Killingworth locomotives facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

| Power type | Steam |

|---|---|

| Builder | George Stephenson |

| Build date | 1814 |

| Gauge | 4 ft 8 in (1,422 mm) |

| Locomotive weight | 6 long tons (6.1 t) |

| Boiler | 2 ft 10 in (864 mm) dia × 8 ft 0 in (2,438 mm) long |

| Cylinder size | 8 in × 24 in (203 mm × 610 mm) |

| Locomotive brakes | ? |

| Train brakes | None |

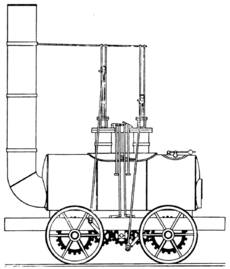

George Stephenson was a famous engineer. He built many experimental steam locomotives. These early trains worked at the Killingworth Colliery coal mine. He built them between 1814 and 1826. These locomotives helped move coal. They also laid the groundwork for modern railways.

Contents

The Start of Steam Engines

George Stephenson became the main engineer at Killingworth Colliery in 1812. He quickly made improvements. He made it easier to move coal from the mine. He used powerful fixed engines for this.

Stephenson was very interested in new ideas. He studied engines built by John Blenkinsop in Leeds. He also looked at experiments by Christopher Blackett at Wylam colliery. This was the mine where Stephenson was born.

By 1814, he convinced the mine owners to pay for a "travelling engine." This was a moving steam engine. It ran for the first time on July 25th. Stephenson discovered something important. The wheels of the engine had enough grip on the iron railway. They did not need special gears. But he still used a gear system to power the wheels.

Meet Blücher

Blücher was built by George Stephenson in 1814. It was the first of many locomotives he designed. He built them between 1814 and 1816. These engines made him famous as an engine designer. They also helped create the railway system we know today.

Blücher could pull a train weighing 30 long tons (30 t). It moved at 4 miles per hour (6.4 km/h) up a gentle slope. The engine was named after a Prussian general. His name was Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher. He helped defeat Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Stephenson carefully checked how Blücher performed. He realized it didn't save much money compared to using horses. This was true even though horse feed was very expensive. He made a big improvement. He sent the steam from the cylinders into the smokestack. This made the boiler work much better. It also reduced the annoying steam.

A science magazine called Annals of Philosophy wrote about Blücher. It said the engine saved the cost of 14 horses. Blücher itself no longer exists. Stephenson used its parts to build newer, better engines.

Improvements in 1815

By February 28, 1815, Stephenson had made many improvements. He filed a patent with Ralph Dodds. Dodds was the mine's overseer. The patent described a direct connection. This connection was between the cylinders and the wheels. It used a special ball and socket joint. The driving wheels were first connected by chains. But these chains were later replaced. Direct connections were found to be better. A new locomotive was built using these new ideas.

Wellington and Better Tracks

The first two engines showed a big problem. The railway tracks were not very good. Also, the engines had no cushioning. The tracks were often laid carelessly. The rails were only 3 feet (91 cm) long. This caused trains to often go off the tracks.

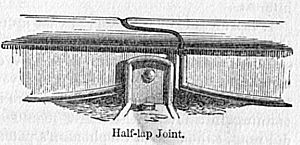

Stephenson came up with new ideas for the tracks. He designed a new support for the rails. He also used special half-lap joints between the rails. This was better than just butting them together. He replaced cast iron wheels with stronger wrought iron ones. He also used steam pressure from the boiler. This created a "steam spring" suspension for the engine. These improvements were part of a patent. He filed it with William Losh in Newcastle on September 30, 1816.

In 1818, Stephenson worked with Nicholas Wood. Wood was the head viewer at the mine. They carefully measured friction and the effects of slopes. They used a special tool called a dynamometer. These measurements helped Stephenson greatly. They were very useful for future railway developments.

Engines built with these improvements were used for a long time. They worked as locomotives until 1841. Some were even used as stationary engines until 1856. Two of these engines were named Wellington and My Lord.

Killingworth Billy

The Killingworth Billy, or just Billy, was built to Stephenson's design. It was made by Robert Stephenson and Company. For a long time, people thought it was built in 1826. But in 2018, archaeologists found new information. They discovered it was built ten years earlier, in 1816. This makes Billy the third-oldest surviving locomotive. It is also the oldest standard gauge locomotive.

Billy ran on the Killingworth Railway until 1881. Then, it was given to the city of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. For 15 years, the locomotive sat on a platform. It was near the High Level Bridge in Newcastle. Later, it moved to Newcastle Central Station. It stayed there until 1945. Then, it moved to the Museum of Science and Industry. This museum is in Exhibition Park. Today, Billy is kept safe at the Stephenson Steam Railway Museum. This museum is in North Tyneside.

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |