Matthew Murray facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Matthew Murray

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 1765 Newcastle upon Tyne, England

|

| Died | (aged 60) |

| Resting place | Holbeck, Leeds, England |

| Occupation | Engineer Millwright Machine tool builder Entrepreneur Manager |

| Known for | Steam engines Locomotives Machine tools Textile machinery |

|

Notable work

|

Round Foundry Hypocycloidal engine Salamanca locomotive 2-cylinder marine engine Hydraulic press |

Matthew Murray (born 1765 – died 1826) was a brilliant English engineer. He designed and built amazing machines, including the first steam locomotive that was actually used for business. This locomotive was called Salamanca and had two cylinders.

Murray was always coming up with new ideas. He made big improvements to steam engines, machine tools (machines that make other machines), and equipment for the textile industry (which makes cloth).

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

Early Life

We don't know much about Matthew Murray's early years. He was born in Newcastle upon Tyne, England, in 1765.

He left school when he was fourteen. Then, he became an apprentice to learn a trade, possibly as a blacksmith (who works with iron) or a whitesmith (who works with tin or other light metals).

In 1785, after finishing his training, he married Mary Thompson. The next year, he moved to Stockton. He started working as a mechanic at a flax mill in Darlington. A flax mill is where flax (a plant fiber) is spun into thread.

Matthew and Mary had three daughters and a son, who was also named Matthew.

Moving to Leeds

In 1789, there wasn't enough work at the flax mills in Darlington. So, Murray and his family moved to Leeds. He began working for John Marshall, who became a very important flax manufacturer.

Marshall had a small mill where he wanted to improve a flax-spinning machine. Matthew Murray helped him with this. After some tries, they made the machine much better. It solved the problem of flax thread breaking during spinning.

Because of these improvements, John Marshall built a new mill in Holbeck in 1791. Murray was in charge of setting up all the new machines. He even designed some of the new flax-spinning machines himself and got a patent for them in 1790. A patent protects an invention so others can't copy it without permission.

In 1793, Murray got another patent. This one was for machines that could spin fibers. It included a machine that prepared flax, and a new way of "wet spinning" flax. This new method made the flax trade much better! Murray kept improving Marshall's machines, and his boss was very happy. It seemed Murray was the main engineer at the mill.

Starting a Business: Fenton, Murray and Wood

The Leeds area was growing fast, and there was a need for general engineers and people who could build mills. So, in 1795, Murray teamed up with David Wood. They started their own factory at Mill Green, Holbeck. Their company made machines for the many mills nearby.

Their business was so successful that in 1797, they moved to a bigger place at Water Lane. Two new partners joined them: James Fenton and William Lister. The company became known as Fenton, Murray and Wood.

Matthew Murray was the creative inventor and found new projects. David Wood managed the daily work. James Fenton handled the money.

Building Steam Engines

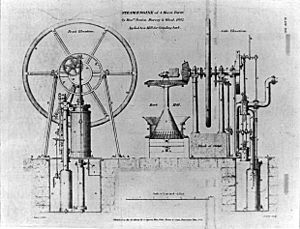

Even though the company still worked with the textile industry, Murray started thinking about how to make steam engines better. He wanted them to be simpler, lighter, and smaller. He also wanted them to be complete units that could be easily put together. Older engines often had problems because they weren't built precisely.

One challenge Murray faced was that another inventor, James Pickard, had a patent for using a crank and flywheel to turn straight motion into circular motion. Murray found a clever way around this! He used a special system called a Tusi couple hypocycloidal straight line mechanism.

This system used a large fixed ring with teeth on the inside. A smaller gear wheel, half the size of the ring, rolled inside it. The steam engine's piston rod was attached to this gear. As the piston moved back and forth in a straight line, the gear wheel turned this motion into a circle. This allowed Murray to build engines that were smaller and lighter. Once Pickard's patent ran out, Murray stopped using this complex system.

In 1799, William Murdoch invented a new type of steam valve. Matthew Murray improved these valves by connecting them to an eccentric gear on the engine's spinning shaft. This made them work even better.

Murray also invented an automatic damper. This device controlled the furnace fire based on the boiler's steam pressure. He also designed a mechanical hopper that automatically fed fuel to the fire. Murray was the first to place the piston in a horizontal (sideways) position in his steam engines.

He expected very high quality from his workers. Because of this, Fenton, Murray and Wood made machines with amazing precision. He even designed a special planing machine just for making the surfaces of the slide valves perfectly flat. This special machine was kept in a locked room, and only a few trusted workers could use it.

Today, the Murray Hypocycloidal Engine at the Thinktank museum in Birmingham, England, is the third-oldest working engine in the world. It's also the oldest working engine that uses Murray's special hypocycloidal mechanism.

The Round Foundry

Because his steam engines were so good, sales went way up! Murray needed a new place to put them together. He designed a huge, three-story circular building himself. It was called the Round Foundry. This building had a steam engine in the middle that powered all the machines inside.

Murray also built a house next to the factory. It was very modern for its time because every room was heated by steam pipes! People in the area called it "Steam Hall."

Rivalry with Boulton and Watt

The success of Fenton, Murray and Wood made their competitors, Boulton and Watt, quite unhappy. Boulton and Watt were a very famous engineering company.

They sent two of their employees to visit Murray. They pretended it was a friendly visit, but they were actually trying to spy on his production methods. Murray, perhaps too trusting, welcomed them and showed them everything. When the spies returned, they told their bosses that Murray's casting and forging work was much better than their own. Boulton and Watt then tried to copy many of Murray's methods. They even tried to bribe one of Murray's employees for information!

Finally, James Watt Jr. (the son of the famous James Watt) bought land right next to Murray's workshop. He did this to try and stop Murray's company from expanding.

Boulton and Watt also successfully challenged two of Murray's patents. Murray's patent from 1801 (for improved air pumps) and his 1802 patent (for a compact engine) were both cancelled. Murray had made a mistake by putting too many different improvements into one patent. This meant if even one small part of the patent was found to copy someone else's idea, the whole patent would be invalid.

Despite all these challenges, Fenton, Murray and Wood became serious rivals to Boulton and Watt. They received many orders for their excellent machines.

The Middleton Railway

In 1812, Murray's company built the first steam locomotive with two cylinders for John Blenkinsop. Blenkinsop managed the Middleton Colliery (a coal mine) near Leeds. This locomotive, called Salamanca, was the first steam locomotive that was successful in business.

The double cylinder was Murray's own invention. He paid Richard Trevithick a fee to use Trevithick's high-pressure steam system. But Murray improved it by using two cylinders instead of one, which made the engine run more smoothly.

At that time, cast iron rails could break easily. So, locomotives had to be very light, which limited how much they could pull. In 1811, John Blenkinsop patented a system using a toothed wheel and a special toothed rail. The locomotive's toothed wheel would grip the toothed rail on the side of the track. This was the first rack railway system.

Once stronger malleable iron rails were invented around 1819, this rack and pinion system wasn't needed anymore, except for later use on mountain railways. But until then, it allowed a small, light locomotive to pull loads that were at least 20 times its own weight!

Salamanca was so successful that Murray built three more like it. One was called Lord Wellington. The others might have been named Prince Regent and Marquis Wellington, but we don't have clear records of those names. The third locomotive meant for Middleton was sent to a coal mine near Newcastle upon Tyne. It was known as Willington there. George Stephenson saw it and used it as a model for his own locomotive, Blücher. However, Stephenson's engine didn't have the rack drive, so it wasn't as effective.

After two of these locomotives exploded, killing their drivers, and the other two became unreliable after many years, the Middleton coal mine eventually went back to using horses in 1835. It's said that one locomotive was kept for a while, but it was eventually scrapped.

Marine Engines

In 1811, Murray's company built a high-pressure steam engine for a man named John Wright. This engine was put into a paddle steamer called l'Actif, which sailed out of Yarmouth. This ship was a captured privateer (a private ship allowed to attack enemy ships) that had been bought from the government. Paddle wheels were added and powered by Murray's new engine. The ship was renamed Experiment, and the engine worked very well. It was later moved to another boat called The Courier.

In 1816, Francis B. Ogden, the United States Consul in Liverpool, received two large, twin-cylinder marine (boat) steam engines from Murray's company. Ogden then patented the design as his own in America. It was widely copied there and used to power the famous Mississippi paddle steamers.

Textile Innovations

Murray made important improvements to machines that prepared and spun flax. Preparing flax, called heckling, involves splitting and straightening the flax fibers. Murray's heckling machine won him a gold medal from the Royal Society of Arts in 1809.

When Murray made these inventions, the flax trade was struggling. Spinners couldn't make enough money. His inventions lowered the cost of making flax yarn and made the quality better. This helped the British linen trade become strong. Making flax machinery became a big business in Leeds, with many machines made for use at home and for export. This created jobs for many skilled mechanics.

Hydraulic Presses

In 1814, Murray patented a hydraulic press for baling cloth. This press was special because its top and bottom parts moved towards each other at the same time. He improved on the hydraulic presses invented by Joseph Bramah.

In 1825, Murray designed a huge press for testing chain cables. This press, built for the Navy Board, was 34 feet long. It could push with a force of 1,000 tons! The press was finished just before Murray passed away.

Death

Matthew Murray died on February 20, 1826, when he was 60 years old. He was buried in St Matthew's Churchyard in Holbeck, Leeds. His tomb has a cast iron monument on top, which was made at his own Round Foundry.

His company continued until 1843. Many important engineers learned their skills there, including Benjamin Hick, Charles Todd, David Joy, and Richard Peacock.

It shows how well Murray designed and built his steam engines that several of his large mill engines worked for over eighty years. One of them, which was installed second-hand at a locomotive repair shop in King's Cross, ran for more than a century!

Murray's only son, also named Matthew (born around 1793), trained at the Round Foundry. He later went to Russia and started his own engineering business in Moscow. He died there at age 42.

Images for kids

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |