Alexander Bain (inventor) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alexander Bain

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 12 October 1810 |

| Died | 2 January 1877 (aged 66) Broomhill, Kirkintilloch, Scotland

|

| Resting place | Auld Aisle Cemetery, Kirkintilloch, Scotland |

| Occupation | instrument inventor, technician, and clockmaker |

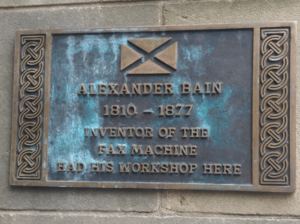

Alexander Bain (born October 12, 1810 – died January 2, 1877) was a clever Scottish inventor and engineer. He was the first person to invent and get a patent for the electric clock. He also helped set up the very first telegraph lines for railways between Edinburgh and Glasgow in Scotland.

Contents

Early Life of Alexander Bain

Alexander Bain was born in a small place called Leanmore, near Watten, in Caithness, Scotland. He was baptized in the local church in November 1810. His father was a crofter, which means he was a small farmer who rented land.

Alexander had a twin sister named Margaret, and a total of six sisters and six brothers. He wasn't the best student in school. When he was older, he became an apprentice to a clockmaker in Wick. This means he learned the skill of making clocks by working for an experienced clockmaker.

Bain's Career and Inventions

After learning how to make clocks, Alexander Bain moved to Edinburgh. In 1837, he moved to London. There, he worked as a journeyman, which is a skilled worker who has finished an apprenticeship. He often went to lectures at places like the Polytechnic Institution. Later, he opened his own workshop.

Inventing Electric Clocks and Telegraphs

In 1840, Bain needed money to develop his new inventions. He talked to the editor of a magazine who introduced him to Sir Charles Wheatstone, another inventor. Bain showed Wheatstone his ideas for electric clocks. Wheatstone told him not to bother, saying there was "no future in them."

However, just three months later, Wheatstone showed an electric clock to the Royal Society. He claimed it was his own idea! But Bain had already applied for a patent for his electric clock. A patent is a special right that protects an invention. Wheatstone tried to stop Bain's patents, but he failed.

Later, when Wheatstone helped create a company called the Electric Telegraph Company, the government asked Bain to share his story. In the end, the company had to pay Bain £10,000 (a lot of money back then!) and give him a job as a manager. This made Wheatstone resign.

Bain's first patent for an electric clock was in January 1841. His clock used a pendulum that was kept swinging by electromagnetic pushes. He later improved his designs. He even suggested getting electricity from an "earth battery," which used metal plates buried in the ground.

In December 1841, Bain also patented a way to use electricity to control railway engines. This included turning off steam, keeping time, sending signals, and printing information. He also improved the needle telegraph. Instead of a moving needle, he used a coil that moved between magnets.

Bain's telegraph was first used in December 1845 on the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway. It was also used on the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1846. These telegraphs worked well and were even used in other countries like Austria.

"For many years I have devoted myself to rendering electricity practically useful, and have been extensively engaged, not only in this country, but in America and on the Continent, in the construction and working of the Electric Telegraph; while at the same time, the employment of electricity in the measurement of time has also engaged my attention."

Alexander Bain, A Short History of the Electric Clocks

Bain's Surviving Inventions

You can still see some of Bain's electric clocks today. They are in places like the National Museum of Scotland, the National Maritime Museum in London, and the Deutsches Uhrenmuseum in Germany. Some special mantel clocks are also owned by private collectors.

Bain sometimes created very complex solutions for problems. His mantel clock used a complicated electromagnetic system to keep the pendulum swinging. Around the same time, another inventor named Matthäus Hipp created a simpler and more reliable system.

One of Bain's telegraph machines is on display at the National Museum of Scotland. It was likely used on the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway. Two other telegraphs used at the Shildon tunnel are in the National Railway Museum. There's also one of his printing telegraphs from 1843 in the Museum für Kommunikation Frankfurt.

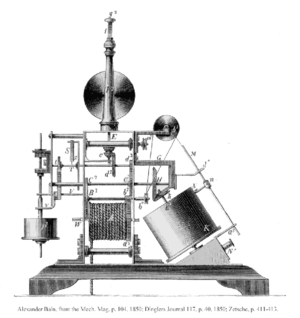

Developing the Facsimile Machine

From 1843 to 1846, Bain worked on an early version of a fax machine. A fax machine sends images or documents over a distance. He used clocks to make sure two pendulums moved together, scanning a message line by line.

To send a message, Bain used metal pins on a cylinder made of material that didn't conduct electricity. An electric probe scanned these pins, sending on-off electrical pulses. At the other end, the message was printed on special paper that changed color when electricity passed through it.

Bain's early fax machines were not perfect. The sending and receiving machines often didn't stay perfectly in sync. In 1861, the first truly practical fax machine, called the Pantelegraph, was invented by Giovanni Caselli. He started the first commercial fax service between Paris and Lyon.

The Chemical Telegraph

In December 1846, Bain patented his "chemical telegraph." He noticed that the Morse telegraphs of his time were slow because they had many moving parts. Bain realized he could use an electric current to make a mark directly on a moving paper tape.

He used paper soaked in a special chemical mixture. When electricity passed through it, it made a blue mark. This method was much faster! It was so fast that people couldn't send signals by hand quickly enough. So, Bain invented a way to send signals automatically using punched paper tape. This idea was later used by other inventors.

Bain's chemical telegraph was tested between Paris and Lille. It could send 282 words in just 52 seconds! This was a huge improvement over Morse's telegraph, which could only send about 40 words per minute.

In England, Bain's telegraph was used a little bit. In America, it was used by Henry O'Reilly. However, Samuel Morse (the inventor of Morse code) didn't like it. He got a court order against Bain, saying that Bain's paper tape and alphabet were too similar to his own patent. Because of this, Bain's telegraph was not widely used.

Later Life and Legacy

Alexander Bain made a good amount of money from his inventions at first. But he lost his wealth because of bad investments. In 1873, some important people, including Sir William Thomson, helped him get a special pension of £80 per year from the Prime Minister.

Death and Legacy

Alexander Bain was buried in the Auld Aisle Cemetery in Kirkintilloch. His gravestone was fixed in 1959 because it initially had the wrong year of death.

Today, a pub in Wick, near where Bain learned clockmaking, is named 'The Alexander Bain' in his honor. Also, the main BT building in Glasgow is called Alexander Bain House, celebrating his inventions. One of his early electric pendulum clocks is on display at the Deutsches Uhrenmuseum.

In 2016, Alexander Bain was given a special award after his death: the Technology & Engineering Emmy Award. This was "for his pioneering work in the transmission of images" (like his early fax machine). The award statue is now in Kirkintilloch Town Hall.

Patents

- U.S. Patent 006,837

Images for kids

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |