The Hunt for Every

The attack on Emperor Aurangzeb's treasure ship caused big problems for the English. The East India Company (EIC) was already struggling. Every's attack threatened all English trade in India. The local Indian governor arrested English people in Surat. He did this as punishment and to protect them from angry locals. Emperor Aurangzeb was furious. He closed four of the EIC's trading posts in India. He also put their officers in prison. He almost ordered an attack on the English city of Bombay. His goal was to kick the English out of India forever.

To calm Aurangzeb, the EIC promised to pay for all the damage. The Parliament declared the pirates "the enemy of humanity." In mid-1696, the government offered a £500 reward for Every's capture. They also offered a free pardon to anyone who told them where he was. The EIC later doubled the reward to £1,000. This started the first worldwide manhunt in history.

Every's Escape to New Providence

Historian Douglas R. Burgess believes the Fancy reached St. Thomas. There, the pirates sold some of their treasure. In March 1696, the Fancy anchored near New Providence in the Bahamas. Four of Every's men went to Nassau, the capital city. They had a letter for the island's governor, Nicholas Trott. The letter said the Fancy had returned from Africa. The crew of 113 men needed time ashore. In return for letting the Fancy enter the harbor, the crew would pay Trott £860. Their captain, named "Henry Bridgeman," also promised the ship to the governor as a gift.

This was a tempting offer for Trott. The Nine Years' War had been going on for eight years. The island was very empty. Trott knew the French had recently captured a nearby island. They were heading for New Providence. Nassau only had 60 or 70 men. If the Fancy crew stayed, it would double the island's male population. The armed ship in the harbor might also stop a French attack. Also, the bribe was three times Trott's yearly salary.

Trott allowed the Fancy to enter the harbor. He later met Every in person. The Fancy was given to the governor. He found extra bribes inside, like ivory tusks and gunpowder. Trott must have known the crew were not just unlicensed traders. He likely saw the battle damage on the Fancy. When news came that the Royal Navy was hunting for the Fancy and "Captain Bridgeman" was Every, Trott denied knowing anything. He said the islanders "saw no reason to disbelieve them."

Every's men were free to go to the town's pubs. But they were disappointed with the Bahamas. The islands were empty, so there was nowhere to spend their money. The pirates spent months living in boredom. Trott took everything valuable from the Fancy. The ship was later lost after hitting rocks. This might have been on purpose by Trott to get rid of evidence.

Every's Disappearance

Burgess suggests that when the order for Every's arrest reached Trott, he had to act. He alerted the authorities but also warned Every and his crew. Every's 113-person crew quickly escaped. Only 24 men were ever caught, and five were executed. Every himself was never seen again. He told his men different stories about where he was going. This was likely to throw off anyone chasing him.

Some believe Every's crew split up. Some stayed in the West Indies. Most went to North America. The rest, including Every, returned to England. Every and about 20 men sailed to Ireland in a ship called Sea Flower. They raised suspicion when unloading their treasure. Two men were caught. But Every managed to escape again.

What Happened to Every?

British writer Charles Johnson suggested that Every died poor in Devon. He said Bristol merchants cheated Every out of his wealth. But it's not clear how Johnson knew this. If Every was living in poverty, he likely would have been caught for the large reward. So, this story might have been told to teach a lesson about piracy.

Other stories say Every changed his name. He settled in Devon and lived peacefully. He supposedly died on June 10, 1714. However, the source for this is not very reliable. In 1781, a customs officer met someone who claimed to be Every's descendant. This person said Every "had died in Barnstaple, and was buried as a pauper."

For years after Every disappeared, people reported seeing him. But none of these sightings were true. After a made-up book about him came out in 1709, stories about Every became more like legends. They said he was a king ruling a pirate paradise in Madagascar. These stories were widely believed, but they were not real. No true information about Every's life after June 1696 ever came out.

A recent book from 2024 claims Every secretly became a spy for the Royal Navy. This idea is based on a coded letter supposedly from "Avery the Pirate."

What Happened to Every's Crew?

In the British Isles

John Dann, Every's coxswain, was arrested on July 30, 1696. He was caught for suspected piracy in Rochester, Kent. He had sewn £1,045 in gold coins into his waistcoat. His chambermaid found the money and reported it. To avoid being executed, Dann agreed to testify against other captured crew members.

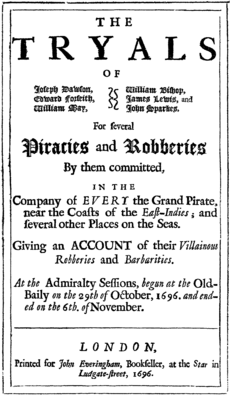

Soon after, 24 of Every's men were rounded up. Some were reported by jewelers after trying to sell their treasure. In the next few months, 15 pirates were put on trial. Six were found guilty. Piracy was a crime punishable by death. The testimony of Dann and another crew member, Middleton, was very important.

The six defendants were Joseph Dawson, Edward Forseith, William May, William Bishop, James Lewis, and John Sparkes. Their trial began on October 19, 1696. They were accused of piracy on the Ganj-i-Sawai. The government brought in the country's most important judges for the trial.

Even though the jury was pressured to find them guilty, they first said "not guilty." The court was shocked. Twelve days later, the pirates were tried again. This time, they were accused of planning to steal the Charles II. The court kept stressing that the pirates needed to be convicted. This time, the jury found them guilty.

The pirates were given one last chance to explain why they should not be executed. Most just claimed they didn't know what was happening and begged for mercy. May said he was sick and "never acted in all the voyage." Bishop reminded the court he was "forced away" and was only 18 during the mutiny. Dawson, who pleaded guilty, was spared. The others were sentenced to death. Sparkes was the only pirate to show some regret.

On November 25, 1696, the five prisoners were taken to the gallows at Execution Dock. They gave their final speeches before a crowd. They were hanged facing the River Thames, where their voyage had begun three years earlier.

Dann avoided hanging by becoming a witness for the King. He stayed in England. In 1699, Dann married Eliza Noble. The next year, he became a partner in a banking business. However, the bank later went out of business because of fraud. Dann died in 1722.

Every's Treasure

The Ganj-i-Sawai Treasure

The exact value of the Ganj-i-Sawai's cargo is not known for sure. Estimates at the time varied greatly. Some said £325,000, while others said £600,000. The Mughal authorities claimed £600,000. The East India Company (EIC) estimated the loss at about £325,000, but still filed a £600,000 insurance claim.

Some historians think the EIC gave a lower estimate to pay less in damages. Others believe the Mughal authorities gave a higher number to get more money from the English. Some historians say £325,000 was probably closer to the real value. This is partly because a merchant in Surat, Alexander Hamilton, agreed with that number.

Every's capture of Ganj-i-Sawai is often called the greatest pirate exploit. But it's possible other pirates took even more valuable treasure. In April 1721, John Taylor and Olivier Levasseur captured a Portuguese ship called Nossa Senhora do Cabo. This ship was heading to Lisbon from Goa. It was damaged in a storm and being repaired when the pirates attacked.

The ship was full of silver, gold, diamonds, and other jewels. It also had pearls, silks, spices, art, and church items. The total value of this treasure has been estimated from £100,000 to £875,000. If the higher number is correct, it would be much more than Every's haul.

Historian Jan Rogoziński called Cabo "the richest plunder ever captured by any pirate." He estimated its value at over $400 million today. In comparison, the EIC's estimate of £325,000 for Ganj-i-Sawai is worth at least $200 million. If the larger estimate of £600,000 is used, it would be about $400 million.

Other Ships Every Captured

The cargo from Fateh Muhammed was worth £50,000–60,000. This is about $30 million in today's money. Every is known to have captured at least 11 ships by September 1695. Besides the Emperor Aurangzeb's fleet, another valuable prize was Rampura. This trading ship gave Every a "surprising haul of 1,700,000 rupees."

Every's Lasting Impact

Every's adventures immediately fascinated the public. Some saw him as a brave pirate, like a sea-going Robin Hood. He represented the idea that rebellion and piracy could be ways to fight against unfair captains and societies. Every inspired many others to become pirates. Many famous pirates, like Blackbeard and Bartholomew Roberts, were children when Every became legendary.

English pirate Walter Kennedy learned Every's story when he was young. When Kennedy retired from piracy, he returned to London to spend his money. But his crimes caught up to him. In 1721, he was arrested and sentenced to death. While waiting for his execution, Kennedy loved telling stories about Every's adventures.

Every in Books and Plays

Several fictional and semi-true stories about Every were published after he disappeared. In 1709, a short book called The Life and Adventures of Capt. John Avery; the Famous English Pirate, Now in Possession of Madagascar came out. The author, using the name "Adrian van Broeck," claimed to be a Dutchman captured by Every. In this story, Every is a pirate and a romantic hero. After raiding the Mughal's ship, he runs off with and marries the Emperor's daughter. They escape to Saint Mary's Island. There, Every creates a pirate paradise. He has children with the princess and starts a new royal family. The King of Madagascar supposedly commanded an army of 15,000 pirates and 40 warships. He was said to live in luxury in a strong fortress. Every even made his own gold coins with his face on them.

Wild rumors about Every had been around for years. But Adrian van Broeck's book created the popular legend of Every. Over time, many English people believed these amazing claims. European governments even received people who claimed to be Every's ambassadors from Saint Mary's. Even leaders started to believe the stories. At one point, English and Scottish officials seriously considered offers from these "pirate diplomats." Peter the Great even tried to hire the Saint Mary's pirates to help build a Russian colony in Madagascar. The idea of a pirate safe haven on Saint Mary's became well-known.

Because he was so famous, Every was one of the few pirates whose life was shown on stage. In 1712, Charles Johnson wrote a play called The Successful Pyrate. It was a mix of tragedy and comedy. It was popular and performed at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane.

In 1720, Every was the main character in Daniel Defoe's The King of Pirates. He also appeared as a small character in Defoe's novel Captain Singleton. Both stories mentioned the widely believed tales of Every's pirate republic. Charles Johnson's famous General History (1724) gave a different account of Every. It said Every was cheated out of his wealth and died poor.

A successful ballad (a song that tells a story) was also printed in England during Every's career. It was called "A Copy of Verses, Composed by Captain Henry Every, Lately Gone to Sea to seek his Fortune." It was first published between May and July 1694. It was supposedly written by Every himself. The ballad had 13 verses. It was later collected by Samuel Pepys.

The ballad mentioned that Every owned land near Plymouth. This was later confirmed by William Philips, a captured crew member. However, it's unlikely Every wrote the verses. It's more likely that one of the loyal sailors who didn't join the mutiny shared what they knew about Every. This information was then quickly turned into a ballad. A slightly changed copy was given to the Privy Council of England in August 1694. It was used as proof during the investigation into the mutiny. The ballad might have been written to help convict Every. In any case, the ballad probably helped the government outlaw Every almost two years before he became the most famous pirate of his time.

During Every's career, the government tried to use the media to show him as a bad criminal. They wanted to change public opinion about piracy. But this attempt mostly failed. Many people continued to feel sympathy for the pirate.

Every's Flag

There are no reliable accounts of Every's pirate flag from his time. The ballad "A Copy of Verses" says Every's flag was red with four gold chevrons. The ballad also suggests green lining the border, but it might have been talking about a shield. Red was a common color for pirate flags then. The meaning of the four chevrons is not clear. It might have been an attempt to link Every to a rich family from the West-Country called Every. Their family crest had different numbers of chevrons. But there is no real proof that Every actually flew such a flag.

Another flag linked to Every shows a white skull wearing a kerchief and an earring. It is above two crossed bones on a black or red background. There is no proof that Every used this flag either. It seems to have been made up for a book in 1959.

Images for kids

-

A steel engraving by Jean Antoine Théodore de Gudin depicting the Battle of Beachy Head, a naval engagement Every likely participated in while serving in the Royal Navy

-

The proclamation for the apprehension of Henry Every, with a reward of £500 sterling (approximately £92294.70 sterling as of November 2023, adjusted for inflation) that was issued by the Privy Council of Scotland on 18 August 1696

-

Avery sells his Jewels, an engraving by Howard Pyle which appeared in the September 1887 issue of Harper's Magazine

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |