Richard Trevithick facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Richard Trevithick

|

|

|---|---|

1816 Portrait by John Linnell.

Science Museum, London |

|

| Born | 13 April 1771 Tregajorran, Cornwall, England

|

| Died | 22 April 1833 (aged 62) |

| Nationality | British |

| Known for | Steam locomotives |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Inventor, mining engineer |

Richard Trevithick (born April 13, 1771 – died April 22, 1833) was a brilliant British inventor and mining engineer. He grew up in the heart of Cornwall, a place famous for its mines. His father was a mining captain, so Richard was surrounded by engineering from a young age.

Trevithick was a pioneer in using steam power for both roads and railways. His biggest achievements were creating the first high-pressure steam engine and the first working railway steam locomotive. On February 21, 1804, his steam locomotive made history. It pulled a train along the tramway at the Penydarren Ironworks in Merthyr Tydfil, Wales. This was the world's first journey by a locomotive-hauled train!

Richard Trevithick also worked as a mining expert in Peru and explored parts of Costa Rica. He faced many challenges, including money problems and strong competition from other engineers. Even though he was well-known and respected for much of his career, he became less famous towards the end of his life. Trevithick was also incredibly strong and a champion Cornish wrestler.

Contents

Richard Trevithick's Early Life

Richard Trevithick was born in Tregajorran, a village in Cornwall. This area was rich in minerals and had many mines. He was the youngest boy in a family of six children. Richard was very tall for his time, standing at 6 feet 2 inches. He was also very athletic and preferred sports over schoolwork.

He went to the village school in Camborne. However, he wasn't very interested in his studies. One teacher even called him "a disobedient, slow, obstinate, spoiled boy." But Richard was good at arithmetic, even if he found his own ways to solve problems.

Richard's father was also named Richard Trevithick and was a mine captain. His mother, Ann Teague, was a miner's daughter. As a child, Richard watched steam engines pump water out of deep tin and copper mines in Cornwall. He also lived near William Murdoch, who was experimenting with steam-powered road vehicles. These early experiences likely sparked Richard's interest in steam power.

At 19, Trevithick started working at the East Stray Park Mine. He quickly became a consultant, which was unusual for someone so young. Miners liked him because they respected his father.

Family Life and Marriage

In 1797, Richard Trevithick married Jane Harvey from Hayle. They had six children:

- Richard Trevithick (1798–1872)

- Anne Ellis (1800–1877)

- Elizabeth Banfield (1803–1870)

- John Harvey Trevithick (1807–1877)

- Francis Trevithick (1812–1877)

- Frederick Henry Trevithick (1816–1883)

Developing the High-Pressure Steam Engine

Jane's father, John Harvey, owned a famous foundry called Harveys of Hayle. His company built huge stationary "beam" engines. These engines were used to pump water, especially from mines. At that time, most steam engines were low-pressure, like those invented by Thomas Newcomen. James Watt later improved these engines, and his patents made it difficult for others to build similar machines without paying him.

In 1797, Trevithick became an engineer at the Ding Dong Mine. Here, he worked with Edward Bull to develop high-pressure steam engines. He wanted to build engines that didn't need to pay royalties to Watt. Because of this, Boulton & Watt even tried to stop him with a legal order.

Trevithick realized that new boiler technology could safely create high-pressure steam. This steam could directly push a piston in an engine. This was different from older engines that used pressure close to the air around them.

He wasn't the first to think of "strong steam." William Murdoch had shown a model steam carriage in 1784. Trevithick even saw Murdoch's demonstration in 1794. However, Trevithick was the first to make high-pressure steam work in England in 1799. A high-pressure engine didn't need a separate condenser, making it smaller and lighter. This meant an engine could be small enough to move itself, even with a carriage attached.

Early Experiments with Steam Power

Trevithick started by building small models of high-pressure steam engines. First, he made a stationary one, then one attached to a road carriage. His engines used a double-acting cylinder. Steam was released into the air through a vertical pipe or chimney. This avoided using a condenser and any patent issues with Watt. The engine's straight motion was turned into circular motion using a crank, which was simpler than older designs.

Puffing Devil and Road Locomotives

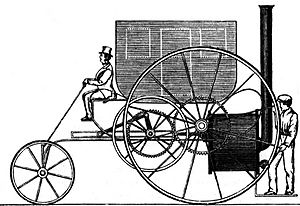

In 1801, Trevithick built a full-size steam road locomotive near Camborne. He called it the Puffing Devil. On Christmas Eve that year, he showed it off. It successfully carried six passengers up Fore Street and then up Camborne Hill to the village of Beacon. His cousin, Andrew Vivian, steered the machine. This event inspired the famous Cornish folk song "Camborne Hill".

A few days later, during more tests, the Puffing Devil broke down. The operators left it with the fire still burning while they went for a meal. The water in the boiler boiled away, the engine got too hot, and the machine burned. Trevithick saw this as a mistake by the operators, not a problem with his design.

In 1802, Trevithick got a patent for his high-pressure steam engine. To prove how well it worked, he built a stationary engine at the Coalbrookdale Company in Shropshire. This engine ran at 40 piston strokes a minute, with a very high boiler pressure of 145 psi.

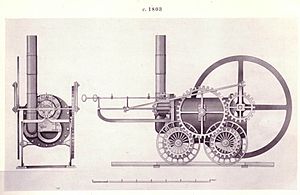

The Coalbrookdale Locomotive

The Coalbrookdale Company built a rail locomotive for Trevithick in 1802. We don't know much about it, or if it ever ran. A worker died in an accident involving the engine, which might have stopped the company from using it on their railway. The only information we have is from a drawing at the Science Museum, London. This drawing shows a single horizontal cylinder inside a boiler. A flywheel turned the wheels on one side using gears. The axles were attached directly to the boiler.

London Steam Carriage

In 1803, Trevithick built another steam-powered road vehicle, called the London Steam Carriage. He drove it in London from Holborn to Paddington and back. Many people were curious about it. However, it wasn't comfortable for passengers and cost more to run than horse-drawn carriages. So, it was eventually stopped.

Tragedy at Greenwich

Also in 1803, one of Trevithick's stationary pumping engines exploded in Greenwich, killing four men. Trevithick believed it was due to careless use, not a design flaw. But his rivals, James Watt and Matthew Boulton, used this accident to highlight the dangers of high-pressure steam.

To make his engines safer, Trevithick added two safety valves to his future designs. Only one could be adjusted by the operator. He also added a fusible plug made of lead. If the water level in the boiler got too low, the lead would melt, releasing steam and making a noise. This warned the operator to cool the boiler before damage occurred. He also started testing boilers with water pressure and used a mercury manometer to show the pressure.

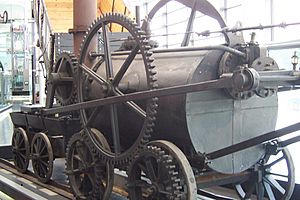

"Pen-y-Darren" Locomotive: A World First

In 1802, Trevithick built a high-pressure steam engine for the Penydarren Ironworks in Merthyr Tydfil, Wales. With help from Rees Jones and under the eye of Samuel Homfray, the owner, he put the engine on wheels to create a locomotive. In 1803, Trevithick sold the patents for his locomotives to Homfray.

Homfray was so impressed that he made a bet with another ironmaster, Richard Crawshay. He bet 500 guineas that Trevithick's locomotive could pull ten tons of iron along the Merthyr Tramroad. This was a distance of about 9.75 miles (15.7 km) from Penydarren to Abercynon.

On February 21, 1804, with many people watching, the locomotive succeeded! It carried 10 tons of iron, 5 wagons, and 70 men the whole distance in 4 hours and 5 minutes. This was an average speed of about 2.4 miles per hour (3.9 km/h).

The locomotive had a boiler with a single flue and four wheels. A single cylinder was partly inside the boiler. It had a large flywheel on one side to make the movement smooth. This movement was sent to a central cog-wheel that connected to the driving wheels. The exhaust steam went up the chimney, which helped the fire burn better and made the engine more efficient.

Trevithick won the bet! He showed that heavy carriages could be pulled along iron tracks using a steam locomotive's weight. However, the cast iron plates of the tramroad broke under the locomotive's weight. They were only made for lighter, horse-drawn wagons. So, the tramroad went back to using horses after this test.

Homfray was happy he won his bet. The engine was then used for its original job of driving hammers. Today, a full-scale working model of the Pen-y-Darren locomotive is at the National Waterfront Museum in Swansea.

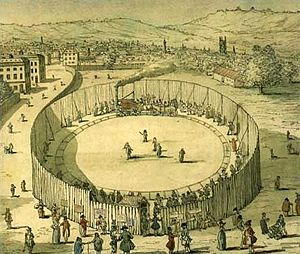

"Catch Me Who Can" Locomotive

In 1808, Trevithick built a new locomotive called Catch Me Who Can. It was built by John Hazledine and John Urpeth Rastrick in Bridgnorth. He ran it on a circular track in London, near where Euston Square tube station is today.

People could pay one shilling to ride the "steam circus." Trevithick wanted to show that rail travel was faster than horses. But the tracks were weak, and not many people were interested.

Trevithick was disappointed and stopped designing railway locomotives. It wasn't until 1812 that twin-cylinder steam locomotives, built by Matthew Murray, successfully replaced horses for pulling coal wagons.

Other Engineering Projects

Thames Tunnel Challenges

In 1805, another engineer, Robert Vazie, started digging a tunnel under the River Thames at Rotherhithe. He faced big problems with water flooding the tunnel. Trevithick was called in to help. The company promised him £1000 if he could finish the tunnel, which was 1220 feet (372 meters) long.

In August 1807, Trevithick started digging a smaller pilot tunnel. By December, after digging 950 feet (290 meters), water rushed in. A month later, in January 1808, at 1040 feet (317 meters), an even worse flood happened. The tunnel was completely flooded, and Trevithick almost drowned. Even though clay was used to seal the hole, digging became very hard. The project stopped, and Trevithick's connection with the company ended.

The first successful tunnel under the Thames was started later in 1823 by Sir Marc Isambard Brunel. He finally finished it in 1843. Trevithick's idea of a submerged tube for tunnels was used much later. For example, the Michigan Central Railway Tunnel in the US and Canada, finished in 1910, used this method.

Return to London and New Ideas

Trevithick continued to explore new uses for his high-pressure steam engines. He thought about using them for boring brass for cannons, crushing stone, and powering mills and hammers. He also built a barge with paddle wheels and several dredgers.

In 1808, he moved his family to London for two and a half years. He partnered with Robert Dickinson (businessman), a merchant. Dickinson supported some of Trevithick's patents. One idea was the Nautical Labourer, a steam tugboat with a floating crane. But it didn't meet safety rules for the docks.

Another idea was to use iron tanks in ships to store cargo and water instead of wooden casks. He set up a small workshop to make them. These tanks were also used to raise sunken wrecks by filling them with air to make them float. In 1810, he raised a wreck near Margate this way.

In 1809, Trevithick worked on many ideas for ships. These included iron floating docks, iron ships, and using heat from ship boilers for cooking.

Health and Financial Troubles

In May 1810, Trevithick became very ill with typhoid. By September, he was well enough to travel back to Cornwall. In February 1811, he and Dickinson were declared bankrupt. Trevithick paid off most of the debts himself.

The Cornish Boiler and Engine

Around 1812, Trevithick designed the ‘Cornish boiler’. These were horizontal, cylindrical boilers with a single internal fire tube. Hot gases from the fire passed through this tube, heating the water more efficiently. These boilers greatly improved the efficiency of pumping engines in mines.

Also in 1812, he installed a new 'high-pressure' steam engine at Wheal Prosper. This became known as the Cornish engine. It was the most efficient engine in the world at that time. Other engineers helped develop it, but Trevithick's work was key. He also installed a high-pressure engine in a threshing machine on a farm. It worked very well and was cheaper than using horses. This engine was used for 70 years and is now at the Science Museum.

Adventures in South America

Draining Silver Mines in Peru

In 1811, the rich silver mines of Cerro de Pasco in Peru had a big problem: water. The mines were very high up, at 4330 meters (14,206 feet). Old low-pressure engines didn't work well at this altitude. Also, they were too big to transport along the narrow mule tracks.

A man named Francisco Uville was sent to England to find a solution. He bought one of Trevithick's high-pressure steam engines. He took it back to Peru, and it worked very well. In 1813, Uville sailed to England again. By chance, he met one of Trevithick's cousins on the ship. This led to Uville meeting Trevithick and telling him about the mining project.

Trevithick Goes to South America

On October 20, 1816, Trevithick left England for Peru. He was first welcomed by Uville, but their relationship soon turned sour. Trevithick then traveled widely in Peru, advising on mining methods. He found new mining areas but didn't have enough money to develop them himself. He did work on a copper and silver mine at Caxatambo.

Later, he served in the army of Simon Bolivar. He returned to Caxatambo, but the country was unstable due to war. He had to leave the area and abandon £5,000 worth of ore. Back in England, people criticized him for neglecting his family.

Exploring Costa Rica on Foot

After leaving Peru, Trevithick traveled through Ecuador to Bogotá in Colombia. In 1822, he arrived in Costa Rica, hoping to develop mining machinery. He looked for a good way to transport ore and equipment. He thought about using the San Juan River, the Sarapiqui River, and then building a railway.

His journey was very dangerous. One person in his group drowned, and Trevithick himself almost died twice. Once, he was saved from drowning. Another time, he was nearly attacked by an alligator. Still with his companion, James Gerard, he made his way to Cartagena. There, he met Robert Stephenson, who was returning home from his own mining venture. Stephenson, who had not seen Trevithick since he was a baby, gave him £50 to help him get home. Trevithick sailed directly to Falmouth, arriving in October 1827 with almost nothing. He never returned to Costa Rica.

Later Years and Legacy

Final Projects

Trevithick asked the British Parliament for money, but he didn't get any. In 1829, he built a new type of steam engine and a vertical boiler. In 1830, he invented an early form of storage heater. It was a small boiler that could be heated and then wheeled to where heat was needed.

In 1832, he designed a huge column to celebrate the Reform Bill. It was meant to be 1000 feet (305 meters) high and made of cast iron. Many people were interested, but it was never built.

Around the same time, John Hall, who founded J & E Hall Limited, asked Trevithick to work on an engine for a new ship. Trevithick earned £1200 for this work. He stayed at The Bull hotel in Dartford, Kent.

Death and Memorials

After working in Dartford for about a year, Trevithick became ill with pneumonia. He died on April 22, 1833, at the Bull Hotel. He had no money, and no family or friends were with him when he died. His colleagues at Hall's works collected money for his funeral. They also paid a night watchman to guard his grave because body snatching was common then.

Trevithick was buried in an unmarked grave in St Edmund's Burial Ground, Dartford. The burial ground closed in 1857. A plaque now marks the approximate spot where he is believed to be buried.

Remembering Richard Trevithick

In Camborne, Cornwall, there is a statue of Trevithick holding one of his models. It was unveiled in 1932. On March 17, 2007, a Blue plaque was placed at the Royal Victoria and Bull hotel in Dartford. This plaque marks where Trevithick spent his last years and where he died.

The Engineering, Computer Science, and Physics departments at Cardiff University are in the Trevithick Building, which also has the Trevithick Library. In London, on the wall of the University College London building, a plaque states that Trevithick ran the first steam locomotive to carry passengers near that spot in 1808.

One of the oldest pictures of Saint Piran's Flag is in a stained glass window at Westminster Abbey, from 1888. It honors Richard Trevithick. The head of St Piran in the window looks like Trevithick himself, and the figure carries the flag of Cornwall.

There is a plaque and memorial in Abercynon. It says that Trevithick's first steam locomotive successfully pulled iron and passengers from Merthyr to that spot on February 21, 1804. There is also a building in Abercynon called Ty Trevithick (Trevithick House).

On Penydarren Road in Merthyr Tydfil, there is a memorial on the site of the Penydarren Tramway. It says that Richard Trevithick, the pioneer of high-pressure steam, built the first steam locomotive to run on rails.

A replica of Trevithick's first full-size steam road locomotive was first shown at Camborne Trevithick Day in 2001. This day celebrates Trevithick's public demonstration of high-pressure steam. The Puffing Devil replica has led the parade of steam engines at every Trevithick Day since then.

Trevithick Drive in Temple Hill, Dartford, is also named after him.

Trevithick's Lasting Impact

The Trevithick Society is named in honor of Richard Trevithick. They publish newsletters and books about Cornish engines, mining, and engineers. There is also a street named after him in Merthyr Tydfil.

Richard Trevithick is celebrated in Camborne, Cornwall, on Trevithick Day. This festival happens every year on the last Saturday in April. Steam engines from all over the UK attend. They parade through the streets of Camborne and pass by Trevithick's statue.

Richard Trevithick set the railway age in motion. He proved that high-pressure steam engines were the future, moving beyond older low-pressure engines. Later, George and Robert Stephenson built on Trevithick's ideas to create successful locomotives and railways. Trevithick truly laid the groundwork for the modern railway.

See also

In Spanish: Richard Trevithick para niños

In Spanish: Richard Trevithick para niños

- List of topics related to Cornwall

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |