Battle of Beachy Head (1690) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Beachy Head |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Nine Years' War | |||||||

An illustration of the battle by Théodore Gudin |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 75 ships 28,000 crewmen |

56 ships 23,000 crewmen |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| No ships lost | 2,350 killed and wounded 4,000 total casualties 7-15 ships captured, sunk or destroyed |

||||||

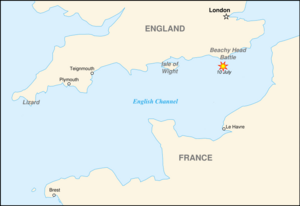

The Battle of Beachy Head, also called the Battle of Bévéziers, was a big naval battle. It happened on July 10, 1690, during a time called the Nine Years' War. This battle was the most important naval win for France against England and the Netherlands in that war.

The Dutch lost several large warships and three 'fireships'. These were old ships filled with flammable materials, used to set enemy ships on fire. Their English friends lost one large warship. But the French didn't lose any ships at all!

France took control of the English Channel for a short time. However, the French Vice-Admiral Anne Hilarion de Tourville didn't chase the English and Dutch fleets very hard. This allowed them to escape to the River Thames. Tourville was later criticized for not finishing the job and lost his command.

The English Admiral Arthur Herbert, 1st Earl of Torrington had warned against fighting the stronger French fleet. But Queen Mary II and her advisors told him to fight anyway. After the battle, Torrington was put on trial for how he acted. Even though he was found innocent, King William III removed him from the navy.

Contents

Why Did the Battle of Beachy Head Happen?

The battle was part of a bigger conflict called the Nine Years' War. This war involved many European countries. A key part of it was about who would rule England. James II of England had been removed from the throne in England. He was trying to get it back, starting with a campaign in Ireland.

King William's Plan for Ireland

In August 1689, a general named Frederick Schomberg went to Ireland. He was there to help King William's forces. But his army struggled through the winter, with many soldiers getting sick or leaving.

By January 1690, King William knew he had to go to Ireland himself. He needed to bring many more soldiers to fix the situation.

The main English and Dutch fleet, led by Admiral Torrington, was in the English Channel. Another part of the English fleet was in the Mediterranean Sea. The English hoped this part of the fleet would keep the French ships in Toulon busy.

A smaller English group of ships was in the Irish Sea. But it was too small to stop the French if they wanted to control those waters. However, the French king, Louis XIV, decided to focus his navy on Torrington's fleet in the Channel instead of helping in Ireland.

French Fleet's Actions

On March 17, 1690, 6,000 French soldiers went to Ireland to help James II. But the main French fleet, led by Comte de Tourville, went back to Brest. They stayed there quietly during May and June while their big fleet gathered.

This quiet period from the French was exactly what King William needed. On June 21, William loaded his soldiers onto 280 transport ships in Chester. Only six warships protected them. On June 24, William landed in Carrickfergus with 15,000 men. The French fleet did not bother him. This was bad news for James II's main leader in Ireland. He later wrote that not having French warships in St George's Channel ruined their plans.

Leading Up to the Battle

The French fleet from Toulon joined Tourville's fleet on June 21. Tourville now had 75 large warships and 23 fireships. On June 23, he sailed into the Channel. By June 30, the French were off the Lizard.

Admiral Torrington sailed from the Nore. He already believed the French would be much stronger. Many English ships were busy protecting trade from pirates. The English and Dutch fleet had only 56 large warships with 4,153 guns. The French fleet had 4,600 guns.

Torrington's Retreat Plan

Torrington's fleet reached the Isle of Wight. There, a Dutch group of 22 ships joined them. This group was led by Cornelis Evertsen. On July 5, Torrington saw the French fleet. He estimated they had almost 80 large warships.

Torrington could not go west to meet other English ships. So, he announced he would retreat from the stronger French fleet. He thought fighting them would be too risky for his entire fleet.

Orders from Queen Mary

While King William was away, Queen Mary and her advisors quickly prepared to defend England. Some advisors thought it was important to fight. They didn't believe the French were as strong as Torrington said. They thought Torrington was just being negative or even disloyal.

As the two fleets slowly moved up the Channel, Torrington carefully stayed out of range. The advisors then sent an order to fight. The orders reached Torrington on July 9, when he was off Beachy Head. Torrington realized that not fighting meant directly disobeying orders. But fighting, in his opinion, meant a high risk of losing. Torrington met with his officers. They decided they had no choice but to obey the order.

The Battle of Beachy Head

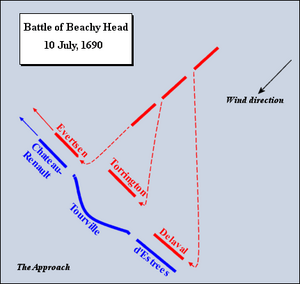

The next day, July 10, off Beachy Head near Eastbourne, Torrington moved his ships forward. He arranged them in a long line ready for battle. He put the Dutch ships, 21 of them, at the front. Torrington was in the middle with his English ships. The ships at the back were a mix of English and Dutch.

The French admiral, Tourville, also divided his 70 warships into three groups. Tourville himself was in the middle group.

Around 8:00 AM, the English and Dutch ships moved forward together. They spread out to cover the entire French fleet. The Dutch ships at the front moved towards the leading French ships. But they left some French ships free. These French ships cut in front of the Dutch and caused a lot of damage.

The English ships in the middle did not help the Dutch enough. Admiral Tourville, seeing he had fewer enemies in the middle, pushed his own leading ships forward. This made the French attack at the front even stronger. The Dutch were now fighting against many more French ships.

The English ships at the back fought a very hard battle against a much larger French force. The Dutch commander, Evertsen, had lost many officers. He was forced to pull back. The Dutch had fought bravely with very little help from the rest of the English and Dutch fleet. They lost two fireships and one large ship that was badly damaged and later burned by the French. Many other Dutch ships were also damaged.

Torrington ended the battle late in the afternoon because his fleet was outmatched. Evertsen saved more Dutch ships by using the tide and the dropping wind. He ordered his ships to drop their anchors while still sailing. The French, who were not quick enough, were carried away by the current and out of firing range.

The eight-hour battle was a French victory, but it wasn't a complete defeat for the English and Dutch. When the tide changed at 9:00 PM, the English and Dutch ships raised their anchors. Tourville chased them, but he kept his ships in a strict line. This made his fleet move at the speed of the slowest ships.

Torrington burned six more badly damaged Dutch ships and one English ship to stop the French from capturing them. Another Dutch ship sank on its own. As soon as Torrington reached the safety of the River Thames, he ordered all the navigation buoys removed. This made it too dangerous for the French to follow him.

What Happened After the Battle?

The defeat at Beachy Head caused great fear in England. Tourville now had temporary control of the English Channel. It seemed like the French could stop King William from returning from Ireland. They could also land an invading army in England.

People were very worried. One writer, John Evelyn, wrote that the whole country was scared because the French fleet was so close to the mouth of the Thames. This fear grew when news arrived of another French victory on land. To prepare for a possible invasion, 6,000 soldiers and quickly organized local militias were made ready to defend the country.

Blame and Consequences

In this time of fear, no one blamed the defeat on the French having more ships. The Dutch commander, Evertsen, said that Torrington had purposely left the Dutch ships alone. An English advisor accused Torrington of disloyalty. He told King William that Torrington had abandoned the Dutch so badly that their whole group of ships would have been lost if some English ships hadn't saved them.

King William was very upset. He wrote to a Dutch leader, saying how distressed he was about the fleet's problems. He was especially upset because he heard his ships didn't properly support the Dutch.

French Missed Opportunity

There was some good news for the English and Dutch. The day after Beachy Head, July 11, King William won a big victory in Ireland. He defeated James II at the Battle of the Boyne. James fled to France, but his requests for an invasion of England were not followed.

The French naval minister had not planned for an invasion. He had only thought as far as the battle itself. He wrote to Tourville before the battle, saying he just wanted to know what Tourville planned to do with the fleet afterward. Tourville anchored his ships to repair them and land his sick sailors. The French had failed to use their victory to their full advantage.

To the anger of King Louis and his minister, the only real result of Tourville's victory was the burning of the English coastal town of Teignmouth in July. Tourville was then removed from his command.

Torrington's Trial

The English ships gathered back with the main fleet. By the end of August, the English and Dutch had 90 ships sailing the Channel. The French control of the Channel was over.

Torrington was sent to the Tower of London to await a trial in Chatham. He was accused of retreating and not doing his best to harm the enemy or help his own and the Dutch ships. Torrington argued that the defeat was due to a lack of preparation and information. He said he hadn't been told that the French fleet had been made stronger. He also claimed the Dutch had attacked too early.

To the surprise of King William and his advisors, Torrington was found innocent. This pleased the English sailors, who felt he was being unfairly blamed. Torrington went back to his seat in the House of Lords. But King William refused to see him and removed him from the navy on December 12. Torrington was temporarily replaced by three admirals, who were later replaced by Admiral Russell as the sole commander of the English fleet.

Images for kids

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |