Robert Stephenson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Robert Stephenson

|

|

|---|---|

Stephenson in 1856

|

|

| Born | 16 October 1803 Willington Quay, Northumberland, England

|

| Died | 12 October 1859 (aged 55) London, England

|

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Spouse(s) | Frances Sanderson (m. 1829–1842; her death) |

| Parent(s) | George Stephenson |

| Relatives | George Robert Stephenson (cousin) |

| Engineering career | |

| Projects |

|

| Awards | |

Robert Stephenson (born October 16, 1803 – died October 12, 1859) was a famous English civil engineer. He was also a brilliant designer of locomotives, which are train engines. Robert was the only son of George Stephenson, who is known as the "Father of Railways." Robert continued his father's amazing work. Many people believe Robert was the greatest engineer of the 1800s.

Contents

Robert Stephenson's Life and Work

By 1850, Robert Stephenson had helped build a huge part of Britain's railway system. He designed important bridges like the High Level Bridge and the Royal Border Bridge. These bridges were part of the East Coast Main Line.

He worked with other engineers to create strong bridges made of wrought-iron tubes. A famous example is the Britannia Bridge in Wales. He later used this design for the Victoria Bridge in Montreal, Canada. For many years, this was the longest bridge in the world! Robert worked on 160 projects for 60 different companies. He even built railways in other countries like Belgium, Norway, Egypt, and France.

In 1829, Robert married Frances Sanderson. They did not have any children. After Frances died in 1842, Robert never married again. In 1847, he became a Member of Parliament (MP) for Whitby. He kept this job until he died.

Robert was offered a special award called a knighthood in Britain, but he said no. However, he received honors from other countries. He was made a Knight of the Order of Leopold in Belgium. He also became a Knight of the Legion of Honour in France. In Norway, he was given the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St. Olaf. In 1849, he became a Fellow of the Royal Society. He also led important engineering groups like the Institution of Mechanical Engineers and the Institution of Civil Engineers.

When Robert Stephenson died, many people were very sad. His funeral procession was allowed to go through Hyde Park. This was a special honor usually only given to royalty. He is buried in Westminster Abbey.

Early Life and Education

Robert Stephenson was born on October 16, 1803. His birthplace was Willington Quay, near Newcastle upon Tyne. His parents were George Stephenson and Frances Henderson. His mother, Fanny, passed away when Robert was young.

Robert first went to a small village school. His father, George, had not received much formal education. But George wanted his son to have a good one. So, he sent 11-year-old Robert to the Percy Street Academy in Newcastle. Robert joined the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society. He borrowed many books for himself and his father to read. In the evenings, he and his father worked on designs for steam engines. In 1816, they even built a sundial together. You can still see it above their cottage door today.

After school in 1819, Robert became an apprentice to a mining engineer named Nicholas Wood. This was at Killingworth colliery. Robert worked very hard. He couldn't afford a special mining compass, so he made one himself. He later used this compass to survey the High Level Bridge in Newcastle.

Building the Stockton and Darlington Railway

In the early 1800s, people needed ways to move coal from mines to ports. Canals were suggested, but a tramway was also an idea. In 1821, a law was passed to build the Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR). Edward Pease and George Stephenson met and George was hired to survey the railway line.

Robert was still an apprentice, but he helped his father with the survey. They found a good route for the railway. George Stephenson believed in using steam locomotives. The railway directors visited a colliery where George had already introduced locomotives. George also wanted Robert to get a university education. So, Robert went to Edinburgh University for a short time in 1822-1823.

In 1823, a new law allowed the S&DR to use "loco-motives or moveable engines." In June 1823, the Stephensons and Pease started a company called Robert Stephenson and Company in Newcastle. Their goal was to build these locomotives. Robert was put in charge of the works. He also designed a branch line for the railway. The S&DR ordered steam locomotives from their company. The railway officially opened on September 27, 1825.

Adventures in Colombian Mines

In 1824, Robert Stephenson sailed to South America for a three-year contract. He went to Gran Colombia, which is now Colombia and Venezuela. British investors were interested in reopening old gold and silver mines there. Robert Stephenson & Co. received orders for steam engines for these mines.

Robert learned Spanish and visited mines in England to prepare. He arrived in Venezuela in July 1824. He looked into building a breakwater and a pier at the harbor. He also considered a railway to Caracas. Caracas is very high up, almost 1,000 meters above sea level. Building a railway there was a huge challenge. Robert decided that a railway would be too expensive.

He traveled to Bogotá and then to the mines. The heavy equipment couldn't reach the mines because the paths were too narrow and steep. Robert set up his home in a bungalow at Santa Ana. Miners from Cornwall came to work, but they were difficult to manage.

Robert's contract ended in 1827. He tried to cross the Panama Isthmus, but it was too hard. While waiting for a ship, he met Richard Trevithick, another railway pioneer. Trevithick had been searching for gold and silver in South America. Robert gave him £50 to help him get home.

Robert then sailed to New York. His ship sank in a storm, and he lost his money and luggage. He noticed that a second-class passenger was saved before first-class passengers. The captain explained they were Freemasons and had sworn to help each other in danger. Robert was impressed and became a Freemason in New York. He then walked 500 miles to Montreal to see more of North America. Finally, he returned to Liverpool in November 1827.

Becoming a Locomotive Designer

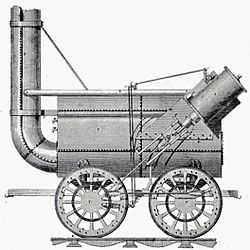

When Robert returned, his father George was the chief engineer for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR). George had built a locomotive called Experiment. Robert wanted to make train wheels work better. He got his chance in 1828 when the L&MR ordered a new locomotive.

The Lancashire Witch was built with angled cylinders. This allowed the axles to have springs, making the ride smoother. Robert also surveyed routes for new railways and advised on a tunnel under the River Mersey.

In 1828, Robert wrote about his feelings for Frances Sanderson. They had known each other before he went to South America. He visited her often after he returned. She accepted his marriage proposal. Robert and Fanny married in London on June 17, 1829. They moved into a house in Newcastle.

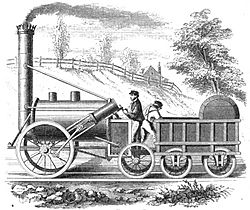

The L&MR directors needed to decide if they would use stationary engines with ropes or steam locomotives. They decided to hold trials to test steam locomotives. These trials took place at Rainhill on a two-mile railway. Robert designed the locomotive for these trials in the summer of 1829. He used a new idea to heat water in the boiler using many small tubes. This made the engine much more powerful. In September, the Rocket locomotive was sent to Rainhill.

The Rainhill trials began on October 6. Between 10,000 and 15,000 people came to watch! Five locomotives arrived. Rocket competed against Novelty and Sans Pareil. On October 8, Rocket started its 70-mile journey. It ran back and forth across the course. It reached a top speed of over 29 miles per hour! Rocket was declared the winner.

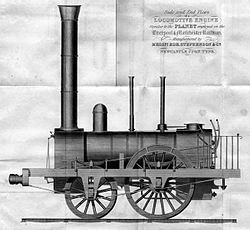

The L&MR bought Rocket and ordered more locomotives from Robert Stephenson & Co. Soon, they delivered Planet in 1830. This new design had cylinders placed horizontally under the boiler. Many orders for locomotives came in. In 1831, Stephenson suggested opening a second locomotive factory. This factory became the Vulcan Foundry.

Becoming a Civil Engineer

Early Railway Projects

In 1824, George Stephenson & Son was formed to survey and build railways. Both George and Robert were chief engineers. Robert took charge of building the Canterbury and Whitstable Railway. It opened in 1830 with a locomotive similar to Rocket called Invicta. He also worked on other railway lines, like the Bolton & Leigh Railway.

The London and Birmingham Railway

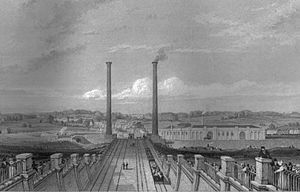

In 1830, George Stephenson & Son began surveying the route for the London and Birmingham Railway. Robert did most of the work. He joined the Institution of Civil Engineers that same year. The railway plans faced opposition from landowners. Robert defended the plans in Parliament. After more surveys, the necessary law was passed on May 6, 1833. Robert, who was not yet 30, signed the contract to build the 112-mile railway from Camden Town to Birmingham.

Robert earned a good salary for this project. He and Fanny moved from Newcastle to London. He made detailed plans and divided the line into 30 sections. He set up an office with many draughtsmen. Some parts of the line, like the Primrose Hill Tunnel and Kilsby Tunnel, had engineering problems. These were completed using direct labor.

The railway line ended north of Regent's Canal at Camden. This was because a landowner had opposed the railway. Later, the landowner changed his mind. So, they got permission to extend the line south to Euston Square. This part of the line had a steep slope. Trains from Euston were pulled up by a rope. This was due to a rule in the railway law, not because locomotives weren't powerful enough.

The London and Birmingham Railway officially opened on September 15, 1838. It took four years and three months to build. It cost £5.5 million, which was more than the original estimate.

New Challenges and Personal Loss

In 1835, Robert traveled with his father to Belgium. George was asked to advise the King of Belgium on their state railway. Robert returned two years later to celebrate the railway's opening. Robert was very busy with the London and Birmingham Railway. But he was allowed to work as a consultant on other projects.

In 1842, Stephenson employees in Newcastle developed the Stephenson valve gear. This was an important improvement for locomotives. Robert also worked on the Stanhope and Tyne Railway. This company had financial problems. Robert helped create a new company, the Pontop and South Shields Railway, to take over the line. He even contributed £20,000 of his own money.

Robert traveled a lot, visiting France, Spain, and Italy to advise on railways. He was often asked to settle disagreements between railway companies. In August 1841, he was made Knight of the Order of Leopold for his work on locomotives.

In 1842, Robert's wife, Fanny, became very ill with cancer. She died on October 4, 1842. She wanted Robert to remarry and have children, but he remained single for the rest of his life. Robert returned to work soon after her funeral, but he visited her grave for many years.

The Gauge Wars and Bridge Building

Robert moved to Cambridge Square in Westminster after his wife's death. He often socialized at clubs in London. By 1850, Robert had helped build a third of Britain's railways. He was working very hard and became ill.

When George Stephenson built the Stockton & Darlington and Liverpool & Manchester railways, he set the rails 4 feet 8.5 inches apart. This became the standard gauge. However, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, another famous engineer, used a wider gauge of 7 feet for his Great Western Railway. He believed this would allow for faster trains.

In 1844, railways with different gauges met for the first time at Gloucester. This caused problems for goods and passengers. A special commission was set up to decide on a standard gauge. Robert supported the standard gauge. The commissioners decided in favor of the 4 foot 8.5 inch gauge, mainly because so many miles of track were already laid with it.

Robert's stepmother died in 1845. His father, George, retired and died in 1848. Robert then took over as President of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers until 1853.

Building Famous Bridges

In 1845, Robert became the chief engineer for the Chester & Holyhead Railway. He designed an iron bridge to cross the River Dee near Chester. In May 1847, the bridge collapsed under a passenger train. Five people died. Robert was very upset. He never used long cast-iron girders again. A Royal Commission was later set up to study the use of cast iron in railways.

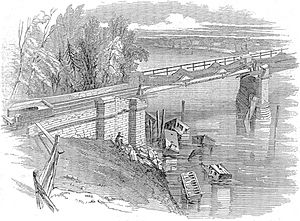

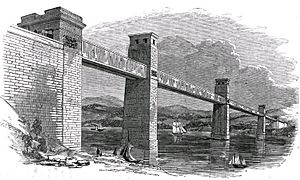

The Britannia Bridge was built for the Chester & Holyhead Railway. It needed to cross the Menai Strait to the island of Anglesey. The Admiralty (the navy) insisted on a single span 100 feet above the water. Robert, with William Fairbairn and Eaton Hodgkinson, designed a new type of bridge. It was a wrought-iron tubular bridge, large enough for a train to pass through.

They tested models and decided to use a similar design for the Conwy Railway Bridge first. The first tube for the Conwy Bridge was put in place in March 1848. The Britannia Bridge had four tubes. The first tube for the Britannia Bridge was put in place in June 1849. The bridge opened for a single line of traffic in March 1850. The second line opened in October.

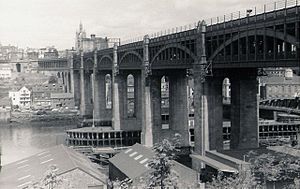

Robert also worked on the railway route north of Newcastle to Edinburgh. This included two major bridges. The High Level Bridge in Newcastle is 1,372 feet long and 146 feet high. It is made of cast-iron arches with wrought-iron ties. Queen Victoria formally opened it in September 1849. Robert had just become a Fellow of the Royal Society in June.

The Royal Border Bridge across the Tweed is a stone viaduct with 28 arches. The Queen opened this bridge on August 29, 1850. At the celebration dinner, Robert sat next to the Queen. He had just been offered a knighthood, but he had politely declined it.

Robert Stephenson in Politics

In 1847, Robert was asked to run for Member of Parliament (MP) for Whitby. He was elected without anyone running against him. He remained the MP for Whitby for the rest of his life. He was a member of the Conservative Party. He supported protecting local industries and opposed free trade.

His first speech in Parliament was in favor of the Great Exhibition. He became one of the Commissioners for this big event. Robert spoke against some educational reforms. He believed workmen only needed to learn skills for their jobs. However, he did donate money to educational groups.

Robert also became a member of a French group studying the Suez canal. He traveled to look at the canal's feasibility. He advised against building a canal, saying it would fill with sand. Instead, he helped build a railway between Alexandria and Cairo in Egypt. This railway opened in 1854. He spoke in Parliament against the Suez Canal plan in 1857 and 1858.

Later Life and Legacy

Robert moved to 34 Gloucester Square in 1847. He often socialized at clubs in London. By 1850, Robert was involved in a third of Britain's railway system. He was working too hard and became ill with a kidney disease.

Inventors and promoters often bothered Robert. To get away from them, he bought a 100-ton yacht in 1850. He called her Titania. He called his yacht "the house that has no knocker" because he had no unwanted visitors when he was on board. He seemed to become younger and more excited when he was on his yacht. He joined the Royal Yacht Squadron in 1850. His yacht, Titania, lost a race to the famous yacht America a few days later. A second, larger yacht, also named Titania, was built in 1852 after the first one was destroyed by fire.

In 1850, Robert became chief engineer for the Norwegian Trunk Railway from Oslo to Lake Mjøsa. He visited Norway several times for this project. In 1852, Robert traveled to Canada. He advised the Grand Trunk Railway on crossing the St Lawrence River at Montreal. The Victoria Bridge was 8,600 feet long. It had 25 wrought iron sections. For a time, it was the longest bridge in the world.

In 1855, Robert was awarded the Knight of the Legion of Honour by the Emperor of France. He became president of the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1856. The next year, he received an honorary degree from Oxford University.

Robert was close friends with other famous engineers like Brunel and Locke. In 1857, even though he was weak, he helped Brunel launch the huge ship SS Great Eastern. Robert fell into the mud but kept working. The next day, he was sick in bed for two weeks.

In late 1858, Robert sailed to Alexandria. He spent time on his yacht or at a hotel in Cairo. He had Christmas dinner with his friend Brunel. He returned to London in February 1859. He was ill that summer. He sailed to Oslo to celebrate the opening of the Norwegian Trunk railway. He also received the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St. Olaf. He became very ill at the banquet on September 3. He returned to England on his yacht, but the journey was long due to a storm. As Robert landed, Brunel was already very ill and died the next day. Robert got a little better, but he died on October 12, 1859.

Robert Stephenson's Legacy

Robert's death was deeply felt across the country. It happened just a few days after Brunel's death. His funeral procession was allowed to pass through Hyde Park, a special honor. Two thousand tickets were given out for his service at Westminster Abbey. He was buried next to the famous civil engineer Thomas Telford. Ships on rivers like the Thames and Tyne lowered their flags to half-mast. Work stopped at midday in Tyneside. The 1,500 employees of Robert Stephenson & Co. marched through Newcastle for their own memorial service.

Robert left about £400,000. He left his Newcastle locomotive works and some collieries to his cousin, George Robert Stephenson. He also left money to friends and institutions, including the Newcastle Infirmary. One gift of £2,000 went to a fund for the North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers. Robert was a member of this institute.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Robert Stephenson para niños

In Spanish: Robert Stephenson para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |