Matthew Boulton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Matthew Boulton

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Carl Frederik von Breda, 1792

|

|

| Born | 3 September 1728 Birmingham, England

|

| Died | 17 August 1809 (aged 80) Birmingham, England

|

| Occupation | Businessman, inventor, mechanical engineer, silversmith |

| Spouse(s) |

Mary Robinson

(m. 1749; died 1759)Anne Robinson

(m. 1760) |

| Children | 5, including Anne and Matthew |

| Relatives | Matthew Piers Watt Boulton (grandson) |

| Awards |

|

Matthew Boulton (3 September 1728 – 17 August 1809) was a clever English businessman, inventor, and engineer. He was also a skilled silversmith. He is best known for his partnership with the Scottish engineer James Watt. Together, they built and installed hundreds of advanced steam engines. These engines were a huge step forward, helping factories and mills to use machines for work. Boulton also improved how coins were made. He produced millions of coins for Britain and other countries. He even supplied the Royal Mint with modern equipment.

Born in Birmingham, Matthew Boulton took over his father's metal products business at age 31. He made the business much bigger by moving everything to the Soho Manufactory, a large factory he built near Birmingham. At Soho, he used the newest methods to create silver items, gilded bronze (called ormolu), and other beautiful decorations. He teamed up with James Watt after Watt's business partner couldn't pay a debt to Boulton. Boulton accepted a share of Watt's patent instead. He then convinced Parliament to extend Watt's patent for 17 more years. This allowed their company, Boulton & Watt, to sell many Watt's steam engines. These engines were first used in mines and then in factories across Britain and other countries.

Boulton was an important member of the Lunar Society. This was a group of smart people from the Birmingham area who were interested in arts, science, and religion. Other members included James Watt, Erasmus Darwin, Josiah Wedgwood, and Joseph Priestley. They met every month when the moon was full, which made it easier to travel home. Many people believe the Lunar Society helped create new ideas and methods in science, farming, manufacturing, and transport. These ideas helped start the Industrial Revolution.

Boulton also started the Soho Mint, where he used steam power to make coins. He wanted to fix Britain's poor quality coins. After years of effort, he got a contract in 1797 to make the first British copper coins in 25 years. His "cartwheel" coins were well-designed and hard to copy. They included the first large copper British penny, which was made until 1971. He retired in 1800 but kept running his mint. He passed away in 1809. Today, his picture is on the Bank of England's £50 note with James Watt.

Contents

What Was Birmingham Like?

Birmingham had been a center for making iron for a long time. In the early 1700s, the town grew quickly. Making iron became easier and cheaper when people started using coke instead of charcoal in 1709. England was running out of wood, but there was a lot of coal in Birmingham's area, Warwickshire, and nearby Staffordshire. This helped the change happen faster.

Much of the iron was shaped in small workshops near Birmingham. Thin iron sheets were then sent to factories in and around the town. Since Birmingham was far from the sea and big rivers, and canals weren't built yet, metalworkers focused on making small, valuable items. These included buttons and buckles. A French visitor once said that while he saw nice metal objects in Milan, "the same can be had cheaper and better in Birmingham." These small items were called "toys," and the people who made them were called "toymakers."

Matthew Boulton's family came from around Lichfield. His father, also named Matthew, moved to Birmingham and became a toymaker. He had a small workshop that specialized in buckles. Matthew Boulton was born in 1728. He was the third child, but the first Matthew had died young.

Matthew Boulton's Early Life

Matthew Boulton's father's business did well after young Matthew was born. The family moved to a nicer part of Birmingham called Snow Hill. Since the local school wasn't in good shape, Boulton went to a different school in Deritend. He left school at 15. By age 17, he had invented a way to put enamels into buckles. These buckles were so popular that they were sent to France, then brought back to Britain and sold as the newest French fashion!

On March 3, 1749, Boulton married Mary Robinson, a distant cousin. She was the daughter of a successful fabric merchant and had her own money. They lived in Lichfield for a short time, then moved to Birmingham. There, Matthew's father made him a business partner when he was 21. Even though Matthew signed letters "from father and self," he was mostly running the business by the mid-1750s. His father retired in 1757 and died in 1759.

The Boultons had three daughters, but they all died as babies. Mary Boulton became ill and passed away in August 1759. Soon after, Boulton started to like Mary's sister, Anne. Marrying a deceased wife's sister was against church rules at the time, but it was allowed by common law. They got married on June 25, 1760. Anne's brother, Luke, was against the marriage. He worried that Boulton would control their family's money. However, Luke Robinson died in 1764, and his money went to Anne, which meant Matthew Boulton gained control of it.

Matthew and Anne Boulton had two children: Matthew Robinson Boulton and Anne Boulton. Matthew Robinson Boulton later had six children. His oldest son, Matthew Piers Watt Boulton, was also a scientist. He became famous for inventing the aileron, an important part of an airplane's wing that helps it steer.

Matthew Boulton: An Innovator

Growing the Business

After his father died in 1759, Matthew Boulton took full control of the family's "toymaking" business. He spent a lot of time in London and other places, showing off his products. He even arranged for a friend to give a sword to Prince Edward. The Prince's older brother, George, Prince of Wales (who later became King George III), liked it so much that he ordered one for himself.

With money from his two marriages and his father's inheritance, Boulton looked for a bigger place to expand his business. In 1761, he rented 13 acres (about 5 hectares) at Soho. This land was in Staffordshire and included a house, Soho House, and a rolling mill. Boulton and his family later lived in Soho House. Both Matthew and Anne Boulton died there.

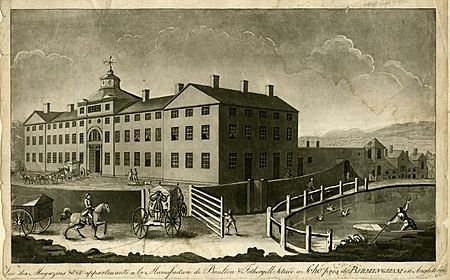

By 1765, his Soho Manufactory was built. The main building had a grand front and 19 bays for loading and unloading goods. It also had offices for clerks and managers. The building was designed by an architect named William Wyatt. Other buildings held workshops. Boulton and his partner, John Fothergill, invested in the most advanced metalworking equipment. The whole complex was seen as a modern industrial wonder. The main building alone cost five times more than expected. The partners spent over £20,000 (a huge amount back then) to build and equip the factory. They had to borrow a lot of money to pay for it.

Boulton wanted to make sterling silver items for rich people and Sheffield plate (silver-plated copper) for those with less money. Boulton and his father had made small silver items before. But Boulton was the first in Birmingham to make large silver items. To make things like candlesticks cheaper than London competitors, his company made many items from thin, shaped pieces of metal that were joined together.

One problem for Boulton was that Birmingham didn't have an assay office. This is where silver items are tested for purity and stamped with a hallmark. Small silver items didn't need testing, but larger silver plates did. They had to be sent over 70 miles (110 km) to Chester or to London. This risked damage, loss, or even having his designs copied. Boulton asked Parliament to open an assay office in Birmingham. Even though London silversmiths strongly opposed it, he succeeded. Assay offices were set up in Birmingham and Sheffield. The silver business didn't make much profit for Boulton because a lot of money was tied up in silver stock. However, his company continued to make a lot of Sheffield plate.

Boulton also started selling vases decorated with ormolu, which was a French specialty. Ormolu was gold mixed with mercury, applied to an item, and then heated to leave a gold decoration. In the late 1760s and early 1770s, rich people loved decorated vases. Boulton first ordered ceramic vases from his friend Josiah Wedgwood, but the ceramic wasn't strong enough. So, Boulton chose marble and other decorative stones for his vases. He copied designs from ancient Greek art and borrowed artworks from collectors.

In March 1770, Boulton visited the Royal Family and sold several vases to Queen Charlotte, King George III's wife. He held yearly sales at Christie's in 1771 and 1772. These sales made Boulton and his products famous, but they didn't make much money. Many items didn't sell or sold for less than they cost. When the vase trend ended, Boulton's company had many unsold vases. They sold most of them in one big sale to Catherine the Great of Russia. She said the vases were better and cheaper than French ones.

One of Boulton's most successful products was the metal mounts for small Wedgwood items. These included plaques, cameo brooches, and buttons made from Wedgwood's special ceramics, like jasper ware. The mounts were made of ormolu or cut steel, which looked like jewels. Boulton and Wedgwood were friends. Wedgwood once wrote that Boulton was the "first Manufacturer in England" and that he liked Boulton's spirit.

In the 1770s, Boulton started an insurance system for his workers. This was a model for later plans. It gave workers money if they were injured or sick. It was the first of its kind in a large factory. Employees paid a small part of their wages into the Soho Friendly Society, and joining was required. The company's apprentices were poor or orphaned boys who could be trained as skilled workers. Boulton didn't hire sons of rich people as apprentices, saying they wouldn't fit in with the poorer boys.

Not all of Boulton's new ideas worked out. He tried to mechanically reproduce paintings for middle-class homes but eventually stopped. He also made an alloy called "Eldorado metal" that he claimed wouldn't rust in water. He thought it could be used to cover wooden ships. But after tests, the Admiralty (the navy) said it didn't work.

- Products of Boulton's manufactory

Working with James Watt

Boulton's Soho factory didn't have enough water power, especially in summer when the millstream was low. He realized that a steam engine could help. It could either pump water back to the millpond or power equipment directly. He started writing to James Watt in 1766 and met him two years later. In 1769, Watt patented an engine with a new part called a separate condenser. This made his engine much more efficient than older ones. Boulton saw that this engine could power his factory and also be a profitable business.

After getting the patent, Watt didn't do much to develop the engine. In 1772, Watt's partner, Dr. John Roebuck, had money problems. He owed Boulton £1,200. Boulton accepted Roebuck's two-thirds share in Watt's patent to settle the debt. Boulton's own partner, Fothergill, didn't want to be part of this risky deal.

At that time, steam engines were mainly used to pump water out of mines. The common engine was the Newcomen steam engine. It used a lot of coal and couldn't keep deeper mines clear of water. Watt's work was known, and some mines waited to buy engines, hoping Watt would soon sell his invention.

Boulton praised Watt's skills, which led to a job offer from the Russian government. Boulton had to convince Watt to turn it down. In 1774, Boulton convinced Watt to move to Birmingham, and they became partners in 1775. By then, six of Watt's original 14-year patent had passed. But thanks to Boulton's efforts, Parliament passed a law extending Watt's patent until 1800. Boulton and Watt started working to improve the engine. With help from iron master John Wilkinson, they made the engine ready for sale.

In 1776, the partnership built two engines: one for Wilkinson and one for a mine in Tipton. Both worked well, bringing good publicity. Boulton and Watt then started installing engines in other places. The company usually didn't make the engine itself. Instead, the buyer bought parts from different suppliers. Then, a Soho engineer would assemble the engine on site. The company made money by charging one-third of the coal savings each year for 25 years. This meant their engine used less coal than older ones, and they got a share of the money saved.

The county of Cornwall was a big market for their engines because it had many mines. However, there were problems there, like local rivalries and high coal prices. This meant Watt, and later Boulton, had to spend several months a year in Cornwall. They oversaw installations and solved problems with mine owners. In 1779, the company hired engineer William Murdoch. He took over most of the on-site work, allowing Watt and Boulton to stay in Birmingham.

The pumping engine for mines was a great success. In 1782, the company wanted to change Watt's engine to have a spinning motion. This would make it useful for mills and factories. Boulton wrote to Watt, urging him to modify the engine. He said they were reaching the limits of the pumping engine market. Watt spent much of 1782 on this project and finished it by the end of the year. Orders soon came in from mills and breweries. King George III visited the Whitbread brewery in London and was impressed by their engine. Boulton used two engines to grind wheat at his new Albion Mill in London. This mill ground 150 bushels of wheat per hour! The mill wasn't a financial success, but it was great advertising for the company's new engine. Before it burned down in 1791, the mill's fame spread widely, and orders for spinning engines came from Britain, the United States, and the West Indies.

Between 1775 and 1800, the company made about 450 engines. They didn't let other companies make engines with separate condensers. During that time, about 1,000 Newcomen engines (which were less efficient but cheaper) were made in Britain. Boulton once told a visitor, "I sell here, sir, what all the world desires to have—POWER." The invention of an efficient steam engine allowed large industries to grow and made big industrial cities possible.

Making Coins

By 1786, two-thirds of the coins in Britain were fake. The Royal Mint (the official coin maker) even shut down, making things worse. Few silver coins were real. Even copper coins were melted down and replaced with light, fake ones. The Royal Mint didn't make any copper coins for 48 years, from 1773 to 1821. This gap was filled by copper tokens made by merchants. Boulton made millions of these merchant tokens. When the Royal Mint did make coins, they were often poorly made.

Boulton became interested in coinage in the mid-1780s. Coins were just another small metal product, like the ones he already made. He also owned shares in copper mines and had a lot of copper himself. However, when people asked him to make fake money, he refused. In 1788, he set up the Soho Mint as part of his factory. The mint had eight steam-powered presses. Each press could make between 70 and 84 coins per minute.

Boulton's company had trouble getting a contract to make British coins at first. But they soon started making coins for the British East India Company to use in India. The coin crisis in Britain continued. Boulton offered to make new coins for less than half the cost of what the Royal Mint usually charged. He wrote to his friend, Sir Joseph Banks, describing how good his coin presses were.

Boulton spent a lot of time in London trying to get a contract to make British coins. But in June 1790, the government put off the decision. Meanwhile, the Soho Mint made coins for the East India Company, the Sierra Leone Company, and Russia. They also made high-quality blank coins for other countries' mints. The company sent over 20 million blanks to Philadelphia for the United States Mint to turn into cents and half-cents. The US Mint Director said they were "perfect and beautifully polished." The high-tech Soho Mint became famous, and rivals even tried to spy on it or get it shut down.

Britain's money problems got very bad in February 1797. The Bank of England stopped exchanging its paper money for gold. To get more money circulating, the government decided to issue many copper coins. Lord Hawkesbury called Boulton to London on March 3, 1797, and told him the government's plan. Four days later, Boulton met with the Privy Council and got a contract at the end of the month.

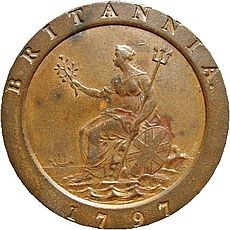

On July 26, 1797, King George III announced that new copper coins would be made for "the payment of the laborious poor." These coins would be worth one penny and two pennies. The proclamation said the coins must weigh one and two ounces respectively. This made the value of the metal in the coin almost equal to its face value. Boulton worked hard to make it difficult for counterfeiters (people who make fake money). The coins were designed by Conrad Heinrich Küchler. They had a raised rim with sunken letters and numbers, which were hard for fakers to copy. The two-penny coins were exactly an inch and a half across. Sixteen pennies lined up would reach two feet. These exact measurements and weights made it easy to spot fake, lightweight coins. The coins were nicknamed "cartwheels" because the two-penny coin was so big and both had wide rims. The penny was the first copper coin of its kind.

The cartwheel two-penny coin was not made again. Much of it was melted down in 1800 when copper prices went up. It was also too heavy for everyday use and hard to make. To Boulton's dismay, the new coins were being faked with copper-covered lead within a month of being issued. Boulton received more contracts in 1799 and 1806 for the smaller copper coins. He greatly reduced the counterfeiting problem by adding lines to the coin edges and making the blanks slightly curved. Counterfeiters then focused on older, easier-to-fake coins.

Matthew Boulton's Interests

Science and the Lunar Society

Boulton never had formal science training. His friend and fellow Lunar Society member James Keir said after Boulton's death that he had a "strong desire for knowledge" and a "quick understanding."

From a young age, Boulton was interested in new scientific discoveries. He didn't believe that electricity was a part of the human soul, writing that "we know 'tis matter & 'tis wrong to call it Spirit." His interest led him to meet other science fans, like John Whitehurst. In 1758, the American printer Benjamin Franklin, who was a leading expert in electricity, visited Birmingham. Boulton met him and introduced him to his friends. Boulton worked with Franklin to try and store electricity in a Leyden jar.

Even though he was busy expanding his business, Boulton continued his "philosophical" work (which is what scientific experiments were called then). He wrote notes on things like how mercury freezes and boils, people's pulse rates at different ages, and how to make sealing wax. However, Erasmus Darwin, another friend and Lunar Society member, joked to him in 1763, "As you are now become a sober plodding Man of Business, I scarcely dare trouble you to do me a favour in the... philosophical way."

The science enthusiasts in Birmingham, including Boulton, Whitehurst, Keir, Darwin, Watt, potter Josiah Wedgwood, and chemist Joseph Priestley, started meeting informally in the late 1750s. These meetings grew into monthly gatherings near the full moon. The full moon provided light for them to travel home afterward. The group eventually called itself the "Lunar Society." After a member named Dr. William Small died in 1775, Boulton helped make the Society more formal. They met on Sundays, starting with dinner at 2 p.m. and discussing ideas until at least 8 p.m.

Sir Joseph Banks was also involved with the Lunar Society, though not a formal member. In 1768, Banks sailed with Captain James Cook to the South Pacific. He took green glass earrings made at Soho to give to the native people. In 1776, Captain Cook ordered an instrument from Boulton, probably for navigation. Boulton warned Cook that it might take years to finish. Cook left on his voyage in June 1776 and was killed almost three years later. Boulton's records don't mention the instrument again.

Besides scientific discussions, Boulton also had business dealings with some members. Watt and Boulton were partners for 25 years. Boulton bought vases from Wedgwood's pottery to decorate with ormolu. Keir was a long-time supplier and friend of Boulton.

In 1785, both Boulton and Watt were elected as Fellows of the Royal Society. This was a great honor for their scientific contributions.

Even though Boulton hoped the Lunar Society would last, its members were not replaced as they died or moved away. In 1813, four years after Boulton's death, the Society ended. Since there were no official meeting notes, few details of their gatherings remain. However, historians believe the Society had a lasting impact, helping to develop new ideas that shaped the Industrial Revolution.

Helping the Community

Boulton was very involved in community activities in Birmingham. His friend Dr. John Ash wanted to build a hospital in the town. Boulton, who loved the music of Handel, thought of holding a music festival in Birmingham to raise money for the hospital. The first festival took place in September 1768. This was the start of a series of festivals that lasted until 1912. The hospital, Birmingham General, opened in 1779. Boulton also helped build the General Dispensary, where people could get outpatient treatment. He was a strong supporter of the Dispensary, serving as treasurer. He once wrote, "If the funds of the institution are not sufficient for its support, I will make up the deficiency." The Dispensary soon needed a bigger building, and a new one opened in 1808, shortly before Boulton died.

Boulton helped start the New Street Theatre in 1774. He later wrote that having a theater encouraged wealthy visitors to come to Birmingham and spend more money. Boulton tried to get the theater recognized as a "patent theatre," which meant it could put on serious plays. He failed in 1779 but succeeded in 1807. He also supported Birmingham's Oratorio Choral Society and helped organize private concerts in 1799. He had a reserved seat at St Paul's Church, Birmingham, which was known for its excellent music.

Before police forces were common, Boulton served on a committee to organize volunteers to patrol the streets at night and reduce crime. He supported the local militia (a group of citizens who act as soldiers), providing money for weapons. In 1794, he was elected High Sheriff of Staffordshire, which was an important local role.

Besides improving local life, Boulton was interested in world events. He first supported the American colonists who rebelled against Britain. But he changed his mind when he realized an independent America might hurt British trade. In 1775, he organized a petition urging the government to be tougher with the Americans. However, when the revolution succeeded, he continued to trade with the new United States. He was more sympathetic to the French Revolution, believing it was justified, but he was horrified by the violence. When war with France broke out, he paid for weapons for a group of volunteers ready to fight any French invasion.

Later Life, Death, and Legacy

When Boulton's wife, Anne, died in 1783, he was left to care for his two teenage children. Neither his son, Matthew Robinson Boulton, nor his daughter, Anne, were very healthy. Young Matthew was often sick and struggled in school until he joined his father's business in 1790. Anne suffered from a leg illness that limited her life. Despite his long business trips, Boulton cared deeply for his family.

When Watt's patent expired in 1800, both Boulton and Watt retired from their partnership. They each handed over their roles to their sons, who were also named Matthew and James. The sons made changes, quickly stopping public tours of the Soho Manufactory, which the elder Boulton had been proud of. In retirement, Boulton stayed active, continuing to run the Soho Mint. When a new Royal Mint was built in London in 1805, Boulton won the contract to equip it with modern machinery. His continued work worried Watt, who had fully retired.

Boulton helped deal with a shortage of silver coins. He convinced the government to let him restrike a large number of Spanish dollars (foreign coins) that the Bank of England had. The Bank had tried to use these dollars by stamping a small image of King George III on them, but people didn't want to accept them, partly because of fakes. Boulton completely removed the old design when he restruck them. Even though Boulton wasn't as successful as he hoped at stopping fakes (high-quality fakes appeared within days), these coins were used until the Royal Mint made many new silver coins in 1816. He oversaw the last issue of his copper coins for Britain in 1806 and a large issue of copper coins for Ireland. Even as his health failed, he had his servants carry him from Soho House to the Soho Mint. He would sit and watch the machines, which were very busy in 1808 making almost 90 million coins for the East India Company. He wrote, "Of all the mechanical subjects I ever entered upon, there is none in which I ever engaged with so much ardour as that of bringing to perfection the art of coining."

By early 1809, he was very ill. He had suffered from kidney stones for a long time, which caused him great pain. He died at Soho House on August 17, 1809. He was buried in the graveyard of St. Mary's Church, Handsworth, in Birmingham. Later, the church was expanded over his grave. Inside the church, there is a large marble monument to him, made by the sculptor John Flaxman. It includes a marble bust of Boulton.

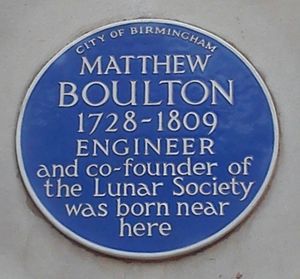

Matthew Boulton is remembered with several memorials in and around Birmingham. Soho House, his home from 1766 until his death, is now a museum. His first workshop, Sarehole Mill, is also a museum. The Soho archives are part of the Birmingham City Archives. He is recognized by blue plaques at his birthplace and at Soho House. A golden bronze statue of Boulton, Watt and Murdoch (1956) stands in central Birmingham. Matthew Boulton College was named after him in 1957. In 2009, on the 200th anniversary of his death, Birmingham City Council held a year-long festival celebrating his life and work.

On May 29, 2009, the Bank of England announced that Boulton and Watt would appear on a new £50 note. This design is the first to feature two people on a Bank of England note. It shows the two industrialists side by side with images of a steam engine and Boulton's Soho Manufactory. Quotes from each man are on the note: "I sell here, sir, what all the world desires to have—POWER" (Boulton) and "I can think of nothing else but this machine" (Watt). The notes started circulating on November 2, 2011.

In March 2009, Boulton was honored with a Royal Mail postage stamp. On October 17, 2014, a bronze memorial plaque to Boulton was unveiled in Westminster Abbey, next to a plaque for James Watt.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Matthew Boulton para niños

In Spanish: Matthew Boulton para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |